History has long since established FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover abused his position, gathering defamatory information on elected officials, using his agents to intimidate and harass and beat suspects, and condoning flagrant abuses of civil rights. Hoover never forgot nor forgave anyone who made the FBI and himself look bad. He made inordinate efforts to destroy reputations and careers of men and women on his famous blacklist. But there was another facet to Hoover’s personal and professional character. As with the fictional John Riley Kane of “Citizen Kane,” Hoover had his own “Rosebud.”

Her name was Kate “Ma” Barker.

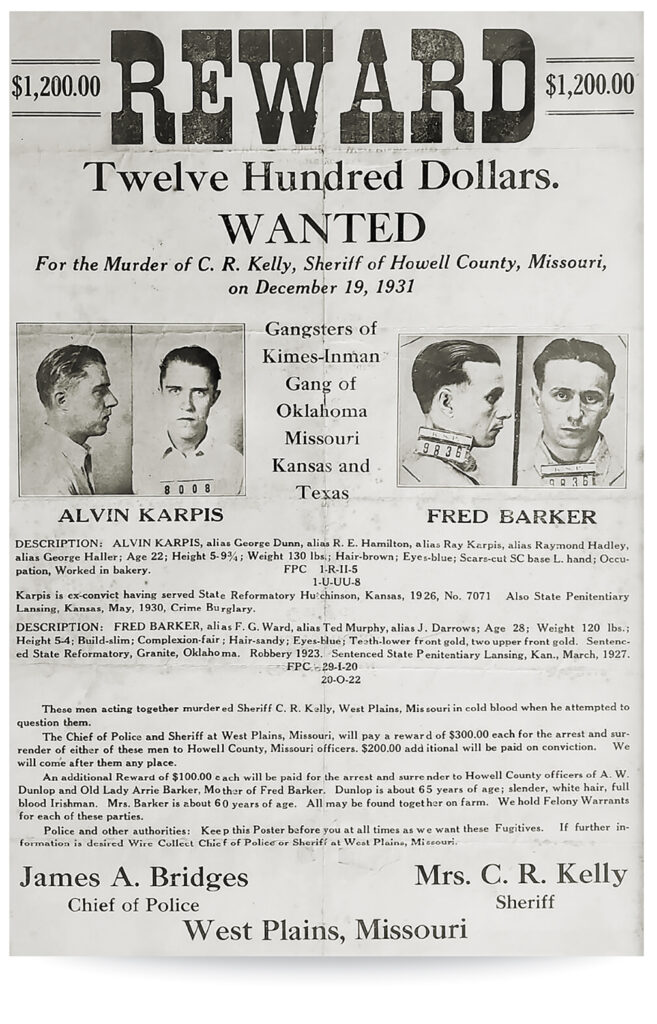

During the crime wave that swept the Midwest in the early 1930s, the names of John Dillinger, Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, Bonnie and Clyde, and George “Machine Gun” Kelly became as famous as Charles Lindbergh. The early years of the Great Depression spawned gangs of bank robbers, murderers, kidnappers and auto thieves the likes of which have not been seen since. Among the list of criminals of the era were a murderous gang of Missouri hillbillies that carried out several bank robberies and two audacious kidnappings before they were tracked down. They were the Barker-Karpis Gang.

According to Hoover, the head of the gang was an evil, scheming and notorious criminal genius named Kate Barker. In his 1938 book Persons in Hiding, Hoover wrote that Kate Barker was the “most vicious, dangerous, and resourceful criminal brain of the last decade.” This was in a decade that included John Dillinger, easily the most clever criminal of the age, and Lester J. Gillis, better known as “Baby Face” Nelson, who topped the list of true psychopathic killers. Yet Ma Barker had earned Hoover’s particular wrath. “In her sixty or so years,” Hoover continued, “this woman reared a spawn of Hell. Her sons looked to her for guidance, and obeyed her implicitly.”

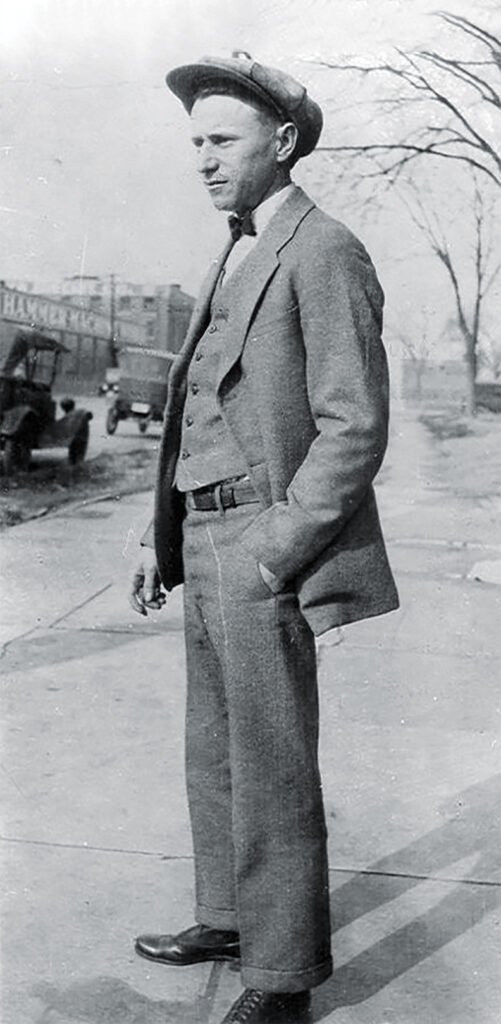

In truth there is no evidence that Ma Barker ever robbed so much as a filling station or participated in any crime. But Hoover, ever vengeful, labeled Ma Barker as the mastermind of the Barker-Karpis Gang. Not only was she never arrested or charged with any crime, she was completely unknown until after her death. She was plump and short, with black hair she liked to twist into rings and curls. She was a simple, nearly illiterate country woman who would have looked at home in a church knitting bee or pulling carrots from her backyard garden. Nothing more than a frumpy hillbilly woman, her only interests, other than her family, were to listen to the radio and assemble jigsaw puzzles. Hardly the image of a matriarchal head of an outlaw gang.

She was born Arizona “Ari” Donnie Clark in 1874 in rural Missouri. Her father John either died or left shortly after her birth. Her mother Emaline married Ruben Reynolds, and by 1885 the small family moved to Lawrence County. In 1892, when she was 18, Ari married George Barker, and they moved to Aurora. There they had three sons. Herman, born that same year, followed by Lloyd five years later, and Arthur, known as Doc, was born in 1899.

There is no census record of where they were living when Fred, the last son, was born in 1901, but by 1910 they were at Webb City in Jasper County. George supported his family with menial jobs. There is nothing to indicate he ever broke the law. The same could not be said of his four sons, all of whom became criminals. Physically, they were short and wiry, with black hair and sallow skin. As a sign of the times, neither Ari nor George made an effort to put their sons through school. All four were more or less illiterate. Fred, the youngest, was his mother’s favorite. She ruled the family with what was described as strong discipline. The eldest son, Herman, was remembered by local residents as being fascinated by Jesse James and the Youngers, both Missouri outlaws of the previous century.

Early on Sunday morning, March 7, 1915, Herman and another boy held up five men playing cards in the back of a grocery store in Webb City. Arrested the following day, Herman was released for lack of evidence. Ari packed up the family and moved to Tulsa, Okla., where she hoped her oldest son would have a fresh start. It did not happen. All four boys, even the 14-year old Fred joined a gang of boys and young men who committed small-time burglary and car theft in Missouri, Minnesota, and Oklahoma.

Hoover later called this gang a “school of crime, with Ma Barker being their teacher.” This is an example of how Hoover later inserted fictional vignettes of Ma Barker’s early rise in the criminal underworld.

Herman was in an out of jail several times over the next 12 years, and died in 1927 during a shootout with police in Wichita. Lloyd Barker, the next eldest, was arrested for robbing the U. S. Mail and sent to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in January 1922. Coincidentally, this was when Robert Stroud was raising his canaries there and was already known as the Birdman.

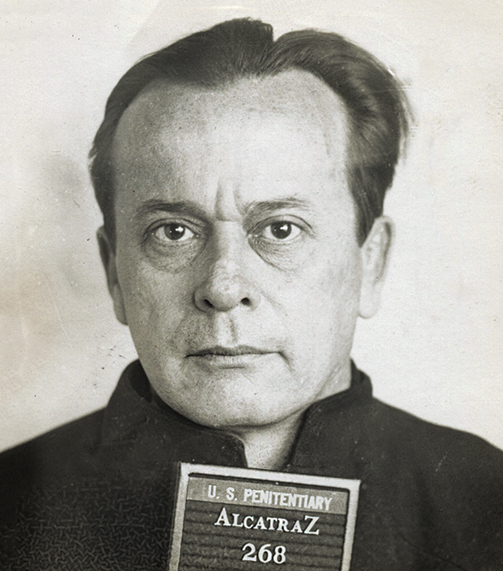

One month later, Arthur “Doc” Barker was sentenced to life for murdering a night watchman during a botched robbery at a Tulsa hospital. Doc had always shown a lack of sense and tended to be rash and violent despite his mother’s discipline. He was sentenced to life at the Oklahoma State Prison.

The family was left with young Fred, who was sent to live with a family friend, Herbert “Deafy” Farmer near Joplin. Farmer, whose own life as a criminal would span the next ten years, was a mentor to Fred until the young man was sent to a reformatory.

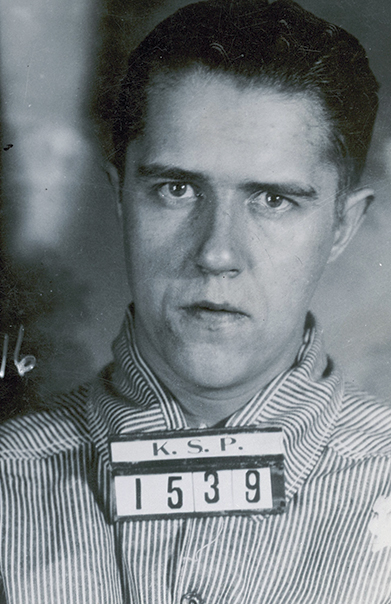

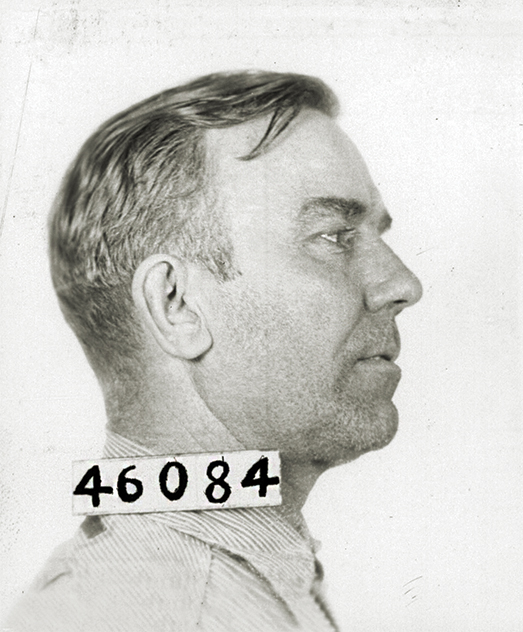

It was there that Fred met a young hood named Alvin “Ray” Karpis, the Canadian-born son of Lithuanian immigrants. Born in 1907, and a dead ringer for the horror film star Boris Karloff with glasses, Karpis was one of the Depression era’s most successful criminals, as well as the last one still alive in the 1970s. He would be the longest-serving inmate of Alcatraz.

Sometime in late 1928, George Barker either left in disgust with his criminal sons, or was thrown out by Ari, who had by now taken to calling herself Kate.

Karpis, after being released from the reformatory, went to find Fred and it was then he first met Kate Barker. She was living in a shack near some railroad tracks. “As I approached,” he said later, “she was wearing a pair of bib overalls over a man’s sweater.” He introduced himself and she invited him in. The shack had no electricity nor running water. A ramshackle outhouse was in the back yard. “There were flies everywhere.” But Ma Barker liked Karpis, and virtually adopted the young hoodlum, who eventually became as close as Fred.

Alvin Karpis, who later came to hate Hoover with a vehemence because of the FBI director’s self-proclaimed genius as the nation’s best investigator, said that Kate Barker was “gullible, easily led, simple, and generally law-abiding. The idea that she was the mastermind,” to use Hoover’s own words, was the most “ridiculous story in the annals of crime.”

Her only role was as a cover for the gang so they would look less conspicuous when they traveled. Convicted bank robber Harvey Bailey, who was well-acquainted with Kate Barker and her sons, said years later “Ma Barker couldn’t plan breakfast, let alone a major crime.” Rather than a criminal overlord, she was nothing more than an overindulgent mother who traveled with her sons and benefited from their ill-gotten gains.

So far the Barkers had not come to the attention of the Bureau of Investigation in Washington. It would not acquire the word “Federal” until 1935. The agents in Oklahoma and Missouri had never heard of the outlaw family, and certainly knew nothing of Ma Barker. Only the local city, county, and state police knew of them, even though Doc was in prison for a Federal offense.

Fred arrived from Joplin, and together he and Karpis began nighttime burglaries around Tulsa. They were both arrested. While Karpis was released, Fred later escaped. They took Ma and her current boyfriend, a drunk named Albert Dunlop, to southern Missouri. There they pulled their first bank robbery. Fred used the money to buy his mother a small farm. The boys did not remain. When a West Plains, Missouri police officer came to question them about a burglary, Karpis panicked and shot the lawman. Running just ahead of a posse, they took Ma and Albert to Herb Farmer’s place outside Joplin.

Farmer suggested to the boys they go to St. Paul, Minn., where the police were easily bribed. St. Paul, already considered the crime capital of the Midwest, was the home of a man who, while never indicted nor prosecuted, was one of the most notorious partners of crime in the state. Chief of Police Tom Brown took bribes and protected criminals while lining his pockets.

The Green Lantern Tavern, a favorite hangout for outlaws, was run by a portly man named Harry Sawyer. In December of 1931, Fred Barker and Alvin Karpis entered the big leagues of the Midwest’s criminal underworld. The Green Lantern often hosted Chicago gunmen and bank robbers, including Harvey Bailey and the soon to be infamous Machine Gun Kelly.

Where was Ma during all this? She was in a small home rented for her and Dunlop, where she kept house, listened to Amos ‘n’ Andy, and assembled puzzles. She was happy as long as she had her son, a roof over her head and something to do.

Sawyer took to the new arrivals and introduced them to more of his patrons. After one successful bank robbery, Karpis and Fred were sought for the crime. Tom Brown sidetracked the investigation while warning the boys. They suspected Dunlop as alerting the cops. They took the drunk out to the woods and shot him. This act alone disputes that Ma was a leader of the gang. She was lonely, and would not have allowed Dunlop to be killed. Fred, who was intimidated by his mother, rarely went against her wishes. But Dunlop was a threat.

In June 1932 , with Harvey Bailey, they robbed another bank in Fort Scott, Kan.. By autumn, they had enough money for the next step, getting Doc Barker out of prison. This was accomplished with the help of Tom Brown. A $200 dollar bribe to corrupt state Senator Preston Lester put Doc back on the street. Another bribe also released Volney Davis, another outlaw. There is some discrepancy on this matter, as many sources state Doc was paroled. But historians, going through FBI files, determined that Doc was released early due to bribery.

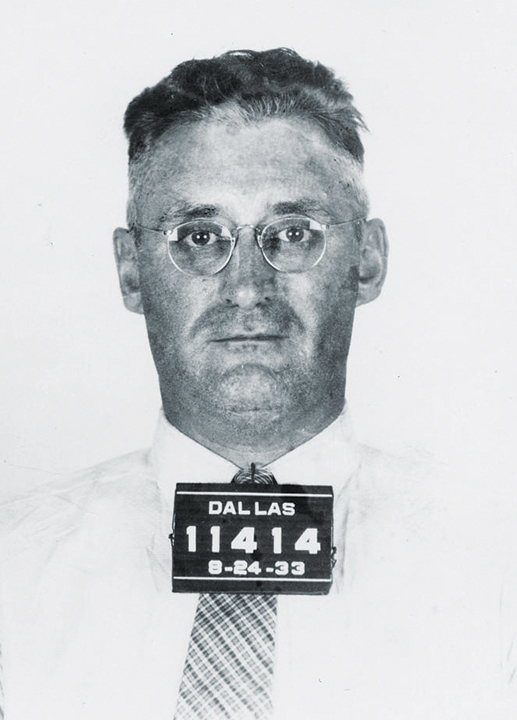

Now calling themselves the Barker-Karpis Gang, the four men joined up with George Ziegler, whose real name was Fred Goetz, and Brian Bolton, both from Chicago.

Goetz and Bolton, along with another man, Fred “Killer” Burke, were the then-unknown gunmen of the infamous St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in a Chicago garage in 1929.

Amazingly, Fred and Doc Barker, whose standing in the fugitive hierarchy was hardly worth mentioning, had been joined by the men who murdered seven of Chicago gang leader Bugs Moran’s men on the orders of Al Capone. Rarely in the underworld did the world of organized crime and the Depression-era hoodlums come together. Neither Goetz nor Bolton ever met Ma Barker, being content in her small and quiet apartment.

Sawyer, knowing Karpis wanted to find a less dangerous and more lucrative crime than armed robbery, told him about William Hamm, the scion of the old Hamm’s Brewery in St. Paul. He would be an easy target for kidnapping and ransom. Curiously, even though the June 1933 Hamm kidnapping yielded far more money than even John Dillinger had ever robbed, the Barkers were still unknown to the FBI. This was the crime that brought them into the hunt, since the passage of the Lindbergh Law in 1932 made interstate kidnapping a Federal crime.

Ma was still in St. Paul working on her jigsaw puzzles. She was aware of her sons’ crimes, but probably not the scale. As long as they came home with nice clothes and took her out for fun in the evenings, she was content. To be sure, Kate Barker was not a model of American motherhood.

The Hamm kidnapping yielded $100,000 in cash, which the gang laundered through their connections in St. Paul, Cleveland, and Chicago. Ma was shuffled from city to city as the gang kept ahead of the law. In August of 1933 Karpis was associated with Baby Face Nelson, and introduced him to other bank robbers. Karpis, always cautious, found Nelson to be too unstable and violent. Nelson, who often bragged about his connections in the criminal underworld, which included Dillinger, never mentioned even meeting the supposed matriarchal mastermind behind the Barker Gang. Furthermore, Nelson was very much a chauvinist, and would never have let a woman tell him what to do.

When the ransom money was distributed, the corrupt Tom Brown received $25,000 with the gang splitting the rest. But even in the 1930s, the money, with their profligate spending, did not last long. Fred sent Herb Farmer $2,500 to help pay his legal expenses when he was on trial for conspiracy.

Another kidnapping, that of businessman Edward Bremer on January 17, 1934, infuriated Hoover, who knew Bremer had connections to President Roosevelt. Hoover, who micromanaged the field agents to the point of verbally criticizing any typographical errors in their written reports, still knew nothing of Ma Barker. He rode the field officers mercilessly, to find out who had kidnapped Bremer. At last one of Doc Barker’s fingerprints was found on a cache of four gas cans left on a rural road where the gang had refueled their vehicles. Hoover’s men scoured the Midwest looking for Karpis, Fred, and Doc Barker, but no mention of Ma Barker turned up in their files or list of suspects.

It took months to launder the $200,000 in Bremer ransom money. The Departments of Justice and Treasury had posted the serial numbers to every bank in the country. Some of it was sent to Cuba, where it would spread to Mexico and South America. It was time to lay low. In September, Karpis, needing some time out of the country, visited Cuba with his girlfriend Dolores Delany. While there, he sent a letter to Ma in Chicago and invited her to come down. They spent a week fishing, boating, and relaxing in the beach house he had rented. But Cuba was under virtual martial law from the violence between the government and the revolt under Fulgencio Batista. Karpis returned to the states and began looking for another bank to rob.

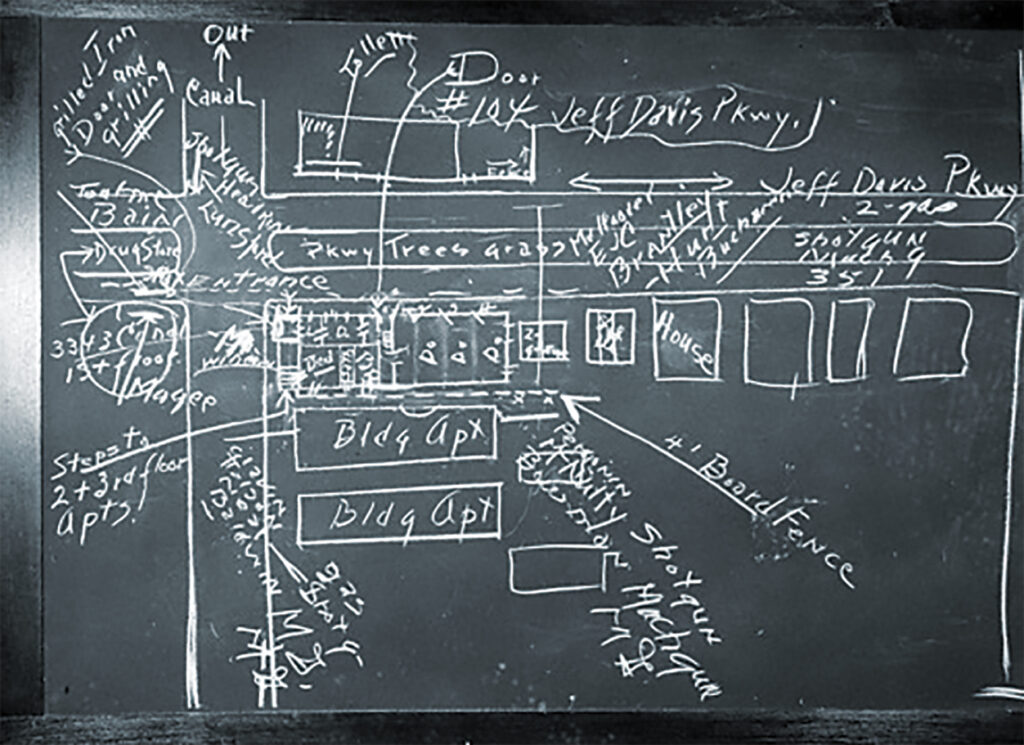

Then Doc, never the brightest of men, was arrested by Special Agent Earl Connally in early January. Among his personal effects was a map of central Florida, with a red ring circled around Lake Wier near Ocklawaha. That was where Fred and Ma were staying.

With Dillinger, Floyd, Nelson, and the Barrow Gang dead by this time, the Karpis and Barkers drew the full attention of Hoover’s agents. Earl Connally flew down to Florida and, with the help of Miami agents and local police, set up a cordon around the two-story lake house where Fred and Ma were staying. Karpis had visited the house only a few days before and felt it was too exposed. He advised them to find a better place. But Ma liked how quiet it was.

On the morning of January 16, Connally and his men, armed with tear gas grenades, rifles, shotguns and Thompson submachine guns, yelled for Fred to come out. Gunfire erupted from an upper window, then shifted to another. It was obvious only one person was shooting, as the shots never came from more than one window at a time. After firing tear gas and riddling the house with bullets, the agents waited, then called again. After three hours of more tear gas and fusillades of gunfire, the shooting ceased.

Connally, not willing to risk his men’s lives, sent the house’s caretaker, Will Woodbury, in to see if the Barkers were dead. Told by Connally that he would be okay, the frightened Woodbury went inside the house, still reeking of tear gas. A few minutes later he called out that both Fred and Ma were dead.

When agents finally summoned up the courage to enter the house, they found Ma and Fred dead, the latter riddled with bullets. Ma was lying nearby with a single bullet hole in her head. Not far from her left hand was a Thompson submachine gun. Almost immediately the story circulated that Ma had been found with a “smoking machine gun in her hand,” but the truth is more logical if not lurid. Kate Barker was right-handed. At ten pounds, the Thompson was a heavy weapon, almost impossible to handle when firing at full automatic. There was no way she could have used it;. The gun was Fred’s. Ma Barker was simply in the wrong place.

But Hoover, delighted to have the case closed, immediately told the press that she had been killed while fighting the agents. There is no doubt he wanted to spin the news away from the fact that his agents had murdered an old and unarmed woman. Thus the legend of the nefarious criminal mastermind Ma Barker was hatched and has persisted to this day.

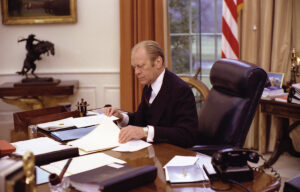

Even though the Barkers were active longer than any of the more famous Depression-era criminals, they were hardly known to the general public. Ma Barker’s notorious role was posthumous. Not being alive to defend herself, Hoover had full control of the outrageous legend. He never tired of talking about her. In fact, even as he directed the FBI through the Second World War, the McCarthy Era, the Cold war and several presidential administrations, he never stopped maligning the criminal fiend, Ma Barker.

Mark Carlson’s articles have appeared in numerous national magazines. He is currently working on the definitive account of the Lincoln Assassination.

This story appeared in the 2024 Winter issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.