Phil Kearny was born on a dark and stormy night in June 1815. He died on one, too. A major general in the Union Army, Kearny was out conducting his own reconnaissance, something he had done many times before. But in a driving thunderstorm on the evening of September 1, 1862, he and his escort rode into a Rebel ambush during the Battle of Ox Hill (Chantilly), a sharp encounter following the Confederate victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run. When Kearny cavalierly ignored an order to surrender and tried to ride away, a single bullet to the spine ended the life of a true fighting general.

Despite his untimely death, this fearless, feisty warrior had managed to live 47 action-packed years. A career military officer—though he never attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point—Kearny was destined to die in battle because of his reckless courage and determination always to lead from the front. Former General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, an old friend, called him “the bravest man I ever knew and the most perfect soldier.” Yet war was an environment he could have avoided altogether. Not only had Kearny lost his left arm in combat during the Mexican War—a disability that could have kept him out of the Civil War if he desired—he was one of the richest men in the nation in 1861.

FUTURE PROSPECTS, GREAT WEALTH

If his socially prominent parents had had their way, Philip Kearny Jr. would have never set foot on a battlefield, much less died on one. They wanted their son to be a lawyer, so he studied law at New York’s Columbia College (now Columbia University), graduated with honors and a law degree in 1833, enjoyed a European grand tour, and joined a prestigious New York law firm. Then fate extended him a golden handshake. When Kearny’s maternal grandfather died in 1836, he left the 21-year old attorney $1 million ($25 million today). Now financially independent, Kearny could pursue his childhood passion, a career in the U.S. Army.

Although a child of privilege, soldiering was clearly in Kearny’s genes. His uncle, Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny, was a hero of the War of 1812, considered one of the finest officers in the Regular Army. With Uncle Stephen’s backing, young Kearny was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 1st United States Regiment of Dragoons—the regiment in which his uncle had served. When he arrived at Jefferson Barracks, Mo., in June 1837, Colonel Kearny promptly sent the new shavetail to prove himself at Fort Leavenworth on the bleak Kansas frontier.

An expert horseman since childhood, Lieutenant Kearny thrived on the rigors of active field service. Among the troopers, he was known as a “hunky-dory shoulder strap” (Army slang for a good officer). Throughout his career, Kearny always made sure his men were well-fed, well-equipped, and well-cared for, even if he had to dip into his own deep pockets to do it.

Selected for special detached service in August 1839, Kearny set sail for France to attend the Royal School of Cavalry at Saumur. When he arrived, he was granted an audience and several dinners with King Louis Philippe I at Fontainebleau. To most officers, this would have been the assignment’s highlight. For Kearny, however, it was just a prelude for an adventure dearer to his soldier’s heart.

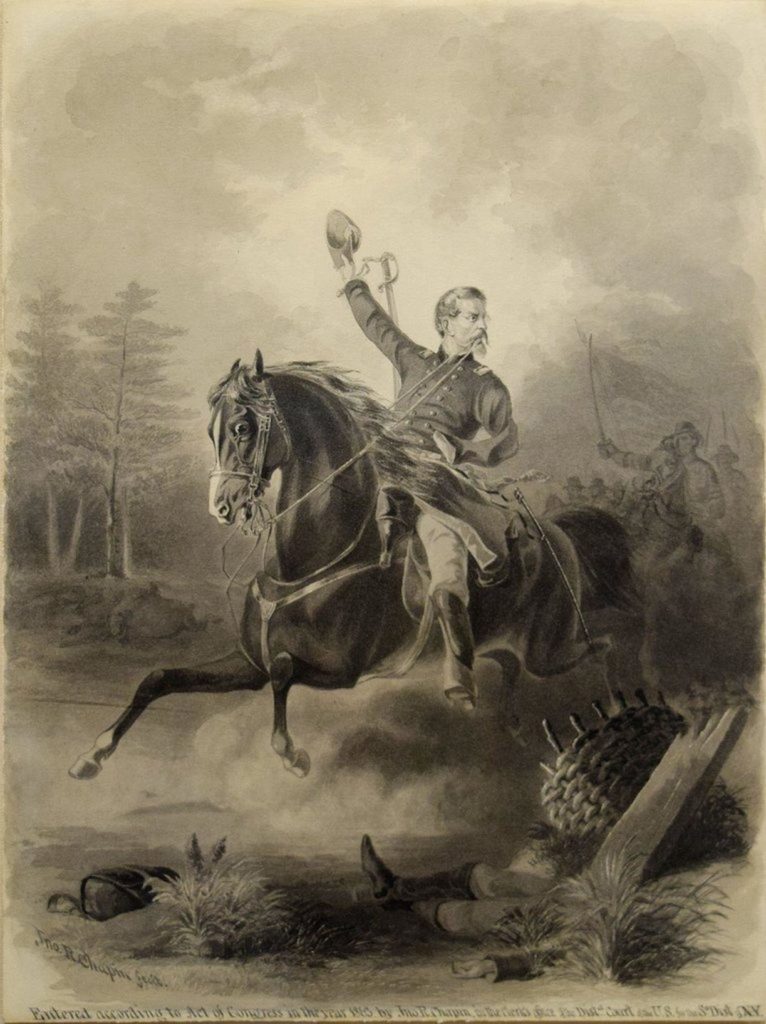

In addition to his military assignments, Kearny paid for gala dinners and dress balls for his admiring French hosts. The Duke d’Orleans, a frequent guest, invited him to join the 1st Chasseurs d’Afrique on an expedition against Arab insurgents in Algeria. Kearny accepted without receiving permission from Washington. In his first battle, Kearny rode with his sword in one hand, pistol in the other, and the reins in his teeth, earning him the nickname “Kearny the Magnificent”—the first of his many sobriquets.

Kearny’s first action made a lasting impression. To his lawyer, Courtland Parker, he wrote: “I have seen and tasted combat in Africa. It is an abomination….Yet, unlike others, I am thrilled by the charge….It brings me an indescribable pleasure.” The intensity of battle would always thrill him, but the agony of death always made him value the men he led.

AT WAR WITH LOVE

Phil Kearny’s private life was as tumultuous as his military career. A lion in combat, he fought his “affairs of the heart” with the same fierce abandon he showed on the battlefield.

An inheritance from his grandfather had made Kearny financially independent at an early age, allowing him to pursue his dream of a military career. (He inherited a second grand fortune, becoming one of the nation’s wealthiest men, when his father — a founder of the New York Stock Exchange — died in 1849.) While serving in Missouri in 1840, he met Kentucky-born Diana Bullitt, the military district commander’s sister-in-law. They became inseparable and everyone, including Diana, expected a proposal of marriage. Detached service in France, however, proved more attractive to Kearny and he left with barely a goodbye.

Kearny returned from France to Washington in 1841 and again encountered the still-smitten and still-single Diana Bullitt. They renewed their courtship, which this time led to a lavish wedding. Diana would settle comfortably into Washington society. Not so her temperamental husband, who rarely hesitated in making his displeasure known to his family and the Army.

In 1844, Kearny returned to the frontier and Fort Leavenworth, while his wife moved with their two children to his estate in New York. Kearny quickly became disenchanted out West and, anxious to repair his marriage, returned in October 1845 to resign from the Army. Diana now hoped for happiness and an attentive husband. Events in Texas would deny her both.

When a shooting war broke out along the Mexican border in April 1846, Kearny couldn’t resist the lure of action. He rushed to Washington to reinstate his commission. “I believe that it matters not to Phil whether I am in New York, return to Paducah, or live among the Hottentots,” Diana wrote to her sister. “He cares only for the Army and to participate in the war.”

Kearny did more than participate. Assigned to raise a troop of cavalry for his old regiment, the 1st Dragoons, Kearny recruited the finest men and bought the finest horses. But once again he got a staff assignment under Scott, this time in Mexico. “Honors are not won at headquarters,” he complained. “I would give my arm for a brevet.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Just a few weeks later, he got his wish. On August 20, 1847, after marching from Veracruz, Scott’s army arrived at the village of Churubusco, a suburb of Mexico City. Finally allowed to fight, Kearny led about 100 cavalrymen across a causeway to a gate to the city. Outnumbered, they nevertheless charged into the Mexican forces. Ignoring a call to retreat, Kearny, swinging his sword “chasseur style,” fought on with some of his men. About to be overwhelmed, Kearny ran back over the causeway and mounted another horse, ready to charge again. Then a piece of grapeshot tore into his left arm.

Although the wound cost Kearny the arm, he was promoted to brevet major and returned to the United States a bona fide hero with a reputation for reckless courage under fire.

Reunited with the family in December 1847, however, Kearny again chafed under the constraints of a growing family and peacetime Army routine. In August 1849, Diana—as arrogant and prideful as her famous husband—left New York for her family’s Kentucky home. Ostensibly, she had done so to give birth to their fifth child in her hometown, but the relationship evidently was beyond repair.

She never lived with her husband again, yet didn’t divorce him either. Her recalcitrance didn’t seem to bother Kearny, but serving in the Army with little chance for promotion injured his pride. In October 1851, he resigned his commission and embarked on a world tour. While in Paris, more than the city caught his fancy. He fell passionately in love with Agnes Maxwell, a socially prominent New Yorker—18 years his junior and already engaged to be married.

Their liaison created a sensation back home, so Kearny returned to New York in February 1854 to get a divorce. Diana refused. When Kearny suffered a near fatal riding accident, Agnes appeared to nurse her lover back to health. To avoid prying, disapproving New York society, they lived at Kearny’s baronial estate in New Jersey, “Bellegrove.” But when Agnes became pregnant in 1855, they again decamped for Paris where the more tolerant Second Empire society welcomed them and their new daughter, Susan. When they returned to New York in 1857, Kearny again demand a divorce from Diana.

Recommended for you

Fully aware of her husband’s adulterous life, Diana agreed—but only after Kearny threatened a custody battle over their son. He married Agnes in April 1858 and they returned to Paris, expecting to live the life of wealthy ex-patriots. Gathering war clouds at home inevitably changed their plans. When Kearny learned of the April 1861 firing on Fort Sumter, he exclaimed, “My God! They have all gone mad.”

Kearny loathed slavery and abolitionists in almost equal measure, but his devotion to the Union was unequivocal and the lure of action was too strong to resist. The couple closed up their Paris home, expecting to come back after Kearny fought in his fifth war. Neither of them ever returned.

POPULAR WITH HIS MEN

Kearny offered his services to his home state of New York but was refused a commission, probably because of his scandalous personal life. His “adopted” state, New Jersey, quickly stepped in and appointed him brigadier general of its first brigade of volunteers. He took command at Alexandria, Va., on August 4, 1861, and promptly moved the regiments to a better bivouac on the grounds of the Fairfax Seminary. From his headquarters in an elegant mansion, accommodations he paid for from his own pocket, Kearny enthusiastically began to turn clerks and farmers into soldiers.

Historian Bruce Catton has described Kearny as “all flame and color and ardor with a slim, twisted streak of genius in him.” The war would bring out all these characteristics and many more. In addition to personal courage, Kearny was a natural leader of men. He had a highly personalized command style and instinctively understood the importance of unit cohesion. Private Charles Hopkins of the 1st New Jersey Infantry remembered “his commands were religiously attended to as to food, clothing, proper medical aid, and best of equipment possible.”

In one instance, when Kearny learned that his troops were being fed spoiled rations, he confronted the quartermaster and raged: “You gave my men rotten pork and it was your place to see that it was good. Off with it, I say, and bring good meat or I’ll put you in here under guard, till you eat the whole six barrels of the damned stuff yourself…” The men got good pork and “One-Armed Phil” became a hero to his men.

After the Union defeat at First Bull Run, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan kept the Army of the Potomac drilling endlessly in its Northern Virginia camps. But Kearny, restless for action, sent his troops out to probe for the enemy. Encounters with Confederate pickets sometimes produced casualties, and when Lieutenant Harry B. Hinden of the 1st New York Cavalry was killed on March 9, 1862, Kearny sent a heartfelt letter of condolence to his mother. “With whatever fortitude you may alleviate your sorrow,” he wrote, “for you as a mother there can be no diminishing by his public glory, the anguish of a parent.”

Kearny understood a parent’s anguish firsthand. His youngest son, Archie, had died of typhoid fever the month before.

McClellan finally moved his army to the Virginia Peninsula in April 1862 for his long-delayed drive on the Confederate capital of Richmond. During the Peninsula Campaign, Kearny wrote a series of remarkable letters to his wife and attorney—full of praise for himself and his men and replete with low opinions of many subordinate officers and virulently critical his army commander. Many of the letters, in fact, sound remarkably similar to the vainglorious epistles McClellan wrote to his wife throughout his military career.

The May 5, 1862, Battle of Williamsburg was typical. It revealed Kearny to be a courageous fighting officer and a petty, jealous man. Now a division commander, he was ordered to support the troops of Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who were almost out of ammunition and in danger of being routed. After an arduous march through heavy mud, Kearny deployed his troops, directed their fire, and undoubtedly saved the Union flank from being turned.

His official report lavished praise on his officers and staff, from the brigade commanders “whose soldierly judgment was only equaled by their distinguished courage,” down to his volunteer aide, who “bore himself handsomely in this his first action.” Kearny even issued a supplemental report because he had failed to report “the distinguished acts of individuals not serving in my presence…who so ably sustained my efforts by their gallantry.”

But on May 15, Kearny vented his spleen in a letter to his lawyer, Courtland Parker, that resounded with insubordination. “General McClellan is the first Commander in history, who has either dared, or been so unprincipled as to ignore those under him,” he wrote, “who not only have fought a good fight, but even saved his army, himself, and his reputation.” He declared that McClellan “fears to admit the services of my Division, lest he, thereby, condemns himself for a want of Generalship, which gave rise to the dangerous crisis.”

Kearny’s division fought tenaciously throughout the Peninsula Campaign. His battlefield decisions were sound and his personal courage unquestioned. To the Rebels, he became known as “The One-Armed Devil.” In his report of the May 31-June 1 Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks), he proudly reminded McClellan that his troops “have again, within a very short period, paid the penalty of daring and success, by the marked and severe loss of near one thousand, three hundred men.”

‘NEVER BE FRIGHTENED’

Privately, Kearny continued to rail against his commander, partly because he believed McClellan slighted his exploits in official reports to Washington. A June 7 letter to his wife reeked of jealously verging on paranoia. “This is a strange army,” he wrote, “our battles come haphazard, and after every battle, it seems, as we all went to sleep, fearful, and stupid mismanagement on the part of McClellan, who is timid, ignorant of the nature of soldiers, and utterly incapable….In his last report, he with Cunning introduces me Lukewarmly in his Report, for at the late Battle, I was again sent for from a distance to turn the tide of battle.”

After the Battle of Malvern Hill on July 1, 1862, McClellan pulled his army back to Harrison’s Landing. Kearny found McClellan’s actions reprehensible. “I fear McClellan’s treason and mismanagement has thrown us in a great many fearful battles of much severity which he could have spared us,” he wrote to his wife on July 12. “But all of which he invited by his own bad management.”

Throughout the campaign, the tone of Kearny’s letters swung wildly from petulant complaint to genuine tenderness and concern. “You must be certain to go and see your school friend,” he wrote his wife from Harrison’s Landing. “I hope that you will make yourself as gay as you can, or else you will have a fearful hard time.” Kearny repeatedly reassured his wife not to worry about him and that he was safe and comfortable. “You ought to look once inside my tent,” he wrote, “and see my French camp bedstead, my rich furs; my braided cloak and shining velvet carpets; and a nice bottle of port at my side…”

Besides being an expert battlefield tactician, Kearny fancied himself a master of political policy, too. Claiming to understand the Southern mentality, he declared it time to deny the Rebels the use of slaves as a military resource. In a rambling letter to Parker, he opined: “As the blacks are a rural military force of the South, so should they indiscriminately be received, if not seized and sent off…I would use them to spare our whites needed with their colours—Needed to drill.” He also came to believe that McClellan‘s failure before Richmond meant “this war is no longer one of mild measures…Peace with the rebels on their own terms would only mean time to recommence.”

After nearly two months at Harrison’s Landing, Kearny’s division returned to Alexandria. From there, it joined Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia just in time for a second decisive battle on the plains of Manassas. On August 29, Pope found Stonewall Jackson’s Corps lined up behind an unfinished railroad cut above the Warrenton Turnpike, a position as good as a fort, and ordered an ill-advised attack.

Positioned on the far right of the Union line, Kearny’s division joined the fray late in the day and, in the battle’s most successful Union action, stormed out of a wood and almost turned the Confederate left flank. But without reinforcements, his decimated troops fell back. Watching the retreat of the 3rd Michigan, Kearny wept as the regiment went by, crying, “Oh what has become of my gallant old Third.” The next day, fresh Confederate troops under James Longstreet crashed into the Federal left and sent Pope’s regiments fleeing over Bull Run’s stone bridge toward the defenses of Washington.

Late that night, while his troops covered the Union retreat, Kearny sat down to write his after-action report. A young aide tried to steady the writing pad, but it quivered. When Kearny looked up, the young man confessed that the day’s events frightened him. Kearny gave him a sober, fatherly stare and said, “You must never be frightened of anything.”

The bombastic general’s ire had not abated when he wrote to Agnes: “It is tiresome to have one’s victory ignored…and to be ignored, though fighting hard and unsuccessfully; and exposing myself, as my nature unfortunately is, in other people’s defeats.”

When the defeated Pope learned that Jackson’s wing was on the move, looping around his flank to try to cut off his line of retreat, he ordered Kearny’s and Brig. Gen. Isaac Stevens’ divisions out of their muddy camps to intercept the Confederate column. They found Jackson on Little River Turnpike near a mansion called Chantilly. In the rain-lashed confusion, the two forces fought ferociously. Learning of a possible break in the Union lines, Kearny ventured forth, as he always had, to see for himself.

Inadvertently, Kearny wandered into the Confederate lines. He ignored an order to halt, probably from an officer of the 49th Georgia Infantry, and began galloping toward the safety of a nearby cornfield. As the soldiers fired at him, witnesses remembered him shouting, “They can’t hit a barn!” A bullet, purportedly fired by Sergeant John McCrimmon of Company B, entered the base of Kearny’s spine and lodged in his chest, killing him instantly. He fell from his horse into a muddy pool of rainwater. Colonel George Parker of the 21st Massachusetts, captured earlier in the day, identified Kearny’s body.

Over the years, there have been various versions of the events immediately following the general’s death. When Stonewall Jackson, who knew Kearny in Mexico, arrived, he purportedly said, “My God, boys, do you know who you have killed? You have shot the most gallant officer in the United States army.” Jackson removed his hat and bowed his head in tribute, as did a number of other Confederate soldiers around him. According to another account, Confederate Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill recognized the body by lantern-light after it was laid out on the porch of Jackson’s headquarters and proclaimed, “You’ve killed Phil Kearny[;] he deserved a better fate than to die in the mud.”

The next morning, Jackson’s battle dispatches arrived at Robert E. Lee’s headquarters. After reading the one announcing Kearny’s death, Lee immediately ordered Major Henry Taylor of his staff to arrange for passing Kearny’s body through the lines. Taylor had Kearny’s body and personal effects loaded aboard Jackson’s personal ambulance and taken to Fairfax Court House. After the war, Taylor recalled thinking “There is no place for exultation in the contemplation of the death of so gallant a man…I was conscious of a feeling of deep respect and great admiration for the brave soldier.”

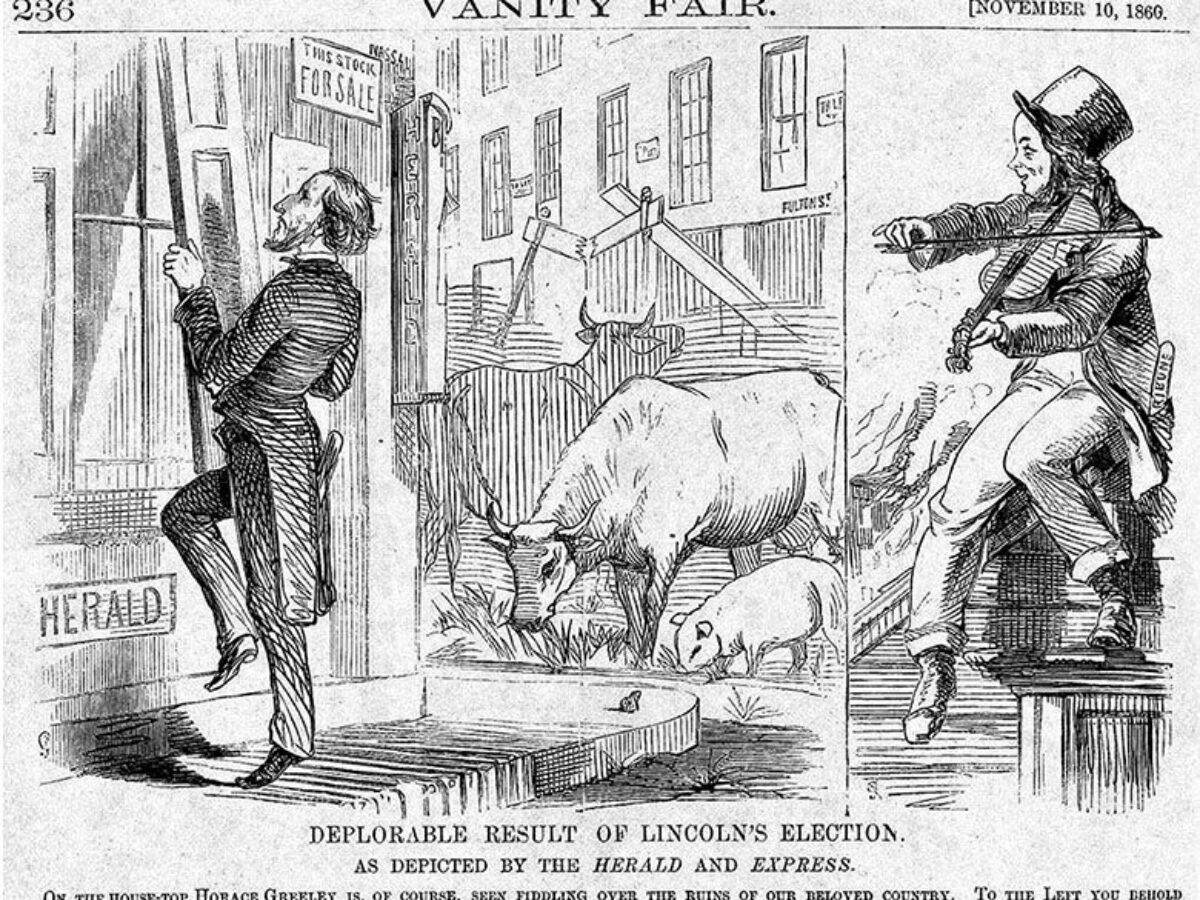

At St. Mary’s Church near Fairfax Station, the body was turned over to Federal pickets. Major General David Birney, commander of the Union troops at Chantilly after Stevens and Kearny were killed, selected troops and the color guard of the 57th Pennsylvania Infantry—part of “Kearny’s Own”—to accompany the body to Alexandria, Va. for autopsy and embalming. Word of Kearny’s death had already spread throughout the North, and the outpouring of admiration and grief was immediate and widespread. Harper’s Weekly plaintively asked, “Who can replace Phil Kearny?” The Tribune lamented “The death of Phil Kearny is a national loss.” In England, The Times of London noted: “At Chantilly fell one of the more gallant officers of the Federal Army, General Kearny.”

From Alexandria, a train carried Kearny’s body to Bellegrove, his palatial mansion in northern New Jersey. Thousands of people filed by the coffin during the four days it lay in state. On September 8, under a brilliant autumn sky, Kearny’s hearse rolled through Newark and Jersey City. His likeness adorned many windows along the route. Then it crossed the Passaic River by ferry and on to New York City. Thousands lined Broadway as Kearny’s flag draped coffin passed his childhood home at Number 3 and made its way to Trinity Church. There the coffin was placed in the massive Watt family crypt next to his maternal grandfather, James, whose death allowed Kearny to fulfill his passion to become a soldier.

Born to wealth, Kearny could have lived a safe and comfortable life. Instead, he chose service to his country, leaving behind a military record that few have matched. A.P. Hill had grieved that Kearny deserved a better fate than to die in the mud, but Kearny might have disagreed. If judged by his motto, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (“It is a sweet and fitting thing to die for one’s country”), Kearny likely died a happy man.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.