It took him 10 years and two wars, but Canadian fighter pilot Omer Levesque finally got his fifth victory in the skies over Korea.

On March 31, 1951, Joseph Auguste Omer Levesque became the first British Commonwealth pilot to shoot down a MiG-15 during the Korean War. It was his fifth aerial victory, qualifying him to join the honored ranks of Canadian aces. But the Quebec native had actually notched his first four kills a full decade before, during World War II’s early years. Fortunately for Levesque, the combat skills he had acquired flying Spitfires over France would serve him equally well in the cockpit of an F-86 Sabrejet over the Yalu River.

Newly trained Royal Canadian Air Force pilot Omer Levesque had arrived in England on May 20, 1941, at a time when Allied airmen faced extremely dangerous combat conditions over Europe. As the Royal Air Force took the offensive after the Battle of Britain, it faced a determined Luftwaffe whose pilots were highly motivated and well trained. What’s more, German airmen who survived being shot down could be back in the air the next day, while British pilots downed over Europe usually ended up in POW camps.

Born in Montreal to French-speaking parents, Levesque had been interested in joining the RCAF since boyhood. But his English wasn’t very good, so instead he joined a local militia unit, where he was quickly promoted to lieutenant. Levesque attended Ottawa University, Canada’s first bilingual school, later transferring to the RCAF as an aircraftsman second class. He graduated from Elementary Flight Training School on April 1, 1941, after 160 hours of basic flight instruction in a de Havilland Tiger Moth. The graduating class consisted of seven pilots, only two of whom would survive the war.

Assigned to No. 55 Operational Training Unit in Scotland, Levesque took an additional 65 hours of flight training and became familiar with the Hawker Hurricane. His combat career commenced with the RCAF’s veteran No. 401 “Ram” Squadron, which flew the Supermarine Spitfire V. Looking back on his introduction to the Spit, he said: “We’d heard so much about it, and it was really beautiful—unexpectedly beautiful—to fly. It was so smooth and responding to the engine. The weight of the aircraft wasn’t all that much. It had thin wings, and the Hurricane had very heavy wings.”

By that September Levesque was a seasoned combat pilot who had gained a nickname, “Trottle.” Reflecting on his experience, he put it bluntly: “Most new pilots bought it after two or three sweeps. Once we nearly lost the whole squadron, losing nine pilots in one sweep. We were just about decimated. In the Battle of Britain you could bail out and be home the same day, but over France you were a prisoner. And the Germans were so powerful and cocky in those days. They’d sometimes chase us right back over the Channel. They were wiping us out.” Advancement was rapid because of the high mortality rate among pilots. An officer told Levesque, “Even if you don’t want to be an officer, you have to be, because we can’t have an NCO leading a flight.”

On November 22, 1941, Levesque’s squadron encountered a new German fighter for the first time. The Spitfires had crossed the Channel at Dover and climbed to four miles when suddenly one of the pilots shouted “Bandits!” over the radio. As Levesque squinted into the sun, a flight of enemy aircraft flashed past at 400 mph, machine guns and cannons blazing. He had just an instant to glimpse their light blue underbellies, gray and green wings, yellow noses and huge radial engines that looked nothing like the front end of a Messerschmitt Me-109. Even from a distance, he could tell this new plane was faster, carried more armor and boasted more firepower than the Me-109. The lead Spit went down in a ball of orange flame. Levesque’s element leader also went down, but the pilot managed to bail out.

Levesque banked hard right to meet the attackers. “I made a complete circle, saw an enemy aircraft and climbed toward it, getting on his tail,” he recalled. “I got in a pretty good shot…all of a sudden smoke came out the full length of its fuselage. I got him in the fuel tanks but the sealant prevented a fire. He wasn’t finished and dove away, turning to keep from me. But I stayed with him all the way down from 22,000 feet. He went straight down and I kept firing at him, using up just about all of my 120 rounds of cannon fire.”

Recommended for you

The combatants were locked in a deadly duel, spiraling downward in a tight circle. Rivets began popping in the Spitfire’s wings, and Levesque was drenched in sweat, but he managed to get into position and fire everything he had, shredding the German plane. It burst into flames, nosed over and smashed into the ground. “I was pretty close to the ground,” Levesque reported, “and barely got out and pulled up in time myself.” He was among the first British Commonwealth pilots to shoot down one of the recently introduced Focke-Wulf Fw-190A-1s.

Levesque scarcely had time to congratulate himself, as more enemy fighters swarmed in from the nearby base at St. Omer. At this point he broke a primary rule of aerial warfare by flying upward to attack a superior force. But his luck held. He shot down a second German fighter (though it was unconfirmed), and the others quickly scattered.

Back in England, Levesque slumped exhausted in a chair during the debriefing. Asked to report on his claims, he took a deep breath and said: “Sir, I should be dead 20 times. I could have been killed without knowing nutting about it.” The laughter that initially greeted his remarks stopped as Levesque told his story.

“Boy, he’s had it,” somebody in the group muttered as Levesque collapsed in his seat after finishing. But given a 48-hour leave to recuperate, Trottle bounced back. Newly promoted to flight sergeant, he returned to duty his usual cocky self, the proud new owner of an MG sports car.

Levesque was commissioned a flying officer in early February 1942 and assigned to regular patrol duty over the English Channel. He would fight the most spectacular—and final—battle of his WWII career during that same month, in the course of what later became known as the “Channel Dash.”

For more than a year, the British had sought to destroy the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, which lay trapped at Brest Harbor. But when the Germans began a surprise escape run on February 11, 1942, the British were caught largely unprepared. In desperation they attacked with virtually everything they had, even pressing mine-laying units into service.

On February 12, Levesque’s squadron took to the air to protect a hodgepodge mix of British attackers. When a massive air battle developed above the three German ships, Levesque, now a squadron leader, scored hits on an escorting Me-109, for which he received credit. He later described the battle in vivid detail: “You could see a tremendous amount of smoke from those ships. And the flak crews were firing everything they had at any aircraft above them. We got mixed up with a whole bunch of aircraft and we were only 300-400 feet above the ships. Those huge guns were firing at us and big balls were coming up from them. At the same time, German fighters were all over the place. We were really going crazy, skirting in and out of clouds in a fight that lasted 20 to 25 minutes.”

Spotting an Fw-190 dodging “friendly fire”—flak from the ships— Levesque raced toward it. He fired from several hundred yards out, farther away than normal because he was afraid the yellow nose of his Spitfire V would make an easy target, but his aim proved accurate. Levesque saw the German pilot collapse in his cockpit, after which the 190 dived into the sea—the Canadian’s third confirmed kill.

Diving out of a cloud, Levesque found there was an Fw-190 directly in front of him and fired without thinking, scoring his fourth kill. Then another Fw-190 came at him out of a cloud. Although his bullets set the fighter on fire, that kill could not be confirmed.

Suddenly the hunter became the hunted. Cannon shells ripped through Levesque’s engine and tore through his wings. His radio went dead. An Fw-190 had come up behind him while he was preoccupied with his opponents. Levesque spun his crippled plane out of the path of the attacker, who sped past him. Now it was the Canadian’s turn. He dived on the German’s tail and pressed his firing button—but nothing happened. He was out of ammunition.

Levesque headed for home trailing a long cloud of black smoke. His last opponent left him alone, but now flak from the ships slammed into his Spit’s engine. Too low to bail out, his only hope was to ditch in the Channel.

Many Spitfire pilots didn’t survive ditching, since even in calm conditions the fighter’s heavy engine immediately pulled the plane underwater. Levesque yanked back his canopy and struggled to bring the Spit’s nose up as he plummeted toward the Channel. He smashed into a large wave, and the plane immediately started sinking. Knocked out by the impact, Levesque came to underwater, but managed to break free of the fighter. He later told an interviewer: “I woke up. I felt good—it was like a dream. I thought to myself, ‘If I come back from this, there’s nothing to dying.’”

As he reached the surface, Levesque knew he was likely to freeze to death in the Channel’s icy waters. He was only vaguely aware of hands that grabbed him and pulled him out of the water as he lapsed into unconsciousness. He awoke in a dark ship’s hold decorated with a picture of Adolf Hitler.

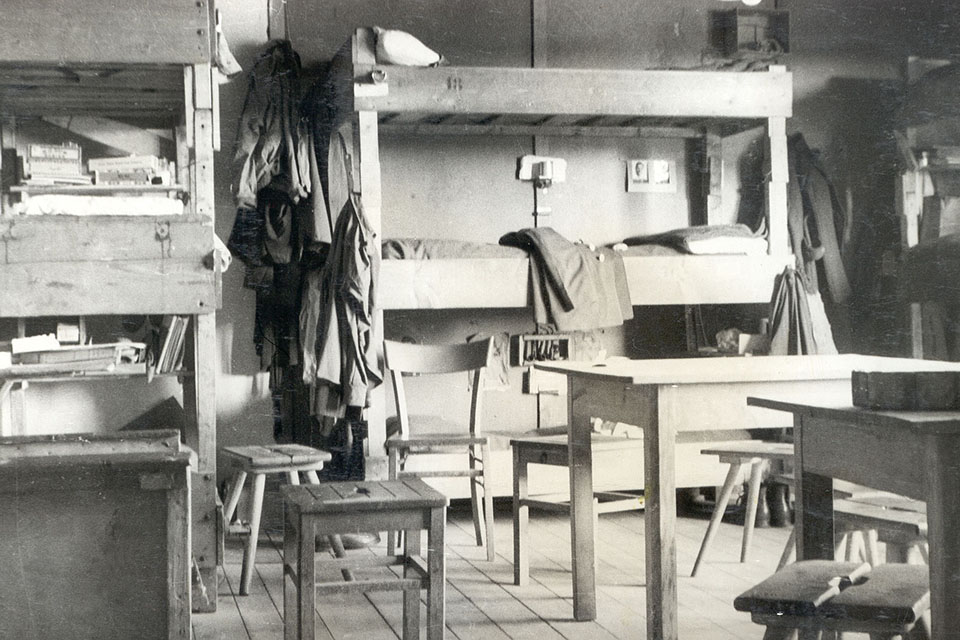

Levesque spent the next three years at Stalag Luft III, a prison camp 100 miles southeast of Berlin intended for captured Allied air force officers. This was the camp from which 76 men made a mass escape on March 24, 1944, inspiring the film The Great Escape. Although Levesque helped dig the tunnels under the camp fences, the escape committee did not choose him to be part of the group that attempted to get away. As it turned out, that was a lucky turn of events: Only three of the prisoners managed to make good their escape, and the Germans shot 50 recaptured POWs in cold blood, among them several of Levesque’s friends.

In February 1945, the prisoners were moved closer to Berlin and placed in a compound surrounded by barbed wire. Levesque never forgot the day when they were liberated: “One morning Russian tanks burst into the compound firing their cannon. They came at 3 in the morning, blowing trees over….”

Levesque returned to Canada in July 1945, and enrolled at McGill University. Although he reenlisted in the RCAF the following year, he managed to complete his degree in political science and economics at McGill. Subsequently assigned to a unit that flew C-47 Dakotas in Canada’s north, he was later transferred to No. 410 “Cougar” Squadron in Quebec, flying the de Havilland Vampire, a sleek new twinboom jet fighter. During his time with 410 Squadron Levesque became a member of the unit’s Blue Devils aerobatic team, which began performing at airshows throughout North America in June 1949. In addition, he set out to test just how far and fast the new jet could fly, at one point making the trip between Montreal and Ottawa in a blistering 8½ minutes.

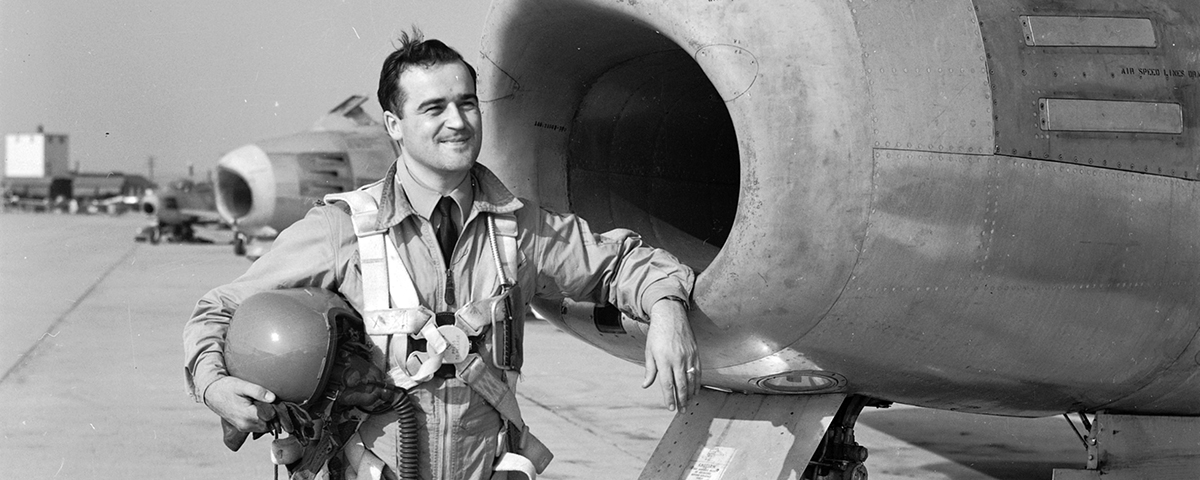

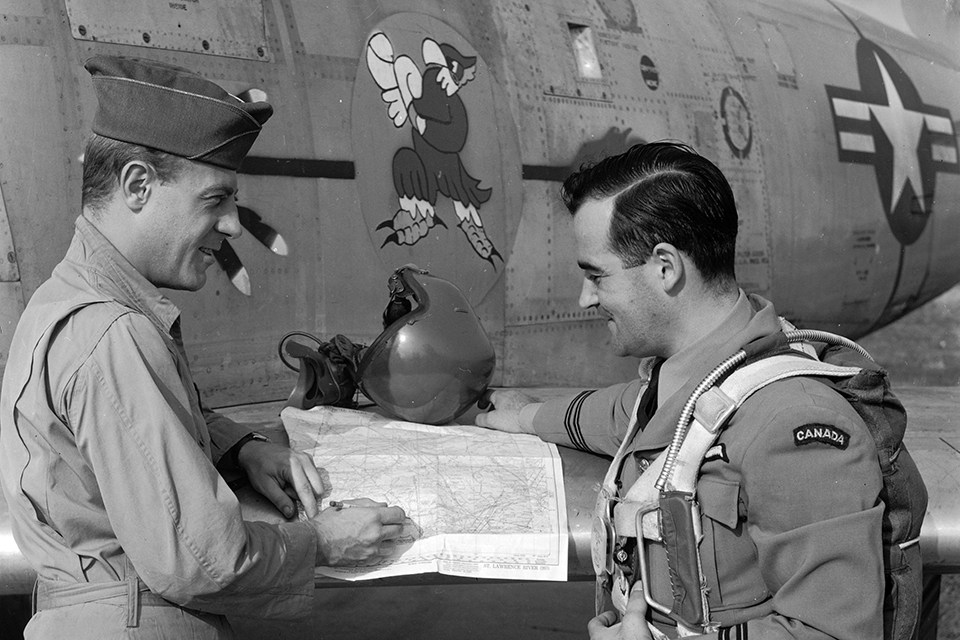

In May 1950, Levesque was stationed at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia, training on the new North American F-86A Sabrejet fighter. The following month, on June 25, the Cold War erupted into full-scale conflict in Korea, and the Canadian ace would soon find himself in the thick of the fighting.

On June 27, U.S. North American F-82G Twin Mustangs, flying from Japan, fought their first air battle with the small North Korean air force and made their first kill: a Russian-made Yakovlev Yak-11 (see “First Blood in Korean Skies,” September 2009 issue). By June 29, Douglas B-26 Intruder medium bombers and Boeing B-29 Superfortresses had joined the action, as had Lockheed F-80C Shooting Star jet fighters. On July 3, Grumman F9F Panther jets and Douglas AD Skyraider dive bombers began slamming enemy positions and supply lines.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

At first the thrown-together collection of mostly obsolescent planes seemed sufficient to handle this new air war, quickly decimating the North Korean air force. But the Americans got an unwelcome surprise on November 1 when five Mikoyan Gurevich MiG-15s attacked a flight of North American F-51 Mustangs. The enemy jets were flown by Soviet pilots based in Manchuria who were secretly aiding the North Koreans. One week later the world’s first all-jet air battle took place between the aging American Shooting Stars and Soviet MiG-15s. Although one MiG was claimed, it became obvious that the newer sweptwing MiG-15s outclassed the older Shooting Stars, which couldn’t adequately protect the B-29s. As Superfortress losses mounted, President Harry Truman ordered an F-86A Sabrejet frontline unit, the 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, to Korea.

In December 1950, Levesque—now a flight lieutenant—arrived in Korea with the first Sabrejets. He would become the first Canadian to fly air combat missions in the Korean War. The Sabre impressed Levesque: “It was like being on a bucking bronco—I didn’t ride it, I just hung on! It had lots of power and could turn on a dime. When you pull back you get a whole lot of air—the stabilizer doesn’t fight the elevator. This made the aircraft tremendous.” He earned the U.S. Air Medal for flying 20 missions between December 17 and December 21, 1950, inclusive, an average of four missions a day.

On March 31, 1951, Levesque was with two squadrons of Sabres protecting a large flight of B-29s attacking the bridges spanning the Yalu River, the boundary between North Korea and its Communist Chinese ally. He was flying as wingman to Major E.C. Fletcher when suddenly the squad leader called out that bandits were coming from the right. The Sabres dropped their auxiliary fuel tanks as two additional MiGs were spotted at 9 o’clock, “off our left wings and above us a bit.” Levesque’s flight turned toward these two enemy planes, which separated and banked away to evade the pursuing Sabres.

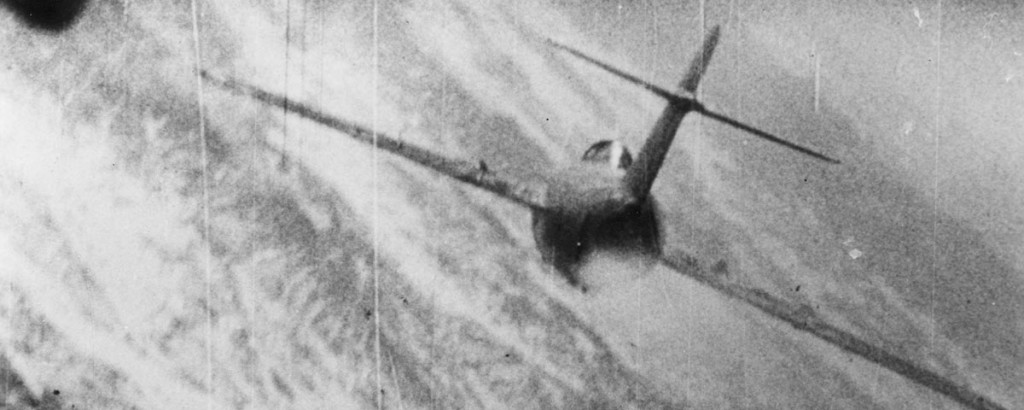

Levesque later reported: “My MiG pulled up into the sun, probably trying to lose me in the glare. This was an old trick the Germans used to like to do—but this day I had dark sunglasses on, and I kept the MiG in sight.” The MiG leveled off, likely not realizing Levesque was still on his tail. The Canadian adjusted his illuminated gunsight for deflection shooting and banked steeply to turn inside the MiG, triggering a twisting dogfight that quickly spiraled down from 40,000 feet to 17,000 feet. Levesque was about 1,500 feet from the MiG when he opened fire. His aim was good: Six streams of .50-caliber bullets smashed into the MiG, which rolled violently to the right and continued rolling until it crashed into the ground.

“I started to pull up, and saw another MiG diving from above me,” he continued. “I climbed into the sun at full throttle and started doing barrel rolls. The MiG disappeared.” His combat with the MiGs concluded, Levesque faced another danger, this time from friendly fire: “I went right through the B-29 formation and they all shot at me! Thank God they missed. I waggled my wings and they stopped firing, but lots of shells had just missed me.”

Levesque suddenly realized that his fuel was approaching “bingo,” the point where he had just enough to get him back to base at Suwon, South Korea. As he headed home, alone with his thoughts, he could take pride in the fact that he was at last an ace.

Omer Levesque was awarded the U.S. Distinguished Flying Cross for his role in the March 31 battle. He would complete 71 operational sorties with the 334th FIS before being sent home in June 1951.

In addition to his other decorations, Levesque received the Queen’s Coronation Medal in 1953. Following a variety of peacetime assignments, he retired from the RCAF in 1965. Inducted into the Quebec Air and Space Hall of Fame, he served on the Canadian government’s Air Transport Committee for 22 years, until 1987. Levesque died in June 2006, at age 86.

Herb Kugel, who writes from Nova Scotia, Canada, has been a contributing editor to two aviation magazines. For additional reading, he recommends: All the Fine Young Eagles: In the Cockpit With Canada’s Second World War Fighter Pilots, by David L. Bashow; The Royal Canadian Air Force at War 1939- 1945, by Larry Milberry and Hugh Halliday; and Air Aces: The Lives and Times of Twelve Canadian Fighter Pilots, by Dan McCaffery. Also see Miles Constable’s Canadian Air Aces and Heroes Web site at www.constable.ca/caah.

Originally published in the May 2010 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.