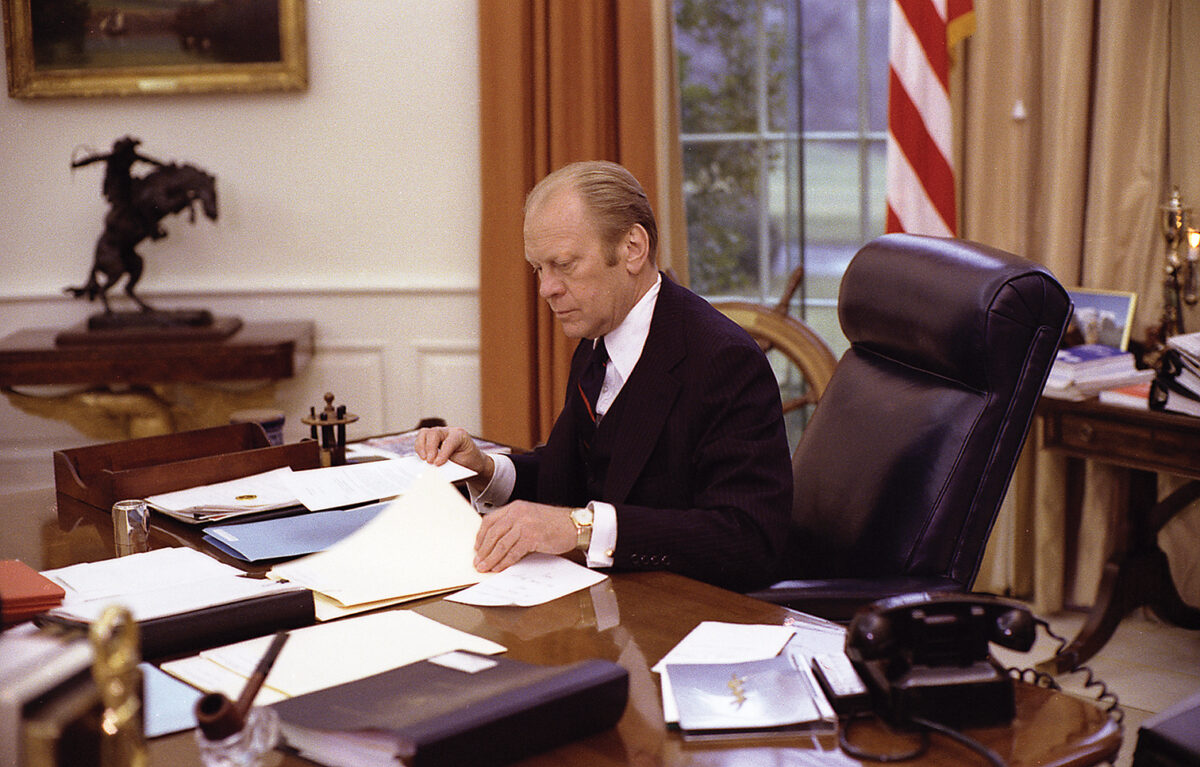

It’s about time we get to know Gerald Ford. We know his predecessor, Richard Nixon, who handed his vice president the presidency by resigning during the Watergate proceedings in 1974. We know the man who defeated him in the presidential election two years later, Jimmy Carter, and the man who in turn defeated Carter, Ronald Reagan, and went on to redefine the Republican Party.

Ford has been left to us as the bumbler from Michigan who stumbled into the Oval Office for a brief stint, pardoned his shamed former boss just to please the Republican Party, and then pardoned Vietnam War draft dodgers.

The historian and biographer Richard Norton Smith is trying to change that impression. He spent 10 years researching and studying the life and presidency of Gerald Ford, culling from numerous documents not previously available and conducting 170 personal interviews, including enough personal discussions with Ford himself that Ford asked him to deliver the eulogy at his funeral.

The conclusion of that effort is An Ordinary Man: The Surprising Life and Historic Presidency of Gerald R. Ford, the 832-page book published in 2023 that aims to recast the image of modern America’s accidental commander in chief from a punch line into a respectable Oval Office alumnus.

What would you say Gerald Ford is best known for?

There’s my generation: mention Gerald Ford and they’re as likely to think of Chevy Chase impersonating him on Saturday Night Live. It was a proxy. It wasn’t just physically clumsy. It was that Ford was intellectually deficient. That that was the implication. I don’t think he felt defensive about any of that. The one thing that really bothered him was the notion popular in some quarters that he was a party hack, that he was just a party guy. He knew that the first line of his historical obituary would revolve around his unelected status as vice president taking over as president after Richard Nixon resigned, and that the second line would include his pardon of Nixon for involvement in any covering up of the break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters in the Watergate Office Building in Washington, D.C. Then there was Ford’s conditional amnesty for Vietnam draft evaders, which happened about three weeks before.

How are these takes on Ford unfair?

Ford played football at a national level at the University of Michigan and yet finished in the top third of his class, a feat that he repeated at Yale Law School while simultaneously working full time as an athletic coach. And by the way, the clumsy reputation, you know, the man falling down the steps of Air Force One. It was a football injury. That literally haunted him. As for the pardon of Nixon, there are all sorts of criticisms that could be made. Probably, strategically, Ford had very few options other than to do what he did, but how he did it and when he did it, that’s certainly open to criticism. I’ve always believed that one reason contributing to Ford’s precipitous decline in the polls at the time was that even conditional amnesty for the draft evaders came as such a shock to his natural constituency.

What should Ford be known for that he may not be? Would you say he’s underrated as a president?

Certainly, in foreign policy, the Helsinki Accords, which were widely criticized from both ends of the political spectrum in 1975, are now seen very differently in light of everything that’s happened since. I think it’s a consensus that they are at the very least a major milestone on the road leading to the collapse of the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe and ultimately the Soviet Union itself.

The economy, if you look at the domestic front, economic deregulation, which is something we take for granted today. It’s hard to make Generation Y believe that there was a time, not so very long ago, in this country when the Federal government determined where planes could fly and what truckers could carry, and where you could get a home mortgage. The fact is that there has been lip service for years, particularly on the right, about deregulating the economy. For some people, that was part of a wide directive to undo or reverse the New Deal. Ford never bought into that. Ford was first of all a classic sort of Midwest right-of-center pragmatist who grew up in the shadow of the New Deal. He was part of that consensus generation that had the shared experience of the Great Depression and World War II.

The common perception may be that Ford lucked into his job. Did he deserve it? Was it something he aspired to?

He sure didn’t think of it that way. He never wanted to be president. He never wanted to be vice president. Well, no, I’ll take that back. He did want to be vice president, in 1960, years before he became one. Because he had proved to be such a vote getter early in his career, he was approached repeatedly about running for governor of Michigan or the Senate seat. He was offered an appointment to the Senate seat in 1966 by Governor George Romney. But he wasn’t interested in the Senate or being governor. He wanted to be Speaker of the House.

After he left the presidency, I think he felt a degree of guilt, particularly the burden that in some way his absences and all the additional demands placed on his wife, Betty, contributed in some ways to her problems. Now we know that much about alcoholism is genetic. Her father was an alcoholic. She had a brother who was also an alcoholic. Clearly there was evidence that she was vulnerable.

And she basically raised the kids, as he made it very clear. By the way, he said more than once in his later years that he thought when the history books were written, she, her impact, her contributions to the culture, would outweigh his own. I don’t think that’s necessarily accurate, but… Most people who become president want to be president to the exclusion of almost everything else, and that’s what makes him unique, because he never wanted to be president.

Kristie Miller, author of Ellen and Edith: Woodrow Wilson’s First Ladies, wrote of An Ordinary Man that “Rare is the history book that rewrites history. This is one.” How might you agree or disagree with that assessment?

I certainly didn’t say, OK, I’m going to sit down and write a work of revision. The thought never occurred to me. If people choose to reinterpret their take on history as a result, that’s up to them. I mean that people could draw their own conclusions. I’ve spent 40 years at this now, and I’ve always tried as hard as I could to avoid being a special pleader, and that means trying to present both sides, if not more than two sides, to most issues and the personalities that deal with them. I thought long and hard before doing this, and it wasn’t that I ever doubted, seriously, whether I could be objective, whatever that means—detached, critical. I remember something the great Pulitzer Prize–winning photographer David Kennerly said to me, that if you’re not critical, you’re not credible, and I believe that very, very much.

So this ordinary man of your title—underrated, unappreciated, and oft-forgotten—turns out to be a bit of an extraordinary president. How should we remember Gerald Ford?

I think his presidency is much less of a coda than it is a curtain raiser. It’s much more about what followed, including the Carter presidency and the Reagan presidency. One thing for which Ford gets no credit and the ’76 campaign at the height of the challenge from the right, from Ronald Reagan on the eve of the Texas primary, Ford sends Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to Africa because Ford has decided to do a 180-degree shift in U.S. policy toward White minority governments, beginning in Rhodesia. He is basically sending Kissinger to let them know that their days are numbered and that the United States henceforth is embracing the notion of Black majority rule. The implications of that are enormous. And, of course, on the day of the Texas primary, he got shut out by Ronald Reagan. It was a bad night, but it doesn’t matter because we did what was right and foreign policy is not going to be determined by the Republican primary schedule. That, in a nutshell, is what makes Gerald Ford relevant, and in many ways, the kind of president we say we want. He probably is, as we said earlier, more remembered for Chevy Chase’s pratfalls than for reversing American policy toward Black Africa. But that’s why people write books.

This interview appeared in the 2024 Spring issue of American History magazine.