While a number of enslaved African Americans looked on, 40-year-old Thomas Jefferson, shovel in hand, began poking into the side of the large Indian mound. Spherical in shape and 40 feet in diameter, it sat on the flood plain of the gently flowing Rivanna River, six miles north of Monticello, his mountaintop home. Jefferson was standing in a ditch surrounding the “barrow,” as he called it, when he commenced. “I first dug superficially in several parts of it,” he wrote, “and came to collections of human bones, at different depths, from six inches to three feet below the surface. These were lying in the utmost confusion….”

Americans can usually rattle off a few of Thomas Jefferson’s titles and achievements. The principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson, our third president, was the driving force behind the Louisiana Purchase and the wildly successful Meriwether Lewis and William Clark Expedition. But he was much more. Jefferson was a true Renaissance man, a brilliant polymath with an eclectic and dizzying array of interests.

Of these, he called science his “passion,” and over the course of his busy life, despite devoting more than 30 years to public service, Jefferson made contributions to botany, paleontology, meteorology, entomology, ethnology, and comparative anatomy. He was also an amateur archaeologist, and in 1783, spurred on by a document sent him by the French government, Thomas Jefferson excavated a Monacan Indian burial mound. It was one of his greatest scientific accomplishments. “In applying his innate sense of order and detail,” wrote science historian Silvio A. Bedini, “he anticipated modern archaeology’s basis and methods by almost a full century.”

Born on April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, his father’s plantation in the Virginia Piedmont—the western edge of European settlement—Thomas Jefferson studied in private schools prior to his 1760 enrollment at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Va. There, as he later wrote, it was his “great good fortune” to study under and befriend, Dr. William Small, a disciple of the Scottish Enlightenment who “probably fixed the destinies” of his life. “[F]rom his conversation,” Jefferson wrote, “I got my first views of the expansion of science & of the system of things in which we are placed.”

It was in Williamsburg, too, that young Jefferson had an encounter that helped foster his fascination with Native Americans. In the spring of 1762, a party of 165 Cherokee from the Holston River Valley accompanied their chief to Williamsburg prior to his journey to London. Called “Ontesseté,” this chieftain delivered a stirring farewell oration the evening before he departed. Enthralled, Jefferson looked on from the edge of the native’s camp. “The moon was in full splendor,” he later wrote, “and to her he seemed to address himself….His sounding voice, distinct articulation, animated action, and the solemn silence of his people…filled me with awe and veneration, although I did not understand a word he uttered.”

After college, Jefferson practiced law for seven years. Then, following service in the Virginia House of Burgesses, the Continental Congress, and the Virginia House of Delegates, he was elected governor of the Old Dominion in 1779 during the American Revolution. In October 1780, the same year he was reelected governor, Jefferson received a fascinating set of 22 queries—in essence, a questionnaire—from the secretary of the French legation to the United States, François, Marquis de Barbé-Marbois (who in 1803 would play a large role in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase). The questionnaire sought out some of the basic statistical information on the nascent American states, then embroiled in a war with France’s common enemy.

The Virginia copy had been forwarded to Jefferson by a member of the state’s congressional delegation. Query number three, for example, asked for “An exact description of [the state’s] limits and boundaries,” while seven inquired about “The number of its inhabitants.” Others sought out details on the state’s religions, rivers, mountains, flora, seaports, colleges, commercial productions, and military force, as well as customs and manners.

An inveterate compiler of data, Jefferson was well-prepared to respond. As he later noted in his Autobiography: “I had always made it a practice whenever an opportunity occurred of obtaining any information of our country [Virginia], which might be of use to me in any station public or private, to commit it to writing. These memoranda were on loose papers….I thought this a good occasion to embody their substance, which I did in the order of Mr. Marbois’ queries, so as to answer his wish and to arrange them for my own use.”

Although burdened with the responsibilities of his governorship, Jefferson began working on his reply immediately. Unfortunately, the declining state of military affairs in Virginia for Jefferson’s last seven months as governor meant that he had to set aside the project that so sparked his enthusiasm. During this tumultuous time, he was forced to flee twice from Richmond, the new state capital he had established. And—after Jefferson and the legislature relocated to Charlottesville to escape the enemy—he was compelled to even abandon Monticello when a British raiding party rode up the “little mountain” and captured his neoclassical home.

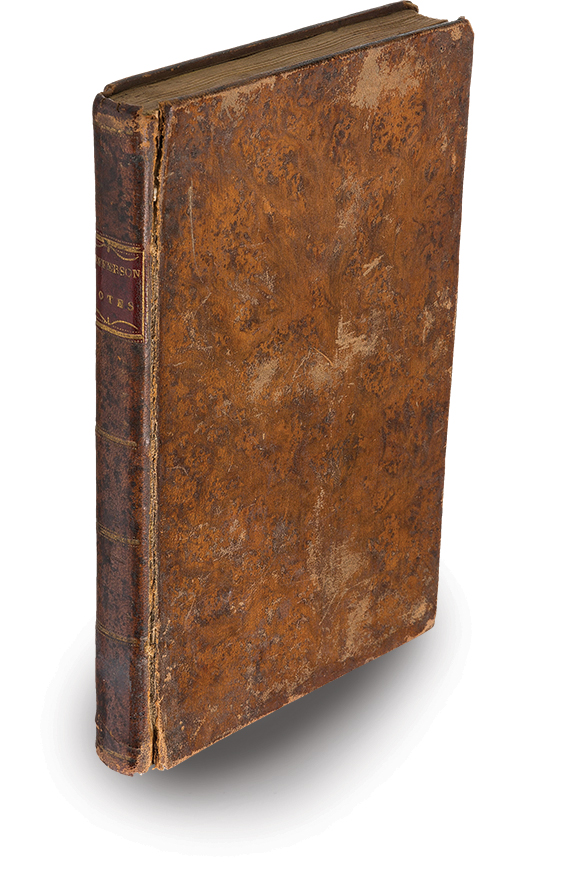

Although Jefferson later termed this troubling period the very nadir of his public career, the termination of his governorship in early June 1781 did nevertheless give him the time he needed to focus on the French questionnaire. Organizationally, each query became the topic of a chapter. In December 1781, Jefferson had the first version sent to Barbé-Marbois, but he immediately began enlarging the manuscript—indeed, tripling the length—until it was published in Paris in 1785 and then in London two years later by John Stockdale as Notes on the State of Virginia.

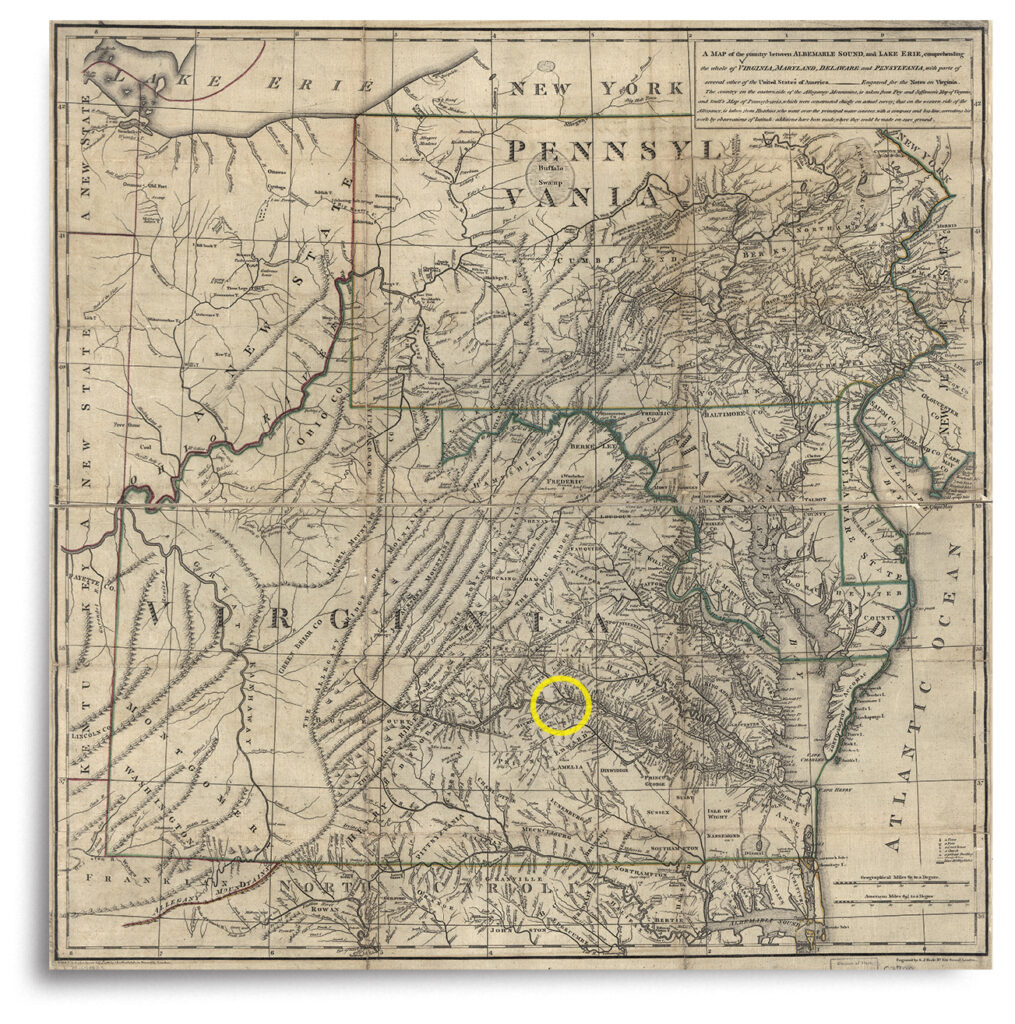

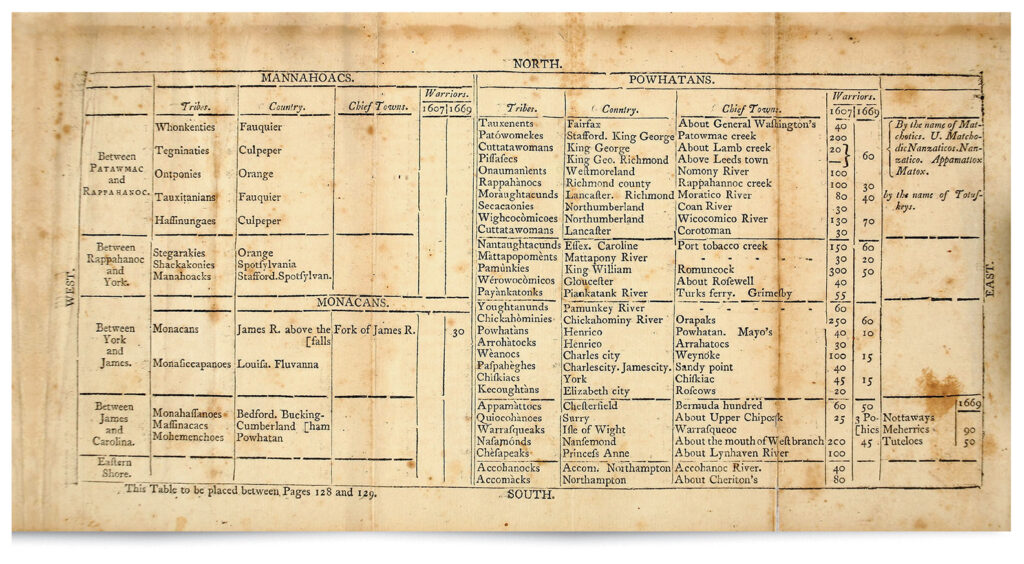

Most of the information came from Jefferson’s personal papers, his large library at Monticello, and his numerous learned correspondents. One query, however, animated him to travel afield. It asked for: “A description of the Indians established in the State….An indication of the Indian Monuments discovered in that State.” After writing about Virginia’s “upwards of forty different tribes”—and compiling a table of their numbers, “confederacies and geographical situation”—the former governor tackled the query’s second section. “I know of no such thing existing as an Indian monument…,” he wrote, “unless indeed it be the Barrows, of which many are to be found all over this country.”

Jefferson penned that these were “of considerable notoriety among the Indians,” and that one stood in his neighborhood. He recalled that, in the mid-1750s, a party of Native Americans “went through the woods directly to it…and having staid about it some time, with expressions which were construed to be those of sorrow, they returned to the high road” about six miles distant. (While some writers claim that young Jefferson, then only 10 to 12 years old, witnessed this incident himself, it is much more likely he heard this story secondhand.)

These Native Americans were most certainly Monacans, a Siouan-speaking people who, in the dim past, had journeyed from the Ohio River Valley across the Appalachian Mountains. Up through the late 1600s, the Monacan Nation—a confederacy of like-speaking Native American tribes—controlled a vast region of the fertile Virginia Piedmont, including the valleys of the Rivanna and upper James Rivers. By the time of the arrival of Europeans in the Piedmont in the 1720s, the Monacan had long since removed to the southwest.

Monacan men stalked elk, deer, and small game through the open woods and sometimes pursued bison over the beautiful Blue Ridge into the Shenandoah Valley. Dressed in animal skins, and sporting wildly cut manes, they adorned themselves with necklaces made of copper they had mined. Much prized, the copper they sometimes traded with the Powhatan, an Algonquin people who occupied Tidewater Virginia to the east. The Monacan and the Powhatan also frequently fought.

The Monacan women raised crops of corn, beans, and squash in the fields surrounding their villages. Often comprising scores of bark-covered domed structures, these villages were surrounded by 7-foot-high palisade enclosures (a feature that made them resemble the English-built forts). One such town, Monasukapanough, had once stood near the Rivanna River in close proximity to the “barrow” in Jefferson’s neighborhood. He noted the connection between the two sites when he wrote that the mound was located “opposite to some hills on which had been an Indian town.”

To better answer Marbois’ query and to satisfy his own curiosity, Jefferson determined to “open and examine” this mound thoroughly. Prior to the excavation, however—in anticipation of what was later termed the “scientific method”—he posited questions he hoped to find answers for in the earth. It was obviously a repository of the dead, but when was it constructed? How was it constructed? Was it true that those interred were the casualties of Native American battles fought nearby? Was it the common sepulcher (or tomb) of just one town? This supposition came from a tradition, Jefferson wrote, “handed down from the Aboriginal Indians, that, when they settled in a town, the first person who died was placed erect and earth put about him, so as to cover and support him….”

When another person died, the dirt was removed, he was reclined against the first, and then the earth was replaced. (In this manner, therefore, a burial mound would grow outward from the center.) Another question—inferred but never stated exactly—was this: Rather than being related to just one Indian village, was this barrow a sacred burial place for an entire section of the Monacan Nation?

Interestingly, a theory at the time—popular among members of the nation’s foremost scientific organization, the American Philosophical Society, which Jefferson had been elected to in 1780—claimed that Native Americans were too primitive to have erected the barrows, also called “tumuli,” which had been encountered in numerous states. Instead, they attributed their construction to a much earlier people descended from either Phoenicians, Israelites, or perhaps even Scandinavians (think Vikings). These ancient “Mound Builders,” they theorized, were subsequently driven away by the barbarous ancestors of the Native Americans with whom they were familiar. Some of the Mound Builders journeyed south, they believed, and founded the Aztec civilization. While Jefferson was certainly familiar with this racist hypothesis, it is unknown whether he was considering it as he began his dig.

Unfortunately, too, the exact date of the excavation is not known. Concerning this important detail—and so uncharacteristic of Jefferson, who was normally minutiae-obsessed—his Notes on the State of Virginia is silent. Historian Douglas L. Wilson, however, who studied the original manuscript at the Massachusetts Historical Society, the “setting copy” for the 1785 Paris edition, has concluded that the dig “must have been performed after…the summer or early fall of 1783 and before [Jefferson] left for Philadelphia on 16 October.”

The circular barrow was large, 40 feet in diameter, encircled by a ditch five feet across and five feet deep. It had been 12 feet high, Jefferson observed, “though now reduced by the plough to seven and a half, having been under cultivation about a dozen years.” Prior to that, it had been covered with a small stand of trees one foot in diameter.

Restored Honor

Finally recognized as an official state tribe by Virginia in 1989, the Monacan Indian Nation has made considerable strides in reestablishing its ancestral legacy. Its headquarters is located on Bear Mountain, Va., not far from Lynchburg. For more information, visit www.monacannation.com.

Jefferson’s poking around quickly established that the mound contained human bones. They were lying in disarray, “some vertical, some oblique, some horizontal…entangled, and held together in clusters by the earth. Bones of the most distant parts were found together, as, for instance, the small bones of the foot in the hollow of a scull…to give the idea of bones emptied promiscuously from a bag or basket….”

These were “secondary burial features,” wrote University of Virginia anthropology professor Jeffrey L. Hantman, “the comingled remains of numerous individuals” who had been initially buried elsewhere, “then moved collectively at designated ritual moments….”

Jefferson marveled at the number of remains he uncovered; the vast majority being skulls, jaw bones, teeth, and the bones or arms, legs, feet, and hands. Some he extracted intact, but others, such as the skull of an infant, “fell to pieces on being taken out” of the mound.

Next began the most commented-upon aspect of Jefferson’s archaeological endeavor. “I proceeded then,” he wrote, “to make a perpendicular cut through the body of the barrow, that I might examine its internal structure. This… was opened to the former surface of the earth, and was wide enough for a man to walk through and examine its sides.” Typical of Jefferson’s writings, this passage disguises the fact that he alone could not possibly have performed this labor. Surely, the “perpendicular cut” was dug by a rather large number of enslaved African Americans, perhaps as many as 30 or 40, whom he had either transported from Monticello or leased from a nearby plantation owner. These sentences, too, reveal Jefferson’s utter insensitivity to the site’s sacred status.

Now the amateur archaeologist was able to determine how the barrow was constructed. “At the bottom, that is on the level of the circumjacent plain,” he wrote, “I found bones; above these a few stones brought from a cliff a quarter of a mile off…then an interval of earth, then a stratum of bones, and so on.”

At one end of the trench he found four strata of bones; at the other, three. The bones in the strata closest to the surface were the least decayed. Down through the ages, therefore, the barrow had grown taller with recurring layers of bones, stones, and earth. Next, he was able to determine whether any of those interred had fallen in battle. Of the bones he pulled from the mound’s various strata: “No holes were discovered in any of them, as if made with bullets, arrows, or other weapons.”

What of the other questions? Naturally, Jefferson wasn’t able to determine when the Monacan burial mound was initiated, but—thanks to his methods—he was able to answer two others. For the following reasons, he wrote, it was obviously not one town’s common sepulcher: The number of skeletons it contained (he “conjectured” 1,000); None of them were upright; The bones lay in different stratas, with no intermixing; And, the “different states of decay in these strata” seemed to indicate “a difference in the time of inhumation.” This burial mound, therefore, must have appertained to a fairly large region of the Monacan Nation. “Appearances certainly indicate,” he wrote, “that it has derived both origin and growth from the accustomary collection of bones, and deposition of them together….”

In the balance of his response to the aborigine-related query, Jefferson briefly mentioned two other barrows (one of which also contained human remains), presciently noted “the resemblance between the Indians of America and the Eastern inhabitants of Asia,” and urged the collection of Native American vocabularies so that those skilled in languages could “construct the best evidence of the derivation of this part of the human race.” He concluded with a seven-page table listing the tribes residing within, and adjacent to, the United States, their names, approximate numbers, and the locations of their tribal lands.

Ambitious in scope, Notes on the State of Virginia—with its double-entendre title—won for Jefferson considerable notoriety. In 1785, the year of its French publication, Secretary of the Continental Congress Charles Thomson, a fellow member of the American Philosophical Society, called it “a most excellent natural history not merely of Virginia but of North America and possibly equal if not superior to that of any country yet published.”

Wrote English professor William Peden, who edited a 1954 edition of the work: “The Notes on Virginia is probably the most important scientific and political book written by an American before 1785; upon it much of Jefferson’s contemporary fame as a philosopher was based.”

And no small amount of that fame was due to the “sage of Monticello’s” archaeological dig (the only such of his lifetime). Unfortunately, other than what was published in Notes on the State of Virginia, there is no other information about the Monacan burial mound. Jefferson left no field notes. Its exact location has never been pinpointed, although many individuals have tried, including professor Hantman and a team of anthropology students from the University of Virginia.

Unfortunate, too, is the fact that Jefferson never mentioned refilling the trench. If it was indeed left open, the examined remains strewn across the ground, the Rivanna River, which frequently inundates the plain upon which the mound stood, would have washed it away within a few decades. Jefferson obviously believed that the benefits of scientific inquiry greatly trumped the barrow’s importance to the Monacan people.

All that being said, the dig was nonetheless a major scientific achievement. “The importance of Jefferson’s experience and his report of it cannot be overstressed,” wrote science historian Silvio A. Bedini, “for he introduced for the very first time the principle of stratigraphy in archaeological excavation.” With this discipline, examining the layers—“strata,” Jefferson called them—provides a calendar for determining the age of items or human remains contained therein. In his description, Jefferson “not only indicated the basic features of the stratigraphic method, but also virtually named it,” wrote German archaeology writer C.W. Ceram, “although a hundred years were to pass before the term became established in archaeological jargon.”

Most important is the fact that thanks to his excavation of the Monacan Indian burial mound—and the detailed account of his posited questions and scientific methodology—Thomas Jefferson became known as the “father of American archaeology.”

Rick Britton is a historian and cartographer who lives in Charlottesville, Va., in the shadow of Thomas Jefferson’s “Little Mountain.”

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.