With 14 victories to his credit, Major George A. Davis Jr. was the highest-scoring American ace of the Korean War when he was shot down and killed over North Korea on February 10, 1952.

His loss was a major blow to the United States, and represented a big propaganda coup for the Communists. The air battle in which he was downed generated plenty of controversy, probably more so than any other single action of the Korean War. After Davis’ death, his wife Doris, pregnant with their third child, was openly critical of the U.S. Air Force and the war in general. With newly available information from China, we now know that this action also caused a great deal of controversy and embarrassment for the Chinese.

Prior to Korea, George Andrew Davis Jr. of Dublin, Texas, was already an ace with six victories over Japanese aircraft during World War II. Flying P-47 Thunderbolts with the 342nd Fighter Squadron, 348th Fighter Group, Davis had mastered the difficult art of deflection shooting. In Korea, he continued to impress with his excellent marksmanship while piloting a North American F-86A Sabre with the 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing. The older-model F-86A lacked a radar-ranging, lead-computing gunsight, yet Davis was able to quickly score an impressive number of victories in it. His excellent marksmanship earned him the nickname “One-Burst Davis.”

There is good evidence from Communist records that most of Davis’ victory claims are valid. He made his first two claims on November 27, 1951—the same day two other USAF pilots also got confirmed victories—while the Soviets recorded two losses from the 324th Fighter Aviation Division (FAD). On November 30, Davis claimed three Tupolev Tu-2 bombers and a MiG-15. Chinese records for that action showed the loss of four Tu-2s from the 8th Bomber Aviation Division and a MiG-15 from the 3rd FAD. Davis claimed two of the four confirmed victories (plus two “probables”) awarded to USAF pilots on December 5. Communist records actually showed a total of six losses, four from the Chinese 4th FAD and one each from the Soviet 303th and 324th divisions. On December 13, Davis claimed two victories in the morning and two in the afternoon, out of a total of 14 confirmed victories awarded. Communist records reflected 11 losses, nine from the newly arrived Chinese 14th FAD and one each from the Chinese 3rd FAD and Soviet 303rd FAD.

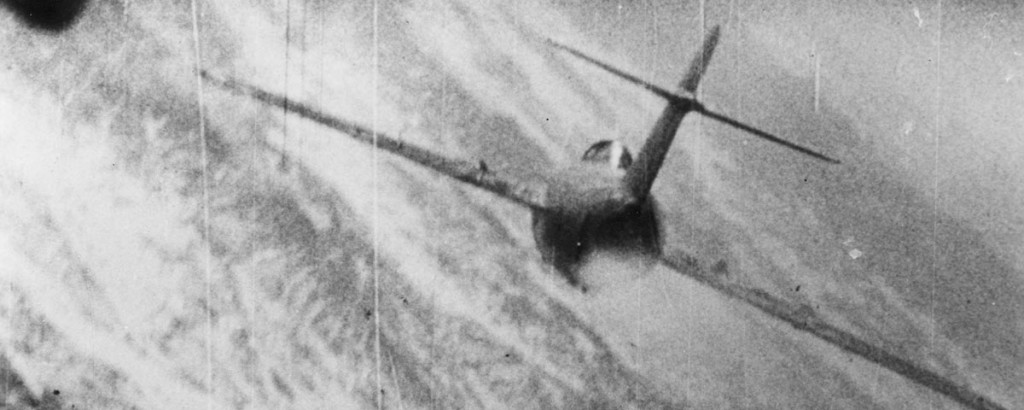

On February 10, 1952, Davis was part of a formation of 18 Sabres patrolling MiG Alley. A member of Davis’ Baker Flight developed oxygen problems, and was escorted back to base by another Sabre. When Davis spotted contrails west of the Yalu River, he broke away from the rest of the formation and led his wingman, Lieutenant William W. Littlefield, to investigate. Upon reaching the Yalu but finding no targets, Davis turned back. But then, cruising at 38,000 feet, he spotted 10 MiG-15s below, heading southeast. He led his wingman down to attack them from above and behind. Selecting a MiG at the rear of the formation, Davis fired a burst, hitting it near the right wing root. The enemy jet spewed smoke and went down.

However, instead of using the speed gained from his dive to zoom-climb out of danger, Davis extended his speed brakes to slow down and tried immediately to get behind another MiG. Littlefield noted that in the process of maneuvering they passed several MiGs in the flight. Davis fired a single burst at another MiG, again hitting hit his target in the right wing root. The second MiG also spewed smoke, rolled to the left and went down.

Littlefield radioed Davis to warn him that a MiG was closing and firing from his 7 o’clock position. Davis, possibly concentrating on attacking a third MiG, did not respond. Littlefield observed a heavy hit below the canopy on the left side of Davis’ F-86, whereupon it rolled to the right and headed straight down. He followed Davis’ descent, frantically calling for him to eject, but he never responded. At one point the major’s Sabre briefly pulled up from its dive and headed southeast with its landing gear extended and streaming smoke. It then started to porpoise, before rolling left and crashing into a hillside.

During his descent, Littlefield was also attacked by a number of MiGs. He made one snap shot at a passing MiG but did not observe any hits. He returned to base to face grilling by other members of the 4th Wing for allowing his famous flight leader to be shot down.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Chinese troops from the 149th Division reached the crash site and found Davis dead in the burnt-out wreckage. They recovered his dog tags and quickly discovered his identity. The Americans had publicized Davis’ aerial victories, and the Communist senior commanders wanted to exploit this great propaganda coup. They launched an immediate investigation to identify the victorious pilot, and quickly learned that the 12th Fighter Aviation Regiment (FAR) of the Chinese 4th FAD had been involved in the air battle. One of its flight leaders, Zhang Jihui, adamantly claimed to have scored the victory. Although other pilots in the action disputed his account, Zhang received official credit. This was communicated to Chairman Mao Zedong in a February 23 telegram.

Zhang was made a “Combat Hero First Class,” and the Chinese propaganda machine had a field day. They hailed Zhang as a proletariat pilot with only a few hours of jet experience who had nevertheless bested America’s top ace in single combat. The Soviets also claimed one of their pilots, Mikhail A. Averin, had shot down Davis, but that can be easily discounted since their action occurred in a different location to the north.

In most of the Communists’ published accounts, Chinese losses were not even mentioned, but in recent years some details began to surface. Communist Party documents not intended for public consumption began to leak out, including the February 23 telegram to Chairman Mao. It revealed that three MiG-15s had been shot down during the battle, including Zhang’s. No other U.S. pilot claimed victories on February 10, 1952, and the only two confirmed victories for the day were awarded to Davis on the basis of Littlefield’s report. So, who could have shot down Zhang after he allegedly downed Davis?

According to Zhang’s own description, both he and his wingman were shot down while making a tight right turn after downing two F-86s. His version of events was clearly not consistent with Littlefield’s. Furthermore, Zhang landed within 500 meters of Davis’ crash site after ejecting. This is also inconsistent with Littlefield’s account since Zhang claimed to have shot down two Sabres flying in one direction, and then was himself shot down after making a hard right turn, i.e., headed in the opposite direction. In light of these maneuvers, the obvious question was how Zhang could have ended up landing so close to Davis’ crash site.

The answer seems to lie in recently revealed evidence. Hou Shujun, another flight leader in the 12th FAR, was so incensed by Zhang’s claims that he published his own account of the action. What we take for granted in the West—publishing a sensational exposé—was illegal in Communist China, and Hou risked imprisonment for breaking with the party line. One of his shocking revelations was that five, not three, MiG-15s were lost during the February 10 action, a fact supported by unit records and two pilots who survived by ejecting. Hou even interviewed members of the 149th Division who were on the ground at the time and reported seeing six planes crash in rapid succession, with the American fighter coming down last. He cites this as evidence that Zhang went down before Davis.

Recommended for you

According to Hou, Zhang and his wingman, Shan Ziyu, were originally part of a 12-plane formation from the 12th FAR, 4th FAD. The formation consisted of two V-shaped flights of six planes. Deputy Regiment Commander Li Wenmo led the first flight, with Zhang and Shan in the no. 5 and no. 6 positions on the right side of the V. During the flight to their patrol area, Zhang and his wingman dropped out of formation and lagged so far behind that Hou could not see them. This is consistent with Littlefield’s report of seeing a formation of 10 MiGs.

Zhang claimed that he had left formation to investigate sightings over the sea. He was on his way back to rejoin the flight when he spotted “eight Sabres” attacking friendly fighters. He said he shot down two Sabres, after which he and Shan were shot down. Zhang’s wingman was killed and could not corroborate his account.

Zhang’s supporters pushed the hypothesis that he and Shan returned to the 10-plane formation just as Davis and Littlefield attacked. Davis shot down three MiGs before Zhang supposedly shot him down. But then, how to explain both Zhang and his wingman also going down? Friendly fire, accidentally entering a spin or Littlefield’s “snap shot”? Here’s a scenario that seems to fit the evidence:

Davis spotted the 10-MiG formation and attacked the rearmost six-plane flight. From Chinese records we know the no. 4 MiG on the left of the V was lost, along with its pilot, Wang Deyu. He was almost certainly Davis’ first victim. Davis then banked into a right turn, overshooting several MiGs in the process. The closest MiGs he could pass were the no. 3 on the left of the V, and the nos. 5 and 6 on the right. Hou’s account revealed that the no. 5 and no. 6 MiGs on the right of the rear V were shot down. Both pilots, Wang Zeping and Zhai Ziqing, ejected and survived. By Littlefield’s account, he and Davis would have likely overshot these two in their right turn following the first firing pass, making it impossible for him to have attacked them. That leaves Zhang, who claimed he attacked two of eight Sabres stalking “friendly planes.”

From Zhang’s vantage point as he approached from behind, the two F-86s and six MiGs of the rear V might have looked like eight Sabres stalking the four MiGs in the front flight. If so, then the two Sabres that Zhang claimed could have actually been Wang’s and Zhai’s MiG-15s.

While this was happening, Davis could have gotten on the tail of Zhang’s wingman, Shan, shot him down and then hit Zhang. Then another MiG in the rear flight hit Davis with a lucky shot, sending him down near where Zhang landed after ejecting.

Hou and the no. 3 MiG’s pilot, Lu Songting, both claimed to have made snap shots at an F-86. It is unclear whether their targets were Davis or Littlefield. Gun camera film was inconclusive, but Soviet advisers thought that Lu had a better chance of having scored a hit. The four MiGs of the front flight eventually flew back to base, never realizing that the rear flight had been attacked.

So, in conclusion, even though the Chinese have long claimed that Zhang Jihui shot down Major George Davis, the evidence does not support that contention. It is likely that Zhang was responsible for the downing two MiGs in a friendly fire incident, and that a lucky shot, possibly from Lu Songting, caused Davis’ death.

Such was the nature of Korean War air combat, which pitted two similar-looking jet fighters against one other in fast-paced, long-range dogfights. The number of documented friendly fire incidents on the U.S. side—sometimes resulting when American pilots ventured across the Yalu River hunting for MiGs—strongly suggests that similar scenarios played out for the Communists as well.

Raymond Cheung served as a correspondent for a number of UK defense journals, writing mainly on naval matters, though his first love is aviation history. His most recent book is Aces of the Republic of China Air Force. Suggested reading: Crimson Sky: The Air Battle for Korea, by John Bruning; and Red Wings Over the Yalu: China, the Soviet Union and the Air War in Korea, by Xiaoming Zhang.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!