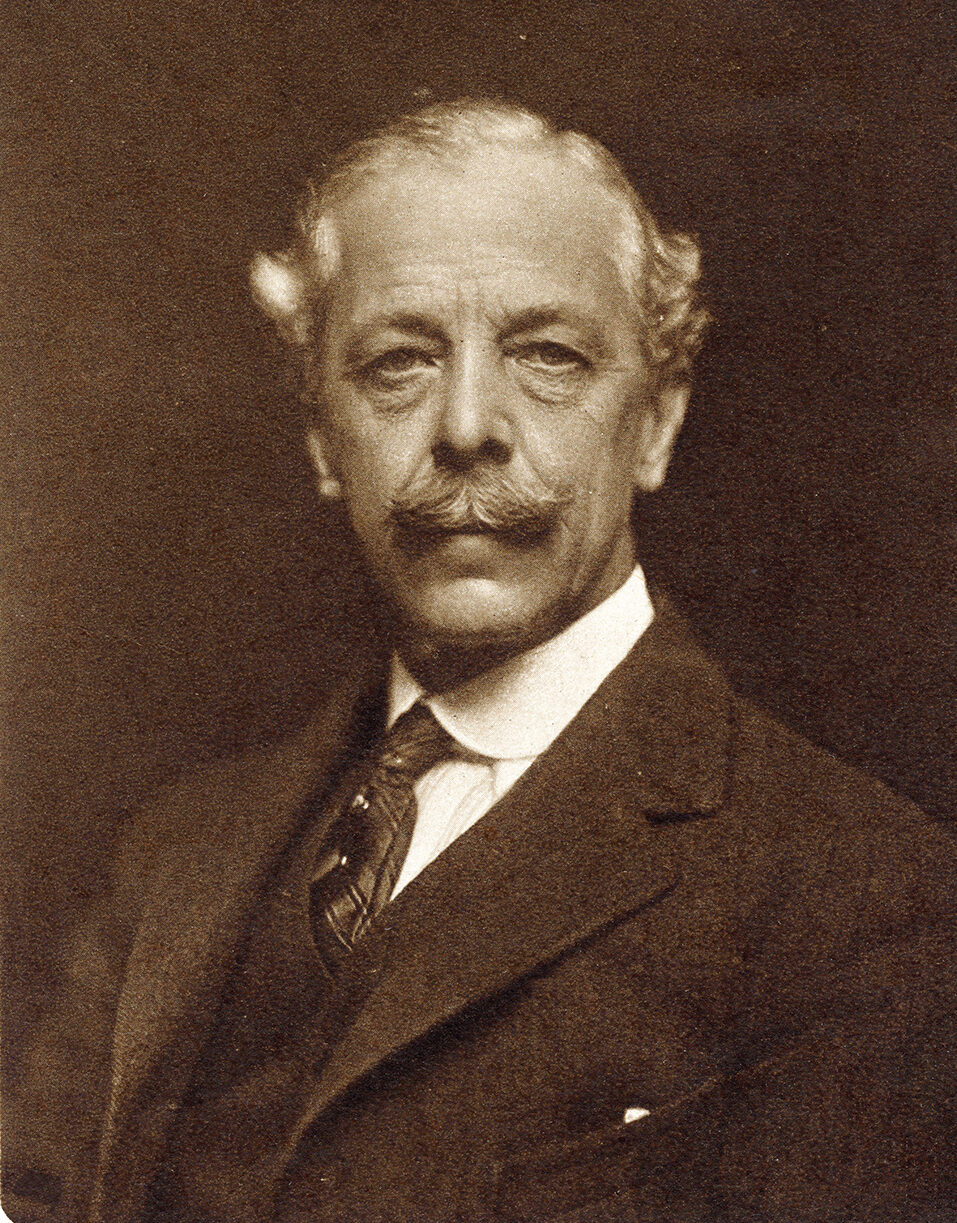

British naval historian and geostrategist Sir Julian Corbett (1854–1922) was a contemporary of renowned American naval strategist Rear Adm. Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840–1914). Unlike Mahan, Corbett had no personal military or naval experience, which prompted many senior officers in the Admiralty to view him and his theories with skepticism. A misconception persists that the ideas of Mahan and Corbett are in opposition, that one must accept one or the other. But that is an oversimplification. There is much to be learned by a comparison of the two.

In developing a set of principles for naval warfare, Corbett drew from the theories of land warfare developed by Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz. On the relationship between war and politics he echoed Clausewitz: “Military action must still be regarded only as a manifestation of policy. It must never supersede policy. The policy is always the object; war is only the means by which we obtain the object, and the means must always keep the end in view.”

In defining essential differences between the respective physical operating environments of land and sea, however, Corbett departed from Clausewitz on key points, particularly the importance of concentration and the decisive battle. Control and security of communications, for example, is far more difficult at sea. Communications on land are largely limited to known roads, rail lines and rivers and channelized by mountains, forests and other no-go terrain. Predicting communications and movement on a vast, flat ocean is an entirely different matter. “At sea the communications are, for the most part, common to both belligerents,” Corbett noted, “whereas ashore each possess his own on his own territory.” Thus, he concluded, only relative command of the sea was possible at any given place and time.

Corbett departed from both Mahan’s and Clausewitz’s argument for the primacy of destroying the enemy’s main force. Rather, the British strategist argued, controlling the lines of communications, both friendly and enemy, should be the main objective of naval warfare. Two ways to do that were through naval blockade or by capturing or sinking enemy warships and merchant ships. Corbett’s departure from the decisive battle principle prompted pushback from many of the Royal Navy’s more traditional admirals. Yet he enjoyed the backing of reform-minded First Sea Lord and Admiral of the Fleet Sir John “Jacky” Fisher.

In 1911 Corbett published Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. He wrote during a period of sweeping technological changes. Steam had already replaced wind and sail as the fleet’s primary motive power; steel hulls had replaced wooden ones; and naval guns were acquiring greater range, accuracy and hitting power. While there was no way Corbett could have foreseen certain technologies, he knew change was imminent and ongoing. That’s why he called his book Some Principles, rather than The Principles. His intent was to produce a living document to or from which future generations of naval thinkers could add or subtract.

Lessons

Determine the mutual relations of your army and navy in a plan of war. Only when this is done can one develop a plan for the fleet to best execute its assigned mission.

Offense and defense are not mutually exclusive. All war and every form of it must include contingencies for both.

The object of naval warfare is the control of communications. Naval operations in both world wars proved Corbett right.

The most pressing problem to solve is not how to increase the power of a fleet for attack, but how to defend it. Though Corbett wrote long before the advent of naval aviation, this remains the central difficulty of the aircraft carrier.