An accomplished Roman naval commander, Marcus Aurelius Mausaeus Carausius became an outlaw, carved out his own kingdom and defied the empire he once served. Joining forces with Germanic sea raiders who were formerly his enemies, Carausius was vilified in ancient texts and perceived as so dastardly by some Roman historians that they refused to even mention his name.

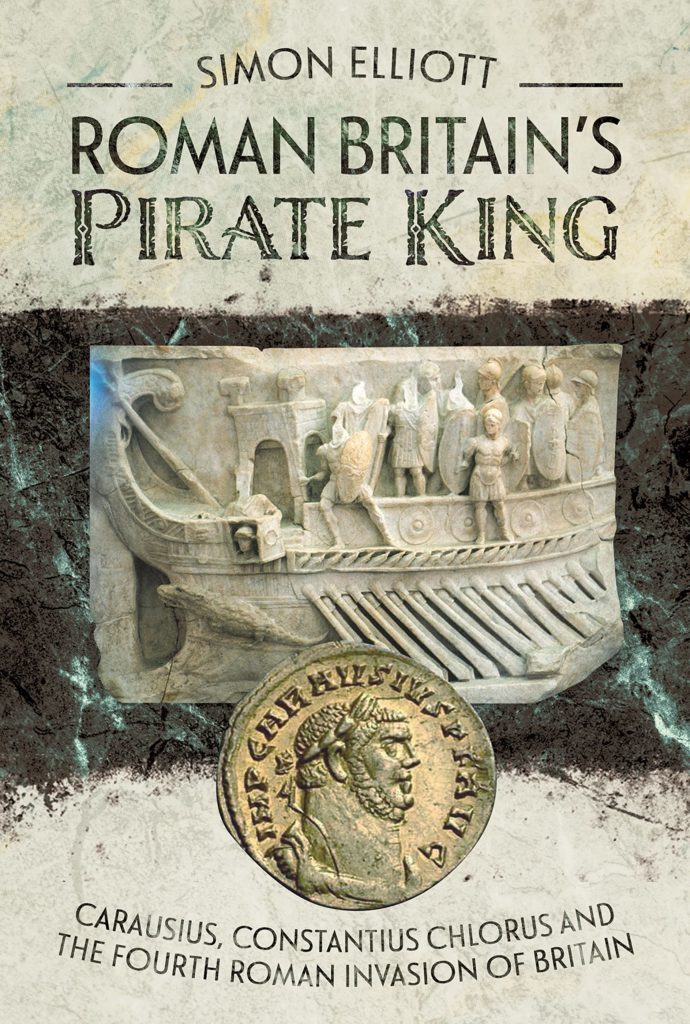

Roman military expert and archaeologist Simon Elliott has reinvestigated the legacy of Carausius in his forthcoming book, “Roman Britain’s Pirate King: Carausius, Constantius Chlorus and the Fourth Roman Invasion of Britain,” to reveal the man behind the myth.

In his groundbreaking study of Carausius, Elliott relates that, far from being a common criminal, Carausius was actually a savvy military commander who won the loyalty of local legions, gained control of waterways with critical strategic importance, and shaped civilization in Roman Britain.

In an interview with Military History Quarterly, Elliott sheds some light on his research into the life and leadership of Roman Britain’s enigmatic “pirate king.”

How did you become interested in the story of Carausius?

Carausius is actually a key figure in British history, originally lost in the mists of time because he took on the Roman imperial center in the form of the emperors Maximian and Diocletian, ultimately lost, and was effectively cancelled by them.

Some Roman writers even refuse to mention his name, simply calling him a pirate. He came back into focus through the investigations of antiquarians who noticed the vast number of Roman coins found in Britain which he minted – not surprising in retrospect given he actually created Roman Britain’s first mint.

I found his story fascinating and therefore decided to dig deeper, finding every single contemporary reference about him. I then set this against the latest archaeological data and was able to write this biography of him – the first.

Popular imagination tends to associate pirates with the so-called Golden Age of Piracy from 1650 to 1720, rather than ancient times. What was life like for pirates in the Roman Empire?

Piracy was endemic in the ancient world, famously in the context of Julius Caesar who was captured by Cilician Pirates on his way to Rhodes, and earlier Pompey the Great who made his name defeating such Anatolian pirates.

Interestingly, the use of the term by the imperial center against Carausius was designed to diminish him. In reality he was actually a usurper who established his North Sea Empire in northwestern Gaul and Britain after Maximian accused him of being in league with the Germanic North Sea raiders he had successfully defeated.

It seems that Carausius was on a mission from Rome to defeat pirates before he ended up becoming one himself. Can you tell us more about his transformation from naval commander to outlaw?

He was already a successful military commander on land, helping the western emperor Maximian defeat German incursions across the Rhine frontier. He was also an experienced naval commander. His home territory was in the lands of the Menapii in the Rhine Delta. To that end he was an obvious choice in AD 286 for Maximian to appoint his new naval commander when he needed to rid the North Sea of endemic German piracy after the British regional fleet (the Classis Britannica) had ceased to exist earlier in the century.

However, Carausius proved so successful that many at court grew jealous and began to turn the emperor against him.

Eventually word reached Carausius that he had been sentenced to execution for pocketing the loot he had recovered from the Germans, and he had no choice but to usurp, becoming an outlaw (albeit on the grandest scale) himself.

Carausius began his career as the commander of a Roman fleet. After he turned to piracy, did Roman citizens continue to serve under him in any large capacity, or did he primarily rely on locally recruited foreigners known to the Romans as “barbarians”?

Bit of both. In an ancient world sense he was fabulous at his own PR – a real-life imperial spin doctor in fact. For example, he minted thousands of very high-quality silver and gold coins with much higher precious metal contents than those of Maximian or Diocletian to show that he was there to restore the glory days of empire in northwestern Europe. To reinforce this message many carried traditional classical texts, for example from Virgil.

It seems this worked, with the legions in the region initially supporting him. However, later, when the imperial centre began to regain ground, he had to increasingly rely on mercenaries. After his assassination by his deputy Allectus in AD 293 after he had lost Boulogne-sur-Mer, the man who usurped his role had to completely rely on German mercenaries.

What kind of leader was Carausius, and why did he attract followers?

A fabulous inspirer of his followers. You can’t underestimate the jeopardy faced by senior military leaders and nobles in Roman northwestern Europe when faced with the choice of supporting him or not, especially after the similar Gallic Empire of Postumus had collapsed only 12 years earlier.

Back the wrong horse and you and your family were dead, with your lands confiscated by the emperor. So to convince these people to support him was no mean feat.

Carausius laid claim to a North Sea Empire. How did he create this empire?

In simple terms, by convincing the military and nobles in northwestern Gaul and Britain to support his usurpation.

Carausius successfully repelled attacks by imperial troops. What were the most important waterways he had access to, and did control of any of these features play a significant role in helping him defeat his Roman enemies? If so, how?

Carausius’ new fleet, which he used to defeat the Germanic pirates in the North Sea and then later to defend his breakaway empire against the Roman’s themselves, would have controlled the same maritime areas as the earlier Classis Britannica.

This would have included the North Sea, English Channel, Atlantic Approaches, Irish Sea, the littoral coastal zone around the main island of Britain, Britain’s river systems, and also the continental coastline from the Bay of Biscay up to the Rhine Delta.

Was it difficult to research his story, and if so, can you tell us about what materials you explored to find out more about him?

Contemporary sources from the later Roman Empire are important here, though of course given they are written for an imperial audience after the event they are all anti-Carausian, which of course I took into account.

There are also some important panegyrics written for Maximian, Constantius Chlorus and Constantine I which are also insightful, but again negative. That is why, in researching this story, the archaeology is so important, to not only help date events but to provide balance.

You are an expert in ancient Roman history and are familiar with many topics concerning military life in the ancient world. Did you make any surprising discoveries, and if so, what were they?

Yes, namely that the final phase of public building in Roman Britain dates to Carausius and Allectus. This includes a huge government building complex in western Londinium, the river wall of Roman London, and the later Saxon Shore forts.

These include those at Richborough, Lympne, Dover, Pevensey and Portchester. Further, many of these were built from recycled materials from demolished earlier public buildings and mausolea.

How long did Carausius control Britain, and in what ways did his rule shape the early history of the British Isles?

The North Sea Empire lasted from AD 286 to AD 296. The first seven years were under Carausius’ rule before he was assassinated by Allectus. Then he [Allectus] ruled for three years before his final defeat by the western caesar Constantius Chlorus.

Crucially, I argue that before Carausius’ usurpation, the imperial center was growing weary of troublesome Britain, but having committed to recapturing it from Carausius and Allectus (so as not to lose face) it was then not an option to leave in the short term.

So the revolt kept Britain on the imperial map for another century at least!

Roman Britain’s Pirate King

Carausius, Constantius Chlorus and the Fourth Roman Invasion of Britain

by Dr. Simon Elliott, Pen & Sword, September 2022

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.