By early 1945 it seemed obvious to the Allies that Japan would never surrender and the only way to achieve total victory in the Pacific War was by invasion. This grim prospect — and the need to win air superiority over Japan — led to the U.S. military’s request for a long-range fighter to escort Boeing B-29s to the Home Islands. Allied planners anticipated that the Japanese would send up hundreds of suicide planes to take out the B-29s, so the bombers had to have ample fighter protection.

The only aircraft capable of meeting that demand as of February 1945 was the North American P-51D Mustang. Carrying external fuel tanks, it could take off from newly captured airfields on Iwo Jima and make the nearly 1,500-mile round trip (see “Sun Setters Over Japan”). But the Mustang didn’t have the legs to spend much time over Japan with the bombers, and pilot fatigue during the 7½-hour missions was also a factor. What the U.S. Army Air Forces really needed was a long-range fighter that carried two pilots, able to stay with the B-29s throughout the mission and preferably launch from the same base as the bombers (Guam).

Two designs fit the bill: Northrop’s P-61E two-place fighter and the North American P-82 Twin Mustang, the last piston-engine fighter ordered into production by the USAAF. Although developed from the P-51 and to outward appearances two Mustangs joined by a center wing and horizontal stabilizer, the Twin Mustang was in fact an entirely new design. Its longer fuselages accommodated additional fuel tanks, which along with external tanks gave the P-82 a range in excess of 2,000 miles. Six .50-caliber machine guns were mounted in the center wing section for concentrated firepower, and its strengthened outer wings had hardpoints for carrying drop tanks or ordnance. In spite of its double fuselage configuration, the Twin Mustang was fast and surprisingly maneuverable.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

World War II ends

When the atomic bomb brought the war to an abrupt end, the P-82E was still in production and had yet to reach the Pacific theater. While many contracts for prop fighters were canceled in September 1945, the Twin Mustang wasn’t among them. It continued in production and was converted into an all-weather fighter that would replace the P-61 Black Widow. Strategic Air Command used the Twin Mustang as a long-range escort for the Convair B-36, as it was the only prop fighter that could keep up with the giant bomber.

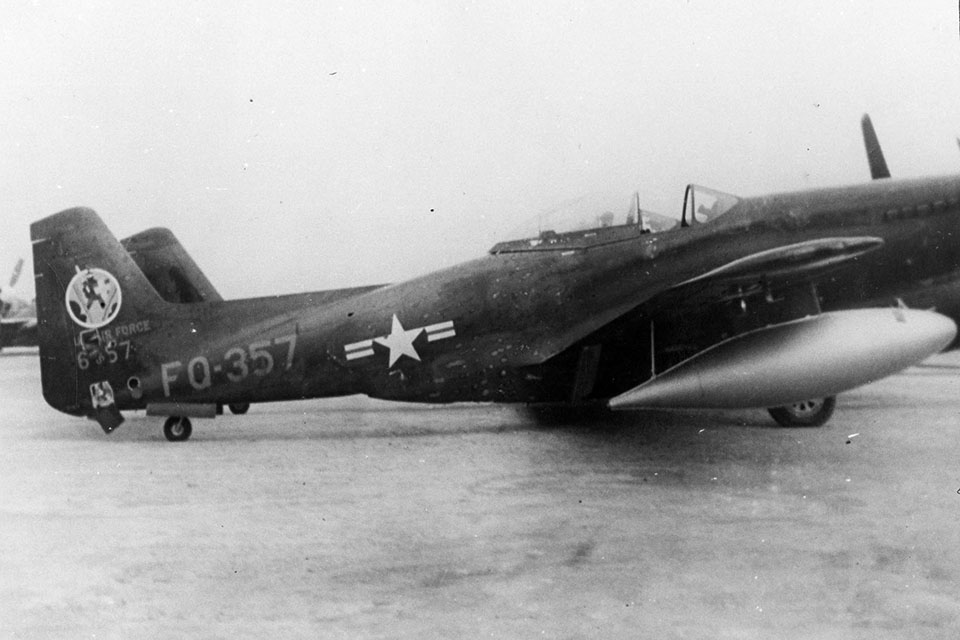

Air bases in Japan and Okinawa were among the first to receive the P-82. By 1948, the war-weary F-61 Black Widows, as the newly formed U.S. Air Force had redesignated them, were experiencing heavy maintenance problems due to a lack of spare parts and were about ready for the scrapheap. But they had to hang on until the new all-weather Twin Mustangs arrived. The 4th Fighter Squadron (All Weather) on Okinawa and the two all-weather fighter squadrons in Japan (the 68th and 339th) would receive their F-82Gs in mid-1949.

Some drastic modifications had been made to the radar-equipped all-weather models. The right cockpit now housed a radar operator with his scope rather than a second pilot. A huge radar pod, projecting in front of the propellers to prevent signal interference, was mounted under the wing between the two fuselages.

A New War

When the North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel on June 25, 1950, starting the Korean War, the three F-82G squadrons in the Far East were fully equipped and ready for action. However, at the time the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star jet, which had replaced the F-51D Mustang, was the fighter of choice for the Far East Air Force.

The rapid advance of the North Korean People’s Army created a critical situation in Seoul. There were many American civilians in the South Korean capital who had to be evacuated immediately. What few airfields South Korea possessed were left over from the Japanese occupation, and there had seemed no reason to improve them. This meant the F-80s had to launch and recover from bases in Japan, which gave them very little loiter time over Seoul. The only available aircraft with long-range capabilities was the F-82G.

Accurate intelligence on the North Korean air force was skimpy, but it was known that the Soviets had given them a large number of World War II–vintage Yak and Lavochkin fighters, as well as some Ilyushin Il-10 ground attack planes. If these aircraft ventured south of the 38th parallel, they could threaten the evacuation of civilians, so it was crucial to have air cover for the Douglas C-54 transports sent in from Japan for that purpose.

The 68th Squadron was stationed near Fukuoka, Japan, at Itazuke Air Base, the closest base to the Korean Peninsula. Its complement of Twin Mustangs was not enough to handle the job, so a significant number of F-82s from the 339th out of Johnson Air Base at Iruma, Japan, and the 4th out of Naha Air Base on Okinawa were brought in to fly combat missions during the war’s early days. At the time the inventory of F-82s in theater totaled 35, and 27 answered the call. The remainder had to stay behind to stand alert at their assigned bases.

Engage in more Mustangs and More Korean War Tales

First Flight

On the night of June 25, F-82G pilot Lieutenant George Deans and his radar observer (R/O), Lieutenant Marvin Olsen, flew the Korean War’s first accredited armed combat mission. With the war only hours old, the 68th Squadron had a couple of its aircraft sitting ready on the alert pad. “We had been moved quickly from our detachment’s base at Ashiya over to Itazuke,” Lieutenant Deans remembered. “The weather over South Korea and the Sea of Japan was bad, and one of our radar sites picked up an ‘unknown’ coming in from South Korea headed straight for Kyushu. We were alerted and scrambled to intercept. Fortunately, it was not hostile, but we were armed just in case. The unknown was an SB-17 from the 3rd Air Rescue Squadron out of Ashiya Air Base. Early the following morning, we paired up with Lieutenant William ‘Skeeter’ Hudson and his R/O for the first combat air patrol over the Inchon area. It was still overcast with ceiling slightly below 3,000 feet. Our main objective was to patrol the main evacuation road between Seoul and Inchon.”

On the 26th, Twin Mustangs swept the sky over Seoul in a wide circle in case of trouble. A few North Korean aircraft showed up, evidently figuring the airport would be unprotected by fighters, but they didn’t try to penetrate the cover. A Yak fired on and missed one of the 68th Squadron’s F-82s, but the Twin Mustang made no effort to pursue the fleeing enemy fighter for fear of leaving a gap in the coverage.

The Il-10s — escorted by Yak-9s, Yak-11s and La-7s — were out in force on June 27 and 29, attempting to bomb the airfield at Kimpo and Seoul City Airport. F-80s and F-82s patrolling the area dominated the big aerial battles that ensued. USAF pilots scored seven confirmed victories on the 27th and five on the 29th, with no American losses on either day. Twin Mustangs made the first three kills of the war: a Yak-11 and a pair of La-7s.

Things were relatively quiet well into the Twin Mustangs’ patrol on the 27th. But at noon five North Korean fighters attacked the trailing F-82 in a flight of four. The pilot, Lieutenant Charlie Moran, spotted his attackers just as one was firing, and he took violent evasive action, though not in time to avoid a hail of lead that ripped into one of his vertical stabilizers. All four Twin Mustangs dropped their external fuel tanks to reduce drag.

Firsthand Account

Over the next few minutes, the F-82Gs made their mark in the record book. Skeeter Hudson and his R/O, Lieutenant Carl Fraser, banked in a high-G turn to get behind the attacking Yak-11.

“Our mission was to protect the evacuation at Kimpo Air Base,” said Fraser. “There was fighting on the ground just north of the city, but our job was to stop any air interference against the C-47s and C-54s that were busy landing and taking off below us. We saw that Lieutenant Moran was being fired on and pulled in right behind the attacker. Those five hostiles were trying to attack the transports as they were taking off.

“Before the Yak pilot could react, we were locked on his tail, so he pulled nose up into the clouds. But it was too late because we were so close to him. We kept a visual on him while climbing through the soup. We fired a good burst with all six guns, and they found their mark as pieces of the Yak’s stabilizer and fuselage were blown off and we avoided them as they flew past us. At that time, the pilot racked his fighter over into a steep turn to the right, with us staying clamped onto his tail. Lieutenant Hudson fired another burst that impacted all over the Yak’s right wing, which set one of his gas tanks on fire. Two seconds later, its right flap and aileron flew off and they barely missed us, and we were so close both of our aircraft almost collided.

“I could clearly see the pilot turn around and say something to his rear seat observer,” continued Fraser. “He then pushed his canopy back, stepped out on the wing and again said something to his backseater. It was my impression that he [the backseater] was severely wounded or dead at that time because he never made an effort to exit the stricken fighter. The pilot pulled his ripcord and the chute opened, dragging him off the wing when it opened. Most of the encounter had been below 1,000 feet. We did a quick 180 to see where the pilot had landed. His chute was in the middle of a large group of South Korean soldiers. I figured the pilot had surrendered, but I later found out from a South Korean major that the pilot had started shooting at his men and they returned fire, killing him. At the time we were circling the downed pilot, Lieutenant Moran was shooting down an La-7 over Kimpo airfield.”

Both victories were scored within sight of Kimpo, thus having instant confirmation without the need to rely on gun camera film. Within minutes of Moran’s kill Major James Little, the 339th Squadron CO, locked onto another La-7 and fired a long burst, sending it earthward. All of these encounters were at low altitude, leaving very little room for error. Little made his kill north of Kimpo, and it was not witnessed from the ground, so his confirmation came later.

Yak Attack

In action farther north, two more F-82s from the 339th encountered North Korean fighters. Captain David Trexler and his wingman, Lieutenant Walter Hayhurst, had their hands full for a few minutes with several Yaks. “My wingman and I attacked the closest Yak, who immediately broke hard to the left, which put him directly in front of me,” Trexler recalled. “As I closed to about 3,000 feet, I fired a short burst, causing the pilot to initiate a sudden right turn with his nose pointed down. At that point I continued to track him perfectly while firing a second burst. He reversed his turn again while I pumped a third burst of .50-caliber into his aircraft. Now the distance was down to less than 1,000 feet. Both of our aircraft were at full throttle and pointed down, which put us at an IAS [indicated airspeed] of 425 mph.

“My rounds were now causing some trouble for the Yak as its pilot rolled left into an inverted position and dropped down into the cloud layer below. I immediately pulled up because there were some mountains jutting through the clouds. Since we never saw him hit the ground or bail out, we were credited with a probable. When the day was over, our F-82s were credited with three confirmed kills, but many of our pilots claimed they scored numerous hits….Chances are, there were several more kills made by us, but with the heavy cloud layer we were never able to follow them down and see them crash.”

The three F-82 squadrons were responsible for covering a large area, and thus were well represented during the June 27 aerial battles. The F-80s flying out of Itazuke, which were credited with four victories that day, had to work their shifts in relays because the Shooting Stars’ thirsty jet engines did not allow much time over Kimpo.

It didn’t take long for North Korean fighters to back off because of the numbers of F-82s and F-80s they faced. But the Twin Mustangs’ days of dogfighting glory were numbered in what would soon become a jet-versus-jet air war. Tasked with close air support and armed recon missions far to the north, they would prove to be the ultimate stopgap fighter-bombers during the August-September period that led to the successful defense of, and breakout from, the Pusan Perimeter.

Days of Glory

Although the 4th Squadron’s tenure in the war was short-lived, its aircrews saw plenty of action during that brief time. Lieutenant Colonel John Sharp, the 4th’s CO, also headed up the temporary composite group that combined all three F-82 squadrons. He took part in a night mission on July 4, 1950, that sadly involved the first loss of a USAF aircrew. Sharp recalled: “Since June 25, the North Koreans were rolling southward practically unopposed, and the low cloud cover had kept us guessing as to how many and how far they had advanced. On this night, I sent out two of our F-82s to watch for any breaks in the clouds so we could get down and report enemy ground activity.

“Captains Warren Foley and Ernest Fiebelkorn remained on station for several hours without a break. As a last resort, Captain Fiebelkorn told Foley that he was going to try and get below the clouds. Minutes later, radio contact was lost with his F-82. As Captain Foley’s fuel reached ‘bingo,’ he returned to Itazuke and he stated that he thought his wingman had gone in, and we later found out that it was exactly as he had figured. As a first lieutenant, Fiebelkorn was one of the top-scoring aces with the 20th Fighter Group in World War II [9.5 kills]. Captain Foley stated that they believed the clouds were beginning to break up, and with this information I called armament and told them to load one of our aircraft with eight 5-inch rockets.”

Lieutenant Colonel Sharp took off at midnight. Sure enough, the clouds were breaking up over South Korea, so he could see the roads were jammed with vehicles—presumably enemy trucks—that were 20 miles south of the bomb line, indicating the North Koreans had advanced much farther than anticipated. He and his R/O, Sergeant George Umbarger, agreed that hitting the trucks that far from the front lines was asking for trouble because they might be friendlies. Sharp and Umbarger decided instead to head north with their ordnance.

“We finally got into an area that I knew had to be held by the enemy,” Sharp continued. “The first target we hit caused a secondary explosion that lit up half of Korea. A little farther north, I noticed a speeding vehicle with its lights on high beam moving south. It had to be a staff car trying to catch up to the war! I deliberately took aim on the rocket ladder [a gunsight aiming device], cranked in a little ‘Kentucky windage’ to lead him, snapped my eyes closed and cut loose with two of my 5-inch rockets. Seconds later…BLAM! Both rockets impacted right at the base of the vehicle and its lights went dark. It was the best rocket shot I ever made!”

Ground Slog

July was a dismal month for UN ground forces. August would see no improvement except for the huge buildup of aircraft that eventually contributed to the collapse of the North Korean People’s Army. By then the 68th was the only F-82 squadron left in the war, and it was spread thin carrying out multiple assignments. On the morning of August 7, tragedy struck again when Lieutenant Charlie Moran, the pilot who had scored the second kill of the war, took off with R/O Lieu tenant Francis Meyer at 0300 hours on a routine interdiction mission and disappeared without a trace or any radio transmission.

Thanks to the successful amphibious landing at Inchon in mid-September, UN ground forces broke out of the Pusan Perimeter. As they advanced north, friendly troops found the wreckage of Moran’s Twin Mustang in a valley near a severed cable that had been strung from ridge to ridge. Moran had evidently spotted movement on the valley road and come down to attack when his plane hit the cable. This hazard would plague several F-51 Mustangs in the coming months during flights at first or last light, when the cables were hard to see.

During the F-82’s glory days in Korea (July 1950 through 1951), aerial refueling was not an option for the numerous fighter-bomber types that were flying missions over North Korea, limiting their range. The big Twin Mustang, in contrast, could take off from Itazuke with a full load of ordnance and range all the way to the Yalu River in search of targets. If an F-82 happened to lose an engine, it could still hit its target and return safely to base.

Endurance Test

The final weeks of 1950 saw the F-82 tasked with long-range weather reconnaissance over the North. One of the 68th Squadron pilots, Lieutenant R.K. Bobo, gave an example of the Twin Mustang’s stamina during those lengthy missions: “The weather reconnaissance sorties we flew were, in most cases, an exercise in boredom. Sometimes we were ordered to look at a specific target area. But most of the time we were tasked with evaluating weather conditions over a wide area that the fighter-bombers were going to hit later in the day. On these missions, we carried a full load of .50-caliber ammunition and drop tanks to give us extended range. On one memorable mission, we took off to cover an area all along the Yalu River up in the northwest corner. From there, we would fly due east, staying just south of the river. All of North Korea was under heavy cloud cover and the river was frozen over, which made our radar almost useless since we depended on it to show the difference between open water and land. Also, we were fighting high winds. My R/O estimated the time it would take to hit the east coast and the Sea of Japan.

“We flew for a very long time without hitting the coastline. When we finally made it, we made a quick turn and headed south and began trying to contact the DF station at Wonsan asking for a fix. With our fuel running low from our long flight, we had to recover at Kimpo Air Base. Once on the ground, we started computing our time in the air and the distance we had flown to the east. Our figures showed we must have been right over Vladivostok before turning south! The Russians had to be tracking us on radar and figured we were no threat. If they had, we would have been in serious trouble.”

By the end of 1951, only eight F-82s were operational with the 68th, as the demand for their services had greatly diminished. March 1952 was the final month of operations for the big long-range prop plane, which had bridged the gap between the retirement of the old P-61 Black Widows and the arrival of the new all-weather jet fighters. In the process, it had made a significant contribution to the Cold War’s first major conflict, and earned a lasting place in the annals of air combat.

Warren Thompson specializes in military aviation from 1937 to the present. He recommends for further reading “Double Menace,” by David R. McLaren, and “The Korean Air War,” which he co-authored with Robert F. Dorr.

Click here and build a replica of Hudson and Frazier’s F-82G.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.