Historians frequently state that Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan suffered from a messianic complex and that he alone believed he had been called by God to save the Union. McClellan’s religious beliefs are often presented as a character flaw, personality disorder, or psychological malady. A quick look at the historiography of the general reveals that belief began with his contemporaries. In an 1894 article for Century Magazine, James B. Fry, formerly on McClellan’s staff, wrote, “The belief that he had been called to ‘save the country’ had seized upon him….[T]he strong religious element of his character served to fasten the conviction and blind him to the obligations and influences which governed him at other times. Under the power of this hallucination he was insensible of his own weaknesses and errors.”

Modern historians have agreed with Fry’s assessment. In his 1952 book, Lincoln and His Generals, T. Harry Williams bluntly stated that McClellan “developed a Messianic complex.” James B. McPherson echoed that in his 1988 Pulitzer Prize–winning Battle Cry of Freedom, claiming that “McClellan’s letters to his wife revealed the beginnings of a messiah complex.”

That same year, in his biography, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, Stephen W. Sears offered: “Taking the role of God’s chosen instrument might be dismissed as nothing more than a harmless conceit but for the effects it produced on his generalship. It was at once the prop for his insecurity and the shield for his convictions. With Calvinistic fatalism he believed his path to be the chosen path, anyone who raised criticisms or objections…was at best ignorant and misguided and at worst a traitor.”

Did the commander use God to escape responsibility, rationalize, or offer excuses for failure? Was he unique in that regard? To the secular mind of the 21st century, professing to be God’s chosen instrument appears to be conceited behavior or a self-righteous delusion. These judgments may seem plausible when viewed through the vacuum of modern skepticism; however, as we shall see, for citizens of the mid-19th century the notion of consigning oneself over to God’s will was a common principle in all Christian denominations. The following examples will prove Little Mac was not alone in his thoughts.

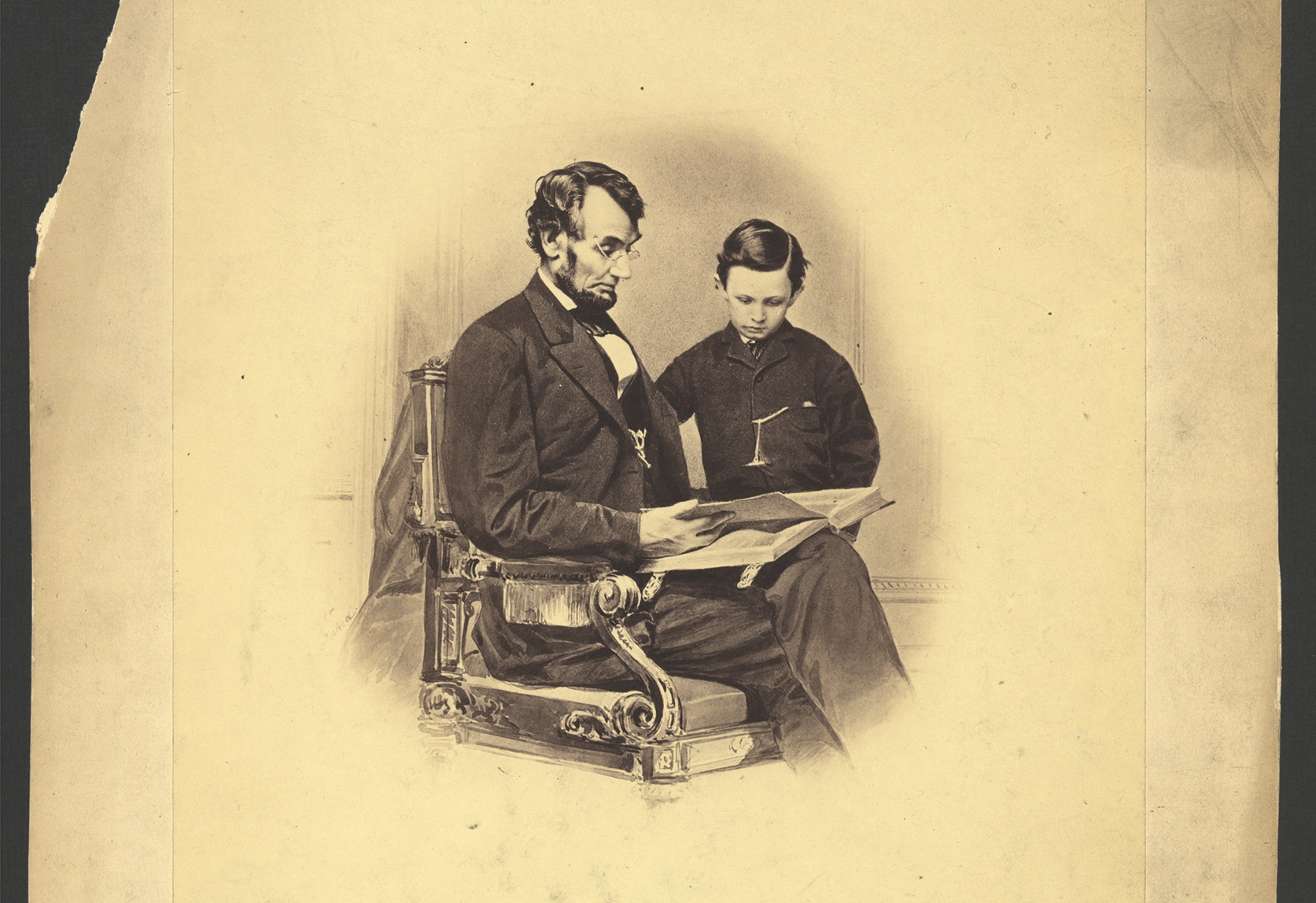

On September 2, 1862, shortly after the disastrous defeat of Union Maj. Gen. John Pope at Second Bull Run, President Abraham Lincoln found himself musing about God’s purpose regarding the present crisis facing the United States. In a short essay titled “Meditation on the Divine Will” he wrote for his personal use, Lincoln sought to explain General Pope’s failure as an act of God.

“The will of God prevails,” began Lincoln. “In great contest each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God.” Here, Lincoln grappled with the age-old paradox of both combatants claiming to have God on their side. As the president observed, however, “Both may be, and one must be wrong. God cannot be for and against the same thing at the same time.” One side must be right, one side must be wrong, but which? The answer was unfathomable: “In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party.” Unfathomable or not, there had to be some plan on God’s part because “the human instrumentalities, working as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect his purpose.” This statement bespeaks of predestination: human beings, and their actions, are reduced to instruments of God’s will.

“I am almost ready to say this is probably true, that God wills this contest,” continued Lincoln, “and wills that it shall not end yet.” The war would continue because God had willed there be a contest, and as far as Lincoln could tell the outcome was still in the hand of God. The Union could win or lose; it was up to God. He ended his musings with the simple observation that God “could give the final victory to either side any day.” In this secret meditation, Lincoln sought to find some divine meaning to the recent unfortunate turn of events. The best the President could deduce was that he was one instrument of many fulfilling God’s purpose, and whatever the outcome, it was in the hands of God.

Although he never formally joined any church, Lincoln grew up in a highly religious Baptist family. The president attended Protestant church services with his wife and children. Lincoln’s religious beliefs, such as they were, must be viewed within the context of his religious experience and time. “Mainstream Protestant morality was dominated by various forms and nuances of predestination doctrine,” observed historian Thomas J. Rowland, “particularly as it related to man’s need to submit to the will of God.”

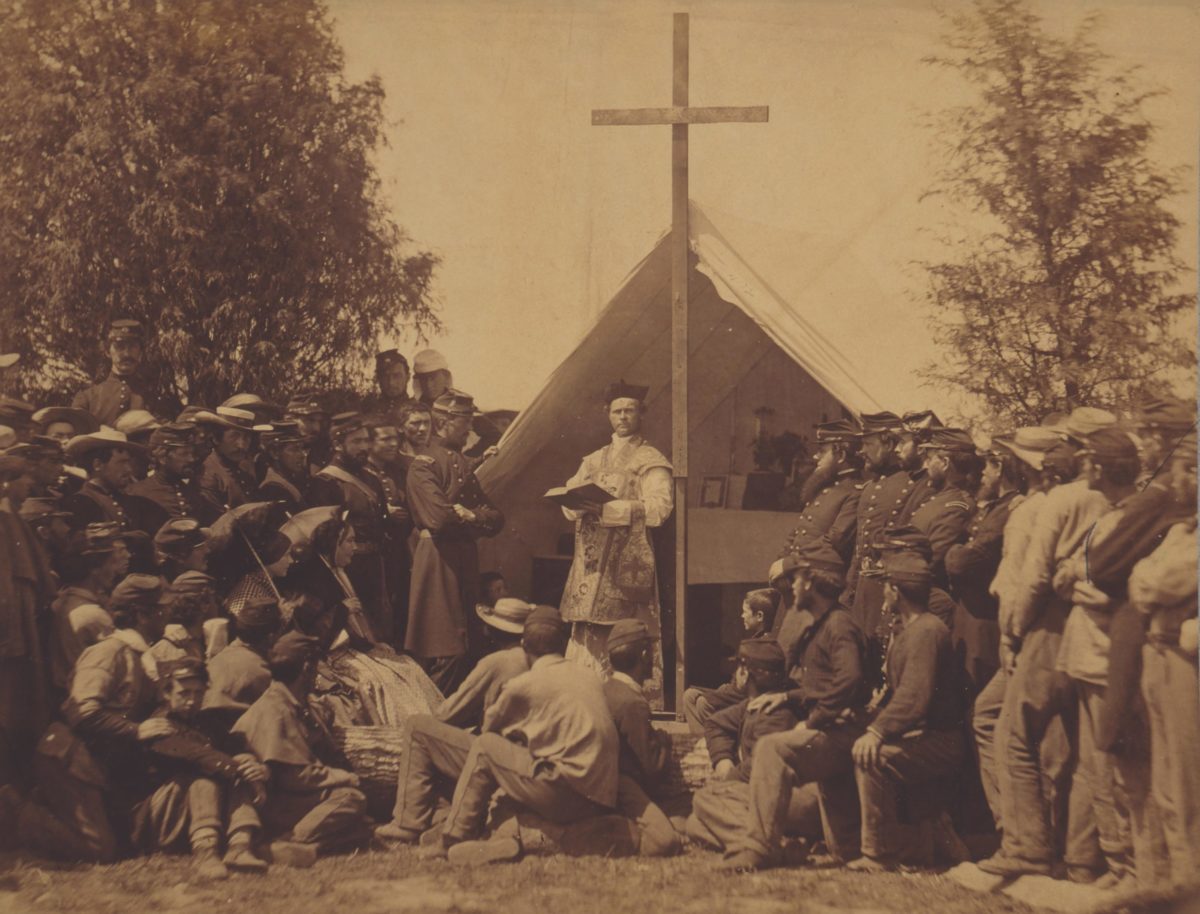

Lincoln’s experience was not unique. Religious belief permeated the rank and file of both armies from the lowly private to the commanding general. Many unit commanders led their men in prayer before taking them into battle and soldiers often referred to their first combat experience as their baptism of fire. It was not unusual to march into battle with Bibles, rosaries, or some other religious artifact tucked in their pockets. Major Frederick L. Hitchcock with the 132nd Pennsylvania, during his first taste of combat at Antietam’s Bloody Lane, no doubt expressed the common feeling of many soldiers when he wrote, “How does one feel under such conditions….I said to myself, ‘this is the duty I undertook to perform for my country, and now I’ll do it, and leave the results with God.’”

Confederate General Robert E. Lee was formally confirmed in the Episcopal Church. Lee was renowned for his piety, including his total commitment to Divine Providence: the governance by which God controls, among other things, the activities of nations and human destiny. The Army of Northern Virginia commander believed that God intervened in the affairs of men and that God’s will was a more determining factor in success or failure than men’s abilities. In a prewar letter to his disappointed wife, during a time of slow promotion, Lee wrote, “We are all in the hands of a kind God, who will do for us what is best.”

Lee carried those beliefs into the war, often when his tactics failed to defeat an opponent, it was because “God ordered otherwise.” Indeed, as Thomas L. Connelly has noted, “Lee’s belief in God’s intervention was an important part of his wartime personality….He saw the Southern army as controlled by a divine hand, and believed that battles were determined by God.” When his plans failed in western Virginia in 1861, Lee declared, “I had taken every precaution to insure success…but the Ruler of the Universe willed otherwise.” To explain the awful Confederate casualties inflicted at Malvern Hill during the Seven Days, Lee is on the record as offering the rationalization, “God knows what is best for us.”

Lee often interpreted defeat as punishment by God. If one were inclined to use religious belief as the basis for a psychological malady, one could arguably use the forgoing to make the claim that Robert E. Lee suffered a persecution complex at the hands of God. But just the opposite is true. Lee was often portrayed in the 19th century as the personification of the Christian Gentleman.

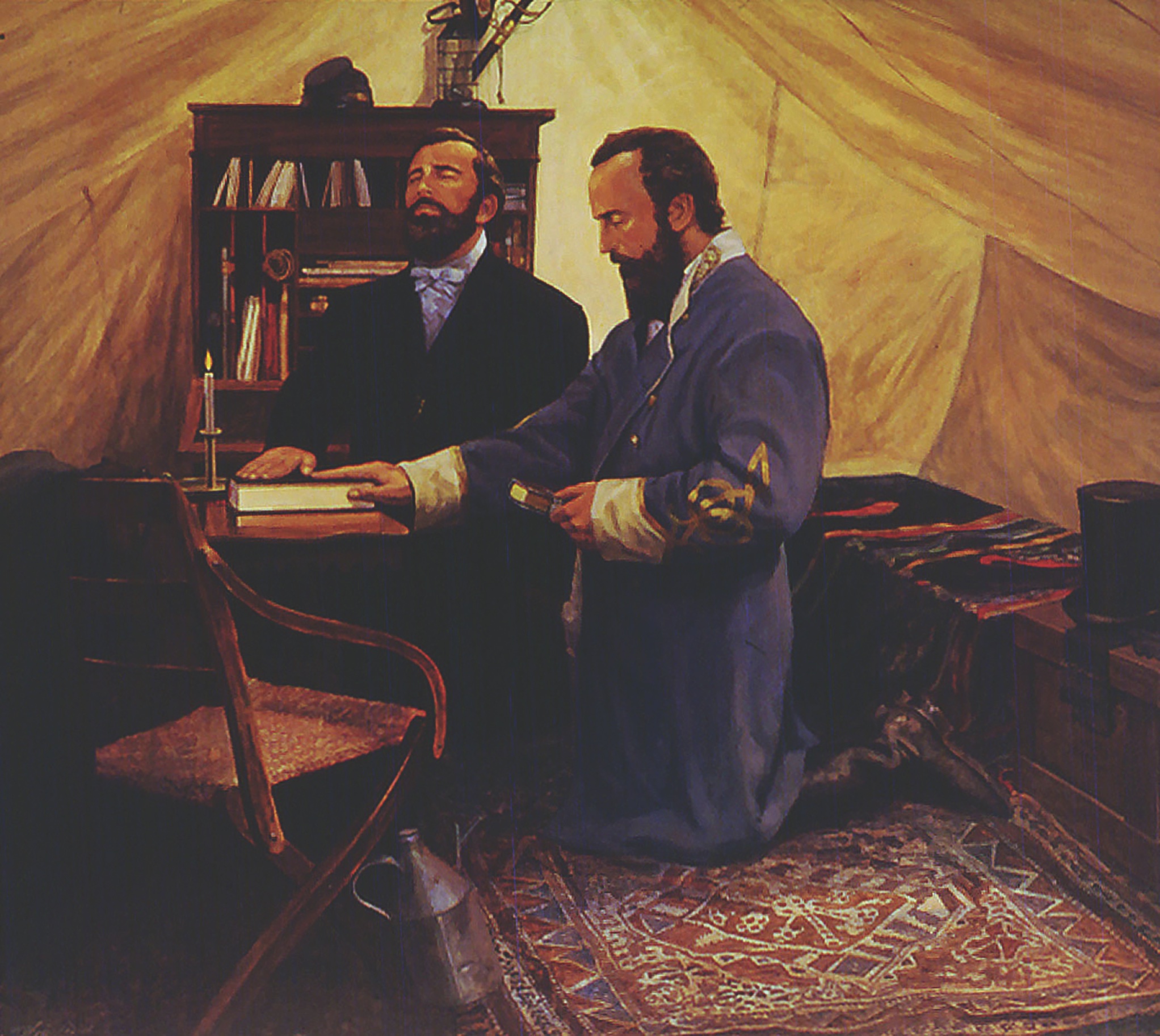

And then there is the war’s most famous religious general, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Henry Kyd Douglas, one of his greatest advocates, described him as a “quiet Christian gentleman,” but added, “he was a Presbyterian but might just as easily have been a Methodist or an Episcopalian or, perchance, a Catholic.” According to Douglas Southall Freeman, Jackson “lives by the New Testament and fights by the Old.” Whatever his denomination or testament he followed; Jackson continually unnerved his command with his militant spirituality. He has been described as “fanatical” in his faith. As Stephen W. Sears noted, “His dispatches invariably credited an ever-kind providence.” It was not uncommon for Jackson to inform Lee that success had been achieved “Through God’s blessing.”

During the 1862 Maryland Campaign, Jackson wrote his commander of the Confederate victory at Harpers Ferry and began the dispatch, “Yesterday God crowned our army with another brilliant success.” By assigning his fate to God’s hands, Jackson acted fearlessly on the battlefield with an unnerving sense of fate which undoubtedly contributed to his premature death less than halfway through the war. Indeed, a contemporary newspaper correspondent described “Stonewall” as “a Presbyterian who carries the doctrine of predestination to the borders of positive fatalism.”

Jackson was convinced that pious soldiers would always prevail and that God favored his every move. Tom Rowland has observed, “For Jackson, war was a purifying process which cleansed the soul of iniquity and transformed the baseness of human nature.” If one were looking for a candidate for a messianic complex one could easily stop with “Stonewall” Jackson. Yet, as Rowland has further observed, “Jackson, for all his eccentricities, has more frequently been hailed a genius than a self-styled messiah.”

This brings us to the Civil War’s most misunderstood religious general, George B. McClellan. On the same day that Lincoln mused about God’s will, September 2, he and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck visited McClellan at his home. After the visit, McClellan wrote to his wife, Mary Ellen. “I was surprised this morning…by a visit from the Presdt and Halleck,” he wrote, “in which the former expressed the opinion that the troubles now impending could be overcome better by me than anyone else.”

He next simply informed his wife, “Pope is ordered to fall back upon Washn & as he reenters everything is to come under my command again.” McClellan admitted to Mary Ellen that he considered it, “A terrible and thankless task…I will do my best with God’s blessing to perform it. God knows that I need his help.” He then asked his wife for her prayers, “Pray that God will help me in the great task now imposed upon me.” McClellan then stated he assumed the task “reluctantly,” and “with a full knowledge of all its difficulties & of the immensity of the responsibility.” He confessed, “I only consent to take it for my country’s sake & with the humble hope that God has called me to it, how I pray that he may support me!” He ended this short missive to Mary Ellen with the assuring words, “Don’t be worried, my conscience is clear & I can trust in God.”

It was a very different age.

We gaze at the images of Civil War participants, read their written records, and walk in their battlefield footsteps, all factors that can make us feel as if they are familiar and we “know” them. But their lives, and scientific knowledge, were vastly different from ours. They were people of another age. Gott- lieb Daimler and Carl Benz were still 23 years away from producing the first successful gasoline engines. The idea of generating artificial light by passing an electric current through a wire filament inside a glass sphere was still years away. People, even the wealthiest, lit their homes with candles, fires, and oil lamps. In the mid-1800s, there were reputable scientists who still believed in the theory of Spontaneous Generation—the idea that certain forms of life, such as flies, worms, and mice, developed directly from non-living matter. Charles Darwin’s controversial ideas on evolution as set forth in his Origin of the Species had been in print for only three years when Abraham Lincoln penned his September 2, 1862, meditations. The first complete dinosaur skeleton had only been unearthed four years previous and another six years would pass before it was put on public display. The concept that creatures other than human beings had once dominated the earth was still some years on the horizon. Neptune, the eighth planet in the solar system, had been discovered only 16 years earlier. Concepts of time, space, and the geological history of the Earth were still very much defined by the book of Genesis. In the mid-1860s, the natural world was still mysterious enough to suggest a supernatural power that governed the course of events; religious belief and prayer still occupied a very dominant and influential part of day-to-day life. In this context, there was nothing odd or peculiar about generals and presidents regarding the will of God. —S.S.

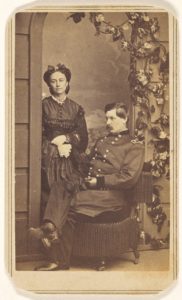

Some modern historians see in this letter a character defect of false humility, others use it to represent a far more serious psychological malady. But the letter must be considered within the context of his marriage and the religious beliefs prevalent in his time. If the correspondence were with someone other than his wife, perhaps the charge of false humility might stick. McClellan’s wife, however, was the one person he could honestly bare his soul to, and he did repeatedly. He had absolutely nothing to gain by putting on a false front for his wife’s sake. McClellan and his wife participated in a marriage of mutual support. In this context, there is certainly nothing unusual in a young man complaining to his wife of an immense task placed before him.

What is unusual, to the contemporary reader, is the invocation of God. It has been used by some of McClellan’s modern critics to demonstrate proof of a messianic complex on the part of the Young Napoleon. It is not uncommon to find the modern authors, such as Joseph T. Glatthaar in his 1994 Partners in Command, The Relationships Between Leaders in the Civil War, using such correspondence as confirmation that McClellan set himself up as a “Christ-like figure…a chosen instrument, fulfilling God’s will.” Charges of psychological disorders without clinical evidence lead one down a slippery slope to begin with, but the charge of the messianic complex is perhaps the most slippery of all the anti-McClellan slopes. As we have seen, the list of other 19th-century personalities that considered themselves instruments of God’s will certainly argues against singling out Little Mac for this alleged malady.

He often wrote messages meant for her eyes only that contained religious references and overtones. (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

In addition to the religious influences of his time, McClellan was greatly influenced by his wife’s Presbyterian religious beliefs. By his own admission, George McClellan never professed any adherence to a specific Christian denomination until he met Mary Ellen Marcy. By the time they were married on May 22, 1860, McClellan had undergone an evangelical rebirth that fundamentally changed his outlook on life. He openly embraced the tenets of Calvinism and mainstream Presbyterianism.

McClellan—along with many other Presbyterians of his day, Stonewall included—openly embraced the dogma of predestination, a doctrine which states that God determines the eternal destiny of humanity. In this context, McClellan’s letter is perfectly understandable; “I will do my best with God’s blessing….God knows that I need his help….I only consent to take it [command]…with the humble hope that God has called me to it….I can trust in God.” It is only natural for the modern secular mind to perceive such expressions as false humility. For the modern historian, the label of “messianic complex” is an easy way to explain the motivation behind a historical figure that believed he was God’s chosen instrument to save the Union. Such simple heart-felt religious belief, it seems, has become too naive a concept for the 21st century mind.

McClellan’s religious convictions were no more abnormal than those of his contemporaries who embraced God’s Will. Consider these two statements. “It is probable that we shall have a severe engagement today…I feel as reasonably confidant of success as anyone well can who trusts in a higher power & does not know what the decision will be,” McClellan wrote to his wife on September 14, 1862. On July 2, 1863, Robert E. Lee told a foreign observer, “I do everything in my power to make my plans as perfect as possible…the rest must be done by my generals and their troops, trusting to Providence for the victory.” Stonewall Jackson believed all victories came through God’s blessing. Lincoln believed that humans were simply instruments playing out their parts in some grand scheme of God’s. Yet, because McClellan also believed he was God’s instrument, he is singled out for being the victim of some debilitating religious psychological malady. What is seen as virtue in others becomes vice for Little Mac. Such is the nature of the historical double standard by which George B. McClellan is judged.

Steven R. Stotelmyer, who writes from Sharpsburg, Md., is the author of Too Useful To Sacrifice, Reconsidering George B. McClellan’s Generalship in the Maryland Campaign. He is a certified tour guide for the Antietam and South Mountain battlefields.