A civil case involving property lines finds a Founding Father battling a neighbor

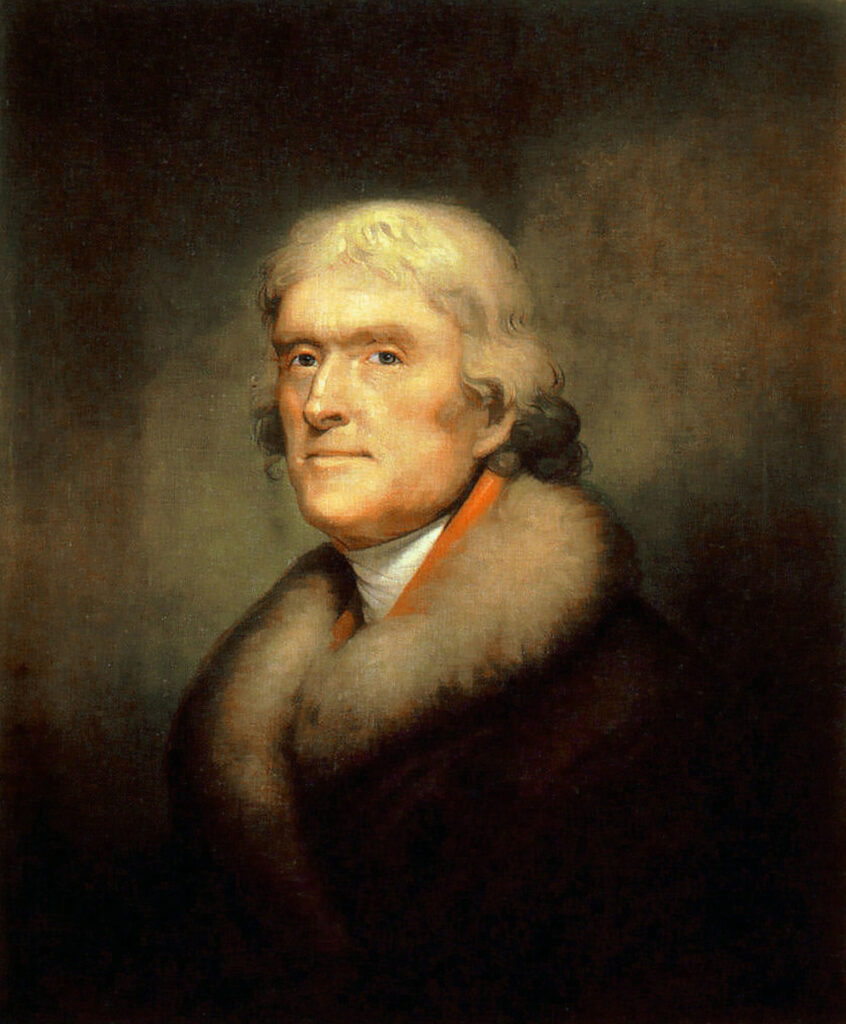

On a brisk November day in 1809 that foreshadowed an unusually cold winter in the Virginia Piedmont, a knot of men had assembled in a strand of old-growth oaks, cedars, and beeches along Campbell County’s Ivy Creek, four miles southwest of Lynchburg. First in rank among those gathered was Thomas Jefferson, fresh from the presidency. Now retired, Jefferson, 66, was settling into private life at his mountaintop home, Monticello, 80 miles northeast, while also building a residence at his 4,000-acre plantation Poplar Forest, which adjoined the land on which the group was standing. Jefferson had in mind to establish at Poplar Forest a tranquil retreat in which an ex-president might escape public life and rekindle his creativity. The other principal in the party was local landowner and planter Samuel Beverly Scott.

Jefferson and Scott were there to settle a dispute over the ownership of a small parcel attached to Poplar Forest and to which each claimed title. Jefferson’s surveyor had run a transect showing that the parcel Scott claimed to be clearly within Jefferson’s boundaries, which seemed to settle the matter. Jefferson later recalled, “It was understood by those present that Scott yielded to this evidence & expressed his conviction of my superior right & I thought it settled and sold the land.” Jefferson returned to Monticello, where within the month he learned that Scott instead had taken possession of the disputed parcel. Legal warfare began between a soldier of the Revolution and a maker of the Revolution.

Well before the tract in question became a legal battleground, Jefferson’s obdurate neighbor had endured terrifying combat on actual battlegrounds. Samuel Beverly Scott, a native of Campbell County, was born March 14, 1754, the fifth of seven sons born to Thomas and Martha Scott. Literate but not highly schooled, young Scott enlisted as a lieutenant in the Virginia Cavalry at the start of the War of Independence. The shift of British offensive operations to the Southern colonies landed him in multiple engagements. At the Battle of Savannah, Scott served as captain of the Georgia Cavalry. On January 18, 1777, he accepted a commission as a major in the Virginia militia. He was serving in that command at the time of the southern campaign’s largest, most hotly contested action—the 1781 Battle of Guilford Courthouse. At Guilford Courthouse, deployed in the second of three defensive lines amid intense artillery salvos, bayonet charges, and galling musket fire, Scott was wounded. He left the army and returned to Campbell County, where he married Ann Roy, bought 400 acres, and with slaves he had inherited started growing tobacco. By 1790 he had built a handsome Georgian manor house, Locust Thicket, which still stands on Lynchburg’s Old Forest Road.

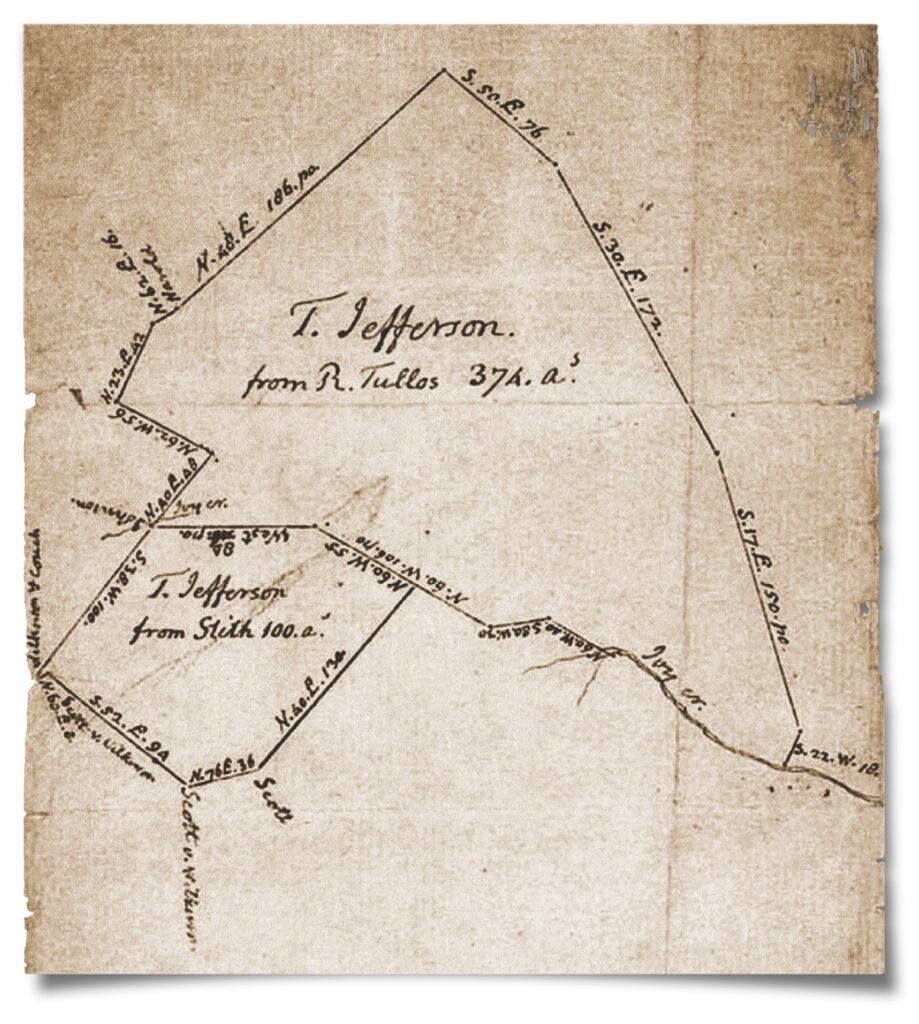

Scott used his inheritance and income from his plantation to acquire other rural tracts west of Lynchburg. He also bought property in that city, including a tavern, a store, a smokehouse, and a lumber warehouse. He made his mark not only as a gentleman of the landed class but through public office, serving as justice of the peace and as high sheriff of Campbell County. Like other farmers of the late 1700s, Scott expected agriculture to be his future and that of his children. He had for years coveted vacant land along Ivy Creek adjoining the southern portion of his 400-acre tract. On the basis of a survey he commissioned in 1803, Scott was issued a patent in 1804 for a plot of 54¾ acres, skirting Ivy Creek at the northern end of Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest. This parcel became the core of the land case that brought the disputants together in November 1809.

Generally quiet, peace-loving, and high-minded, Jefferson felt genuine animosity toward few opponents and critics. Not so Samuel Scott, seen at times as intemperate and often described as an irascible drunk. Testifying to his character in a different trial, a witness said, “I thought him extravagant on the subject of the people of Lynchburg when he spoke of them as a set of fops, whores, rogues and rascals.”

The Jefferson/Scott land dispute had legal and personal roots. Jefferson had inherited Poplar Forest from his father-in-law, John Wayles, in 1773. Wayles had bought the property only a few years earlier from one Richard Stith. Since coming into Jefferson’s hands, the property, run by overseers, had been a productive estate on which many of Jefferson’s enslaved workers operated a large agricultural enterprise that was, in his words, “the most tranquil, healthy, and independent [occupation].” In 1806, anticipating the end of his second term as president, Jefferson began building at Poplar Forest an elegant and distinctive octagonal brick structure of classical design that he gave the same name as the plantation.

For all his tangible assets, Jefferson was hard-pressed by heavy liabilities. Besides chronically living beyond his means, he was carrying substantial debt he had assumed from the late John Wayles. To whittle his indebtedness, he decided to sell a piece of land at the north end of Poplar Forest. On November 15, 1809, he had 474 acres surveyed. Of that parcel, about 100 acres along Ivy Creek was known as “Stith’s Entry.” The name referred to Richard Stith, who had sold Poplar Forest to Wayles. Stith had had the land surveyed in advance of selling; Wayles reimbursed him for that expense. In bequeathing Poplar Forest to his son-in-law, Wayles provided no record of Stith’s survey or patent, only a receipt for the survey that Wayles gave Jefferson. Stith’s Entry touched on a small section of Scott’s holdings, including the 54¾ acres along Ivy Creek that Scott thought he had acquired in 1804. Though the dollar had become the official medium of exchange in 1792, pounds, shillings, pence, and farthings were still in use. This explains Jefferson’s reference to a sale price of £1200 agreed upon with buyer Samuel Harrison in his Notes on Ivy Creek Lands and a November 17, 1809, letter to his agent, James Martin, in which Jefferson writes, “…I inclose [sic] you an authority to sell my Ivy creek lands on the terms then stated; that is to say for 1200 pounds paiable [sic] one third in hand, a third at the end of the year…” That price—today, about $95,000—would start flowing Jefferson’s way in 1810, assuring him of a revenue stream that would keep him current with his obligations.

Despite the extreme winter of 1809-10 work on Poplar Forest, residence and plantation, continued. Anticipating that the following April would bring Harrison’s first installment payment, Jefferson was shocked on December 27, 1809, to read a letter from his overseer at Poplar Forest.

“Strang to tell that Superior man of obstanancy Scot has actuly Commenced Cleearing & building of negres houses on Stithss Entry mr harrison seas he expects us to keep him from injuring of the land untill he can git possession,” the overseer wrote. “I went to See him [Scott] on the Subject & gave him notis that he mout expect to be delte with as the law directed in Such cases but he Sais he Shall perseede in defiance of law or gospel.”

Soon others were carrying tales of Scott’s action to Jefferson—and to Harrison. Fearing Scott would clear his parcel of valuable timber, Harrison insisted that Jefferson, who now was in the position of seeming to have sold land without having clear title to it, protect the property from further damage. Until Jefferson could prove his free and legal claim to the land, Harrison told his friend, he was not going to pay his April 1, 1810, installment. The situation worsened. Harrison and others urged Jefferson to travel to Poplar Forest and deal with Scott, whose audacity in appropriating the acreage suggested the case would not have a neighborly resolution.

Citing the weather and his age (he was almost 67), Jefferson held off going to Poplar Forest until spring. He met Scott on March 31, 1810; the other man had brought one of his sons, his overseer, and his lawyer, a fellow named Devaney. Things did not go well. Afterward, an exasperated Jefferson wrote to his attorney, “I ordered the people off but his [Scott’s] overseer, his son & his lawyer (mr Devany) ordered them not to go.” Jefferson noted that the overseer had come armed with pistols, “& the young lad foolishly vapouring [threatening] with them.” Scott declared that if Jefferson wanted the land, he would have to recover it by legal action.

Jefferson was in a fix. If a court were to find that Scott owned the contested acreage, Jefferson’s sale to Harrison would be void, and Jefferson would be in default. The former president initiated a writ of dispossession. That April 6-10, 1810, an ordinary jury of 12 men and a grand jury of 24, appointed by the justice of the peace for Campbell County, met to consider Jefferson’s petition. Before the juries convened, Scott behaved so bizarrely that Harrison told Jefferson, “…if the Jury Should Decleare the Land yours, I would Suggest the propriety of your having somebody ready to put in Possession, as I have no Doubt but Scott (who puts all Law at Defiance), will Endeavor to regain it, Immideatly by force.”

Both juries regarded Scott’s case to be “so groundless that they would not even retire for consultation.” Each jury found Scott to have taken possession of the land forcibly, and authorized that possession be redelivered to Jefferson. Scott did not attend the hearing. His counsel—perhaps one or both of his sons—another lawyer or two, and his overseer—led Jefferson to believe that as long as Jefferson agreed not to institute any prosecution against Scott, Scott would cause him no more trouble. On April 7, 1810, to Jefferson’s great relief, Harrison made his first payment on his 474-acre purchase along Ivy Creek. Jefferson gave Harrison all documents related to his ownership of the parcel should Harrison have problems with Scott.

A severe stroke had kept Scott from attending the April 1810 court hearings. The ischemic attack left the old soldier speaking indistinctly for about 18 months, but by April 1812 Scott was capable of writing. That month he filed a Bill of Complaint against Jefferson and Harrison alleging multiple wrongs. He said that the juries of April 1810 had dispossessed him at a time when he was confined to bed and unable to attend to business. He said he had a valid 1804 patent to the land. He denied taking possession of the contested parcel forcibly. In reference to the Stith’s Entry acreage Scott claimed he was “…firmly persuaded that there never was an actual survey made by Jefferson or the person under whom he [Jefferson] claims.”

To rebuff Scott’s formal complaint, Jefferson and Harrison probed the Stith’s Entry’s title history. Lacking a record of Stith’s survey or patent, Jefferson needed somehow to prove that in the early 1770s Richard Stith had surveyed the parcel and sold it to John Wayles, who reimbursed Stith for the survey and in 1773 bequeathed the parcel to Jefferson. In search of the missing paperwork, Jefferson enlisted others to comb early patents, surveys, plats, field notes, and memoranda. The Stith survey never turned up. As proof of ownership, all Jefferson could proffer was a copy of a December 27, 1770, receipt for the £6 Wayles paid Stith to cover the survey cost. Both Jefferson and Harrison filed written legal answers to Scott’s complaint, and during 1812 both men provided depositions obtained from multiple individuals who had memories of the contested parcel’s history.

Scott provided nothing other than his bill of complaint. His opponents had attacked his character, and it was clear that if the matter came to a hearing they would do so again in court. “I doubt if Scott will not try to keep it hanging up for his own gratification,” Jefferson wrote later. “For whenever he is sober enough to think, which is extremely rare, litigation is the only food of his mind.” In June 1814 the judge of the Superior Court of Chancery for the Richmond District found for Jefferson, dismissing Scott’s claim and leaving those 54¾ acres in Jefferson’s hands.

Jefferson’s private correspondence conveys his belief that he owned the land in question through inheritance. He focused intently on the case, which tied up payments from Harrison that Jefferson needed to pay creditors. The author of the Declaration of Independence was in the awkward position of having embroiled a good friend in a lawsuit. It is unclear why back in 1809 Scott had acceded to Jefferson’s claim, or why later that year he decided to claim and begin to clear the property, or why, after a stroke in 1810, he initiated civil action. In a later trial related to Scott’s will, his family physician, Dr. George Cabell, testified “As to his state of mind, I considered it good, except when intoxicated, until April 1810 when he had a paralytic stroke, perhaps a year or more, after which he recovered his mental faculties so far as I could judge, and his mind was sound except when intoxicated or under the influence of fever in his last illness.”

Scott may have held a secret grudge against Jefferson or the Wayles family, or truly believed the land to be his. He lived on at Locust Thicket until his death in 1822; he is buried there in a private cemetery. Jefferson last visited Poplar Forest in 1823, when his grandson, Francis Eppes, moved into the stately, but unfinished and unrefined mansion. When Jefferson died in 1826, much of his estate had to be sold to pay creditors, but he left Poplar Forest to young Eppes, hoping the plantation would stay in the family. However, Eppes soon sold the property to neighbor William Cobbs, a farmer, for a fraction of its recorded value. Cobbs had married Marian Stannard Scott, Samuel Scott’s daughter. The irony of Marian Scott as mistress of Jefferson’s charming and beloved Palladian villa—a far greater prize than the 54¾ acres her father lost to Jefferson—prompted a Scott descendant to remark, “We won the case.”