“Tell Jabara the Mexican got two.” The transmission from U.S. Air Force Captain Manuel J. “Pete” Fernandez Jr., inbound from MiG Alley on March 21, 1953, likely stung the pride of his 334th Squadron mate Major James “Jabby” Jabara. Once Fernandez’s ninth and 10th MiG-15 victories were confirmed, Pete (whose ancestry actually traced from Spain to Cuba) joined an exclusive club of double jet aces. Meanwhile, since returning to Korea that January, Jabby seemed to have flamed out in the Sabrejet ace race.

Jabara (himself of Lebanese heritage) had won the April-May 1951 sprint to crown America’s initial North American F-86 Sabre ace. “Stick him out in front and see what he can do,” ordered then Fifth Air Force commander Lt. Gen. Earle E. Partridge.

After downing his fifth and sixth MiGs on May 20, Jabara was whisked Stateside for the sort of homecoming later bestowed on astronauts. “If you shoot down five planes,” novelist James Salter, himself a Sabre pilot, wrote, “you join a core of heroes. Nothing less can do it.”

Jabara’s feat, achieved during his 63rd mission, came when USAF dominance in MiG Alley—an area in northwestern North Korea along the Yalu River bordering Manchuria—was doubtful. As Blaine Harden, author of several incisive Korean War books, explained in an interview: “When the Korean air war began, the MiGs made it a kind of slaughter. And their pilots were Stalin’s elite.”

New to the “core” of aces that September were Captains Richard S. Becker and Ralph D. “Hoot” Gibson. Arguably, these earliest jet aces stood out for dueling Stalin’s “honchos” while piloting F-86s that were inferior to their adversaries’ MiGs. In Becker’s estimation, “We fought them to a draw.” Jabara, unwilling to rest on such laurels, itched to get back in action.

Edging out the Communists proved just a matter of time. “Stalin’s elite were replaced by much less skilled Russians,” explained Harden, “and then by much, much less skilled Chinese and North Koreans.” Kenneth Rowe, a former North Korean pilot who defected to the West, noted, “We were trained by less experienced MiG pilots.” Rowe (formerly No Kum-Sok) elaborated: “The Russians wanted to train North Koreans in a hurry so we can speak Korean in the air. Crash training and then go out and fight so they can prove North Koreans fly.”

Meanwhile, said Harden, the F-86 improved: “Increased speed, maneuverability, targeting. The MiG improved somewhat but it was a much more difficult aircraft to fly and its manufacturing tolerances were much less precise. As time went by, those things tolled.”

Roughly a month after Becker and Gibson were sent back to the States, in October 1951 World War II ace Major George A. Davis brought to Korea utter contempt for his MiG opponents. Davis, fifth to join the core of aces (Major Richard D. Creighton qualified three days before him), contracted what many termed “MiG fever”—a dangerous addiction to pursuing MiG kills.

Davis’ two kills on December 13 made him America’s first jet double ace. Had he not been a squadron commander, Davis might have been recalled. Instead, constrained by higher-ups to one sortie a day, he pushed his luck. Finally, on February 10, 1952, during his 60th mission, he began a reckless prowl that earned him two more MiG kills, but also cost his life.

Davis’ stunning loss handed the Communists a propaganda coup and dealt a devastating blow to 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing morale. New air group commander Colonel Walker “Bud” Mahurin shared his pilots’ exasperation with the enemy’s ability to flee to sanctuary in Manchuria. Mahurin’s men “literally saw the airfields on the other side of the Yalu River and the planes coming up,” author Kenneth P. Werrell, who interviewed many MiG Alley veterans, told me.

Skirting official policy, Mahurin secretly authorized flights across the Yalu. “It might be dirty pool,” Mahurin later conceded, but “every MiG counted.” While cross-Yalu forays were not un-precedented, the spring of 1952 marked a watershed, according to Ken Rowe. “April of 1952, that’s when American jets started coming to Manchuria openly,” he recalled. “MiGs landing, MiGs taking off—they were shot. MiGs go to North Korean skies; when they come back American jets are waiting in Manchuria.”

Meanwhile, stalemate on the ground and America’s improved fortunes aloft drew press attention to MiG Alley. Observed aviation author Thomas McKelvey Cleaver: “Air combat was played up the same way as in World War I. You had a battlefield where nobody was winning. News reporters sensed a horse race [in MiG Alley] and they couldn’t take their eyes off it.”

That fall, Pete Fernandez, then 28, reached Korea. Though qualifying for fighters during World War II, Fernandez never saw combat. Eventually becoming an aerial gunnery instructor at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, he watched in frustration as his students deployed. “He had trained all these youngsters,” his father, an Air Force colonel, later told reporters. “They were all gone, and he wasn’t going.”

Fernandez achieved early success as an element leader with the 334th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (FIS). As he claimed single victories each month from October to January, however, one of his Nellis acolytes struggled to gain his footing.

Approaching age 31, New Hampshire–born 1st Lt. Joseph C. “Mac” McConnell Jr. had risen from the ranks to navigate B-24s during World War II but had not pinned on USAF pilot wings until 1948. Flying F-86s in Alaska when the conflict in Korea broke out, Mac, then 28, was judged too old to go. Still, he exuded confidence, telling another Korean-bound pilot, “I know I’m going to make ace.”

While Fernandez flew lead and racked up kills with the 4th Wing, McConnell flew with the 51st Wing. Not until January 1953 did his gunnery prowess, perfected under Fernandez’s tutelage at Nellis, earn him lead in the 39th FIS. Following his initial victory on January 14, McConnell downed three more before month’s end. Both now stood one victory shy of the core.

Meanwhile, back in the States, Jabara’s restlessness drew notice. According to a November 12 dispatch: “Major James Jabara, the Air Force’s first jet ace, today asked to be returned to combat duty in Korea. The 29-year-old…said in his application, ‘I want to…finish the tour interrupted in May 1951.’”

It was a delicate matter. After George Davis’ February loss, his grieving widow, pregnant with their third child, accused the Air Force of keeping her husband in Korea rather than returning him (like Jabara, Becker and Gibson) a living hero. The Air Force countered that its current policy was “keeping all jet pilots—including aces—in Korea until they had finished their normal tour of 100 combat missions.”

Recommended for you

The USAF now walked a tightwire to preserve its ace heroes. On October 3, 1952, Major Frederick C. “Boots” Blesse, who’d voluntarily extended his tour, destroyed his 10th MiG during mission 123. Afterward, low on fuel, Boots parachuted offshore, forcing a rescue helicopter to dodge enemy fire to pluck him from the drink. Fifth Air Force promptly shipped the double ace home. Thus, it was no small concession to allow Jabara’s return.

“I feel it’s my duty…it’s what I should do,” Jabara insisted to reporters on January 8, 1953, as he climbed aboard a Tokyo-bound Navy R6D cargo plane.

Reporters assumed it wouldn’t take long for Jabara to score again. A February 17 New York Times article mentioned how, amid nonstop MiG Alley confrontations, “Maj. James Jabara, on his second tour of duty in Korea, damaged a MIG.” Nonetheless, Jabara’s victory count stubbornly stalled at six. For their parts, McConnell, with a victory on February 16, and Fernandez, with two victories on February 18, became America’s 26th and 27th jet aces.

The 4th Wing commander, Royal “King” Baker, then atop the leader board with 11 victories (his first a propeller-driven Lavochkin La-9), welcomed the Reds’ reckless aggression: “The more planes they put in the air…the more targets we have.”

King kept scoring into March. “I’ve always thought Friday the 13th was good luck for me,” he quipped to reporters after scoring number 13 on Friday, March 13. But the next day, after 127 missions, with his scheduled rotation still 12 days away, Baker abruptly—and voluntarily, Air Force sources insisted—stood down. “The crack flyer,” read a news service dispatch, “was quoted as having said: ‘I feel I have done my job over here.’” Indeed, though Baker’s overall total fell one shy of Davis’, his 12 MiG-15 victories outpaced Davis’ 11 (the fallen ace had also been credited with three Tupolev Tu-2 bombers).

With Baker’s departure, the ace race focus shifted to Captain Harold E. “Hal” Fischer Jr., a 51st Wing pilot then outpacing Fernandez’s victory count nine to six. Fischer, a “shy, blue-eyed 27-year-old fellow off an Iowa farm,” was, at least according to 39th FIS personnel, certain to top both Baker and Davis. “With more than 30 missions to go,” remarked a squadron officer, “how can Hal miss?”

Fischer’s ascendency proved brief. He made double ace with a victory on March 21 only to have Fernandez’s two kills match his total—and double-ace stature. Then, on April 7, during his 70th mission, Fischer punched out of his crippled Sabre. Captured across the Yalu, he languished in a Chinese prison as the ace race baton passed to Pete Fernandez.

One newspaper account portrayed Fernandez as having “little time for anything other than flying.” (“I hadn’t heard of Marilyn Monroe,” he claimed.) According to aviation author and MiG Alley veteran John Lowery, who occasionally flew with Fernandez, such single-mindedness enabled Pete to devise a technique that later became 4th Wing doctrine. Climbing to 49,000 feet, Fernandez flew deep into Chinese airspace before turning south. Cruising at .90 Mach he literally joined up with MiG formations. Any opponent taking the bait invited a deadly spinning stall.

MiG-15 pilot Rowe recalled once battling such subsonic gremlins: “At .92 Mach, my control stick didn’t respond. Plane started shaking, like I’m being hit by rocks. You cannot do anything.” Rowe somehow managed to regain control and return to base, but a MiG pilot Fernandez encountered on April 17 didn’t. “The Red jet flew out of control in a spin and the pilot bailed out,” reported Florida’s Tampa Times. Perhaps, the paper mused, “the Red pilot…recognized his adversary…and decided to throw in the towel.” Without firing a shot, Fernandez had earned his 11th MiG victory.

McConnell, meanwhile, showed no intention of throwing in the towel. During an April 12 morning duel, Major Semyon A. Fedorets, one of the few Soviet pilots to succeed late in the war, bested him. Fedorets registered McConnell as his sixth victory but not before Mac reciprocated, making Fedorets his eighth. The Soviet major was hospitalized for a month while McConnell, promptly rescued at sea, assured squadron mates, “I barely got my feet wet.”

That May, bent on bringing the Communists to terms in armistice talks at Panmunjom, America’s Far East Air Forces launched more than 22,000 sorties. Though F-86 pilots had long been trespassing into China—subject to occasional discipline or grounding—now, according to Lowery, the gloves came off. “I was present when the 4th Wing intelligence officer said: ‘[Fifth Air Force commander Lieutenant] General [Glenn] Barcus says screw the Yalu River…go where they live.’”

The Communists saw it differently. It was Joseph Stalin’s March 5, 1953, death, argues military historian Xiaoming Zhang, “rather than U.S. air pressure, that finally brought a breakthrough in armistice negotiations.” Hoping to get as many ground troops combat experience as possible, the Chinese staged a big summer ground offensive supported by 350 Chinese MiGs plus three North Korean MiG units. This bid for air superiority, however, employed many inexperienced pilots.

As a result, the skies over northwest Korea increasingly resembled an American game preserve. New York Times reporter Robert Alden wrote, “The [USAF] pilots…are spoiling for a fight [while] the Communists seem unenthusiastic and poorly trained.”

The Sabre ace race was now a two-man contest with Fernandez, pride of 4th Wing, holding the lead but McConnell, pride of 51st, never far behind. Mission count became crucial: Pete neared 125; Mac crossed the century mark. But so did USAF concern about losing aces so close to a possible armistice.

Finally, on May 17, with Fernandez’s victory count at 14.5 and McConnell’s at 13, General Barcus intervened. “He issued an order that Pete and McConnell had enough kills,” said Lowery. “They should immediately stop flying combat and go home. I remember when the order came into the 334th, but McConnell’s people claimed they didn’t get it, and so he flew the next day.”

Fernandez joined Barcus at Fifth Air Force headquarters on May 18. “The air was full of MiGs and Captain Fernandez bit his lips and waited,” reported the Times’ Alden. Soon, pilot transmissions came in. “My God, there must be 30 of them!” exclaimed Dean Abbott, McConnell’s wingman. “Yeah, and we’ve got them all to ourselves,” Mac replied.

Afterward, when a phone rang, Barcus took the receiver and listened. “I can’t tell him that,” the general snapped. “If I do, I won’t be able to keep him on the ground.”

Barcus sheepishly pulled Fernandez aside. “Pete, McConnell got two this morning.”

Fernandez managed a thin smile. “Good show,” he said.

That afternoon, once McConnell tallied his third victory for the day, Barcus famously demanded: “I want that man on his way back home to the U.S.A. before you hear the period at the end of this sentence.”

In the wake of Fernandez and McConnell’s simultaneous departure, dank monsoon weather settled in, making it unlikely that others could overtake them. Yet that June, with the Communist offensive now in full swing, Sabre-MiG activity reached unprecedented levels: 1,268 MiG sightings, 507 engagements, 77 destroyed. And eager to claim his share—and likely deliver a riposte to Fernandez’s March 21 jibe—was Jabby Jabara.

It had taken Jabara until May 16 to claim his seventh victory. “I’ve made mistakes,” he conceded to reporters. “I still have a long way to catch up.” But catch up Jabara did, with a double one day in late May and five more victories (including two doubles) in June to reach 14.

Jabara played every angle, recalled Lowery, who flew at least six missions with him. “When he got on the schedule, he would tell the maintenance officer to put extra ‘rats’ [small blocks installed on the inside edge of the tailpipe lip] in the tail. It would give him more thrust.”

Not only that: “When you sat down to brief, he gave you a pill. I said, ‘Major Jabara, what’s this for?’ He said: ‘This is a MiG pill, it’ll make you see better.’ I have since learned it was an ‘upper’—I never did take it.”

Apparently, the “MiG pill” didn’t help the ace some called “Cousin Weak Eyes.” On June 15 Jabara mistakenly opened fire on 1st Lt. Richard Frailey, one of his favorite eagle-eyed wingmen. “Jabara, you’re shooting at me!” screamed Frailey as “friendly fire” peppered his plane. Luckily, Frailey bailed out and was rescued.

Jabara’s apology to Frailey was a rare concession to a wingman. While it was customary, for example, for the first pilot in a flight who spotted a “spinner” (a MiG in a high-altitude spinning stall) to claim a victory, when Jabara led a flight all spinners were his.

Exhausting every angle, Jabara finally claimed victory 15 on July 15—the 99th mission of his second tour. He’d bested Fernandez, becoming America’s second triple jet ace, but still yearned to overtake McConnell. It was not to be. “The Wichita flier wound up his tour yesterday,” reported the Associated Press on July 18, “by prowling the skies in a vain search for his sixteenth victim.”

Afterward, grounded, Jabara contemplated the future. “I’m going to be sitting out one of those jet desk-jobs,” he groused.

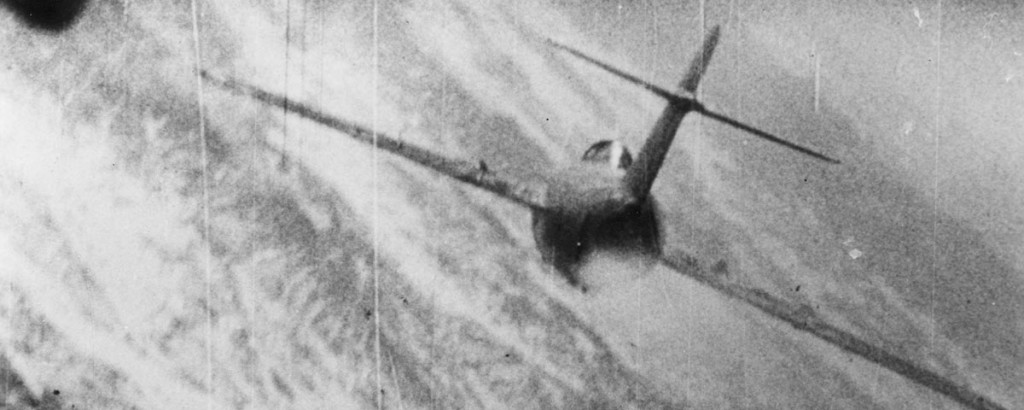

On September 21, 1953, North Korean air force fighter pilot Sr. Lt. No Kum-Sok managed to escape North Korea in a new MiG-15bis. Landing at Kimpo Air Base near Seoul, South Korea, his MiG allowed the U.S. Air Force to unlock the airplane’s secrets.

Disassembled and flown in a Douglas C-124 transport to Kadena Air Base, on Okinawa, the MiG (below) was first tested by Lt. Col. Eugene M. Sommerich, operations officer from the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing, who had combat experience against the aircraft type. He had flown to Okinawa in an F-86F-30 Sabre, which was used to chase the MiG during tests. Test pilots from the Wright Air Development Center who also flew the airplane included the center commander, Maj. Gen. Albert Boyd, Major Charles E. Yeager and Captain T.E. “Tom” Collins.

The MiG’s weapons consisted of a 37mm cannon and two 23mm guns. The gunsight was a simple gyro type, similar to the Mk-18 gunsight used on the first few F-86As.

Tests of the MiG showed its service ceiling was 51,500 feet, but the test pilots were able to coax it to 55,100 feet. Still, at those ultra-high altitudes the aircraft was flying very close to its low-speed buffet boundary, or stall point, and the slightest maneuvers could precipitate a loss of control. The airplane also was found to have no perceptible pre-stall warning and was prone to accidentally enter a spin, from which recovery was difficult.

At high airspeeds the building shock wave caused the flight controls to become unresponsive. The increasingly turbulent boundary-layer airflow triggered flight control buffeting at .91 Mach, becoming heavier as the Mach number increased. At .93 Mach the aircraft exhibited a strong nose-up tendency. The biggest surprise was that the MiG-15bis had a terminal velocity of .98 Mach but was officially limited to .92 Mach.

In a determined effort to establish the MiG’s maximum airspeed, Major Yeager took the airplane to 55,000 feet and rolled into a vertical dive, with Captain Collins waiting at 48,000 to chase him. As Yeager passed by, Collins could see the MiG’s elevators moving but with no response from the airplane. At 12,000 feet the nose of the aircraft abruptly pitched up, and the controls began to react normally. But it wasn’t until reaching 3,000 feet that Yeager finally regained complete control.

“Flying the MiG is the most demanding situation I have ever faced,” Yeager wrote in his autobiography. “It’s a quirky airplane that’s killed a lot of its pilots.”

Today Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University professor emeritus Kenneth Rowe, the former No Kum-Sok, lives in retirement with his wife in Daytona Beach, Fla. His MiG-15bis is displayed at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

—John Lowery

Military historian David Sears is currently completing Duel in the Deep, a forthcoming book about U.S. Navy air/sea hunter-killer groups during WWII’s Battle of the Atlantic. Further reading: Life in the Wild Blue Yonder, by John Lowery; Sabres Over MiG Alley, by Kenneth P. Werrell; and The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot, by Blaine Harden.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!