On February 7, 1825, Samuel Morse’s wife, Lucretia, died suddenly, at the age of 25, while Morse was working in Washington, D.C. By the time he was notified by letter and had returned home to New Haven, Conn., she had already been buried.

Perhaps motivated by his regret, in the early 1830s, Morse began perfecting his version of an electric telegraph and, with the help of researchers Leonard Gale and Alfred Vail, produced a single-circuit version. By pushing a key, the operator sent an electric signal across a wire to a receiver at the other end. Soon thereafter, Morse and Vail developed the code that would translate the pulses and silences to language.

On May 24, 1844, Morse sent his first telegraph message, from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore, Md.: “What hath God wrought!”

Indeed. Its invention forever changed communication, and with it, transformed everything. A message, a military order, a money transfer, a piece of news, that once took weeks to deliver by horse and carriage, could now be exchanged almost instantly.

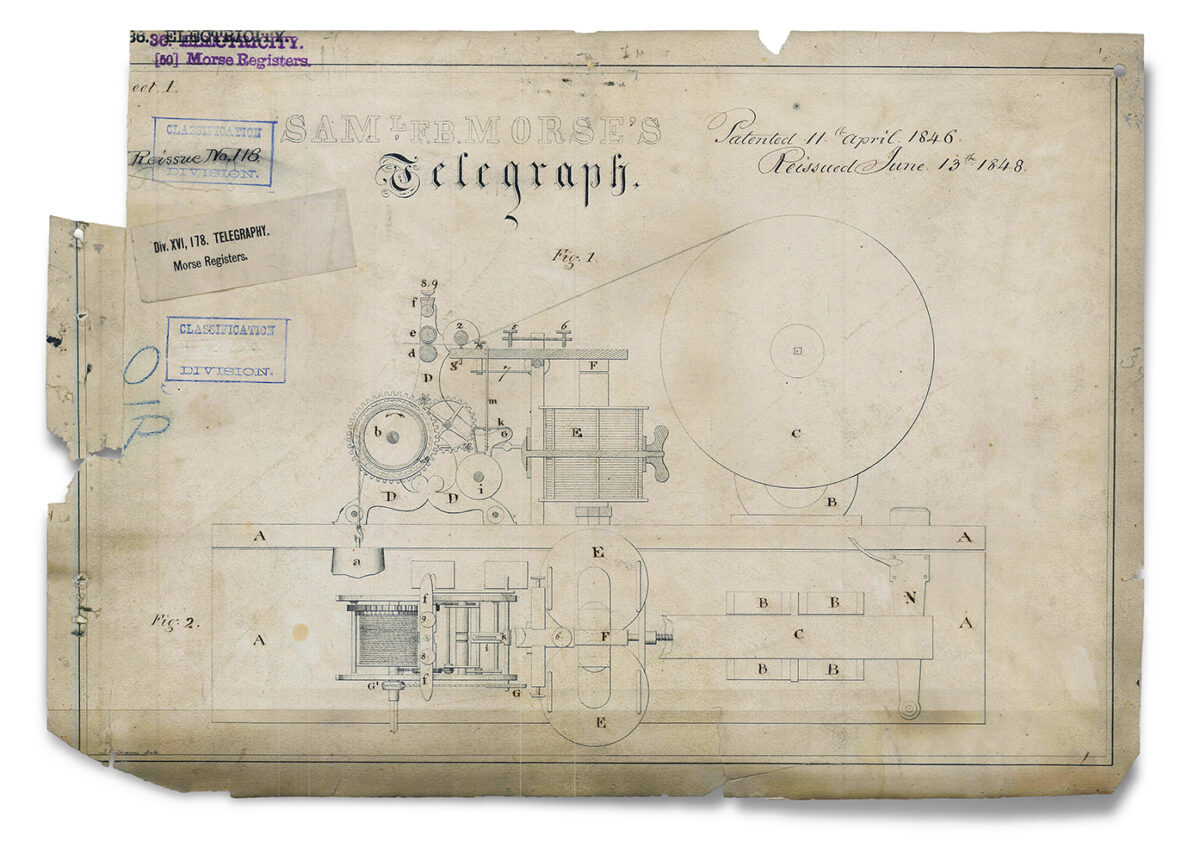

On April 11, 1846, the patent shown here specified a combination of devices to move and mark a paper roll to record the incoming message; and, more importantly, the use of a magnet in the telegraph receiver to amplify the current, enabling the telegraph to receive messages over longer lines—a long-distance call.

By 1866, the first permanent telegraph cable had been successfully laid across the Atlantic Ocean.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.