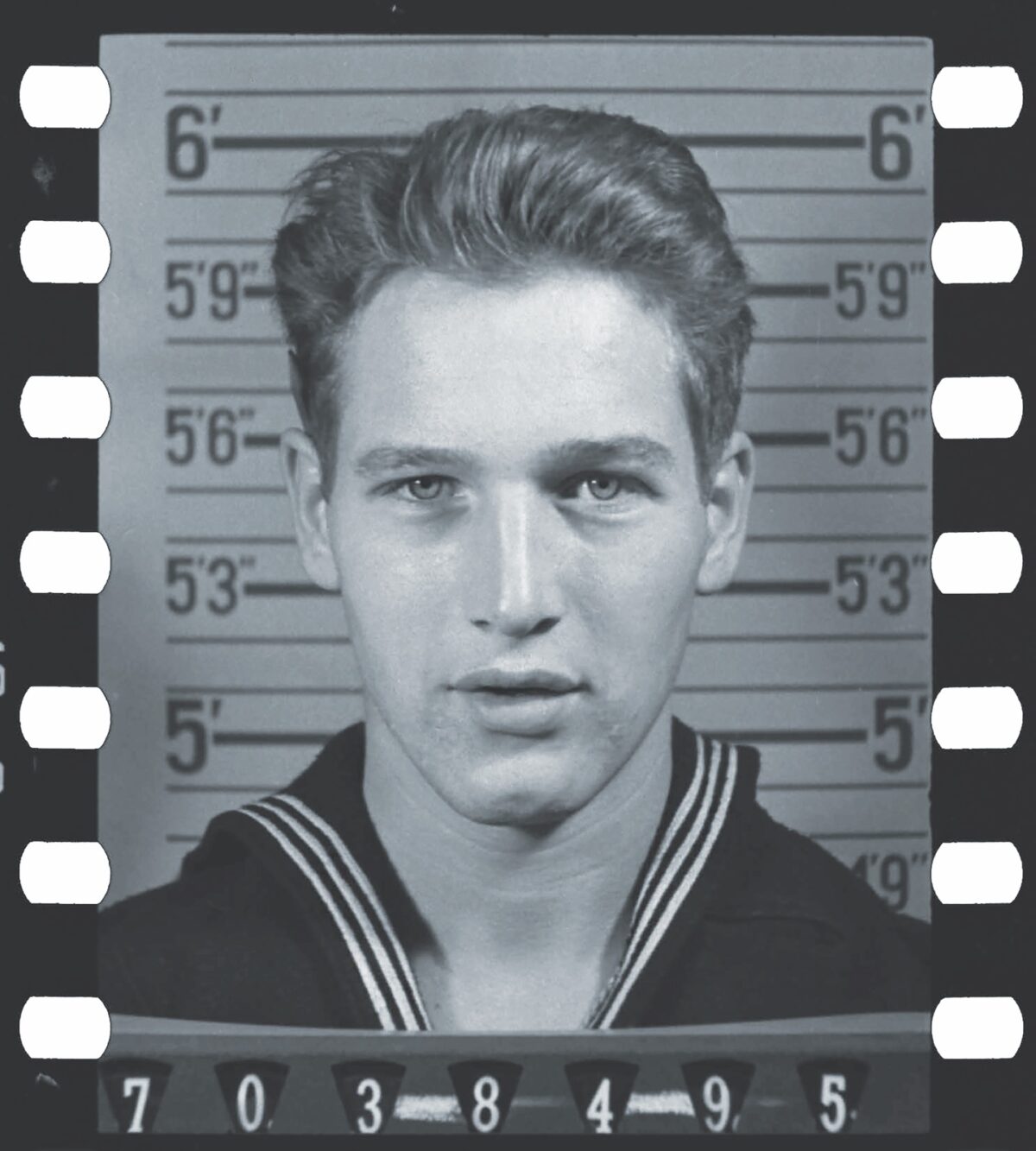

Noah Worcester

In the spring of 1775, with the redcoats storming Boston, 16-year-old Noah Worcester joined his father’s company of New Hampshire militiamen on their trek south to team up with the patriot army assembling in nearby Cambridge. Weeks later, as the Siege of Boston continued, Worcester served as a fifer at the Battle of Bunker Hill, where he narrowly escaped capture by British forces, and went on to complete 11 months of service in the Revolutionary War. He rejoined the patriot army for a two-month stint as a fife major in the summer of 1777 and took part in the victory at the Battle of Bennington. Its deadly aftermath spurred him to embrace pacifism and, in the process, kindle the American peace movement. Worcester went on to become a liberal clergyman in the Boston area, where he founded the Massachusetts Peace Society; launched and edited the influential quarterly Friend of Peace; and, in 1814, published the book (under the pseudonym Philo Pacificus) A Solemn Review of the Custom of War, still celebrated as a groundbreaking and enduring pacifist manifesto.

in the Crimean War. (Bridgeman Images)

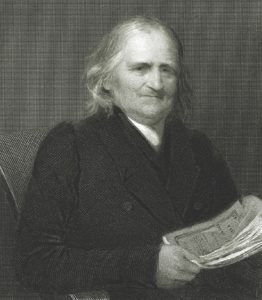

Leo Tolstoy

The celebrated novelist Count Lev (Leo) Nikolayevich Tolstoy was born in 1828 on his family’s estate a hundred miles south of Moscow. Following years at university, distinguished largely by his fondness for partying, Tolstoy returned to his deceased parents’ estate, where he proved to be inept at farming and even worse at gambling, running up sizable debts. In 1851 his older brother Nikolay urged Leo to join him in the army; the aimless younger brother soon signed up and headed to the Caucasus Mountains. In November 1854, Tolstoy was transferred a thousand miles east to Sevastopol, Ukraine, where the young artillery officer spent nine months fighting in the Crimean War. But while Tolstoy’s courage earned him a promotion to lieutenant, his unsettling battlefield experiences also informed his famous antiwar writings and his strict, decadeslong embrace of pacifism, which was rooted in his religious beliefs rather than his moral misgivings, and which inspired global social movements dedicated to everything from spiritual reflection to vegetarianism. In fact, The Kingdom of God Is within You, Tolstoy’s philosophical treatise published in 1894, had a profound influence on such high–profile proponents of nonviolent resistance as Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

Smedley Butler

Though Smedley Darlington Butler was born into a Pennsylvania Quaker family in 1881, he dropped out of school weeks before his 17th birthday to join the U.S. Marine Corps. Butler was soon appointed a second lieutenant, and with that, “Old Gimlet Eye,” as he would come to be known, began a military career that few leathernecks have matched. With postings that spanned the Spanish-American War in Cuba and the Boxer Rebellion in China to the Western Front of World War I and the Marine Corps Base in Quantico, Virginia, where he was commanding general, Major General Butler received the Distinguished Service Medal for both the army and the navy and was one of just two marines to garner Medals of Honor for two separate acts of outstanding heroism. But following his retirement, in 1931, Butler wrote War Is a Racket, a short book that grew out of a series of speeches before churches and pacifist groups all across the nation. Butler passionately criticized U.S. war efforts as both imperialistic and designed to enrich well-heeled profiteers who never shouldered a rifle. War, he wrote, is the only enterprise “in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives.”

Claude Choules

In August 2011, Australian officials announced that the Largs Bay, a dock landing ship that the Royal Australian Navy had recently purchased, would be renamed in honor of Chief Petty Officer Claude Choules, who had died earlier that year in a nursing home. At the time of his passing, the English-born “Chuckles” Choules, 110 years old, was the last known surviving service member of World War I. He had joined the British Royal Navy shortly after his 14th birthday, and in 1918, from the battleship HMS Revenge, he watched the surrender of the German High Seas Fleet. Choules later transferred to the Royal Australian Navy, and during World War II he served his adopted nation as an antisubmarine instructor and chief demolition officer; he finally retired from the Australian navy in 1956. Despite his lengthy wartime service, Choules was hardly enamored of the military. He became a pacifist and purposely steered clear of the annual Anzac Day parades honoring those who served and died in war. In fact, he refused to even discuss anything about that glorified war. “There was definitely no glory in it from his point of view,” his grandson told Time magazine. “He firmly believed that war was a pure waste of time, resources, and human life.”

Albert Bigelow

Albert “Bert” Bigelow, born in 1906, was endowed at birth with brains (later earning degrees from Harvard and M.I.T.), brawn (he was a hulking college hockey player), and, by all evidence, a destiny to be shaped at sea. During World War II, Bigelow served as commander of a U.S. Navy submarine chaser and later as captain of the destroyer escort USS Dale W. Peterson. In early August 1945, as DE-337 streamed into Pearl Harbor, Bigelow was on the bridge when news arrived of the atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima. “It was then,” he later wrote, “that I realized for the first time that morally war is impossible.” In fact, Bigelow went on to become a pacifist and committed antiwar activist: In early 1958, he twice captained a 30-foot ketch, The Golden Rule, toward nuclear-bomb testing grounds in the Marshall Islands to protest atomic warfare, only to be intercepted near Hawaii by the Coast Guard and jailed for his news-making actions.

George McGovern

In January 1942, weeks after Japanese war planes launched a surprise bombing attack at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, college sophomore George McGovern, who had already earned his pilot’s license, volunteered to join the American armed forces. When he was finally called for service, more than a year later, the South Dakota native was trained to fly the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, a hulking four-engine bomber alternatively known as the Flying Boxcar and the Flying Coffin. Beginning in late 1944, McGovern flew three dozen missions over European countries as part of a strategic bombing campaign designed to take out enemy oil refineries and railyards, his heroics earning him a rank of first lieutenant and a Distinguished Flying Cross. But the future U.S. representative, senator, and presidential candidate would go on to forge a legacy born of his anti–Vietnam War crusade, spearheading a high-profile campaign to end the conflict primarily by legislative means. “Every Senator in this chamber is partly responsible for sending 50,000 young Americans to an early grave,” he once proclaimed in floor debate. “This chamber reeks of blood.”

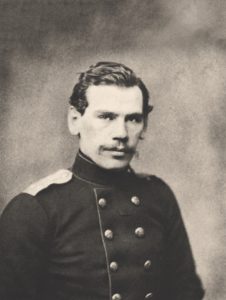

Paul Newman

Decades before he was the Hustler or Cool Hand Luke, Paul Newman was known as Aviation Radioman Third Class, his three years of service in the U.S. Navy during World War II ending in 1946. Newman aspired to be a pilot, but his color blindness stood in the way. He was instead assigned to torpedo bomber squadrons and later served as a turret gunner in a Grumman TBF Avenger flying from aircraft carriers. After the war, Newman studied at the Yale School of Drama and the fabled Actors Studio in New York City, and he went on to parlay his brilliant blue eyes and leading-man looks into a legendary career on the stage and screen as well as in auto racing. But Newman also garnered notoriety far from Hollywood lots as an avid promoter of antiwar and social justice causes, and in 1971 his fervent opposition to the Vietnam War landed him on President Richard Nixon’s “enemies” list. Seven years later, Newman would serve as one of five U.S. representatives to the United Nations General Assembly’s Special Session on Disarmament.

Abie Nathan

Abie Nathan was born in 1927 to Jewish parents in the Persian city of Abadan, which today is in southwestern Iran. The family moved to Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1939, and four years later the 16-year-old student lied about his age and was drafted into a pilot-training course with the Royal Air Force. He later began training as a bomber pilot, but he left the armed forces before seeing combat and was recruited by Air India—a career move that was soon interrupted to fight with some 4,000 other foreign volunteers (the Machal) in Israel’s 1948 war of independence. Nathan served alongside Israeli forces as a combat pilot, bombing army forces and Arab villages—missions whose resulting carnage would one day spur him to become an internationally recognized advocate for peace, most notably between Israel and Arab nations. To that end, in 1966 he defied the Israeli Air Force and flew his “peace plane” to Egypt in hopes of encouraging dialogue between the two nations. He met with religious and political leaders around the world to promote peace. And along with numerous global antiwar and relief efforts, in the 1980s he operated a pirate radio station, the Voice of Peace, that broadcast throughout the Middle East from his Peace Ship, a reconfigured coastal freighter that sat just beyond Israel’s territorial waters.

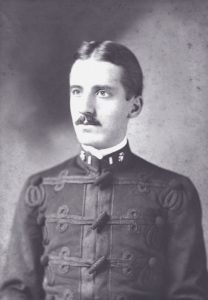

Andrew Jacobs Jr.

After he graduated from high school in 1949, Andy Jacobs joined the U.S. Marine Corps, his rationale that his dress blues would be just the ticket to finding a weekly date. A year later, however, with the outbreak of the Korean War, the Indianapolis native would instead be suited up for combat, as his infantry unit was dispatched to Pusan, near the 38th Parallel. During his tour of duty, which ended in 1952, Private Jacobs was wounded in action, fought in the battle of Ka-san (aka Hill 902), and miraculously sidestepped death when two armed Chinese soldiers allowed him and other marines to pass by with a stretcher bearing their wounded lieutenant. Jacobs was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives a dozen years after his discharge, where he was an early opponent of the Vietnam War (and every war thereafter, all of which he deemed unconstitutional), and a strong supporter of the Religious Freedom Peace Tax Fund Act, which would permit citizens to designate their tax payments for nonmilitary purposes. But “the conscience of the House,” as Ralph Nader dubbed him, may be best remembered for two phrases he coined in a 1999 memoir: “war wimps” and “chicken hawks”—those eager to send others to battle while never serving themselves.

Jimmy Carter

On graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1946, James Earl Carter Jr. was commissioned as an ensign and served as a surface warfare officer in the Atlantic and Pacific Fleets. He then volunteered for submarine duty, eventually qualifying to be a sub commander and, in 1952, earning the rank of lieutenant. That same year, Admiral Hyman G. Rickover selected Carter for the fledgling nuclear submarine program, and Carter set his sights on working aboard the planned USS Seawolf. But following his father’s death in 1953, Carter resigned from active duty to run his family’s Georgia-based peanut-growing business. Two decades later, the 39th president of the United States governed like a lifelong dove: He pardoned all Vietnam War draft dodgers, halted development of the neutron bomb, and, against all odds, forged a Middle East peace treaty. He waged no wars while in office—a first for an American commander in chief. Moreover, the Carter Center, which he founded in 1982, won the Nobel Peace Prize 20 years later.

Donald Duncan

Donald Walter Duncan, a naturalized U.S. citizen born in Toronto in 1930, was drafted by the U.S. Army in December 1954 and the following summer was dispatched to Germany, where he ultimately served with an artillery unit as a noncommissioned officer in operations and intelligence. Duncan returned to U.S. soil in late 1957, where he later served with Special Forces until he volunteered for deployment in South Vietnam in the spring of 1964. Over 18 months in combat, he helped establish and then run Project DELTA special reconnaissance units—eight-man “hunter-killer” teams that did everything from enemy interrogations to commando raids. For his efforts, Master Sergeant Duncan received Bronze Star Medals for both heroism and meritorious service, along with other citations. But Duncan had grown disillusioned with American policies well before his discharge in September 1965, and on returning home he became an early and prominent critic of the country’s war efforts. For example, in a 1966 cover story for Ramparts magazine titled “The Whole Things Was a Lie!,” the decorated Green Beret wrote of antiwar protesters: “They are not unpatriotic….They are opposed to people, our own and others, dying for a lie, thereby corrupting the very word democracy.”