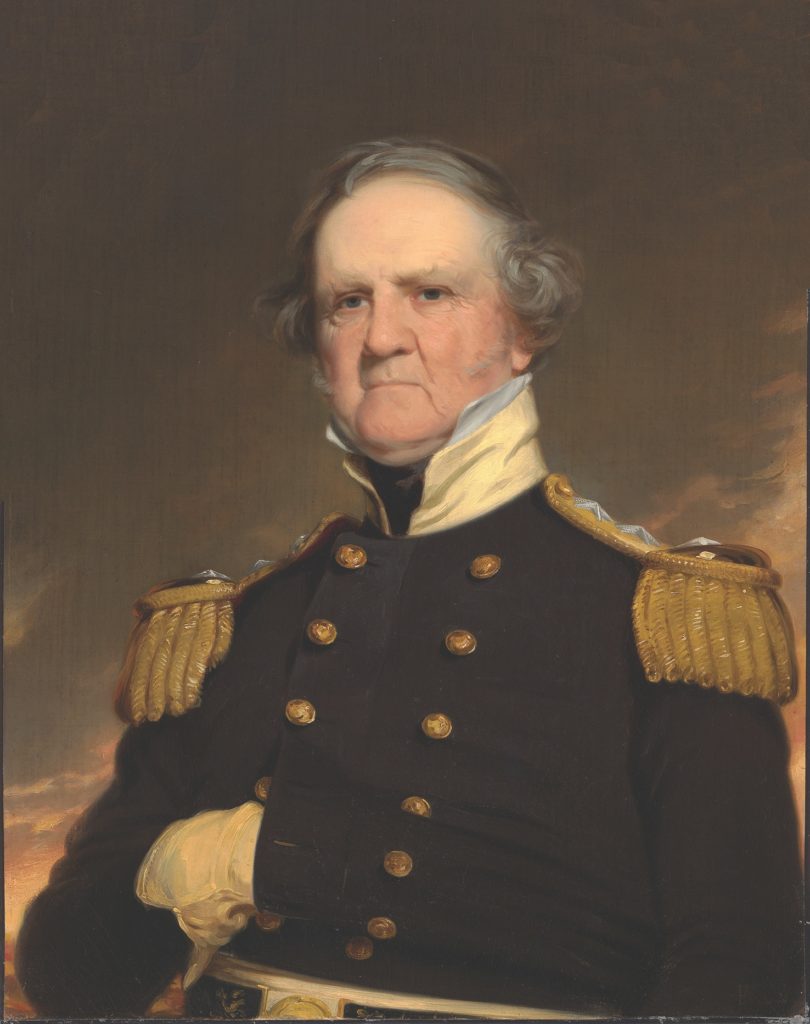

His experiences in the War of 1812 and subsequent six-week captivity in Canada opened his eyes to the need for a professional regular army.

It was the sort of message no soldier ever wants to receive, particularly not an untried 26-year-old U.S. Army officer leading his men as they confronted a disciplined and heavily reinforced British opponent. On the afternoon of October 13, 1812, Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott opened the note from his commanding officer, Major General Stephen Van Rensselaer. “I have passed through my camp,” Van Rensselaer advised him. “Not a regiment, not a company is willing to join you. Save yourself by a retreat, if you can.”

Just a few hours earlier Scott had crossed the 250-yard-wide Niagara River to take charge of a ragtag force of regulars and militia on the heights overlooking the Canadian hamlet of Queenston, Ontario. Shortly after he arrived, Scott realized that the British force spread out before him was being heavily reinforced. From a strategic standpoint, Scott’s men had a good position on the heights, but with no re-inforcements of his own, the prospects for holding it were rapidly evaporating. Concluding that nothing more could be accomplished on Canadian soil that day, Scott led his men down the steep bank to the river but found no boats waiting to take them back across to American soil.

The problem wasn’t that Van Rensselaer had no men to send to Scott. It was that some of the militia units still on the New York side of the Niagara River had refused to follow their comrades into Canada, a refusal that Scott laid squarely on “the machinations in the ranks of demagogues.” The malcontents had argued that since they belonged to the New York militia, they were free to disregard orders to operate outside the state, effectively denying their commander’s authority over them. After feebly attempting to convince them otherwise, Van Rensselaer decided that he had no choice but to acquiesce. They stayed where they were, and Scott and his men were marooned on the other side of the river.

Scott could barely contain his abject contempt for the New Yorkers, characterizing them as “vermin who no sooner found themselves in sight of the enemy than they discovered that the militia of the United States could not be constitutionally marched into a foreign country.” Scott’s experiences in the Battle of Queenston Heights, in fact, left him with a lifelong disdain for amateur citizen-soldiers and a concomitant attachment to the professional soldiers in the regular army—the “rascally regulars,” as he affectionately called them. That mindset would prove to have a far-reaching effect on the future of American arms.

For the moment, though, Scott faced a more immediate problem. British infantry and artillery, supported by some 300 Mohawk Indians, had completely routed the American militia, which surrendered en masse at the edge of the river. Scott, his senior officers, and their remaining regular troops waited in vain for boats to cross the water to evacuate them. Finally, with Mohawk warriors furiously shooting at them to avenge the deaths of two of their war chiefs, Scott surrendered to British major general Roger Hale Sheaffe. On surrendering, Scott was astonished to see another 500 American militiamen emerge from hiding on the heights above and surrender also.

Sheaffe immediately paroled the American militia units across the river, perhaps assuming that no further trouble could be expected from them. Scott and other members of the regular army were transported to Quebec to witness the burial of British major general Sir Isaac Brock, who had been killed by a musket ball at Queenston Heights. Scott and his comrades were sent to Kingston and down the Saint Lawrence River to Montreal, where British governor Sir George Prevost ordered them to march in front of his garrison troops, which were drawn up in line of battle. Prevost, Scott would later write, subjected the Americans to other “slights and neglects which excited contempt and loathing.” Scott and his men were then taken to Quebec and put under the charge of the far more courteous and respectful major general George Glasgow.

Scott’s subsequent six-week captivity in Canada gave him the opportunity not only to reflect on the shortcomings of his own country’s army but also to observe how the men who had defeated him handled their business. He could not help but be impressed. With the exception of Prevost’s effort to embarrass the Americans at Montreal, Scott deemed the conduct of Glasgow and other British regular officers to have been exemplary. He saw at close hand the culture of discipline, service, and duty that characterized the British regular army and the proficiency and dependability with which British regulars of all ranks performed their duties.

Once exchanged, Scott returned home determined to change how the United States trained and deployed its land forces. Promoted to full colonel in the 2nd U.S. Artillery, in May 1813 Scott returned to the frontier and led a successful attack, in cooperation with American naval forces, that resulted in the capture of Fort George on the Niagara River. In March of the following year he was promoted to brigadier general and put in charge of organizing and training the American forces at Buffalo, New York. Applying the tactical, organizational, and administrative lessons he had learned from his large collection of history books as well as from his British captors, he pledged to make his force the best in the American army. He spent long hours drilling his officers and men at a training camp he established at Flint Hill.

For two months the men were drilled 10 hours a day, seven days a week. Scott had a fanatical eye for detail; drills were conducted by squads, companies, regiments, and brigades—the last put through their paces by Scott himself. No detail, however humble, was overlooked: Scott even specified how bread should be baked, where latrines should be located, and how frequently the men should bathe. In a break with tradition, he stressed discipline through professional pride rather than fear of physical punishment. Officers who struck enlisted men were suspended from duty. The lack of standard drill and tactical manuals complicated Scott’s efforts, and he vowed to oversee the writing of a new manual after the war was over. In the meantime, since Scott could read and write French, he used a French training manual to drill the men.

That summer, Scott and his command crossed the Niagara River and took part in the Battles of Chippawa and Lundy’s Lane, where he was seriously wounded in the shoulder. Phineas Riall, a British officer at the former engagement, was so impressed with the conduct of Scott’s command that he reportedly cried out in astonishment, “Those are regulars, by God!”

Scott’s success validated his emphasis on discipline and leadership, providing a model for other regular army units and leaving little doubt as to their superiority over the militia on the battlefield. Indeed, there was a conspicuous contrast between the success of Scott’s forces along the Niagara frontier and the disastrous performance of militia forces charged with defending Washington, D.C., later that year. In the immediate aftermath of that debacle, Scott tirelessly sought support for reforms that would professionalize the regular army and ensure its unquestioned preeminence over the militia.

In doing so, Scott was bucking a long tradition of American support for part-time militias made up of citizen–soldiers. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington had demonstrated the importance of having a well-maintained and technically proficient regular army play the lead role in American defense. But many Americans disagreed with Washington. They believed that every son of the republic had the qualities necessary to be an effective soldier. They were bitter about the conduct of the British red-coated regulars and angry about centralized authority and increased taxes. In 1784, responding to the popular will, congressional lawmakers reduced the standing army to a force capable of little more than guarding military stores.

A few years later, however, Shays’s Rebellion—an armed uprising in Massachusetts against local taxing and judicial authorities—triggered new calls for a stronger central government. Washington and his allies took advantage of the new political climate to write and ratify the Constitution of 1787, which pressed for a more robust national army. Still, many common Americans opposed efforts to strengthen the central government and the nation’s standing army, sentiments that helped propel Thomas Jefferson to a decisive victory in the 1800 presidential election over incumbent President John Adams.

It was during Jefferson’s presidency that Winfield Scott first entered the U.S. Army, accepting a commission as a captain in 1808. His initial experiences in the army gave him little confidence in its abilities. With next to no guidance, Scott was expected to recruit the men who would fill the ranks of his command, and his fellow officers hardly inspired confidence. The veterans struck Scott as “coarse and ignorant, sunk into either sloth…or habits of intemperate drinking,” and the new officers seemed “utterly unfit for any military purpose whatever.” Scott was so disgusted that he strongly considered resigning. While serving in Louisiana he fought a duel with a fellow officer—each fired at the other, a bullet grazed Scott’s scalp—and Scott was court-martialed and suspended for a year over minor financial irregularities and his intemperate remarks concerning his commanding general, James Wilkinson. But Scott returned to active duty in 1810 and served through the inconclusive end of the War of 1812.

The final battle of the war, at New Orleans, presented a strong challenge to Scott’s concept of a professional standing army. There, Major General Andrew Jackson, an old Indian fighter and self-taught soldier, led a motley force of frontier militiamen, Gulf Coast pirates, and freed Blacks to a stunning victory over elite British regulars. Scott immediately realized the challenge. “Jackson and the Western militia,” he warned, “seem likely to throw all other generals and the regular troops into the background.” Another frontier–schooled general, Edmund Pendleton Gaines, entered the fray, insisting that “the brave people of the West need no other preparation than what their own strong arms, good rifles, and sound hearts will at the moment furnish.”

Scott believed that while citizen-soldiers could provide manpower when the nation went to war, the regular army needed well-led officers who had professional expertise and adhered to formal standards of conduct in the execution of their duties. To create such leaders, Scott and like-minded other officers and politicians decided the U.S. Military Academy at West Point needed some improvements. In 1817 they installed as its superintendent Sylvanus Thayer, who had graduated from Dartmouth College a decade earlier as the valedictorian of his class and proceeded to graduate from West Point after a single year. In the decades that followed, Scott would be a frequent visitor to West Point, providing cadets and officers with a personal example of professional proficiency, attention to standards, and commitment to the regular army as an institution. He also fulfilled a longstanding promise by writing a three-volume training manual—Infantry Tactics, Or, Rules for the Exercise and Manoeuvres of the United States Infantry—that until 1855 served as the U.S. Army’s standard drill manual.

Scott’s ultimate personal and professional triumph came in his brilliantly conducted landing at Veracruz and subsequent 300-mile overland march and capture of Mexico City during the Mexican-American War in 1847. No less an authority than the British victor at the Battle of Waterloo, the Duke of Wellington, termed Scott’s campaign “unsurpassed in military annals” and labeled Scott “the greatest living soldier.” Scott, for his part, credited to that bastion of military professionalism, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point: “I will say to my dying bed that but for the Military Academy I never could have entered the basin of Mexico.”

Scott’s Mexican victory epitomized the canny observation by German chancellor Otto von Bismarck that “a generation that has taken a beating is always followed by a generation that deals one.” But Scott’s achievement was not universally praised. Even the president of the United States at the time, James K. Polk, underplayed it. “The gallant American soldiers could have won the war,” Polk said, “if there was not an officer among them.”

For the rest of his life, Scott struggled against grandstanding politicians who appealed to the popular mythology of the citizen-soldier and complained that the military academy and the regular army’s officer corps fostered European attitudes toward war and the military that were contrary to the spirit of republican government. In the meantime, Scott watched fellow generals Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and Zachary Taylor exploit their images as frontier fighters and their homespun nicknames—“Old Hickory,” “Old Tippecanoe,” and “Old Rough and Ready,” respectively—to win the presidency. In contrast, Scott’s demands for attention to detail and adherence to professional standards in dress and conduct saddled him with the unflattering sobriquet “Old Fuss and Feathers” and undermined his own bid for the presidency in 1852.

Nevertheless, Scott ultimately succeeded in determining how the nation’s ground forces would be led. West Point graduates and products of the regular army would command both the great armies of the Civil War. His “Anaconda Plan” to win the war for the Union by blockading Confederate coasts and seizing control of the major inland rivers, although frequently ignored or superseded by events, eventually proved prescient. His influence would also be evident in William Tecumseh Sherman’s postwar labors as commanding general of the army. These included the establishment of a school at Fort Leavenworth for the development of regular officers and support for military theorist Emory Upton’s intensive studies of foreign armies and America’s own military history, which made a renewed case for Scott’s vision of a robust army of regulars led by professional officers.

While failures of administration by the army during the Spanish-American War served as a catalyst for change (even as Teddy Roosevelt’s well-publicized exploits in Cuba boosted the image of the amateur soldier), subsequent reforms only confirmed the preeminence of the regular army. When the United States went to war in 1918 and again in 1941, it mobilized millions of citizen-soldiers, but in both instances they would be commanded by regular officers. And even though post–Vietnam War reforms sought to better integrate the reserves and National Guard into the wartime force, Scott’s vision of American land forces firmly in the hands of the regular army has largely been realized.

It could all be traced to a few chaotic hours in October 1812 on the bluffs overlooking Queenston Heights and the Niagara River, when a haughty young officer snatched the lessons of command and professionalism from the jaws of defeat. While Queenston Heights was by no means the first or last time that American forces took a beating, no other American military defeat—not Bunker Hill, First Bull Run, Little Big Horn, Kasserine Pass, or Task Force Smith in the Korean War—would have a more profound or enduring effect on the future of the American military, beginning with the untried lieutenant colonel who endured that beating and, more important, learned from it. MHQ

Ethan S. Rafuse is a professor of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2020 issue (Vol. 33, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Behind the Lines | The Education of Winfield Scott

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!