Most American history textbooks explain that the War of 1812 grew out of American grievances over U.S. vessels being stopped by British warships and their seamen being pressed into Royal Navy service as “deserters,” with the added provocation of the British helping Native American tribes that resisted the settlement of the western frontier. A less mentioned casus belli, however, was the push to conquer Canada advanced by the young “War Hawks” faction in the U.S. Congress.

Just weeks after it declared war on Great Britain on June 18, 1812, the United States launched its first invasion of Upper Canada (now Ontario Province) from Michigan Territory on July 12. Under the unsteady hand of Brigadier General William Hull, the operation did not go well, ending with Hull’s withdrawal to Detroit and followed, on August 16, by the only surrender of a U.S. city to a foreign invader. A succession of subsequent attempts also came to nothing, including the taking, partial burning, and ultimate abandonment of York (now Toronto) in April 1813.

The Saint Lawrence campaign, as the eighth of these U.S. invasions came to be known, was another grand effort, involving two armies acting in concert to seize control of the Saint Lawrence River and Lower Canada (now Quebec Province). A classic study of the failure to coordinate an offensive at both the strategic and tactical levels, it would also feature one of the war’s bloodiest land battles and an encounter that became iconic to a nation that had yet to exist.

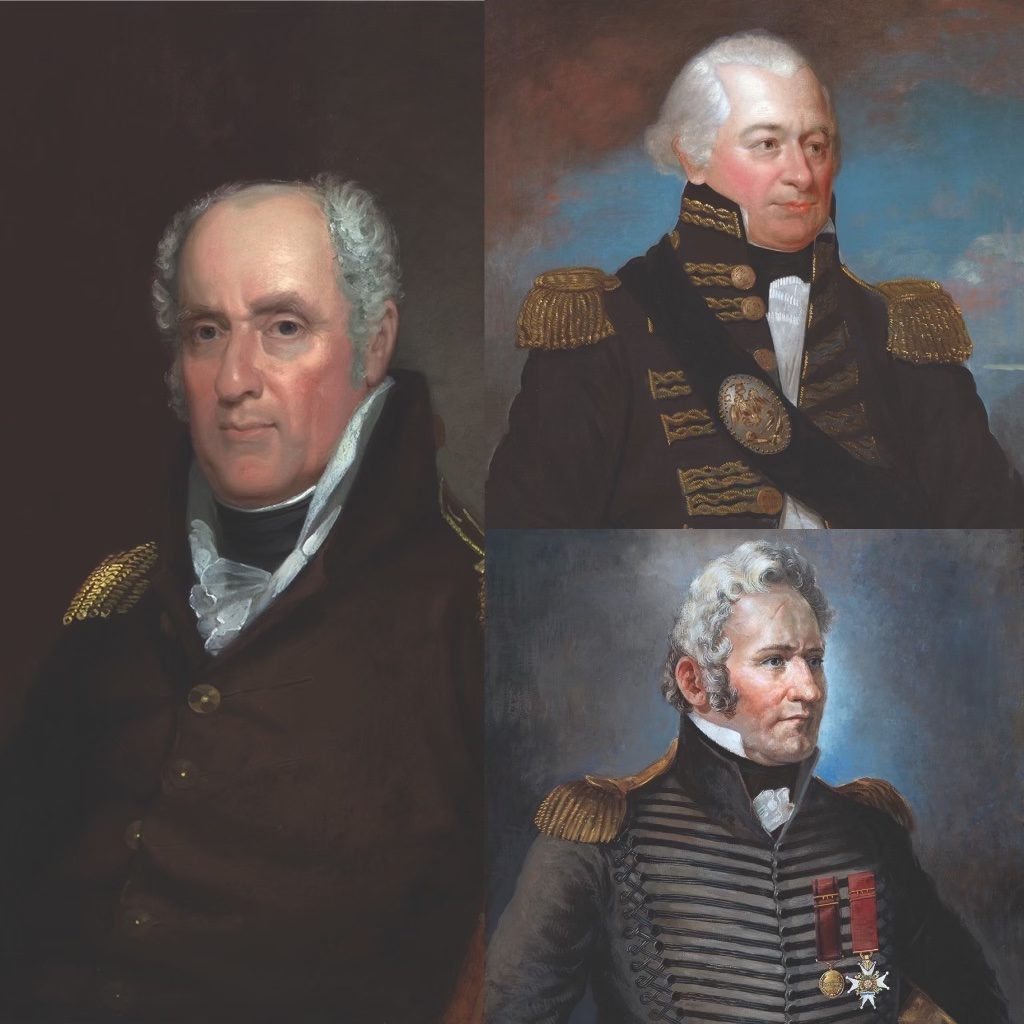

John Armstrong Jr., the U.S. secretary of war, conceived the Saint Lawrence campaign with the intention of commanding it personally. His plan, launching from New York, was to have Major General James Wilkinson lead 8,000 troops, accompanied by a squadron of supporting gunboats and bateaux, out of Sackett’s Harbor along the Saint Lawrence River, while Major General Wade Hampton led another 4,000 men north from Plattsburgh. The two forces would meet and take the city of Kingston, at the mouth of the Cataraqui and Saint Lawrence Rivers on Lake Ontario—an objective subsequently changed to Montreal as a prelude to conquering all of Lower Canada.

But the plan went awry virtually from the beginning, as Armstrong fell ill and left it to his two division commanders to carry out the invasion. Moreover, though both men were veterans of the War for Independence, Hampton was loath to work alongside Wilkinson, with whom he had not been on speaking terms since 1808.

Hampton was not alone in despising his erstwhile partner. Wilkinson, who had been serving since 1800 as general in command of the U.S. Army, carried a careerlong reputation for shady dealings that frequently attracted indictment but somehow always eluded conviction. (Only in 1854 would it be confirmed that Wilkinson, using the codename Agent 13, had been keeping Spain informed of all American activities in the western frontier—even when he was commander in chief of the U.S. Army.)

The War of 1812 gave Wilkinson a last chance at redemption, but by the summer of 1813 his principal achievement had been the occupation of Mobile in Spanish West Florida. When he replaced Major General Henry Dearborn in command at Sackett’s Harbor that July, he had more substantial prospects, but soon after Armstrong’s arrival with his invasion plans, Wilkinson also fell ill.

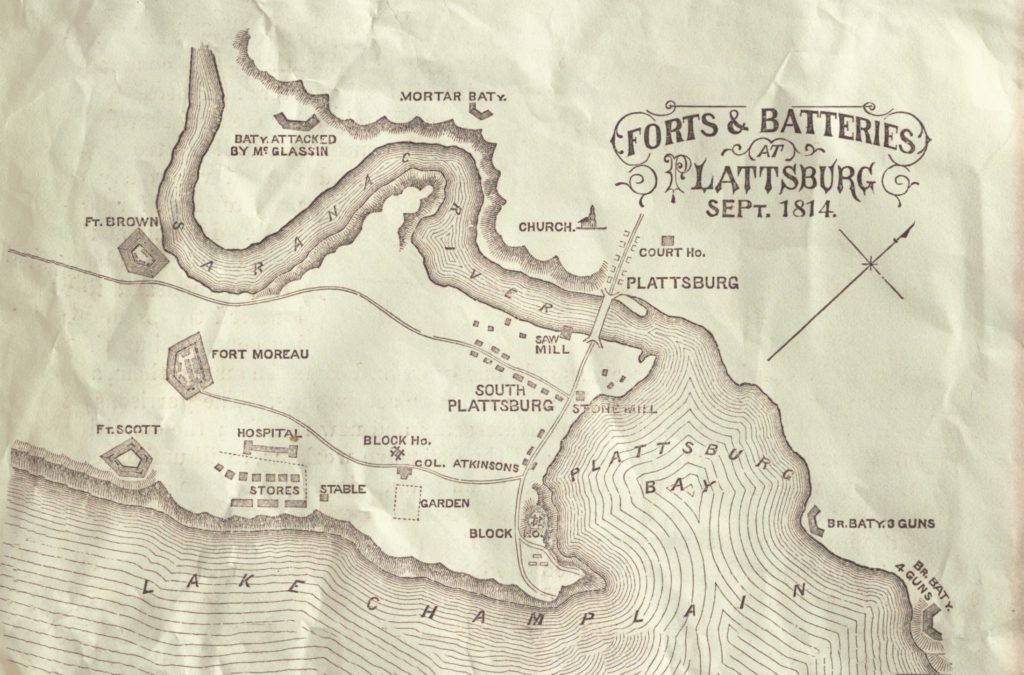

As Armstrong and Wilkinson convalesced, Hampton, a 61-year-old South Carolinian who was one of the wealthiest landowners in the United States, discovered that most of his troops were poorly trained and his supplies barely sufficient to sustain a march, let alone a siege along the way—on top of which was the fact that British gunboats dominated Lake Champlain. He was also so averse to taking orders from Wilkinson that Armstrong had to assure Hampton that they would be forwarded through the War Department instead.

Hampton set out from Burlington, Vermont, on September 19, but on reaching Plattsburgh he turned west to bypass Lake Champlain and the 900-man British army and naval base on Île de Noix. Hampton established his next base at Four Corners on the Châteauguay River. He resumed his march on October 18, when he received a communiqué from the still-ailing Armstrong, who had left Sackett’s Harbor two days earlier, stating that Wilkinson’s division was about to get underway. But Hampton’s 1,400-man brigade of New York militia adamantly refused to cross the border and fight people with whom they had been on friendly terms for decades. Consequently, when Hampton entered Lower Canada, his force totaled 2,600 U.S. Army infantrymen, 200 cavalry, and had 10 field guns.

After more than a year of hostilities, Britain still viewed the “American War” as an unwelcome distraction from its main priority: fighting Napoleon’s armies in Spain. It had increased its regular army forces in America to more than 13,000 men, but to supplement their meager numbers these scattered units depended on five fencible regiments—defense units made up of local conscripts with British commanders—as well as a variety of local militia units and allied Indian tribes. On learning that his city was the target of the next U.S. invasion on September 17, Major General Louis de Watteville, the Swiss-born commander of the Montreal District, ordered the militia raised, while the governor general of North America, Lieutenant General George Prevost, ordered the 1st Light Battalion, a composite of British regulars and Canadian militiamen led by Lieutenant Colonel George MacDonnell, to march from Kingston to a blocking position south of Montreal.

In the meantime, the principal force standing in Hampton’s way was a mixed bag of militia north of the Châteauguay River, near the junction with the English River. Its nucleus, the Voltigeurs de Québec, was a light infantry regiment of French Canadians who, while loyal enough to the British Crown, refused to wear red coats, preferring militia gray uniforms with black bearskin hats. Its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry, trained his men with hardnosed professionalism acquired during previous service in the Napoleonic Wars. About a hundred of the Voltigeurs had gained some experience at the First Battle of Lacolle Mills on November 19, 1812, when Salaberry led them and 230 Kahnawake Indians to repulse some 650 U.S. Army invaders.

Once MacDonnell arrived to supplement his Voltigeurs and local militia, Salaberry established an abatis of tree branches to block the road at a ravine near the English River junction. There he waited with 150 of the Voltigeurs, 50 Canadian Fencibles, 100 sedentary militia, and two dozen Indians. Behind that first line of defense he left MacDonnell in charge of a series of reserve lines, totaling 300 Voltigeurs, 480 troops of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Select Embodied Militia, 200 sedentary militia, and 150 Indians, to guard the river, including Grant’s Ford.

While local farmers kept Salaberry and his officers well informed about enemy movements, the Americans proceeded blindly. Hampton did know about Grant’s Ford, however, and on the evening of October 25 he dispatched Colonel Robert Purdy with his 1st Brigade and the light companies of the 5th, 12th, and 13th U.S. Infantry Regiments on a 16-mile march to cross the Châteauguay and flank the enemy from the south the following dawn. Poorly guided, Purdy’s 1,000 troops got lost in the woods and spent a miserable night under a pouring rain.

The next morning, October 26, Hampton received a dispatch from Armstrong stating that he was departing Sackett’s Harbor and leaving overall command to Wilkinson. He ordered Hampton to prepare winter quarters for 10,000 troops along the Saint Lawrence. Sensing that the whole campaign was being written off, Hampton wrote a letter resigning his generalship, and he would have withdrawn forthwith but for Purdy’s lost brigade. Instead, he committed his 2nd Brigade, under Brigadier General George Izard, to a frontal assault.

Meanwhile, at dawn, Purdy had found the correct path north, but his brigade was again misguided, so that at midmorning most of it emerged from the woods just south of Salaberry’s first line of defense. The 3rd Select Embodied Militia attacked the Americans but was driven back, with its two highest ranking officers wounded. Hotly engaged by more militia and Indians, some of Purdy’s troops retreated only to come under fire from the next line of Americans.

Around midday Izard’s 1,000 troops reached the ravine and lined up to engage 300 dug-in defenders with rolling volleys more suited to a European battlefield than the uneven terrain they faced. A U.S. officer reportedly rode up and ordered Salaberry to surrender, but since the officer was not carrying a white flag of truce, the colonel shot him. In the next three-quarters of an hour of fighting, part of Izard’s force drove back the Canadian Fencibles on Salaberry’s right flank, but reinforcements arrived in time to restore the line. Throughout, Salaberry encouraged a cacophony of bugle calls, cheers, and whoops from the woods to deceive the Americans as to his actual numbers. Allegedly a bugle signal to advance finally convinced Izard that he was outnumbered, and his force retreated three miles.

Just as Purdy reached the point where he hoped to contact Izard and have his wounded ferried across the river, his brigade came under fire from Salaberry’s advance element and spent another wretched night retracing its steps through the forest before finally rejoining Hampton.

At a subsequent council of war Hampton’s adjutant general, Colonel Henry Atkinson, reported 23 men killed, 33 wounded, and 29 missing; Salaberry later accounted for 16 of the latter as prisoners of war, while recording 2 of his own men dead, 16 wounded, and 4 missing. Hampton then withdrew to Four Corners while Atkinson rode off to report the situation to Armstrong.

Arriving at the Châteauguay at the end of the battle, Generals Prevost and de Watteville inflated their role in their dispatches, reporting a brilliant victory by 300 militiamen over 7,500 Americans. Salaberry, furious at their distorted accounts, considered resigning his commission, but the truth stood on its own merits, and he ultimately got due recognition and thanks from the Legislative Assembly of Quebec. Both he and MacDonnell were also made Companions of the Bath.

As Hampton was moving on Montreal, Wilkinson finally got his 8,000-man division underway on October 17. He planned to seize Kingston before joining Hampton, but Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commanding the boats accompanying Wilkinson’s army, vetoed the idea, arguing that the British had a more powerful naval force. Wilkinson’s troops, marching northwest along the Saint Lawrence, reached French Creek (near present-day Clayton, New York) on November 4. There the Americans’ anchorage was bombarded by British brigs and gunboats commanded by Commodore William Howe Mulcaster until Lieutenant Colonel Moses Porter’s artillery drove them off.

On November 6, Wilkinson learned of Hampton’s defeat at the Châteauguay. Dispatching orders for Hampton to march west and join his force, Wilkinson resumed his advance, bypassing Fort Wellington, the British post at Prescott, on the 7th, to land east of Galop Rapids. From there he planned to shoot the Rapids du Plat and the Long Sault Rapids between Morrisburg and Cornwall.

At Kingston, Major General Francis de Rottenburg, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, learned of Wilkinson’s movements from Mulcaster. Although he was primarily concerned with Kingston’s defense, Rottenburg dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Wanton Morrison, the commander of the 2nd Battalion, 89th Foot, to harass the Americans with a 650-man “corps of observation,” consisting primarily of the 89th Foot, the 49th Foot, and a contingent of Royal Artillery. Mulcaster transported the corps as far as Prescott, where the river became too shallow for his largest vessels. Bolstered by the Fort Wellington garrison’s fencible and militia units, as well as three companies of Voltigeurs and 30 Tyendinaga and Mississauga Mohawks, Morrison’s corps grew to almost 900 men as they marched after the largest army yet to invade Canadian soil.

On the evening of November 10, Wilkinson’s vanguard, led by Brigadier General Jacob Jennings Brown, encountered 500 members of the Stormont and Glengarry militia at Hoople Creek, northeast of what is now Morrisburg, Ontario, and drove them off. Meanwhile, Morrison arrived at John Crysler’s farm, just east of Morrisburg, where his troops bedded for the night. The American rearguard, under Brigadier General John Parker Boyd, was encamped just two miles downstream.

November 11 was dawning raw and rainy when a few of Mulcaster’s shallow-draft gunboats fired on Americans encamped at Cook’s Point. Farther inland, a Mohawk shot at an American scouting party, which returned fire, sending half a dozen Canadians rushing back to report that the Americans were attacking. Dropping their half-eaten breakfasts, Morrison’s redcoats stood to arms. This activity likewise roused the Americans to form up for battle.

The rain abated, and at 10:30 a.m Wilkinson got General Brown’s report that his success at Hoople Creek had opened the way to the Long Sault Rapids. Wilkinson, however, wished to eliminate the annoyance to his rear before proceeding. Since he still claimed illness—as did his second in command, Major General Morgan Lewis—Wilkinson delegated the task to Boyd, a veteran of the battles of Tippecanoe and Fort George, heading a detachment of 2,500 soldiers of the 1st, 4th, 9th, 16th, 21st, and 24th Infantry and troops of the 2nd Light Dragoon Regiment.

Despite the muddiness of the open fields, Morrison judged them ideal for the sort of musketry at which his redcoats excelled. While the 500 regulars lined up in the center, supported by two 6-pounder cannons, Morrison anchored his right flank against the Saint Lawrence with Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pearson, Fort Wellington’s commandant, heading a detachment of the light and grenadier companies of the 49th Foot, the Canadian Fencibles and the Canadian Provincial Artillery serving the third 6-pounder, with a gully between them and the Americans. In the woods to the British left, the Voltigeurs, Dundas County Militia, and two dozen Indians took up skirmishing positions.

Boyd, like Hampton at the Châteauguay, sought to flank the British from their left, starting with a thrust by the 21st Infantry that drove the Canadians a mile back through the forest. Pausing for breath, the 21st was then joined by the 12th and 13th Infantry and emerged from the woods on the left flank of the 2nd Battalion, 89th Foot, as planned. Instead of falling back, however, the well-drilled British wheeled about and engaged the Americans with a withering series of volleys that drove them to cover in disorder.

Meanwhile, the U.S. 4th Brigade (9th, 16th, and 25th Infantry), led by Brigadier General Leonard Covington, struggled across the ravine and reached the open field to behold a line of gray-clad soldiers. “Come on, lads,” Covington shouted, “let’s see how you will deal with these militiamen!” Under the gray raincoats, however, were the red coats with green facings of the crack 49th Foot, whose return fire showed why the British called them “the Invincibles” and the Americans would call them “the Green Tigers.” Covington fell mortally wounded, and when his second in command died shortly after, the entire brigade lost order.

At that point Wilkinson’s six cannons belatedly came up the road along the riverbank, unlimbered, and began an effective bombardment. Directed to seize the guns, the 49th Foot advanced in echelon, struggling over several fences and suffering heavy casualties before nearing its objective. In a last effort to save the guns, Colonel John Walbach, Wilkinson’s adjutant general, led the 2nd Dragoons against the 49th’s exposed right flank, but the Invincibles re-formed in time to throw them back. The dragoons charged again, only to be caught in a crossfire between the 49th, Pearson’s detachment, and all three British cannons. At the cost of 18 casualties out of 130 troopers, the dragoons’ sacrifice allowed the artillery to recover five of its guns. The sixth bogged down in the mud and was taken by the 89th Foot.

By 4:30 the Americans were in full retreat, save for soldiers of the 25th and some boat guards covering them until Pearson’s troops threatened to flank them. As darkness fell, the British ended their pursuit while the Americans took their boats to the south side of the river.

If Crysler’s Farm had been an exceptionally conventional pitched battle by the standards of the War of 1812, its butcher’s bill was also exceptionally high. The British lost 31 men killed and 148 wounded; the Americans suffered 103 dead, 247 wounded, and 120 taken prisoner.

On November 12 Wilkinson’s force moved on aboard its boats past Long Sault Rapids to reach a small settlement three miles above Cornwall, where it reunited with Brown’s vanguard. Colonel Atkinson arrived to report Hampton’s decision to retire to Plattsburgh, and Wilkinson held another council of war, which unanimously agreed to curtail the campaign. He withdrew to French Mills and then, with supplies running low, to Plattsburgh.

Wilkinson planned additional invasions that winter, but his only offensive move, with 4,000 troops, was thwarted by 80 defenders and 420 reinforcements at Lacolle Mills on March 30, 1814. Wilkinson had previously asked a court of inquiry to evaluate his performance on March 24, and he received its appraisal on April 11, when he was relieved of command. Although in another court-martial he evaded conviction for negligence and misconduct, his career in the U.S. Army was over.

Lewis was also retired, and Boyd was sidelined to rear-area commands as Armstrong began winnowing the senior ranks and refilling them with younger men of recently proven merit, such as George Izard (who replaced Wilkinson), Jacob Brown, and Winfield Scott.

Although the humiliating Saint Lawrence campaign is given short shrift in American histories of the War of 1812, it is better remembered north of the border, where Crysler’s Farm is known as “the battle that saved Canada.” Even more legendary is the Châteauguay, in which an army of U.S. Army regulars met ignominious defeat at the hands of a small group of local militiamen of English, Scottish, French, and First Nations, a cross-section of peoples who would compose, 54 years later, the Dominion of Canada.