Alfred Vail came up with dots and dashes, but Patent Office gave credit to Samuel Morse, the better known inventor

In 1887, 18 years after his father’s death, Stephen Vail took up metaphorical arms to claim Alfred Vail’s place as a key figure in communications history. Starting a war of words that would last decades and end with a declaration carved into stone, the younger Vail bombarded newspaper editors with letters. Alfred Vail’s son insisted that his dad had invented the dot-and-dash system used in telegraphy and known to all, and most gallingly to the younger man, as “Morse” code.

Before telegraphy, the United States had been more a collection of outposts than a nation—when a treaty ended the War of 1812, word from peace talks in Europe between Britain and the United States took so long to creep across the Atlantic that two weeks after the signatures on the peace treaty had dried British and American troops were fighting the Battle of New Orleans. Until telegraphy arrived for good in 1844, information traveled no faster than horses could gallop, trains could roll, or ships could sail. News from Boston reached San Francisco and vice versa by traveling aboard vessels that had to round South America’s southern tip. Only dreamers spoke of rails crossing North America or a canal traversing the Isthmus of Panama.

Then a couple of fellows named Alfred Vail and Samuel F.B. Morse got into the act.

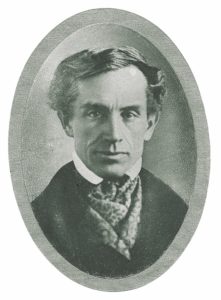

Since the 18th century, scientific savants had been talking about electricity’s potential to revolutionize communications. The theoretical means had a name—“telegraph”—compounded of the Greek for “to write” and “at a distance”—but no practicable form. In October 1832, one of those visionaries, Samuel F.B. Morse, was sailing to New York from France. Six feet tall, Morse, 41, was a successful artist—he taught art at newly opened New York University—and a stubborn extrovert with an interest n invention. At dinner one evening, shipboard table talk turned to the topic of electromagnetic communication. Inspired, Morse pictured wires somehow carrying messages. His concept was vague, but, as he wrote later, he saw no reason “why intelligence may not be transmitted instantaneously by electricity.” Once back in Manhattan, Morse began to tinker with his notion. Impelled by loathing for immigrants, he briefly distracted himself with a failed 1836 run for mayor of New York on a nativist ticket.

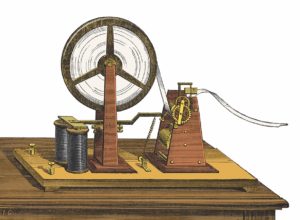

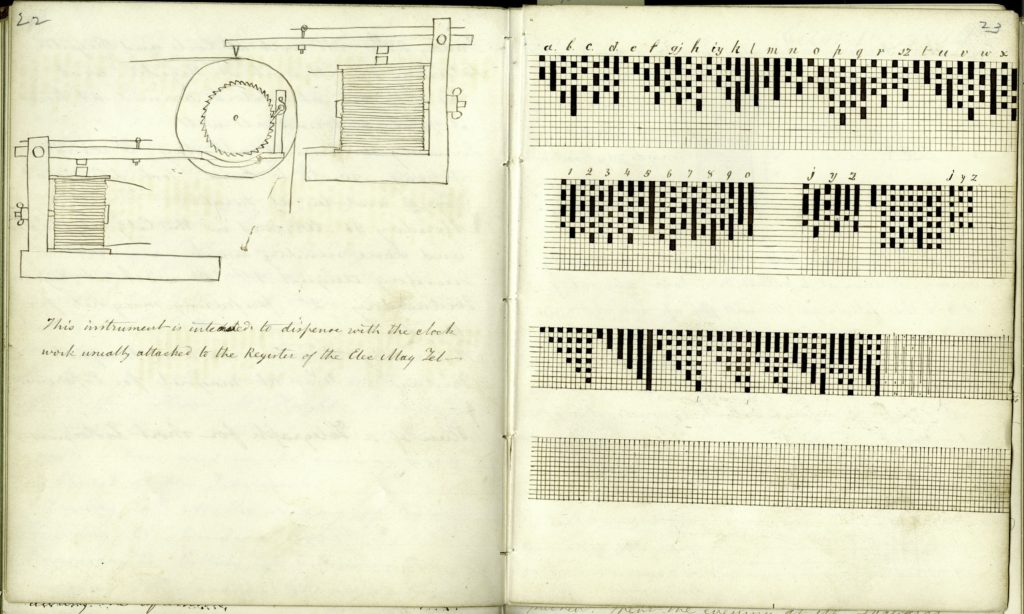

But Morse never gave up on telegraphy, envisioning a system he called the Electro-Magnetic Telegraph. As a test of his premise, Morse strung a room at NYU with 1,700 feet of bare 18-gauge copper wire. The wire linked a transmitter and a receiver powered by storage batteries—a simple electrical circuit. The receiver incorporated a recording mechanism—a pencil mounted over a roll of paper moved by a small motor running off the current passing through the wire. The centerpiece was a collection of small, thin metal components. Each of these parts ended in toothlike shapes. Each shape corresponded to a numeral from 1 through 10. Inserted into the transmitter, a form or group of forms momentarily completed the circuit. When that electrical impulse reached the receiver, the paper rolled and the pencil recorded the impulse as squiggles corresponding to the metal pieces temporarily mounted in the sending unit. The digits sent were the digits received. Morse saw in this crude assemblage the possibility of standard combinations of squiggles and spaces representing information. The system needed to be more reliably decipherable, but Morse nonetheless scheduled a demonstration for September 2, 1837.

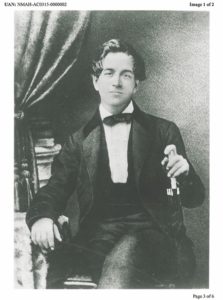

Morse’s spectators at his NYU event that Saturday included Alfred Vail, 29. An NYU alumnus—he had studied theology—the New Jersey native was visiting campus when he happened upon the presentation by Morse, whom he had known casually in his student days. The younger man was struck, he later wrote, by “the germ of what was destined to produce great changes in the condition and relations of mankind.” After the demonstration, Vail asked Morse if he intended to take his experiments further. Morse said he hoped to do so but admitted he needed help. Vail offered to throw in with him. In bed that night, Vail’s head filled with images of “the mighty results which were to follow the introduction of this new agent in meeting and serving the wants of the world.”

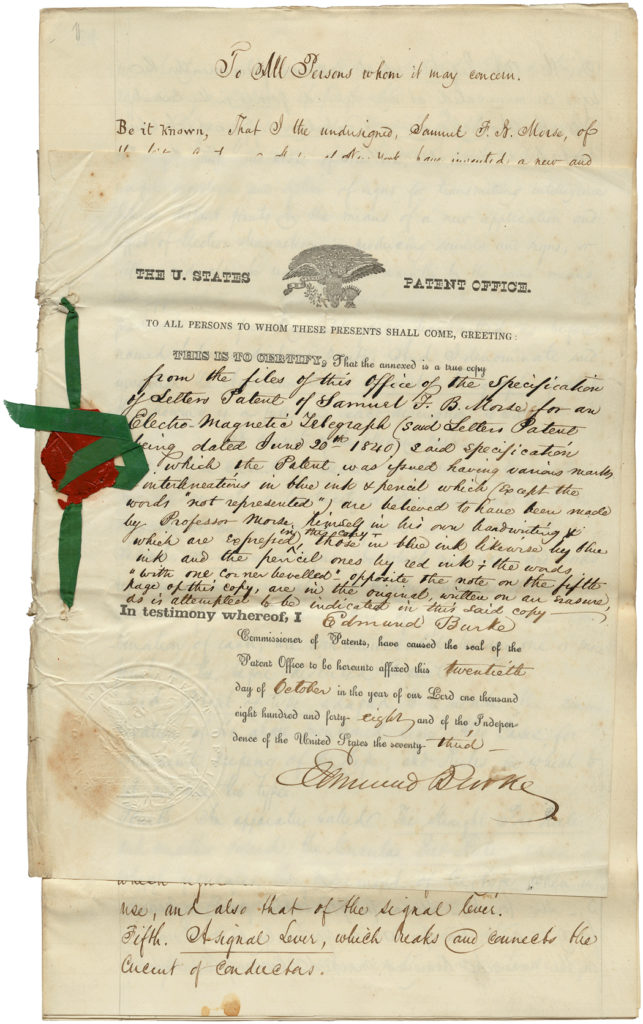

On September 23, 1837, Morse and Vail entered into a written partnership agreement. Morse would file for telegraph patents in his own name. In exchange for making good on a promise to “put into successful operation” a telegraph system, Vail would get a percentage of the venture. Expenses for the project were to be “defrayed by the said Vail,” who agreed to “devote his time and personal services faithfully to this object without charge.”

A slight fellow of medium height, Vail projected modest amiability. However, he was both a scholar and a skilled machinist, and with access to capital to boot. His father, Stephen Vail, served as a judge in Morristown, New Jersey, a village of 2,500 about 25 miles west of Manhattan. Judge Vail owned the prosperous Speedwell Iron Works, also in Morristown. Speedwell’s inventory, according to a catalog, consisted of “Mill-Irons and Machinery of Every Description.” The first steamship to cross the Atlantic had incorporated Speedwell parts. In his youth, Alfred had worked in the factory.

Morse, in his studio in New York City, put on his thinking cap. Government interest, he believed, would mean funding, wealth, and acclaim for whoever could make telegraphy practicable. Congress, which had asked Treasury Secretary Levi Woodbury to study “a system of telegraphs for the United States,” had been talking about funding a telegraphy demonstration between Washington and New York, a concept lately scaled down to a line linking the capital to Baltimore, 40 miles away. Morse wrote to Woodbury on September 27, 1837. Claiming to have developed the means with which to build such a network, Morse offered to make “any sacrifice of personal service and time to aid in its accomplishment.”

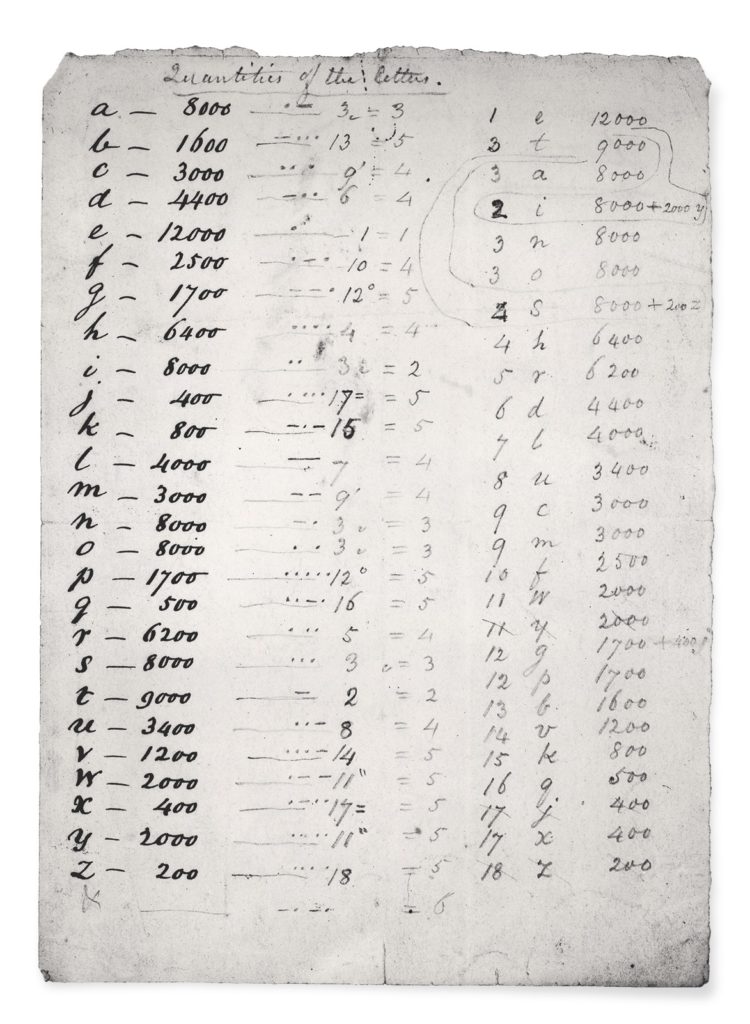

Vail and Morse had in hand the wire and the electricity. They needed a language. Morse decided a code was the ticket. He would assign each word in the English dictionary a number, whether a single digit or multiple digits. Each word would be associated with a piece or combination of pieces of the sawtooth type he had designed. Handed a message in plain text, an operator would consult Morse’s verbonumeric glossary and word by word translate the message into a series of numbers, then convert the numbers into groups for transmission. An operator receiving that transmission would convert the sawtooth sequences back into numbers and then into words. The message “215 36 2 58,” for example, meant “successful [215] experiment [36] with [2] telegraph [58],” according to Morse’s records. By October 1837, Morse had completed his verbonumeric dictionary. “You cannot conceive how much labor there has been, but it is accomplished, and we can now talk or write anything by numbers,” he wrote. A patent application Morse filed that month referenced “a dictionary or vocabulary of words, numbered.” However, Morse’s dictionary had huge gaps: there were no numbers corresponding to names of people or places. The code was also cumbersome. A word converted into a three-digit figure, for example, required the operator to rig three pieces of sawtooth type in the transmitter and the receiver to track down three numbers in the glossary.

Word got around Morristown of the telegraphy venture at Speedwell. Associating electricity with thunderstorms, villagers mocked Vail and his “lightning machine,” ridiculing what they saw as the “solitary instance of bad judgment on the part of the Vails.” Alfred Vail struggled with technological hurdles, such as designing and building a battery strong enough to power the telegraph over long distances. Judge Vail grew impatient. Fearing his father would stop the cash flow, Alfred hid in the workshop.

The pencil-based recording system proved troublesome; the partners switched to a pen nib fed by an ink reservoir. In January 1838, Vail and Morse were ready to test their telegraph. Baxter and Vail strung the Speedwell workshop with two miles of insulated 1/16” copper wire. While he and Morse waited, Vail sent Baxter to fetch his father. “I did not stop for my coat, although it was in January, but ran in my shop clothes as fast as I could,” Baxter wrote later. In the workshop, Judge Vail dictated a message—“A patient waiter is no loser.” (Morse’s glossary has been lost; the conversion is not known.) When that slogan reached the receiver and Morse correctly decoded it, Judge Vail “overcame his usual gravity and he burst into loud and hearty laughter that seemed to come from the warmest cockles of his heart.”

On January 6, 1838, the partners staged a public show for a considerable crowd, generating enthusiastic coverage. “It is with some degree of pride, we confess,” the Morristown Journal reported, “that it falls to our lot first to announce the complete success of this wonderful piece of mechanism, and that hundreds of our citizens were the first to witness its surprising results.” That day’s message, “Railroad cars just arrived, 345 passengers,” hinted at the system’s commercial potential, but Morse’s crude, time-consuming code rankled Vail.

Readying a message for transmission took as long as a printer did to set a block of type, and deciphering a message meant leafing back and forth in Morse’s arcane dictionary. “Alfred’s brain was at this time working at high pressure and evolving new ideas every day,” Baxter recalled. One incentive was an appointment Morse hoped to arrange in Washington, DC. He had in mind to try to snag funding and take on the DC/Baltimore telegraphy test. However, before pitching their scheme, Morse and Vail needed an easier way to send messages.

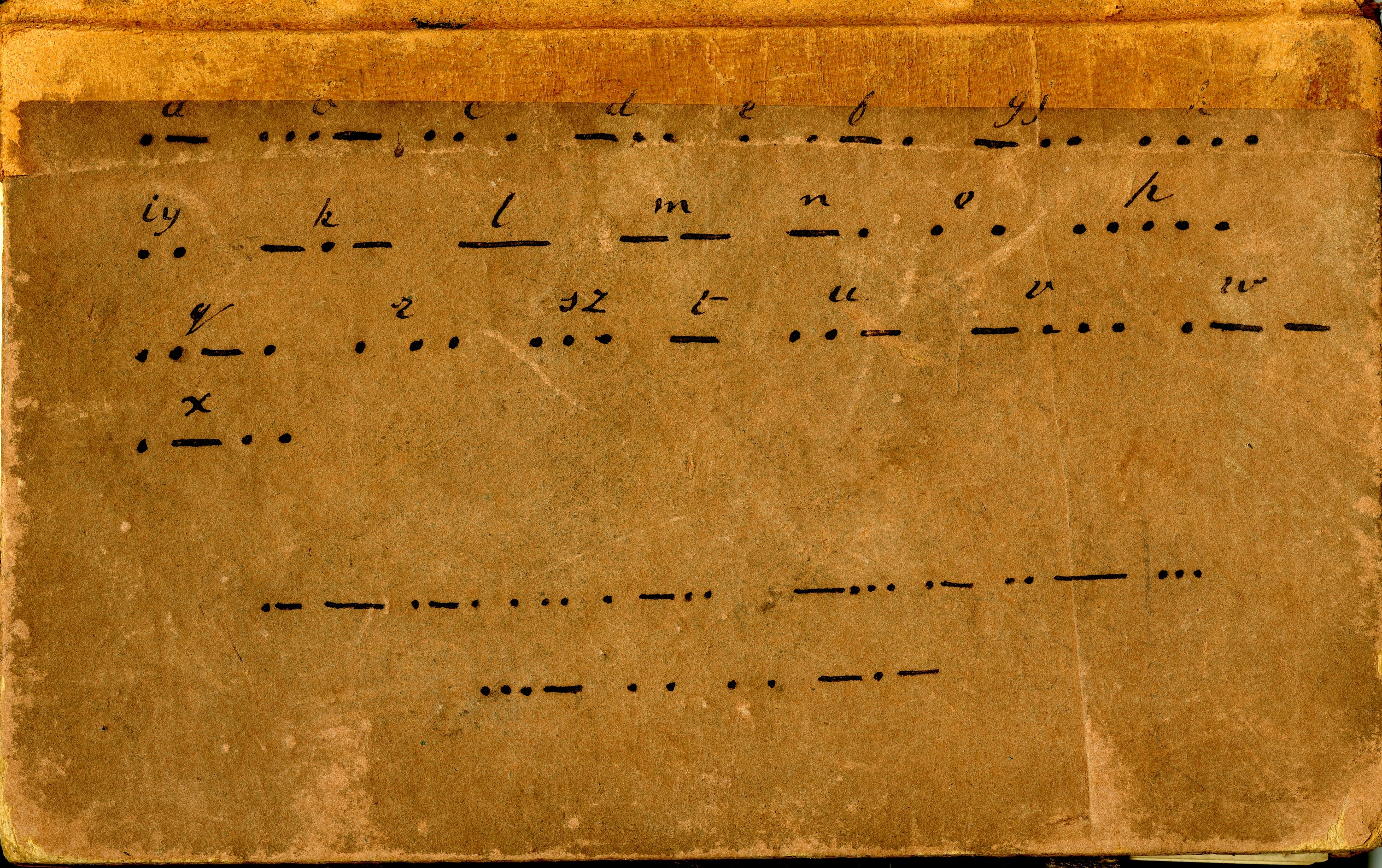

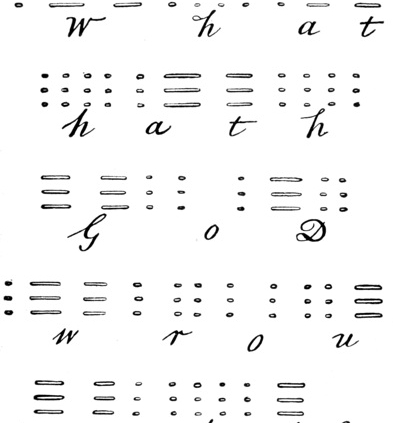

The easier way came to Vail “like a flash,” he later recalled. Instead of groups of numerals representing words, combinations of simple symbols could represent letters and numerals. “A plan might be devised, by means of which the letters of the alphabet could be employed in recording telegraphic messages,” Vail wrote. He decided on dots and dashes. By combining these basic symbols, one might represent words, including names and numerals, character by character. Once an operator mastered the dot-dash alphabet, he could key in words as fast as his mind and fingers allowed. That bulky dictionary and time-consuming double translation would vanish. The most common letters would get the shortest symbols. Asking around at a local newspaper, Vail learned that printers ranked type by frequency of use; the most frequently occurring letters were closest at hand. Vail did likewise, assigning “e,” the letter occurring most frequently in English, one dot. Using the same mechanical pen-and-paper reception mechanism, Vail’s alphabet worked more than twice as quickly as Morse’s system.

The inventors returned to NYU, demonstrating their system on January 24, 1838, this time stringing 10 miles of insulated wire. The invitation-only event went to the city’s “most learned and influential citizens,” one of whom offered a test message: “Attention the Universe! By Kingdoms, Right Wheel!” Morse keyed in the exclamation using dots and dashes. The words came through beautifully.

“Our audiences were astonished and delighted,” Vail wrote.

In publicizing the latest demonstration, Morse clearly signified that he regarded Vail as a second banana at best. Vail money paid for the printed invitations, but those invitations bore only Morse’s name. News reports credited Morse with the dot-dash alphabet and quoted him referring to Vail as his “assistant.” When Vail protested, Morse offered the shaky rationale that he understood “assistant” to mean “colleague” or “partner.” After a similarly successful demonstration in Philadelphia, the partners went to Washington, DC. Leaving Vail to languish in his $10-a-week boardinghouse room, Morse called on President Martin Van Buren and other officials. “Prof. M…appears unwilling that I should accompany him to see any of the Great Folks,” the younger man lamented.

At the U.S. Capitol, the partners rigged 10 miles of insulated copper wire; instead of Vail’s new code, however, they reverted to Morse’s. Despite the clumsiness of the multiple translations, Vail marveled to see “members of Congress eager to witness the powers of the machine, and, after having seen them, utter exclamations of wonder and amazement.” The House Commerce Committee recommended appropriating $30,000 for a DC/Baltimore test line, calling the project “one of such universal interest and importance, that an early action upon it will be deemed desirable by Congress.” So impressed was committee chairman Representative Francis O.J. Smith (D-Maine) that he resigned his House seat to go into business with Morse and Vail. On February 21, the two reprised their words-and-wire show for Van Buren and his cabinet. The president whispered a message to Morse, who sent it to Vail. When Vail deciphered and read aloud the phrase—“The enemy is near”—Van Buren was sold. Congress, however, balked at voting the $30,000.

Awaiting a change of federal heart, Morse traveled to Europe to apply for patents related to their endeavor. Vail returned to Morristown to solve problems. Despite the obvious utility of dot-and-dash, the system remained agonizingly slow. Inspired by musical instrument keyboards, Vail built a sending key. This simple sprung lever ended in a metal button poised over a contact point connected to the transmission wire. Touching the button completed the circuit and sent a signal. Depress the key, as one would on a piano, and an image appeared at the other terminal. A brief touch produced a dot, a longer press made a dash. “William, we can make a single key and play it in perfect time as easily as a piano,” Vail told Baxter. Vail had conceived an alphabet that worked so well that Morse incorporated it into an amendment to his patent, arguably the first for software.

Morse’s European sojourn was less productive. The British attorney general reasoned that, given America’s vastness, Morse should be satisfied with his domestic patent, and declined to issue a British counterpart. A patent in France was pointless; the government there controlled communications. Judge Vail was tapped out.

Morse revisited Capitol Hill on December 6, 1842, asking again for money to build a Washington-Baltimore telegraph. The House Committee on Commerce assented. The panel said the telegraph’s “capability of speedily transmitting intelligence to great distances…is decidedly superior to any of the ordinary modes of communication in use.” In March 1843, with Morse sweating in the gallery, Congress voted to spend the elusive $30,000. “Now the telegraphic enterprise begins to look bright,” Morse wrote to Vail. The telegraph was to follow the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad right of way known as the Washington Branch past Maryland towns like Bladensburg, Beltsville, Contee’s Station, and Laurel.

Vail and Morse had been demonstrating their system under highly controlled conditions. Now they faced reality. Their 16-gauge wire, insulated by coating a layer of cotton with shellac, had to pass through 40 miles of lead pipe installed by fellow inventor Ezra Cornell. Cornell, later to lend his name to a university, would bury the line using his patented pipe-laying device. However, after putting down only 10 miles of line, Cornell reported that the wire’s cotton-and-shellac insulation was breaking down. This decomposition allowed moisture to reach the copper, causing corrosion that shorted out the electrical circuit.

Word of this flaw could stampede Congress away from telegraphy. Morse and Vail stalled for time to address the problem. Cornell “accidentally” damaged his pipe-laying machine and made sure newspapers reported his “accident,” buying Vail and Morse intellectual elbow room. They decided to string their wires aloft, mounting them on chestnut tree trunks felled, limbed, sized, and left with bark intact. “Just imagine,” Alfred wrote to his wife, Jane, “posts, 200 feet apart, along the railroad with two wires stretched between them.” Workers dropped and processed hundreds of trees, securing the resulting 30-foot poles by burying one end four feet deep, 26 or so trunks per mile. By spring 1844, the procession of wired trunks had reached Annapolis Junction, Maryland, 22 miles from Washington. On May 1, the Whig Party, convening in Baltimore, nominated a presidential ticket of Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen. Vail, hearing that information at Annapolis Junction, telegraphed a report to Morse in the capital. By the time Whig delegates reached Washington bearing news of the nomination, the nomination was no longer news.

Workers completed the Baltimore/Washington connection. On May 24, 1844, Morse set up for a ceremonial transmission in the elegant, high-ceilinged Supreme Court chambers. As a choice of message, Annie Ellsworth, Morse’s reputed sweetheart and daughter of Patent Commissioner Henry L. Ellsworth, picked biblical line 23 of book 23 in Numbers. At 9 a.m., Morse tapped, “. – – . . . . . – – . . . . . – – . . . . – – . . . – . . . – – . . . . . . . – – – . . . . . (“What hath God wrou.”) Vail, at the B&O rail terminal in Baltimore, confirmed receipt by transmitting the message back to Morse. “The system has been fully and satisfactorily established,” acting Treasury Secretary McClintock Young reported to Congress on June 4.

Vail feared a private ownership of telegraphy would unleash an army of chiselers. If telegraphy came to be “controlled by vicious or designing men, what an amount of evil may they not inflict,” he wrote, advocating a government-run system. Congress disagreed, voting in February 1845 to spend no more on telegraphy, not even to extend the test line to New York City. Capitalism kicked in. By 1848, the United States had 2,000 miles of privately financed telegraph lines; by 1850, 12,000 miles. Entrepreneurs were marketing a dazzling array of telegraphy equipment. Former Congressman Francis Smith, whose decision to leave Congress never paid off as well as he had hoped, published a book on how to keep messages secret by scrambling them. Unexpected applications emerged. On June 1, 1846, Vail, owing $20 to a Mr. Lily in Washington, DC, deposited cash in that sum at his bank in Baltimore. He telegraphed the bank’s Washington branch, instructing tellers to pay Lily his $20: online banking.

Hustlers did materialize, infringing on patents, flinging lawsuits, confecting shady deals. By 1848, Vail had had enough. A guppy among piranhas, he “bid adieu to the subject of the telegraph, for some more profitable business,” and returned to Morristown. Never wealthy, he lived modestly in semi-retirement, dying at 51 on January 18, 1859. “Even some portions of the Telegraph which I invented, have never been publicly awarded to me,” Vail wrote to a friend in 1852. “I consider myself as not fairly treated…”

Telegraphy grew exuberantly, with operators using Vail’s simple dot-and-dash alphabet to dit and dah with blazing speed. Morse’s cumbersome dictionary was relegated to the dust bin of unworkability. Telegraph lines stitched the nation into a communicative whole. The decoded message, printed out, came to be called a telegram, often carried to recipients by uniformed runners, some of whom offered the option of having the message sung. In 1858, a telegraph cable connected Newfoundland and Ireland, leaping the Atlantic by creeping along the seabed. As of 1861, the East Coast and the West Coast could exchange telegrams. During the Civil War, more than 15,000 miles of telegraph lines were erected for military use. President Abraham Lincoln often visited the War Department telegraph office to get battlefield updates. Among innovations soon to follow and eclipse telegraphy was telephony, which would enable users to converse while separated by hundreds, even thousands, of miles. In telephony as in telegraphy, opportunity abounded. Alfred’s cousin, Theodore N. Vail, started as a telegrapher and by 1885 was president of the American Telephone & Telegraph Company.

Francis Smith, who had left Congress to partner with Morse and Vail, died bankrupt in 1876. Morse got rich and in the public imagination became and remains the inventor of the two-symbol code. However, after Morse died in 1872, Vail began to get his due. Author Frederick Brent Read wrote in 1873 that Morse’s partner had “invented an entirely new alphabet, which he had the genius to foresee.” The Electrical Engineer, an industry periodical, termed Vail’s alphabet “an original and independent invention.”

Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute, site of an early Morse/Vail demonstration, declared that “to Vail is also justly due the credit of devising the conventional alphabet of dots and lines, which has become the universal telegraph language of the world.” The Century lamented that Vail’s invention of the dot-dash code “has never met with the appreciation which it deserves.” Baxter, Vail’s assistant, wrote in detail about how his boss had invented his alphabet and the telegraph key. William P. Vail, Alfred’s uncle, recalled that his nephew had told him of inventing the code. New York Sun editor Moses S. Beach, a friend of Vail and Morse, told a similar story. Only The Electrical World, in 1895, credited the code to Morse.

In 1887, when a newspaper story about telegraphy characterized Alfred Vail as a nameless “bright young fellow,” a new generation entered the fray. Stephen Vail, eldest of Alfred’s three sons, sent the editor a lengthy recitation of his late father’s contributions. Angered at an 1894 article’s “very cursory mention” of his father, the son wrote to that publication’s editor demanding “the courtesy of sufficient space in your valued journal” to correct the record. In an 1899 letter to yet another editor, Stephen Vail complained that “the world has been taught to believe that there was but one name connected with the invention of the telegraph.”

Stephen Vail’s campaign annoyed Edward Lind Morse, Samuel Morse’s youngest son, who in a letter to The New York Times dismissed Vail’s claims. Samuel Morse, Edward wrote, “is too firmly established to be injured by such a series of falsehoods and

distorted facts.” Vail volleyed, accusing Samuel Morse of having allowed “no opportunity to escape in which he might obliterate all record of Alfred Vail’s connection with the invention.”

These bitter personal exchanges ended in 1909 with Stephen’s death, but hard feelings lingered.

In 1911, 52 years after Alfred Vail’s death, J. Cummings Vail, another of the inventor’s sons, updated his father’s grave marker at St. Peter’s Church in Morristown to read “INVENTOR OF THE TELEGRAPHIC DOT AND DASH ALPHABET.” Edward Morse angrily demanded that St. Peter’s remove the phrase. The rector declined, noting that the Vail family owned the stone. Edward Morse kept up the fight. In 1920, when the New York Tribune attributed the dot-dash alphabet to Vail, Morse complained in exasperation that he thought he “had long ago put a quietus on that hoary misstatement of fact.” Death ended his advocacy in 1923.

Except at his grave, where weathering has rendered the corrective inscription barely legible, Alfred Vail is largely forgotten, mentioned if at all as Morse’s assistant, a diminution about which Vail himself was philosophic. “I do not seek renown for myself,” Vail wrote in 1853. “I care little for the world’s applause, which at best is very hard to maintain even when justly yours, and given often, where they cannot and will not discriminate and justly award.” H

_____

Still Standing

Morristown, New Jersey’s Speedwell Iron Works, whose revenues underwrote the work underpinning the technology, closed in 1873. In 1908, the abandoned ironworks burned down. However, the barn-like building in which Alfred Vail and Samuel Morse demonstrated their system in January 1838 (see p. 38) still stands at 333 Speedwell Avenue. Maintained by the Morris County Park Commission, the structure houses Historic Speedwell, a museum open April through October (morrisparks.net/index.php/parks/historic-speedwell). —Joseph Connor

This story appeared in the June 2020 issue of American History.