When he turned his coat, Benedict Arnold turned a revolution against him.

General George Washington got to West Point, New York, on Monday, September 25, 1780, expecting to find his subordinate, Major General Benedict Arnold, awaiting him. Washington recently had appointed Arnold commander of the fort at West Point that secured the Hudson River against British attack. Washington had told Arnold he wanted to inspect the camp, but Arnold was absent. A servant told Washington Arnold had said he would return shortly.

That was a lie.

Just before Washington arrived, Arnold had fled to the Hudson shore, where a rowboat carried him downriver to HMS Vulture, a British warship. Washington soon found out why West Point’s commander had cut and run. Captured documents revealed that Benedict Arnold had sold out his country. “Whom can we trust now?” Washington said.

Arnold’s about-face staggered the commander in chief, who had extolled the other man as his “fighting general.” The hero of Ticonderoga and Saratoga and Lake Champlain, the American Hannibal who had force-marched troops through the bitter Maine wilderness to fight in Quebec, Arnold had had his share of disputes with the Continental Congress—disputes in which Washington often took Arnold’s side. No more.

The revolution was at a critical juncture. Treason was a hanging offense; however, summarily executing Arnold could unravel the rebel cause. Washington ordered Major General Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, the whip-smart cavalryman, to choose among his dragoons “a courageous man” to track down Arnold and take him alive. Under no circumstances was the rebel operative to harm or kill the turncoat, even if that meant allowing Arnold to get away. No one should think “ruffians had been hired to assassinate him,” Washington declared to his officers.

“My aim is to make a public example of him,” Washington said. So began a lengthy, frustrating campaign to seize Benedict Arnold and make him pay for his crime.

Benedict Arnold always had a head for business and a hunger for wealth. Born in Norwich, Connecticut, he grew up in New Haven. After apprenticing there at a pharmacy, he enlisted in the colonial militia at 16, fighting in the French and Indian War. Afterward he set himself up as an apothecary and ship’s captain, prospering on rum and molasses. But British trade policies and royal taxes drove him into the arms of the rebellious Sons of Liberty and then the Continental Army.

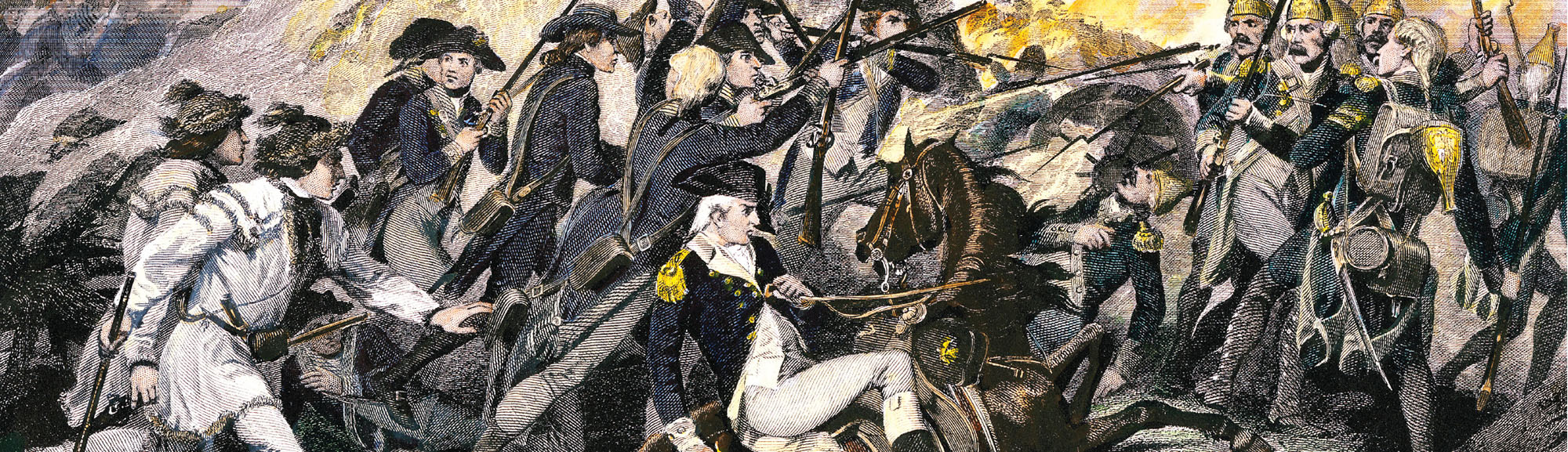

In May 1775, Arnold, along with frontiersman Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys, mounted a surprise attack on New York’s Fort Ticonderoga that took the bastion from the British. On his way back to the Continental camp at Cambridge, Massachusetts, Arnold learned that his wife, Margaret, had died, leaving him with three young sons. He left his boys in the care of his sister, Hannah, and returned to war.

Arnold loved combat and had ambition to match, even exceed, his valor. He was not a man to avoid conflict, and he got on the wrong side of Major General Horatio Gates and other key rebel commanders. Washington was planning to take Montreal, an assignment Arnold lusted after. However, the post went to Major General Richard Montgomery. Arnold suggested a second attack up north; Washington granted him a colonel’s commission to lead 1,100 troops against Quebec City. Ill-prepared, the unit left in September 1775 on a grueling 350-mile trip up Maine’s Kennebec River. Only 600 men survived. At Quebec, Arnold joined forces with Montgomery, fresh from capturing Montreal, to besiege the city. That action failed, as did a December 31 assault that ended with Montgomery dead and Arnold with a badly wounded left leg.

The Americans retreated south to Lake Champlain, where Arnold revived his seadog skills, commanding a fleet of gunboats hastily built to hold the strategic waterway against British advances. The Continental Congress named Arnold a brigadier general. In open session, Thomas Jefferson praised the Connecticut soldier.

However, along with combat and attention, Arnold also loved money. At home, cash was short, and in Congress there were mutterings that on the retreat from Quebec, Arnold had profiteered by selling the army provisions.

In February 1777, Congress declined to promote Arnold—he had hoped to make major general but Connecticut had too many of those—a decision doubtless influenced by Gates, a rival for promotion and assignments.

Affronted, Arnold proposed to resign. Washington turned down his offer, meanwhile warning Congress that “two or three other very good officers” might quit fighting if legislators kept letting politics dominate the army’s leadership. Pressing his case, Arnold petitioned Congress. The result was a plan to convene a Board of War in Philadelphia to examine the details of Arnold’s stewardship during the Champlain retreat.

Arnold was on his way to Philadelphia when he heard British troops were marching on a rebel supply depot in Danbury, Connecticut. He was too late to save the stores, but at nearby Ridgefield, he organized militiamen to cut off the British retreat. In the fight, the enemy shot Arnold’s horse, which fell and pinned him to the ground in his stirrups. A Loyalist, extending a fixed bayonet, shouted at him to surrender.

“Not yet!” Arnold replied.

Drawing pistols from his saddle, he shot and killed the soldier, freed himself, and limped off with his troops.

Exonerating Arnold, the Philadelphia board declared itself satisfied with his “character and conduct, so cruelly and groundlessly aspersed.” In May, Congress finally promoted him to major general, but refused to restore his seniority over officers who had been promoted in February. Arnold again played the resignation card, but before he could act on that threat British General John Burgoyne retook Fort Ticonderoga. Washington sent Arnold to assist Gates, a senior major general, in defending the crucial Hudson River Valley. “I would recommend him for this business,” Washington wrote. “He is active, judicious and brave. I have no doubt of his adding much to the honors he has already acquired.”

Arnold arrived to the sound of guns. On September 19, 1777, Gates and Burgoyne clashed about 10 miles south of Saratoga, New York. Arnold led a detachment that included sharpshooters under Colonel Daniel Morgan who inflicted heavy casualties on the attacking foe. Field commanders and ordinary soldiers credited their success to Arnold, but in reporting the action to Congress, Gates made no mention of Arnold. The two argued. With the battle still on, Gates relieved a furious Arnold of his command and confined him to his tent. A week later, in the Second Battle of Saratoga, Arnold left camp against orders to join his men in attacking a British redoubt.

During the fighting, a musket ball and Arnold’s collapsing horse shattered his already compromised left leg; though the injuries healed, that limb now was two inches shorter than the right.

In spring 1778, after a winter stalemate that saw the Continental Army hunker in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, while 23 miles east British troops occupied Philadelphia, the British abandoned that city and headed for New York. Needing a military governor to oversee Philadelphia, Washington in June 1778 rewarded Arnold’s heroics at Saratoga with that position. City life and Philadelphia’s vibrant social scene appealed to Arnold, who lived extravagantly. That summer, the widowed rebel general, his raffishly handsome looks set off by a ruined leg, met Margaret Shippen.

Daughter of wealthy and influential Judge Edward Shippen, a Loyalist sympathizer, Peggy Shippen was petite and fair-haired, with sparkling gray eyes. A contemporary described her as “delicately beautiful, brilliant, witty, a consummate actress and astute businesswoman.” While the British were running her hometown, she had flirted with a charming officer, John André, who left for New York. Peggy still corresponded with André, whom General Henry Clinton, British military commander in North America, had made his spymaster in April 1779.

Pretty Peggy bowled over Benedict Arnold. On April 8, 1779, they wed in a ceremony at her father’s townhouse on Fourth Street. She was two months shy of 19; he was 38.

Arnold’s taste for the high life during his tenure as Philadelphia’s military governor renewed rumors about the source of his wealth. In a newspaper, a letter writer asked, “From whence these riches flowed if you did not plunder Montreal?” A lower-level, politically connected Continental Army officer, John Brown, published a handbill savaging Arnold. “Money is this man’s God, and to get enough of it he would sacrifice his country,” the broadside claimed. Major Allan McLane, who had spied for Washington when the British held Philadelphia, also complained of Arnold’s activities. McLane believed the governor had made money selling abandoned British goods. McLane told Washington that Arnold might be in cahoots with the enemy. Washington stood by his man.

Arnold demanded a court-martial be convened that he believed would clear his name.

“Having made every sacrifice of fortune and blood, and become a cripple in the service of my country, I little expected to meet the ungrateful returns I have received from my countrymen,” he told Washington in a letter.

Repeatedly delayed, the court-martial finally acquitted Arnold of all but two minor charges, for which Congress publicly reprimanded him. In April 1780, Washington weighed in. He hailed Arnold’s “distinguished services to the Country,” but said he found Arnold’s unsavory conduct “particularly reprehensible, both in a civil and military view.”

Privately, Washington wrote to advise Arnold. “Exhibit anew those noble qualities which have placed you on the list of our most valued commanders,” Washington said. “I will furnish you, as far as it may be in my powers, with the opportunities for regaining the esteem of your country.”

Proud, put-upon, and debt-laden, Arnold started thinking about how to change his fortune for the better. A month into their marriage, he and Peggy sought to land him a British generalship. Their overture to the enemy used classic methods, including code names—Arnold was “Monk”—and invisible ink. Peggy Arnold, exploiting her friendship with André and other British officers, was the go-between—and Arnold’s energetic partner in crime, though her husband said later that his spouse was “as innocent as an angel.”

Working both sides of the war, Arnold continued to pester Washington for plum assignments, such as command of West Point, a fortress overlooking the Hudson 40 miles north of New York City. A man who had control of such a key bastion would have a very valuable chit with which to bargain.

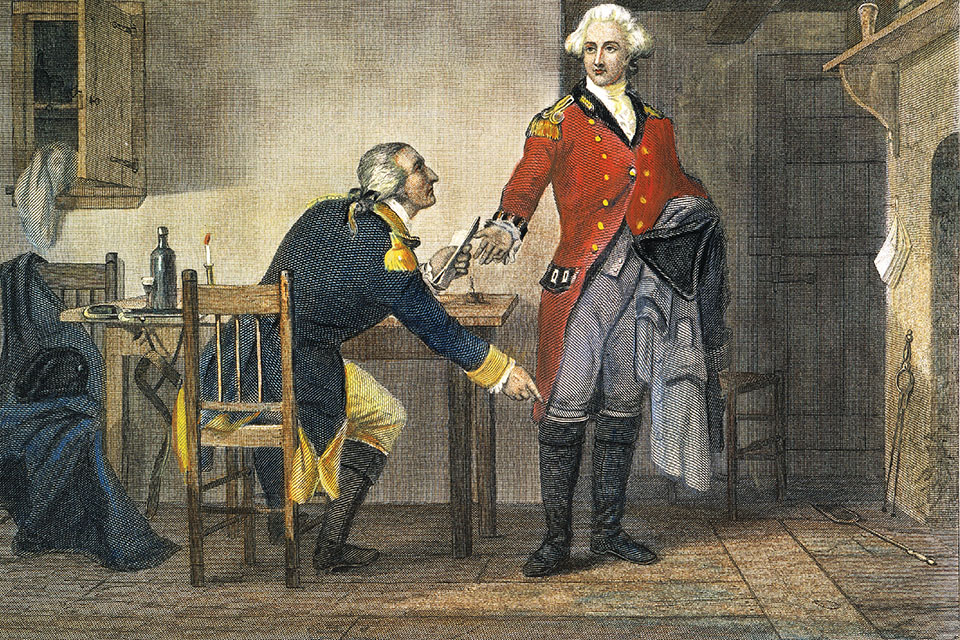

In August 1780, Washington did assign West Point to Arnold. That September, Arnold agreed to surrender the fort for a commission in the British Army and £20,000, arranging to seal the deal by meeting André face-to-face.

On Wednesday, September 20, 1780, André left Dobbs Ferry, New York, aboard sloop-of-war HMS Vulture to sail up the Hudson. A night later, Vulture anchored 13 miles downriver from West Point in Haverstraw Bay.

Coming ashore by boat, André found Arnold. The men talked nearly until dawn, during which time American troops fired on Vulture, causing the crew to hoist anchor and head south, stranding André. To help his British co-conspirator get through American lines, Arnold gave André a civilian cloak and a passport identifying him as “John Anderson.” He also gave André six sheets of paper on which he had drawn diagrams and written instructions for taking West Point.

André went across the river and made for the nearest British outpost, at Tarrytown, New York. The English spy obtained a horse and was well on his way to safety when three local patriot militiamen hailed him. Suspicious, the men searched André, finding Arnold’s papers in one of his socks.

The nearest American command post was across the river at Tappan, New York. Binding André, the militiamen marched him to the shore, stopping along the way at American outposts. At one, the ranking officer sent a messenger with the incriminating papers to Danbury, Connecticut, where Washington was said to be. The office sent another messenger to West Point to inform Arnold of André’s capture.

The messenger reached Arnold’s residence at West Point just before Washington was to arrive.

Reading the message, Arnold spoke briefly with Peggy, got on his horse, and rode off.

Washington and his companions arrived to find Peggy Arnold feigning a hysterical fit to keep the truth from the commander in chief. As she was raving, her husband was at riverside ordering six bargemen to row him south, where he found Vulture. As soon as Arnold had boarded, the crew sailed to New York, where his new masters conferred on him a brigadier general’s commission, accompanied by an annual pension.

The messages unmasking André as a spy were nearly two days reaching Washington at West Point. A Board of Officers chosen by the commanding general tried André and found him guilty of espionage. He was hanged at Tappan October 2.

Major General Nathanael Greene expressed emotions many American army officers shared toward Arnold.

“How black, how despised…loved by none, and hated by all,” Greene said of his former friend and compatriot. “Once his country’s idol, now her horror.”

Washington immediately set in motion a move to abduct Arnold and make an example of him. As ordered, Lee chose Sergeant Major John Champe, a 24-year-old Virginia dragoon “rather above the common size, full of bone and muscle,” to attempt to infiltrate the British camp in New York City, there to isolate Arnold and take him prisoner.

To accomplish that—and to dupe the British into allowing him into their midst—Champe had to fake a defection from the American camp. He and Lee agreed on a scheme to accomplish that. Lee again emphasized the need to keep the turncoat healthy. “If you find that you cannot seize [Arnold] unhurt, do not seize him at all,” he told his fellow Virginian. “To kill him would give the enemy an excuse for alleging all sorts of falsehoods against us.”

On the night of October 22, 1780, Champe rode 10 miles from his regiment at Totowa, New Jersey, to the Hudson River. American sentries, who were not informed in advance of the ruse, chased him all the way, but Champe eluded them to reach a British ship on the river. The vessel’s officers welcomed him aboard as a defector.

After interrogation by the British, who accepted him as a legitimate turncoat, Champe was sent to New York to join the American Legion, a British unit composed primarily of deserters from the Continental Army.

In New York, with two accomplices sent by Lee, Champe shadowed Arnold’s every move and soon saw an opportunity to act. He outlined his strategy in a message sent by courier to Washington. “The plan proposed for taking A—ld…has every mark of a good one,” the commander in chief wrote.

On the night of December 11, Champe loosened a section of the wooden fence enclosing Arnold’s garden, then replaced the pieces so that they appeared as always. He told one of the two helpers to bring a boat to a landing on the Hudson.

Champe planned to sneak into the traitor’s garden with his other fellow kidnapper, seize Arnold, gag him by stuffing a cloth into his mouth, and carry him to the landing, where a waiting boat would take the men and their prisoner to Lee on the New Jersey shore.

But only hours before Champe’s big moment, Arnold changed his quarters to get ready for an expedition south. Arnold’s men, including Champe, received unexpected orders to board their ships immediately.

“I was hurried on board the ship without having had time so much as to warn Lee that the whole arrangement was blown up,” Champe recalled years later.

Only after the ships were out at sea did Champe realize the force was going to invade his home state of Virginia, led by the traitor he had been sent to kidnap.

Arnold’s force of 1,600 troops captured Richmond by surprise, and then went on a rampage throughout the state. In response, Washington sent the Marquis de Lafayette to Virginia with 1,200 troops and support from a small French fleet.

Lafayette was under orders from Washington that should Arnold “fall into your hands,” he was to punish him “in the most summary way”—hang him immediately—“due to his treason and desertion.” Washington had hardened toward Arnold, perhaps because of the destruction he had wrought in Washington’s home state.

Arnold’s attacks throughout Virginia also attracted the attention of Governor Thomas Jefferson, who had his own plan to capture the traitor.

On January 31, 1781, Jefferson wrote to Brigadier General Peter Muhlenberg about a matter of “profound secrecy.” He urged Muhlenberg to hire frontiersmen for a mission, authorizing him to enlist as many men as necessary. Muhlenberg was to “reveal to them our desire, and engage them [to] undertake to seize and bring off this greatest of all traitors.” He offered 5,000 guineas to them if they brought Arnold in alive, and promised their names would “be recorded with glory in history.”

An increasingly paranoid Arnold, however, knew he was a marked man and employed handpicked soldiers and sailors as guards. Each morning, he armed himself with two small pistols in case of an emergency. Muhlenberg’s men were never able to get close to him. Arnold remained safe in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Months passed. Each morning Arnold rode along the Chesapeake shore. In March 1781, Major Allan McLane—Washington’s spy, who had suspected Arnold of treachery—plotted to grab him as he galloped. But British warships arrived, unexpectedly anchoring in the wrong place, and once again, Arnold escaped capture.

Jefferson turned to an even more desperate measure proposed by a Virginia naval captain—and British deserter—named Beesly Edgar Joel. Joel suggested turning an old navy craft into a “fire ship” to be filled with explosives and crashed into Arnold’s vessel, killing him or forcing him to abandon ship and be captured. Jefferson embraced the idea, ordering that Joel “have everything provided which he may think necessary to ensure Success.” Jefferson did not know Joel was a deserter in whom Washington placed no trust. The intended fire ship grounded on a sandbar in the James River. Arnold apparently learned of the plot, and Jefferson called it off.

After British General Charles Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781, the Arnold family sailed for England. London embraced them—at first. Peggy established a splendid home and Benedict again took up trading. But their welcome quickly cooled and Arnold’s ventures in Britain and Canada failed. Benedict died in 1801. To pay his debts, Peggy auctioned the house and its contents. She died in 1804. The lone statue to Arnold—the “Boot Monument” at Saratoga, New York—invokes the “most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army who was desperately wounded on this spot.”

No name appears.