Sunday afternoon, May 20, 1951. Fourteen North American F-86A Sabre fighter jets from the 335th Fighter Interceptor Squadron lifted off from Suwon Air Base, South Korea, in response to a call for help from U.S. Air Force fighters under attack by Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 jet fighters near the Yalu River, separating Korea and China. Flying in the second flight of the relief force was 27-year-old Captain James Jabara. He had already claimed four of the MiGs–he needed one more to become the first Korean War ace.

‘Jabara stood out among his group of fighter pilots almost as much as if he really had been a knight of yore on a quest for the Grail,’ wrote Wichita State University professor Craig Miner of the Oklahoma native who grew up in Wichita, Kan. ‘War provides many opportunities for the exercise of heroic courage; air war creates added speed and intensity; and air war was James Jabara’s chosen situation.’

The son of Lebanese immigrant John Jabara, James was born on October 10, 1923, in Muskogee, Okla. Soon after his birth, Jabara’s family moved to Wichita, where John Jabara opened a grocery store. Young Jabara helped in his father’s store while dreaming of loftier things. ‘I used to read articles about [Eddie] Rickenbacker and all these novels you read about air combat,’ he recalled, ‘and I guess from the sixth grade it was my ambition to be a fighter pilot.’

In May 1942, after graduating from Wichita’s North High School, Jabara enlisted in the aviation cadet program at Fort Riley, Kan. In October 1943, he received his pilot’s wings and a commission as second lieutenant in the United States Army Air Forces at Moore Field, Texas.

In January 1944, Jabara was sent to the 363rd Fighter Group of the Ninth Air Force, stationed in England. Flying North American P-51 Mustang fighters, his first mission was attacking railroad targets in German-occupied Belgium.

In March 1944, Jabara was escorting American bombers to a target in Germany when his flight of four P-51 Mustangs was bounced by 50 Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighters. During the dogfight Jabara’s canopy was shot off. Unhurt, Jabara went after one German and shot him down. ‘After I shot this guy down I figured I’d better get out of there,’ Jabara wrote. ‘I was all by myself, I was freezing…I guess the temperature was 35 degrees below zero.’

‘I had to fly around 10,000 feet,’ Jabara said, ‘and I’d never seen so much flak in all my life…I didn’t know whether to jump…or try to get back to England.’ He stayed in his Mustang and made it safely back to the 363rd’s base.

Jabara flew fighter-bomber missions over France and the Low Countries until October 1944, when he was sent back to the United States. He returned to combat in Europe in February 1945, again flying P-51s, and flew a total of 108 missions, during which he was credited with shooting down 1 1/2 German planes. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross with one Oak Leaf Cluster and the Air Medal with 18 Oak Leaf Clusters for bravery.

He returned to the United States in January 1946 and considered leaving the Air Force to attend college. ‘In fact, I was just ready to get out when the Air Force offered me a regular commission,’ he recalled. ‘So I accepted.’

Jabara attended the Tactical Air School at Tyndall Air Force Base, Fla., during the rest of 1946. After finishing in 1947, he volunteered for duty with the 53rd Fighter Group, stationed on Okinawa, where he worked in the group’s personnel department.

Jabara did not make his first jet flight until 1948, when he took the controls of a Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star jet fighter. ‘It was entirely different,’ Jabara recalled. ‘I was at 10,000 feet before I remembered to raise my landing gear….It was so quiet and fast….I guess that was probably the happiest moment of my life.’

Jabara returned to the United States in 1949 and joined the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing at Langley Field, Va. While he was at Langley, he got to fly the Air Force’s first sweptwing fighter, the F-86, which came into service in 1949.

Jabara flew the F-86 in the United States for more than a year, including a tour of duty at New Castle County Airport in Delaware as a flight leader. Then on June 25, 1950, the Korean War began.

On November 1, 1950, six sweptwing MiG-15 jet fighters attacked a flight of American P-51 Mustangs patrolling over the Yalu River. Alert flying by the Mustang pilots–and poor marksmanship by the MiG pilots–allowed the P-51s to escape. On November 8, Chinese-flown MiG-15s attacked U.S. Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers during a bombing raid over North Korea.

The only American fighter that could match the Russian-built MiG-15 was the F-86 Sabre. In December 1950, F-86A Sabres of the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing arrived at Kimpo Airfield near Seoul, South Korea, ready for action.

James Jabara arrived with the 4th Fighter Wing on December 13 and was assigned to the 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron. Jabara joined other 334th Squadron pilots patrolling the 100-mile-wide strip of airspace south of the Yalu River known as ‘MiG Alley.’

By the end of December 1950, the 4th Fighter Wing’s Sabres had run up a spectacular kill ratio of 8-to-1 over the MiGs. Then the 4th Wing’s Sabres were forced back to Japan by the Chinese winter offensive of January 1951, during which Kimpo Airfield was overrun. The distance from Japan to MiG Alley was beyond the Sabre’s range and put a brief stop to patrols over the Yalu. In March, after U.N. ground troops drove the Chinese back over the 38th parallel, the 4th Wing returned to South Korea, resuming its patrols from Suwon Air Base, 20 miles south of Seoul.

By April, Jabara had damaged one MiG-15 in combat. ‘I’ve always felt that the MiG was a better airplane above 30,000 feet, which was where most of our fighting was,’ Jabara later said. ‘The F-86 was a better airplane below 30,000 feet. As a fighting machine, we had better gunsights. Our airplanes were a little sturdier built.’

On April 3, Jabara took off with 12 334th Sabres from Suwon and soon sighted a flight of 12 MiG-15s flying on the Chinese side of the Yalu–where the American aircraft were forbidden to fly. When the MiGs crossed over the Yalu into Korean airspace, Jabara and the other 11 Sabres in the patrol attacked them. ‘It wasn’t much of a problem: I latched onto the number 10 man in that flight and he made a big turn trying to go back to the Yalu River.’ Jabara got onto the MiG’s tail and fired his six .50-caliber machine guns. ‘He was at low altitude and I was able to really clobber him….He went right into the ground.’

Jabara’s success brought him to the attention of Colonel John C. Meyer, commander of the 4th Fighter Wing. Meyer, who had been credited with 24 German aircraft while flying Mustangs in World War II and who would add two MiGs to his score while flying the F-86, regarded Jabara as having ‘the characteristics and desire, and also having a start on the count’ to become an ace.

Colonel Meyer said as much to Lt. Gen. Earle E. Partridge, commander of the Fifth Air Force. ‘So he said, ‘Stick him out in front and see what you can do,” Meyer recalled. ‘So we started….Anything that was a milk run, he didn’t go; anything that was up the Yalu, he did go….It didn’t take very long for him to get the other three.’ On April 10, Jabara downed another MiG-15 over MiG Alley. Two days later on April 12 he claimed a third. Then, on April 22, Jabara shot down his fourth MiG-15.

In early May, the 334th Squadron was rotated back to Japan. Not wanting to leave Korea before scoring his fifth kill, Jabara had himself transferred to the 335th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, a fresh unit replacing the 334th.

May 20, 1951, was a day of good flying weather. Around 1700 hours, a call for help came over the radio from a Sabre patrol near Siniju in northwest Korea. They were under attack by MiGs.

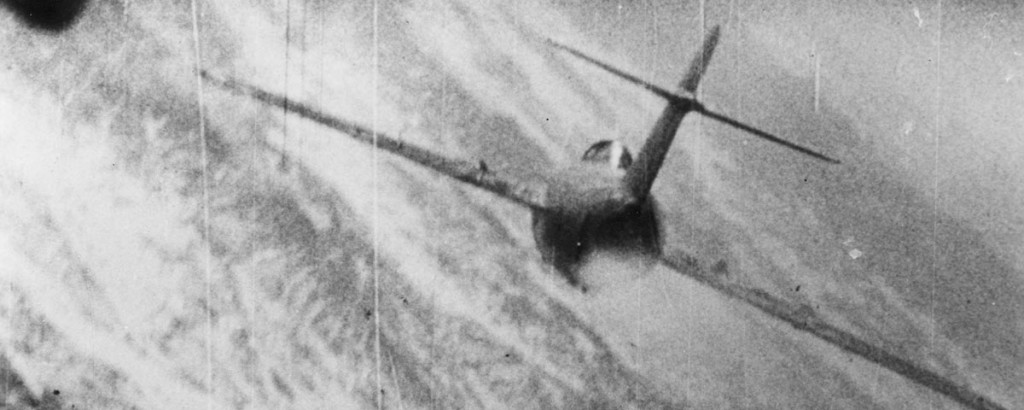

Jabara took off with the second flight of seven F-86s, led by Captain James Roberts. Once airborne, Jabara was joined by his wingman, Lieutenant Salvadore Kemp, and flew north toward MiG Alley. As the 335th’s flight approached the battle area over the Yalu from the China Sea, Jabara looked up and sighted 30 MiG-15s flying above his flight. The MiGs peeled off to attack the newcomers.

Seeing that, Roberts ordered his flight to drop their wing tanks. When Jabara pulled the lever to release his drop tanks, he felt the Sabre roll to one side. He had to grab the control stick in both hands to keep the airplane under control. One of the wing tanks had failed to release and was still attached to his Sabre’s wing.

‘Orders were that if you had a hung tank, you were to beat it for home,’ Jabara later said. But he was not about to give up what might be his last shot at acedom. ‘I called my wingman and told him that we were joining the fight.’ Followed by Kemp, Jabara pulled his Sabre steeply up. He spotted three MiGs and made a firing pass at them. Three other MiGs attacked from above and behind. Jabara turned to face his new attackers, and two of the MiGs broke away.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Jabara latched onto the third MiG. ‘He tried everything in the book–diving and turning–to get rid of me,’ Jabara said, ‘but he couldn’t.’ Jabara closed to within 1,500 yards of the MiG’s tail and fired three bursts from his machine guns, hitting the MiG’s fuselage and left wing. ‘He did two violent snap rolls and started to spin down,’ Jabara remembered. The MiG spun from 27,000 feet to 10,000, with Jabara and Kemp following him. At 10,000 feet the pilot bailed out; seconds later, the MiG-15 disintegrated. ‘All I could see was a whirl of fire,’ Jabara remembered.

Jabara and Kemp climbed back up to rejoin the fight. When he reached 20,000 feet, Jabara noticed that Kemp was not with him, having tangled with some MiGs on the way up. Jabara then spotted six MiG-15s. Without hesitation, he attacked the sixth MiG in the flight. The MiG burst into flames and began to spin. Jabara overshot the MiG, pulled back his throttle and popped out his speed brakes to slow down quickly and stay with the MiG.

‘I circled him outside his spiral and followed him down to about 6,500 feet to be sure he hit the ground,’ Jabara wrote. Unseen by Jabara, however, two MiGs had come up behind him and opened fire. Jabara closed his speed brakes, shoved his throttle forward and broke hard left. The MiGs followed him. ‘For about two minutes we went around and around,’ Jabara recalled. ‘They were shooting at me while I tried my best to get away.’

Then Jabara heard two of his friends, Morris Pitts and Gene Holley, talking over the radio. ‘There’s an F-86 being shot at down there,’ Pitts said.

‘Roger,’ Jabara radioed back. ‘I know it only too damned well.’

Pitts and Holley swooped down to help Jabara. The lead MiG’s wingman, seeing the approaching Sabres, turned tail and ran. Holley got on the other MiG’s tail, radioed Jabara to hold steady, then opened fire while Pitts protected Holley’s tail. After six .50-caliber bursts from Holley, the MiG-15 began smoking and broke off, but the Sabres did not have enough fuel to go after him. Jabara, Pitts and Holley formed up and started south. ‘Thanks for saving my neck,’ Jabara radioed Holley.

The fight near Siniju had lasted only 20 minutes, with 34 Sabres battling 50 MiG-15s. The Sabres scored two kills–both by Jabara–and one probable.

‘On the way back I was so low on fuel that I had to shut my engine off and glide,’ Jabara remembered. ‘Then, before I got back to the air base, I started the engine back up and landed.’

The three pilots landed back at Suwon and taxied up to the parking area. To the cheers of his ground crew, Jabara calmly shoved back his Sabre’s cockpit canopy, removed his oxygen mask, and–like after every other mission–pushed a cigar into his mouth. Only then did he climb down and let Roberts and Kemp hoist him on their shoulders and carry him around the field.

The 335th’s pilots threw a party in his honor. During the festivities, Jabara used his hands to demonstrate how he shot down the MiGs, not forgetting his narrow escape after losing his wingman. ‘I made a bad mistake today. Never do what I did,’ he warned the others. ‘Never go after a MiG if you haven’t got your wingman there to cover you. When you’ve got your eye glued to that sight, you’re a sitting duck.’

The next day, Monday, May 21, 1951, Jabara was relieved of combat duty with the 335th. On May 22, before a group of senior Air Force officers in Tokyo, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross by General Partridge.

Recommended for you

Jabara soon returned to the States and was sent on a publicity tour as the U.S. Air Force’s first Korean War air hero. Films of his F-86 in Korea were shown on every movie newsreel. A song, ‘That Jabara Bird,’ was written about him, and his receiving of the Distinguished Service Cross was re-enacted at a baseball game in Boston. Back home, he and his father were featured on local and national radio and television shows, and Wichita held one of the best-attended parades in the city’s history for a returning son.

Following his publicity tour, Jabara was transferred to the Air Training Command at Scott Air Force Base, Ill., where he helped train stateside fighter pilots through the rest of 1951 and 1952.

While the war continued in Korea, Jabara began asking his superiors to let him return to combat. ‘I just wanna go out and do some more shootin’,’ Jabara said. He had only flown 63 missions of his 100-mission tour of duty and was uncomfortable behind a desk.

In December 1952, the Air Force granted Major Jabara’s request for a second tour, and he returned to Korea in January 1953. He was again assigned to the 4th Fighter Wing, now commanded by Colonel James K. Johnson and equipped with an improved version of the Sabre, the F-86F. During the early part of 1953, Jabara flew support missions and patrols into MiG Alley with his old squadron, the 334th, often flying two missions a day.

During March and April 1953, while other Sabre pilots shot down 27 MiG-15s, and four F-86Fs were lost, Jabara did not shoot down any MiGs. Finally, on May 16, 1953, Jabara scored his seventh MiG kill. On May 26, he was leading four Sabres from the 334th on a patrol over MiG Alley when he sighted 16 MiG-15s crossing the Yalu. Punching off his wing tanks, Jabara led his Sabres through the center of the enemy flight. Surprised by the sudden attack, the MiGs scattered and hurried back across the river. A few minutes later, Jabara’s flight sighted two more MiGs and attacked. Jabara shot both down.

On June 10, in a single mission, Jabara forced down one MiG-15 and blasted another out of the sky.

On June 18, Jabara’s Sabre flight and the F-86F fighter-bombers they were escorting were harassed by MiGs attacking from out of the clouds. Jabara’s wingman noticed a flight of four MiG-15s, which ducked into the clouds. The two pilots went after them. Just as Jabara was about to fire on his MiG, he felt a ‘big explosion’ in his Sabre. ‘I pulled up into the overcast, trying to figure out what happened.’ Jabara quickly found that the problem had been his air conditioner: ‘It didn’t blow up on me, but it had been clogged up and let go all of a sudden.’

Jabara guided his Sabre back down. Breaking out of the overcast, he saw a hill right in front of him. ‘I thought I had had it.’ He missed the hill and climbed back up through the clouds. He and his wingman then sighted another flight of six MiGs and went after them. Jabara singled out a damaged MiG-15 in the flight and shot him down.

On June 30, 1953, Jabara had his best day. On a mission that morning, he downed a MiG-15. That afternoon he was on a second mission, escorting F-86F fighter-bombers, when they were attacked by large numbers of MiG-15s.

Jabara and his flight attacked six MiGs; he closed on the sixth MiG and hit him in the tail section. The MiG burst into flames, forcing the pilot to eject. ‘All of a sudden my wingman started screaming to me to break,’ Jabara recalled, ‘…there were other MiGs coming in on us; they were shooting at us.’

Jabara shoved the Sabre’s throttle forward ‘to get power and speed as fast as I could.’ Instead, his Sabre’s jet engine flamed out. At 20,000 feet, Jabara started to glide his Sabre toward the ocean, ‘where I could bail out if I couldn’t get the thing started and maybe be picked up by one of our helicopters or air-sea rescue boats.’ He was eventually able to get the Sabre’s engine restarted, however, and returned to Suwon Air Base.

For Jabara and other Sabre pilots, June 1953 was their greatest month. The Sabres sighted 1,268 MiGs, engaged 507 and destroyed 77.

Late on the afternoon of July 15, Jabara shot down his 15th MiG-15, making him a triple ace and the second-highest-scoring jet ace in Korea, next to Captain Joseph McConnell, who scored 16 MiG kills.

In all, Jabara flew 163 missions during his two tours of duty in Korea. Despite his many encounters with MiGs, Jabara was never wounded over Korea, nor were any of the Sabres he flew there damaged. In addition to his earlier decorations, Jabara received an Oak Leaf Cluster to his Distinguished Service Cross and a second Distinguished Flying Cross for bravery.

In late July 1953, after completing his second Korean tour, Jabara returned to the United States. In August he was sent to Yuma, Ariz., for duty with the 4750th Training Squadron. In January 1957, Jabara was with the 3243rd Test Group at Eglin Air Force Base, Fla., where he flew Lockheed F-104 Starfighters. In February 1958, Jabara joined the 337th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Westover Air Force Base, Mass., again flying F-104s.

In August 1958, during the Quemoy and Matsu crisis with Red China, Jabara and the 337th went to Taiwan, where they flew their F-104s near the coast of mainland China for three months. ‘We used to fly up and down the Straits of Formosa at…twice the speed of sound,’ Jabara recalled, ‘and had the Chinese Communists take a look at us on their radar…I’m sure it shook them up a little.’

Jabara flew with the 337th until July 1960, when he returned to the United States and entered the Air War College at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala. After graduation in June 1961, he took command of the 43rd Bomb Wing at Carswell Air Force Base, Texas, where he flew supersonic Convair B-58 Hustler bombers. In July 1964, he took command of the 4540th Combat Crew Training Group at Luke Air Force Base, Ariz., where pilots from NATO countries were trained to fly the F-104G Starfighter.

Colonel Jabara took command of the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing at Homestead Air Force Base, Fla., in 1965. In 1966, with his tour at Homestead coming to an end, Jabara volunteered for combat duty in Vietnam. On November 17, 1966, he and his family were driving on Florida’s Sunshine State Parkway on their way to Myrtle Beach, S.C., where his family would wait out his planned Vietnam tour.

Jabara was in the back seat of a Volkswagen driven by his daughter, Carol Anne. Near Del Ray Beach, Fla., they came to a road construction site. Carol Anne lost control of the car, and the Volkswagen rolled over several times before stopping. Jabara and his daughter were rushed to a Del Rey hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival from head injuries. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on November 24, 1966.

‘Heroes die young,’ Professor Craig Miner wrote. ‘Jabara died in his fighting prime, ready and able as ever to enter the cockpit and follow the target….We do not remember him as an old man telling of distant exploits, but as a young man in the midst of them.’

This article originally published in the March 1995 issue of Aviation History magazine. For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!