What hath God wrought?” Those were the words that the daughter of Henry Leavitt Ellsworth famously suggested Samuel F. B. Morse send from the basement of the U.S. Capitol on May 24, 1844, to officially open the much-anticipated telegraph line from Washington to Baltimore. Ellsworth, the commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office, had traveled extensively in the West before his appointment to the post in 1835 and understood the need for better means of communications to bind Americans together. Consequently, he had taken an interest in Morse’s electric telegraph and been instrumental in getting Congress to provide financial assistance.

It didn’t take long for Ellsworth’s and Morse’s efforts to pay off. By 1850, some 20 companies were operating about 12,000 miles of telegraph lines in the United States, and it was soon clear that the telegraph would have a profound effect on all aspects of human activity—not least the conduct of war. In the mid-1850s, the British and French governments relied on the telegraph to help them manage and monitor their forces in the Crimean War. British authorities also used the telegraph in responding to the Indian Rebellion of 1857, as did Napoleon III’s government in supporting the French operations in Italy that culminated in the Battle of Solferino in 1859.

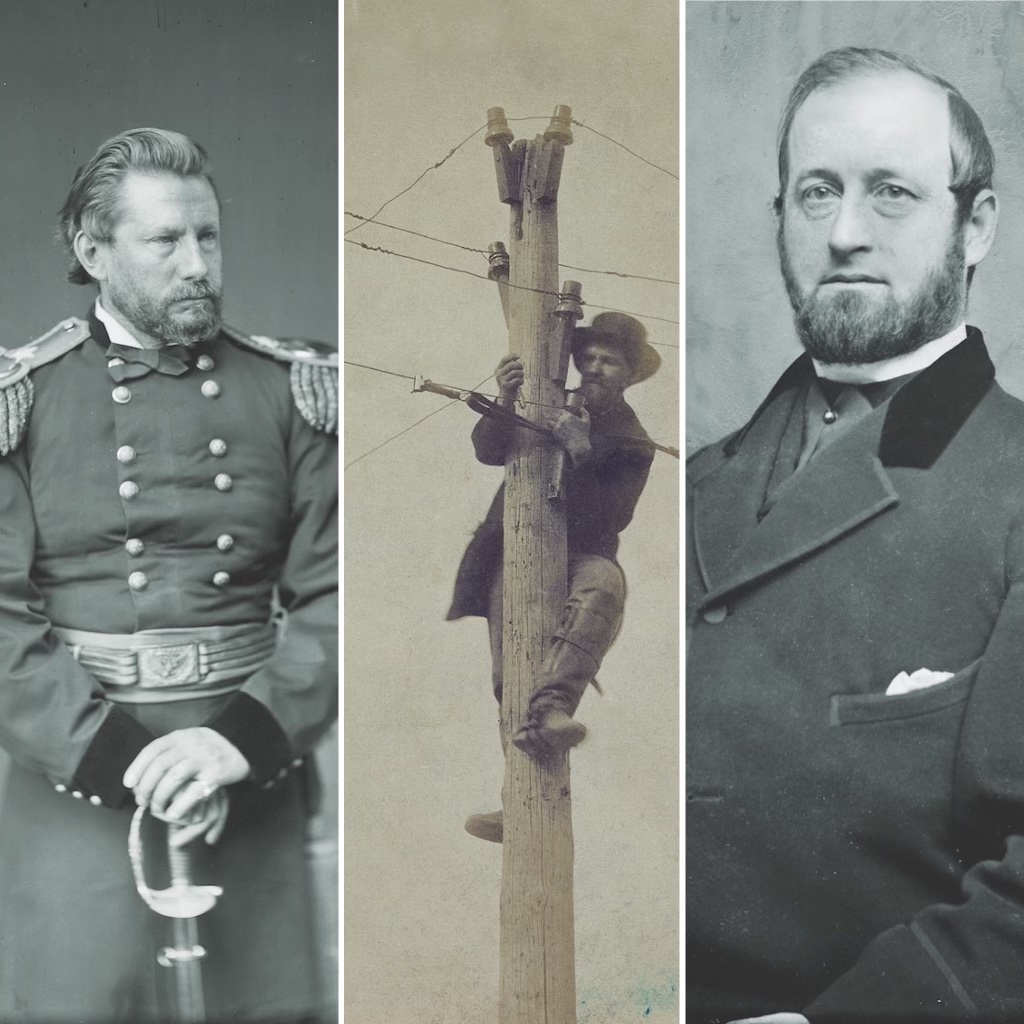

A few years later, to the great fortune of the Union effort in the Civil War, the U.S. government found men with the technical knowledge and administrative ability needed to manage new technologies and far-flung enterprises. While those who fought on the battlefield would be celebrated in art and literature, the many bureaucrats who also shaped the course and outcome of the war went unheralded. Among the most important of these was Anson Stager.

Born in 1825 in Ontario County, New York, Stager began his working life at age 16 as an apprentice at the Rochester Daily Advertiser. The newspaper’s publisher, Henry O’Reilly, was an early backer of the electric telegraph. After constructing a line in Pennsylvania that linked Philadelphia with Harrisburg, he tapped Stager to be one of its operators, and before long Stager was running the telegraph office in Lancaster. In 1848 Stager moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, to serve as chief operator of the telegraph company there, and over the next eight years he worked to consolidate the vast network of lines serving the area into a single system.

In 1856 Stager moved to Cleveland to become the general superintendent of the Western Union Telegraph Company. Under his leadership, Western Union developed a close working relationship with the railroads, and by 1860 it had secured an effective monopoly over the lines connecting the Mississippi River with the cities of the Eastern Seaboard and the Ohio River to the Great Lakes.

When George B. McClellan, a Cincinnati railroad executive, assumed command of the military forces Ohio raised in the aftermath of the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861, he wasted little time seeking out Stager. Six years earlier, McClellan had served on a commission that the U.S. War Department sent to the Crimea, where the British Army was laying an underground telegraph cable from its headquarters to the front lines at Balaklava and a submarine cable of nearly 340 miles that linked Balaklava to Varna in Bulgaria across the Black Sea.

These were impressive accomplishments, but before long military leaders would find the telegraph to be a mixed blessing, as it could be both a tool for communication and a source of disruption. Its value for command and control in conducting operations was inestimable. Yet the telegraph also enabled newspapers to gather and present to a mass audience reports on how soldiers on the front lines endured unsanitary trenches and hospitals while officers were living in comfort on yachts. “The confounded telegraph,” a British general groused, “has ruined everything.”

When he assumed command in Ohio, McClellan understood that the ability to manage and control the flow of information would be vital not only to conducting operations but also for maintaining a healthy connection between the military and the home front. Within a few weeks Indiana and Illinois came under his command as well. Fortunately, their governors had taken steps to ensure that the telegraph lines in their states were secure and responsive as the North girded for war with the South.

Stager soon proved that McClellan had made a wise choice in appointing him “superintendent for military purposes of all telegraph lines within the Department of Ohio.” In May 1861, McClellan ordered his forces across the Ohio River to rescue the Unionist population in western Virginia and secure control of the vital railroad junction at Grafton. Although the Union forces didn’t take telegraph equipment with them, the lines already in place got messages to McClellan more quickly, and allowed him to communicate with his commanders more quickly, than otherwise would have been the case. Consequently, thanks to Stager’s efforts, McClellan was able to effectively oversee the operations that produced the North’s victory at the Battle of Philippi on June 3, 1861.

When McClellan left Cincinnati a few weeks later, Stager made sure that the telegraph came with him. McClellan was thus able to adjust his plans three times in three days as he directed operations that produced victories at Rich Mountain and Corrick’s Ford in Virginia. With the telegraph supporting his operations as well as ensuring that the Northern press was aware of them, McClellan became one of the first Union military heroes and found himself summoned to Washington to take command after the Union’s defeat at First Manassas in July. “The experiment proved successful,” Thomas B. A. David, Stager’s right-hand man, crowed, giving McClellan capabilities “unparalleled in military history.”

When the Civil War broke out in April 1861, the U.S. government had no office or department responsible for overseeing telegraph operations. That same month Secretary of War Simon Cameron recruited Thomas Scott, the vice president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, to organize a U.S. Military Telegraph Corps. Scott brought four telegraph operators from his company to Washington and stationed them at the War Department, the Navy Yard, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot. As these men went to work, Edward S. Sanford, the president of the American Telegraph Company, which was responsible for the lines connecting Washington with the rest of the North, out of patriotic duty effectively ran and paid for the telegraph system. (Congress reimbursed him later.)

In October 1861, Scott persuaded President Abraham Lincoln and Cameron to call Stager to Washington. After hearing Stager’s ideas, Cameron made him a captain in the Quartermaster Department, and on November 25 named him general manager of the military telegraph lines. McClellan had been appointed commanding general of the entire Union army a few weeks earlier, and with his support Stager went to work implementing his plans. In February 1862, the same month Lincoln gave the government authority over commercial telegraph lines, Stager was promoted to the rank of colonel.

Shortly after offering his services in Ohio, Stager, immediately realizing the need to protect the critical military information being transmitted over telegraph lines, decided to prepare a cipher. Impressed with what Stager had produced, McClellan asked him to develop one for field operations. Stager’s relatively simple but effective cipher was the first of 12 developed for the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps (though only 10 of them were actually used) and adopted by the War Department. The cipher was known only to actual telegraph operators who were strictly enjoined not to reveal it to anyone else.

Stager’s efforts, however, would be complicated by McClellan’s decision in August 1861 to appoint Albert J. Myer signal officer for the Army of the Potomac. Like Stager, Myer was a native of New York who at a young age had developed a fascination with communication technologies, working as a telegrapher before attending medical school. After securing appointment as an army surgeon in 1854, Myer developed a wigwag system of communication while stationed in Texas that used signal flags during the day and lanterns or torches at night.

In 1859 the War Department assembled a board headed by Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee to evaluate Myer’s innovations. In June 1860, after a series of field tests proved their value, the War Department directed Myer to organize and lead a new U.S. Army Signal Corps. Shortly after McClellan’s operations in western Virginia compellingly demonstrated the military value of Stager’s work, the Confederates did the same with Myer’s. At First Manassas, one of Myer’s former assistants, Edward Porter Alexander used Myer’s system to inform Confederate headquarters of the Union attempt to turn their left, which enabled Generals Joseph E. Johnston and Pierre G. T. Beauregard to successfully counter it and win the battle.

It didn’t take long for Stager and Myer to butt heads. Myer, something of a martinet, aimed to bring Stager’s efforts under centralized direction to ensure that they were responsive to the military chain of command. Myer also thought that Stager and others with business backgrounds were motivated more by self-interest than a true spirit of public service and did not understand the workings of the military. Myer thus decided to persuade Congress to authorize a permanent, independent Signal Corps.

Despite holding a commission in the army, Stager, who had only placed his talents and resources at the service of the government in response to the secession crisis, wished to maintain maximum independence for himself and his operators. Indeed, he continued to spend most of his time in Cleveland attending to his duties as Western Union’s general manager. Consequently, the man actually responsible for overseeing the operations of the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps in Washington for most of the war was Major Thomas T. Eckert. Like Stager, Eckert had worked as a telegraph operator and was in Cleveland when the war began. After offering his services to the War Department, he was assigned to McClellan’s field headquarters until September 1862, when he was ordered to Washington to be Stager’s man in the capital.

Both Stager and Eckert brought to their duties well-honed bureaucratic and political skills that the more rigid and soldierly Myer did not possess. This enabled them to cultivate a powerful ally in Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a former corporate attorney who came to view the telegraph as his “right arm.” It also didn’t hurt that Stanton developed an intense dislike for McClellan and other Regular Army officers and that Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs, in whose department Stager and his operators held their commissions, was a Stanton ally.

Stager and Eckert surely boosted their cause when they cooperated with Stanton’s effort in early 1862 to relocate the military telegraph office from McClellan’s headquarters to the War Department library (which was, conveniently, next to Stanton’s own office). What’s more, President Lincoln liked spending time at the telegraph office at the War Department, finding it not only a useful place for monitoring events but also a refuge from his many other cares, where he could be at ease and, he said, “escape my persecutors.” Lincoln and Stanton especially appreciated how, in conspicuous contrast with the rigid formality of Myer and other uniformed officers, Eckert and the other telegraph operators were welcoming hosts who enjoyed sharing meals with the president, listening to his anecdotes, and indulging him when he took an interest in their work.

McClellan had so many other problems to deal with that he took little interest in resolving the jurisdictional dispute between Myer and Stager. Myer turned to Henry J. Rogers, a former associate of Morse’s, to organize wagon trains to carry telegraph sets and their equipment, Thanks to the efforts of Eckert and Rogers, the telegraph admirably kept McClellan in touch with his civilian superiors in Washington throughout his 1862 campaign on the Virginia Peninsula. But the telegraph, while an effective tool for long-distance communication between Washington and various field headquarters, was too complex and delicate a machine to manage operations at the tip of the spear. This, as historian Edward Hagerman notes, should have led to a “common-sense division of authority” between Myer and Stager, with the former responsible for communications between tactical units in the field and the latter for communications between department and army headquarters and between them and Washington.

Stager, however, wanted his division of civilian telegraphers to be independent of Myer and responsible for all communications employing the telegraph. For his part, as he worked to refine a semaphore system for use in the field, including a cipher disc that facilitated changing codes when necessary, Myer countered by supporting efforts to develop a portable telegraph, with its own alphabet and codes, that could be taken to the field. In 1862 Myer successfully pushed for the adoption of the portable Beardslee Patent Magneto-Electric Field Telegraph, which paved the way for Congress, in March 1863, to establish the Signal Corps as a permanent and independent branch of the army.

Unfortunately for Myer, the Chancellorsville Campaign demonstrated that the Beardslee, for all its technical merits, was not durable or reliable enough for battlefield use. The subsequent Gettysburg Campaign, however, proved the worth of having two separate systems: The Military Telegraph Corps handling higher headquarters and the Signal Corps managing battlefield messages. On November 10, 1863, with Stanton and his allies in the telegraph corps making it plain that they had had enough of Myer, Lincoln ended the dispute by ordering Myer to turn over all telegraph equipment to Eckert. Myer was also relieved of his duties as chief signal officer and reassigned to duty in Tennessee. (Myer would return to Washington after Congress, at the behest of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, reorganized the Signal Corps in 1866 and made him chief signal officer.)

Although it operated under the authority of the War Department, the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps, in keeping with Stager’s vision, relied on private telegraph companies to transmit messages and to establish lines on its behalf. Many of the more than 1,000 telegraph operators in the corps were not even 20 years old, and 33 of them lost their lives in the war. Another 175 were either wounded or captured.

At the end of the Civil War, Stager was promoted to brevet brigadier general. His office had handled more than six million messages and directed the construction and operation of more than 15,000 miles of telegraph line. In 1862 alone, Stager reported, his operators handled some 1.2 million telegrams. By the end of 1864, the Union was spending more than $93,000 a month on telegraph services. (In comparison, an official of the Confederacy estimated that it was spending less than a tenth of that amount.)

It is unfortunate, though perhaps not surprising, that Stager is rarely accorded a place of prominence among those whose efforts were critical to the North’s victory in the Civil War. Nonetheless, his contributions—and those of the men working under his direction—were immense. In concert with the railroad and steamship, the telegraph enabled the United States to undertake an exercise in military power projection from 1861 to 1865 that was unprecedented in the American experience and, like the communication revolution of which the telegraph was a major part, served to bring about a more perfect Union. MHQ

Ethan J. Rafuse is professor of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.