Passengers riding the Orange & Alexandria Railroad in early 1864 witnessed a bleak landscape disfigured by nearly three years of war. “Dilapidated, fenceless, and trodden with War Virginia is,” Walt Whitman recorded on a trip from Washington, D.C., to Culpeper, Va., that February. “Virginia wears an air of gloom and desolation; no fences, no homes—nothing but the debris of destroyed property and continuous camps of soldiers,” seconded a U.S. Christian Commission representative. “There was nothing,” opined a newspaper correspondent, “absolutely nothing but the abomination of desolation.”

The Union Army of the Potomac’s winter camps surrounding Culpeper depended on the railroad for provisions, munitions, and forage. Keeping the army supplied required 40 locomotives running daily along the 70-mile stretch of tracks that were vulnerable to floods, prone to accidents, and often attacked by Confederate cavalry raiders. Yet such was the efficiency of the U.S. Military Rail Road’s management that when 22 miles had been destroyed by retreating Confederates the previous fall, the line was restored within days, and the high bridge over the Rappahannock River was rebuilt in 19 hours.

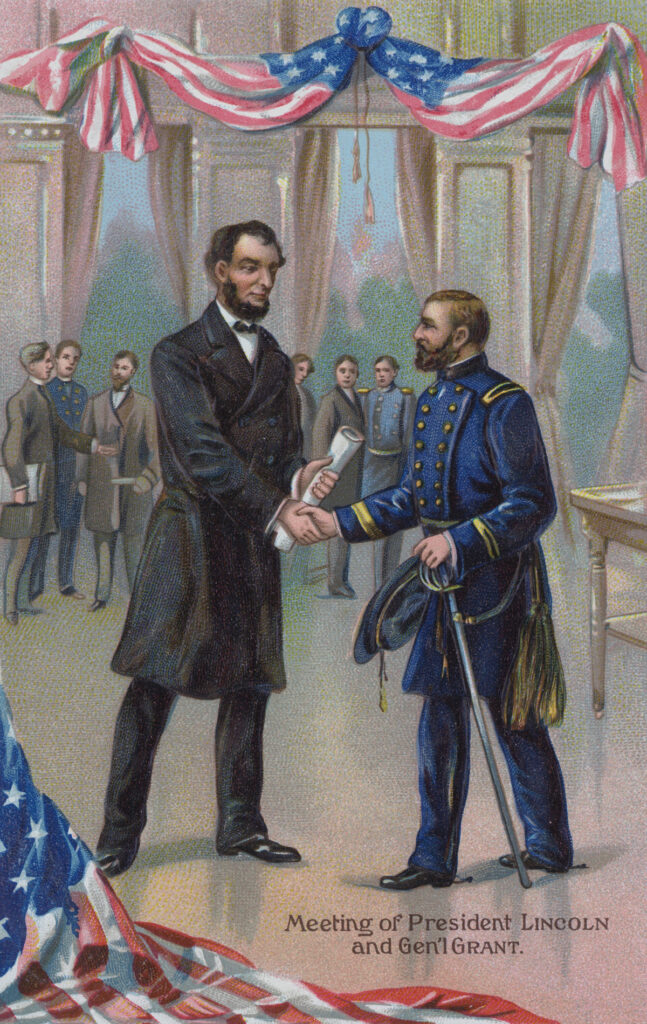

On March 10, a special train comprised of a locomotive and two cars chugged its way south. Aboard the first car was a detachment of soldiers, but riding in the other was the United States’ new general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and a small party that included staff officers, his son Fred, and his principal political sponsor, Congressman Elihu B. Washburne. Grant had formally received his promotion the day before from President Abraham Lincoln in a ceremony attended by the Cabinet. There was awkwardness—Grant was unfamiliar with Washington and nearly all its officials, including Lincoln, whom he had only just met, and the general-in-chief was a stranger to them. More discomfiture lay ahead at his destination—the winter camps of the U.S. Army of the Potomac.

No one recorded details of that six-hour trip aboard a vulnerable train traversing a terrain rendered even sadder by heavy, cold rain, but the trip’s significance could hardly have been lost on Grant. The man who less than three years before had worked as a clerk in his father’s dry goods store in Galena, Ill., now commanded more than 800,000 soldiers in 19 departments in all Union states and several in the Confederacy.

Over the last two years, Grant had won victories at Fort Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga and demonstrated tenacity, audacity, ingenuity, and adroitness. But his character was what most impressed his closest friend, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, who had recently told him that he was “as unselfish, kind-hearted and as honest as a man should be.” Sherman added that Grant’s most outstanding quality was his “simple faith in success you have always manifested, which I can liken to nothing else than the faith a Christian has in a Savior.”

Grant would call on those strengths as he faced a more complex challenge than any he had yet faced. He knew he would be directing armies in a year that would see a wartime presidential election that could itself determine the war’s outcome. The new general-in-chief also recognized that winning victories in the coming campaigns would be key to winning at the polls in November.

Rolling Toward Brandy Station

Grant had been promoted to provide a more vigorous prosecution of the war. That Grant, on his first full day as general-in-chief, left Washington to meet the principals of the Army of the Potomac underscored how closely was its success tied to the Union cause. Moreover, Grant’s plans had changed. Whereas he had intended to exercise his new overall command while headquartered in the West, he now understood that he needed to be near Washington to shield the Army of the Potomac from political intrigue and that Lincoln specifically intended that he provide close command oversight. He knew he would soon deliver a mixed message to the army’s leadership.

Grant fully recognized the risks his promotion posed. After his victory at Vicksburg, newspapers had reported that Grant would replace Maj. Gen. George G. Meade as the Army of the Potomac’s commander. The report first appeared in a little-known New York paper, the Express, and might have originated with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. In addition, some, perhaps Congressman Washburne among them, advocated Grant transporting his army to the Eastern Theater and superseding Meade. Talking Stanton out of it was then General-in-Chief Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, Grant’s departmental commander earlier in the war, and Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, who had observed Grant at Vicksburg.

Once it became clear he would not be transferred, Grant expressed relief. It was “a matter of no small importance,” he wrote Washburne, that the change not take place. In that letter and in an earlier missive to Dana, Grant explained the reassignment “could do no possible good.” Noting that the Army of the Potomac was led by “able officers who have been brought up with that army,” the general anticipated that they would resent having an outsider placed over them. Commanding the Army of the Potomac, he continued, meant, “I would have all to learn.”

Even in mid-February 1864, with his promotion to general-in-chief all but certain, Grant remained reluctant, telling a West Point classmate that he was “thankful” that he had not been transferred. Commenting to his wife, Julia, that same week, the general intimated that were he to receive the top command, he would not be confined to Washington. Grant mused they might see more of each other as he would be traveling regularly between his Western headquarters and the Eastern Theater and could stop to see her wherever she elected to live.

But now Grant was about to begin his acquaintance with the most prominent, and unlucky, of U.S. armies. The Army of Potomac was quite unlike the usually victorious forces Grant had led in the West. Still looming over the army that winter was the shadow of its creator, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Though dismissed 17 months before, McClellan’s influence endured, most notably among the army’s senior generals, nearly all of whom had received their first promotions while under McClellan’s command. To many of these men, McClellan bequeathed his caution and lack of urgency that hampered its operations. He also left an army culture of political engagement with Washington that undermined its effectiveness. Grant’s suspicions were correct—he was bringing a new style, and he and those he brought with him would be regarded as outsiders.

Since McClellan’s dismissal, three men had commanded the army—Ambrose Burnside, Joseph Hooker, and Meade. Burnside and Hooker were dismissed for their battlefield and command failures and, partly, because their subordinates had lost faith in their leadership. The army had won but one clear-cut victory, and it on the home ground of Gettysburg, and had repeatedly been manhandled by the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia led by General Robert E. Lee.

For his part, Meade had been so criticized after his victory at Gettysburg that he had repeatedly offered to resign. Five days before Grant arrived, Meade had testified before Congress refuting false allegations made by several generals and an array of political opponents who sought to have him replaced. His hold on command was tenuous, and Meade would not have been surprised if Grant was bringing word that he would be sacked.In short, Grant was about to engage an army that was, in the words of Bruce Catton, “badly clique-ridden, obsessed by the memory of the departed McClellan, so deeply impressed by Lee’s superior abilities that its talk at times almost had a defeatist quality.”

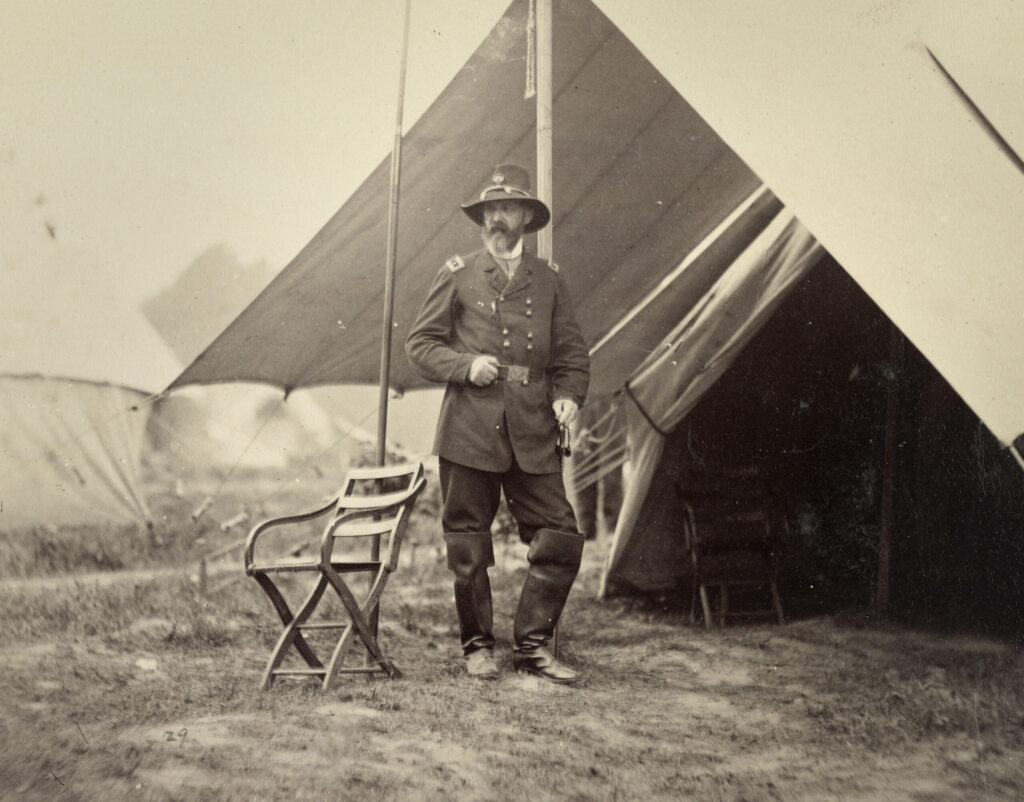

At 3 p.m., Grant’s train pulled into rain-soaked Brandy Station, Va., the army’s principal supply depot, described as a “vast domain of smoke, guns, and mud-stained soldiers.” There, on the platform surrounded by barrels of beef piled high around the tracks, were two of the army’s principal staff officers, chief of staff Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys, and quartermaster Brig. Gen. Rufus Ingalls. Humphreys was substituting for Meade, his “slightly indisposed” superior, while Ingalls was presumably along to greet his old friend and West Point roommate. Meade’s absence might have appeared to a more protocol-conscious general like a slight, but there is no record of Grant taking offense.

After the train rolled to a stop, guards disembarked from the first car while officers and civilians detrained from the second. Among them was Grant. The only thing remarkable about him, thought Dr. E.W. Locke, was that he was smoking. “His dress is very plain, eyes half closed, he takes little or no notice of anything,” Locke continued, observing that a “very few officers, and as many men, came, took a hasty glance, and have now gone back to their quarters, most of them shaking their heads, and some saying, ‘Big thing.’”

The party rode a four-horse spring wagon to Meade’s headquarters three miles away, where they were greeted by the camp guard consisting of details from four regiments. One of the army’s finest bands struck up “Hail to the Chief” and other tunes, but rain prevented a more elaborate ceremony, which was just as well. The new general-in-chief never learned how to make an entrance, and if he took note of the welcome, no one noticed. Worse, his hosts could not have known that their new commander was tone-deaf and sometimes found the sound of music excruciating. Grant once confessed—or joked, we know not which—he knew but two tunes, one that was “Yankee Doodle” and one that was not.

Meade, clad in a common soldier’s jacket, opened his tent door to greet his new chief. Exactly what occurred during that meeting is muddled. Most historians have accepted Grant’s account in his Memoirs that Meade offered to step aside in favor of someone Grant knew better, suggesting specifically Sherman. Grant wrote that he was so impressed by Meade’s selflessness that he immediately assured Meade that he had “no thought of substituting anyone for him.” Meade’s more immediate account, written the evening of the meeting, is cryptic, mentioning only that Grant had been “very civil, and said nothing about superseding me.”

But Grant had considered sacking Meade. One of Grant’s aides recorded in his diary on March 10 that Grant had considered replacing Meade with Maj. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith, who had impressed the new general-in-chief in Chattanooga, but that there was now to be “no change.” Many published rumors had predicted that Meade would be fired, mentioning several different generals, and Smith was listed as among the leading candidates. Meade, who knew and disliked Smith from their time serving together earlier in the war, could not have been comforted by knowing that Smith had accompanied Grant on his visit to the army.

In Smith’s telling, Grant had found that the War Department preferred to keep Meade in command and that he accompanied Grant to Brandy Station only at the latter’s insistence. He discreetly spent the night not with Grant’s entourage but with old Army friends. Grant had lobbied for Smith’s promotion to major general and would later assign him to lead a corps in the Army of the James.

Grant recalled that there was “prejudice” against Smith in the Senate and that only after he persisted had the promotion gone through. As he ruefully recorded in his Memoirs, however, “I was not long in finding out that the objections to Smith’s promotion were well founded.” Meade continued to fret; as late as March 17, he was still worried that Smith would take his place.

First Impressions

Just when and how Grant decided to retain Meade is elusive. Grant was apparently surprised to learn in their initial meetings that Lincoln and Stanton were not looking for a change. Meade hailed from a politically important state, Pennsylvania, and was the only army commander who had bested Lee, making him difficult to fire.

Given the infighting that had raged for months among many in the Army of the Potomac, the administration must have noted that most Army generals continued to support Meade. Moreover, Grant knew he was an outsider in an army that did not treat outsiders well, and replacing Meade would only compound that problem. Finally, both Lincoln and Grant recognized that much of the effort to oust Meade came from those whose bad-faith motives ought not to be rewarded.

Because Meade’s frequent letters to his wife survive, we know much about his frame of mind during the months preceding Grant’s arrival. Replying to his wife’s late-1863 question, Meade wrote that he knew Grant slightly from the Mexican War, where he was considered a “clever young officer, but nothing extraordinary.” Judging from the then-common usage of the adjective “clever,” the army commander apparently thought of Grant as amiable or well-mannered rather than intelligent.

After explaining that Grant had been compelled to resign his commission because of his “irregular habits”—a reference to Grant’s drinking—he listed Grant’s strength as his energy and “great tenacity of purpose.” Still, he could not resist observing that there was little basis for comparison between the U.S. armies in the East with those in the West, claiming that his army had faced an adversary that was better led and composed of better troops.

Meade followed up his brief March 10 letter four days later. In that missive, Meade gave a longer description, saying he was “much pleased with General Grant,” and that he had shown “much more capacity and character than I had expected.” He told his wife that he had offered to step aside as army commander if Grant wished to replace him with a general he knew better. Meade related that Grant replied with a “complimentary speech,” and disavowed any intention to replace him. Then Grant delivered the less welcome news: He intended to accompany the army during the spring campaign.

“So that you may look now for the Army of the Potomac putting laurels on the brows of another rather than your husband,” Meade concluded, a strikingly prescient prediction. Meade returned to his impression of Grant in a March 16 letter, saying that he was “most agreeably disappointed in his evidence of mind and character. You may rest assured he is not an ordinary man.”

If Meade’s words are condescending, hinting at being pleasantly surprised by Grant’s abilities, that view was shared by top subordinates. “Agreeably disappointed,” although a curious phrase, seems to have reflected a consensus. The army’s senior corps commander, Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, wrote to his sister that he had “spent an evening with [Grant], and was most agreeably disappointed, both in his personal appearance and his straightforward, common-sense view of matters.”

Despite news that Grant might command the army directly, Sedgwick noted, “[G]ood feeling seemed to exist between him and General Meade.” General Humphreys agreed, telling his wife in a March 10 letter that he was “agreeably disappointed in Genl. Grant’s appearance,” describing the new general-in-chief as having “an intellectual face and head which at the same time expresses a good deal of determination.”

Striking a discordant note was Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren. Grant, he said, “seems much more vivacious than I supposed and did not look at me with any apparent eye to discerning my qualities in my face.” Warren perhaps did not mean it this way, but he seemed to fault Grant for failing to perceive his brilliance, an early sign of a personal conflict to come.

The weather having not improved, Grant abandoned plans to visit the various corps, and returned to Washington on March 11. He spent much of that afternoon conferring with Halleck, now his Washington-based chief of staff, and then with Lincoln and Stanton. When Grant said he intended to depart for Nashville that evening, Lincoln implored him to stay for dinner at the White House. Grant declined, citing the urgency of returning to the West, adding that he had “enough of the show business.” Besides, he added, “a dinner to me means a million dollars a day lost to the country.” Lincoln ruefully told the gathering of senior generals and Cabinet officials arriving for dinner that Grant had to leave unexpectedly, and therefore, the evening was “the play of Hamlet with Hamlet left out.”

Grant had earlier promised to stay the night, so there was something precipitous in Grant’s immediate departure for the West. It may be that after a stressful 48 hours, and now knowing he would soon return to the Army of the Potomac’s camps, Grant urgently wished to see familiar surroundings and subordinates. Ahead, he now knew, lay a complex relocation for his staff and family and the transfer of his departmental command to Sherman. He now had a firmer sense of how much there was yet to learn and do.

Nevertheless, he had achieved a favorable first impression, demonstrating that he was a quick study who had quietly impressed strangers with his intelligence, determination, humility, common sense, and what Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells noted was a “latent power.” In adjusting to Lincoln’s preferences to base his command in the East and accompany the Army of the Potomac still led by Meade, Grant showed a quick willingness to follow without complaint his civilian superior’s priorities. That augured well for their future partnership.

Official Washington seemed not to mind that Grant’s visit was brief, with several observing approvingly that Grant was “all business.” Still, as the train chugged away, Grant, again alone with his thoughts and cigars, could not know that he had taken his first sure steps on a momentous road that would, less than 400 days later, end in a stillness at Appomattox.

William W. Bergen, an independent historian based in Charlottesville, Va., has had essays published in the University of North Carolina’s Military Campaigns of the Civil War series. He also has worked as a paid guide at Monticello.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.