Major General George B. McClellan—the general with the “slows.” Even among those unfamiliar with Civil War history, that is how McClellan is usually remembered, as the commander President Abraham Lincoln had to prod into action. The aftermath of the Maryland Campaign and the Battle of Antietam in the fall of 1862 is often held up as Exhibit A of “Little Mac’s” dithering. McClellan had no plans for another campaign, the common story goes, and more important, he used the excuse that his army was not receiving the necessary supplies to delay launching another campaign across the Potomac River.

The first allegation is easily refuted. McClellan confided to his wife on September 22, 1862, “I look upon the [Maryland] campaign as substantially ended & my present intention is to seize Harper’s Ferry & hold it with strong force. Then go to work to reorganize the army ready for another campaign.”

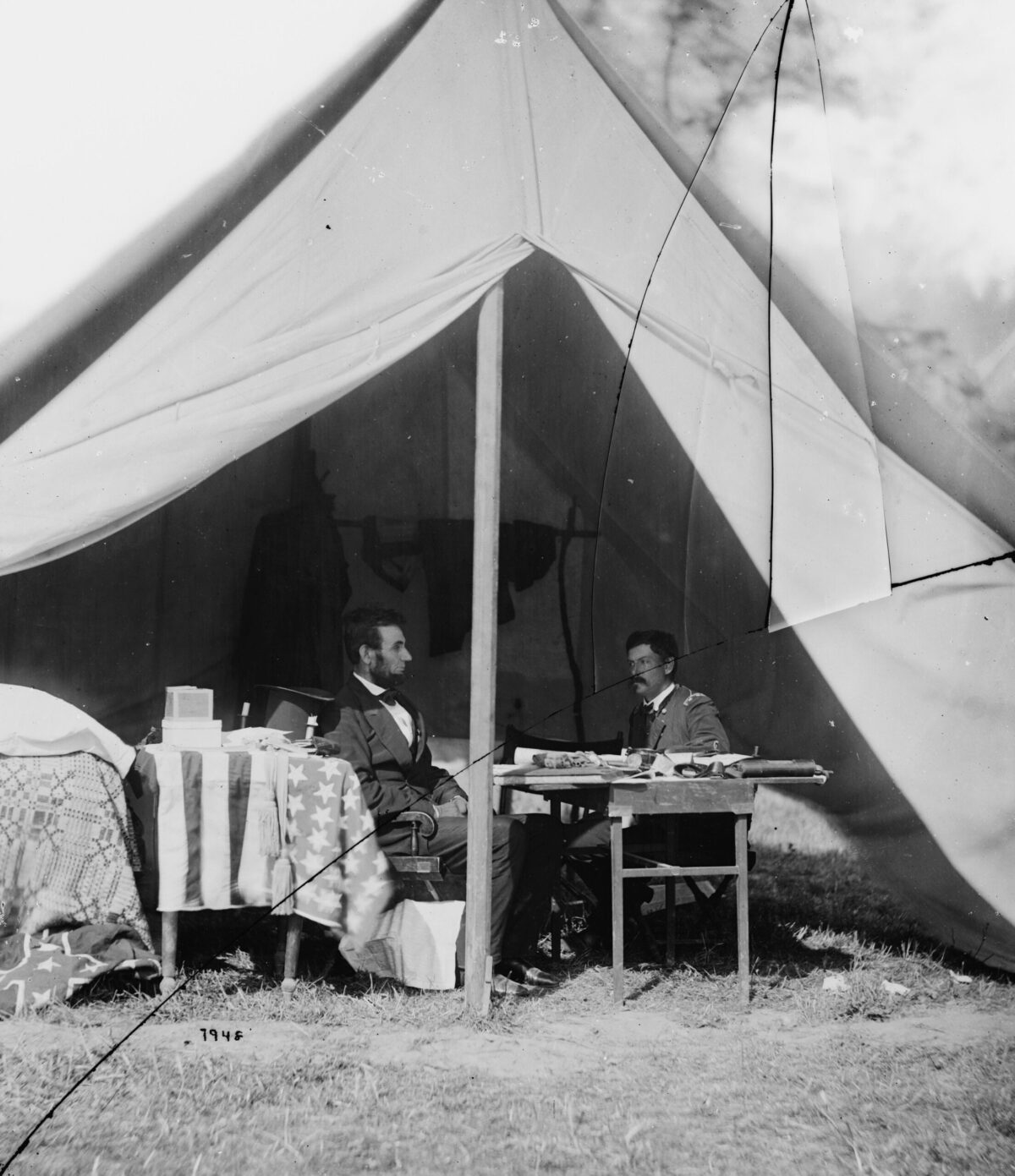

McClellan’s concern about supply shortages is another matter. The oft-told story is that Lincoln did everything he could to push the slow general into action, including a visit to Antietam in early October to personally observe the condition of the army. Two days after his visit, Lincoln issued an order for McClellan to move. Day after day of fine autumn weather passed, however, while McClellan stayed put. Throughout much of October, McClellan constantly complained that his requisitions for supplies had not been met; consequently, it was impractical, if not impossible, for him to cross over his army’s namesake river and take the war back into Virginia. Many Civil War historians dismiss McClellan’s supply crisis as a manufactured excuse for chronic dawdling. Substantial documentation, however, proves that McClellan had a genuine supply crisis.

In the Eastern Theater, the Peninsula, Seven Days, Second Bull Run, and Maryland campaigns had occurred in fairly quick succession, not to mention the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of May-June 1862. Some of McClellan’s men had been on the march since the spring and were in a ragged state. And there are astonishing indications of conspiracy on the part of the War Department to deliberately create McClellan’s post-Antietam matériel shortfall. Conspiracy is admittedly a harsh allegation, but something is amiss after the Battle of Antietam that bespeaks a deliberate cabal against McClellan. Mystery surrounds the situation to the present, but there can be no debate about the fact the Army of the Potomac needed refitting.

The 27th Indiana Infantry of Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams’ 12th Corps, for example, had previously participated in Maj. Gen. John Pope’s disastrous Second Bull Run Campaign. The regiment’s historian, Corporal Edmond R. Brown, described the men’s condition shortly after Antietam: “Many of the regiment were entirely shoeless, pants were out at the seat and knees and frayed off at the bottoms anywhere from the ankles upward. Numbers had no coats, and the coats of others had holes in the elbows, were ripped at the seams, deficient as to tails, soiled and discolored….Our quartermaster sergeant notes in his diary that the regiment was in the worst plight at this time for clothing and shoes of any in its history.”

On September 26, Colonel Charles S. Wainwright, newly assigned chief of artillery of the 1st Corps, recorded “a good deal of suffering among our men for want of clothing, especially blankets and shoes.” Wainwright made a special note regarding the condition of these men in light of their participation in the Second Battle of Bull Run. “The losses in the Pope affair have not been made good yet. Many of the men are quite barefooted, and others are without a blanket.”

Four days later Wainwright noted, “I did not expect we should have remained here so long….But they say that our supplies do not come.” He had gone “up to headquarters again to see if something could be done…but could get no further satisfaction than that they were promised from Washington.” Frustrated, he griped, “This corps has now been two months since receiving any supplies to speak of, and I suppose it is the same throughout the army.”

In early October, Lincoln decided to visit the Army of the Potomac. The precise purpose of the president’s visit isn’t clear. Traditional histories maintain that he wanted to thank the army for its service and confer with McClellan. But it also should have been abundantly clear to the president that there was a supply shortage.

Lincoln traveled to the camps in the Sharpsburg region and met with 9th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Apparently the pair shared the president’s carriage. One of Burnside’s regiments was the 9th New York, and as regimental historian John H.E. Whitney recalled, the men were hungry and restless that autumn. The New Yorkers “had suffered greatly for the want of meat and vegetables, and many of the men for that reason were wholly unfit for duty. They were always assured that there was an abundance somewhere, and that it was coming.”

Another member of the 9th New York, Lieutenant Matthew J. Graham, witnessed and recorded a singular event, a food riot:

It may be interesting to relate an incident which occurred here in the presence of Mr. Lincoln…ever since the manoeuvring and fighting which led up to the battles of South Mountain and Antietam began, food had been so scarce that the men had continued in a state of ravenous hunger….One morning, during the time the President was on his visit to the army, several of the Zouaves found themselves part of a crowd of soldiers surrounding a wagon loaded with bread which was being peddled along the road. Some of the soldiers in the crowd had money and bought, but, alas, some of them had none, and still they wanted the bread. To want and to have are sometimes very closely allied in the army, so a linch-pin was slipped out, a wheel removed, and the whole load upset in the road. A general scramble was made for the scattered loaves and when the tumult was at its height General Burnside’s carriage, in which he was escorting the President on a visit to one of the camps in the vicinity, suddenly appeared in the midst of it…the raiders scattered in every direction, each man, however, clinging tightly to his stolen loaf and endeavoring to put as much ground between himself and the carriage.

The distinguished occupants of the carriage both witnessed the event, and Graham’s last statement about it is noteworthy. “The President neither said or did anything to indicate that he was especially interested in the affair, he simply looked on.”

During his early October visit, Lincoln reviewed many of the soldiers on the field of Antietam. Colonel Wainwright observed, “Lincoln…rode along the lines at a quick trot….The men looked well, considering we have yet been unable to get any new clothing.” Another 1st Corps officer, Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick, also remarked on the troops’ condition: “The Officers and men are without clothing…are ragged and filthy. Many of them have vermin upon them & cannot get rid of them.”

Major Rufus R. Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin noted, “Our battle flags were tattered, our clothing worn, and our appearance that of men who had been through the most trying service….Mr. Lincoln was manifestly touched at the worn appearance of our men.” Another reliable witness was 2nd Lt. Elisha Hunt Rhodes of the 2nd Rhode Island, who noted the president and McClellan’s review in his diary: “In spite of our old, torn and ragged clothes the troops looked well as the lines stretched over the hills and plains.”

A cursory review of the army should have revealed that the men needed supplies, especially shoes and clothing. Unfortunately, the Northern public knew only what they read in the newspapers. The New York Tribune of October 3 succinctly expressed the prevailing view: “The President is in excellent health and spirits, and is highly pleased with the good condition of the troops.”

When Lincoln departed for Washington, D.C., McClellan remembered the president’s last words: “He told me that he was entirely satisfied with me and with all that I had done; that he would stand by me against ‘all comers.’” This was in stark contrast to a message McClellan received from Union General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck on October 6. “I am instructed to telegraph you as follows: The President directs that you cross the Potomac and give battle to the enemy or drive him south. Your army must move now while the roads are good.”

McClellan now had a direct written order by the president, endorsed by Halleck and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, to move into Virginia.

Throughout much of October, McClellan constantly stated that his requisitions for supplies had not been met. It was impractical therefore, if not impossible, for him to advance into the enemy’s country. As colder weather approached, the men began to suffer even more. Consider the plight of the 20th Maine. “The weather became very cold,” wrote Private Theodore Gerrish, “and the bleak, penetrating winds swept with terrible force down the hillsides and through the valleys of Maryland. We had no tents, and for a number of weeks were without overcoats.”

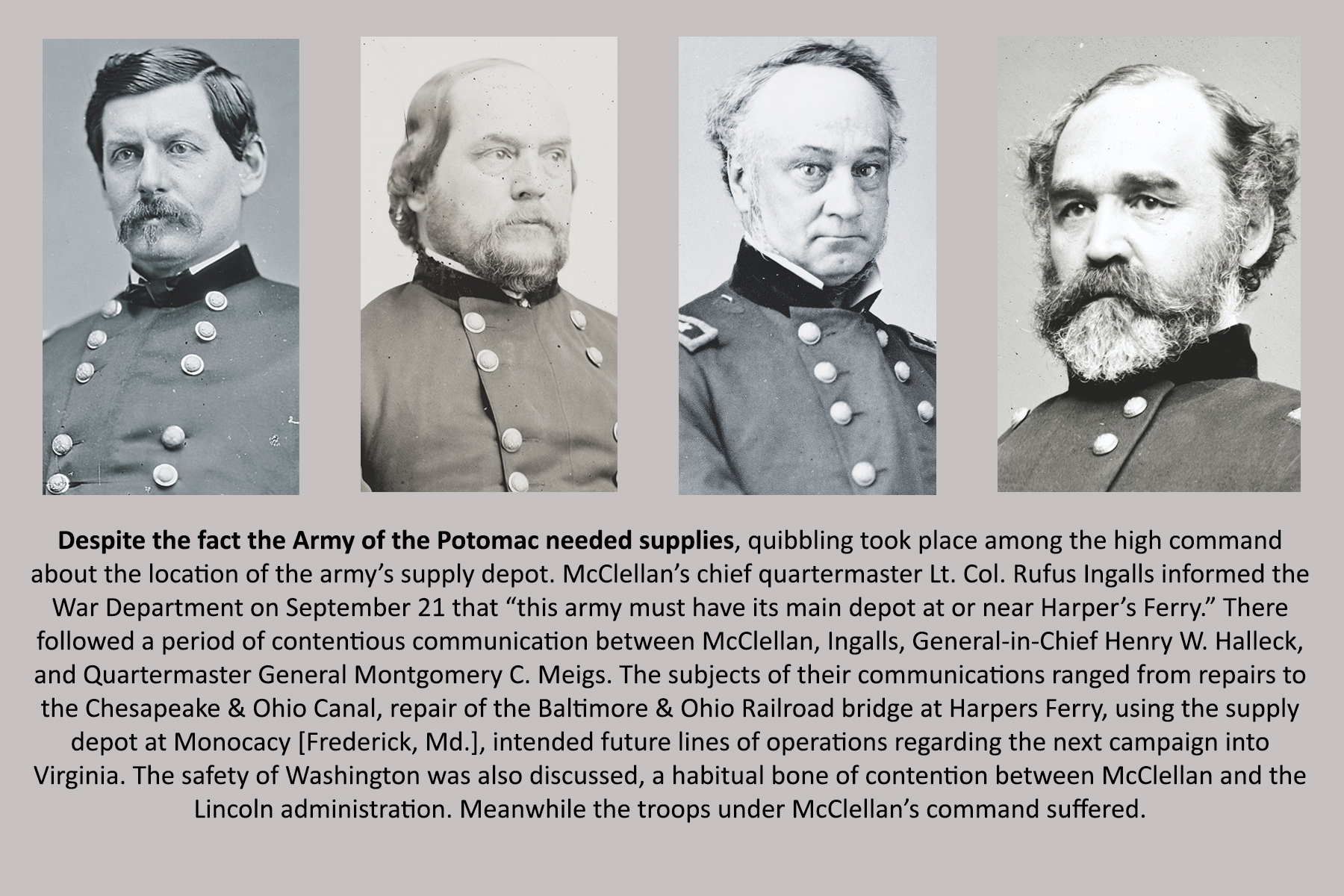

By October 11, McClellan directly called Halleck’s attention to the situation, and referenced the efforts of his chief quartermaster, Lt. Col. Rufus Ingalls. “We have been making every effort to get supplies of clothing for this army and Colonel Ingalls have received advices that they have been forwarded by railroad, but…they come in very slowly.” Later that day “I am compelled again to call your attention to the great deficiency of shoes and other indispensible articles of clothing that still exists in some of the corps of this army.” McClellan told Halleck he had received assurances from the War Department that clothing would be forwarded. “It did not arrive as promised, and has not arrived yet,” wrote McClellan. “The men cannot march without shoes.”

On October 19, a New York Herald correspondent observed:

“They [the army] have not received their fall clothing, are destitute of blankets, tents and raincoats, in fact of all kinds of Quartermater’s stores. Similar conditions prevailed in the ranks of the 155th Pennsylvania, another new regiment: Although within a comparatively short distance (50 or 60 miles) of Washington City, the headquarters of army supplies, the requisitions of Colonel [Edward] Allen for shelter tents, necessary clothing…received no attention whatever from the department at Washington….The Government at Washington seemed incapable of meeting or unwilling to meet the emergency.”

On October 19, Wainwright noted, “We are still here with orders to be ready to move at any hour, but still we are not ready…still the men are very badly off for shoes and blankets.” He also made an uncanny statement, “It seems almost as if they purposely kept them back at Washington, or else they have not got them.” Wainwright was not far off the mark.

On October 23, the interim commander of the 1st Corps, Brig. Gen. George G. Meade, told his son, John:

We are in hourly expectation of marching orders….We have been detained here by the failure of the Government to push forward reinforcements and supplies. You will hardly believe me when I tell you that as early as the 7th of this month a telegram was sent to

Washington informing the Clothing Department that my division wanted three thousand pairs of shoes, and that up to this date not a single pair has yet been received (a large number of my men are barefooted) and it is the same thing with blankets, overcoats, etc., also with ammunition and forage. What the cause of this unpardonable delay is I can not say, but certain it is, that some one is to blame, and that it is hard the army should be censured for inaction, when the most necessary supplies for their movement are withheld, or at least not promptly forwarded when called for.

Alpheus Williams, in a letter to his daughter on October 26, complained, “We are lacking much.” Like so many others, Williams couldn’t explain why:

There seems to be an unaccountable delay in forwarding supplies. We want shoes and blankets and overcoats—indeed almost everything. I have sent requisition upon requisition; officers to Washington; made reports and complaints, and yet we are not half supplied. I see the papers speak of our splendid preparations. Crazy fools! I wish they were obliged to sleep, as my poor devils do tonight, in a cold shivering rain, without overcoat or blankets….I wish these crazy fools were compelled to march over these stony roads barefooted, as hundreds of my men must if we go tomorrow.

The clamor over supplies eventually caught Lincoln’s attention, and he sent Colonel Thomas A. Scott, former assistant secretary of war, to evaluate McClellan’s complaint. McClellan, Scott wrote, had a member of his staff “show me the requisitions, and also a statement of the amount received, and that I could draw my own inferences.” Scott could verify a shortage of “shoes, clothing, and other necessaries for the men.” Upon learning the facts, Scott immediately returned to Washington, and reported his findings to Lincoln, Halleck, and Stanton:

Both Stanton and Halleck then repeated their assurances that all McClellan’s requisitions had been met; and it was suggested that, as the troops in the forts around Washington constituted a part of the Army of the Potomac, the supplies that were intended for McClellan’s army in the field, instead of having been sent to him at Harpers Ferry, had by some means or other been diverted for use of the troops in the fortifications, and thus had failed to reach him. This proved to be the explanation of the trouble.

Scott wrote his incredible story in 1880, 18 years after the fact, and so it is understandable that McClellan’s critics may find it somewhat suspect. Nevertheless, Scott is a primary source, and he does provide a reason for McClellan’s delay in starting a new campaign.

There are other versions of the story from the leadership of the Union 5th Corps. One of them comes from Regular Army officer William H. Powell of Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ division. “Day after day passed without receiving supplies,” he wrote. “General McClellan wrote, telegraphed, urged, and got into a snarl with the quartermaster’s department, the officers of which insisted that the stores had been shipped.” Technically, Powell noted, they had been, and “[t]hat appears to have been what was considered the end of their [Montgomery Meigs’ quartermasters] duty at the time.” Powell didn’t mention Colonel Scott, but he did note where the supplies had gone. Investigation revealed “train loads of supplies for the army…on the tracks at Washington, where some of the cars had been for weeks.”

Powell’s account confirms that as far as the authorities in Washington were concerned, “technically” the supplies had been shipped to the army.

The destitute condition of the army certainly indicates a supply problem. Numerous primary sources document shoeless men shivering in the Maryland countryside. Is it believable that the Union War Department, with all its logistical advantages, was incapable of moving supplies 60 miles or so on an established railroad? Recall Wainwright’s prescient journal entry of October 19: “It seems almost as if they purposely kept [the supplies] back at Washington.” If Scott’s and Powell’s veracity is trustworthy, that is exactly what happened. Was this misdirection of supplies accidental or intentional?

If it was not an accident that supplies bound for the Army of the Potomac on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad ended up in the forts or depots around Washington, then it was a deliberate act to hamper McClellan and there was a conspiracy against the general. The big problem with this explanation is that the conspirators covered their tracks extremely well. On the other hand, a lack of evidence is just what one would expect with a successful conspiracy. Who had the most to gain from the situation, and who was able to engineer the circumstances? One answer would certainly be Secretary Stanton.

Stanton seems to have created what he needed: documentation he could place in front of the president and release to the national media that proved McClellan untruthful. On November 5, a Cabinet meeting was held to discuss the issue. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair provided an account in a letter dated January 21, 1880. As with Colonel Scott, 18 years separated the incident from memory, but also like Scott, Blair is a primary source. The subject of McClellan was discussed in the Cabinet, Blair wrote, and it “was attended by Halleck” who put Stanton’s paper trail to good use. Halleck stated “that the excuses given by McClellan for not moving were untrue. I recollect that in reference to a supply, I think of shoes, which General McClellan had written were indispensable, and had not been received, Halleck undertook to show, by official statements of shipments made, that McClellan had not stated the truth.” The general-in-chief effectively proved that the supplies had been shipped to the army.

President Lincoln’s role remains elusive. Even if not directly involved, he at least exhibits a kind of quiet complicity, if not outright duplicity. His comments to Illinois Senator Orville H. Browning support this claim. Browning noted in his diary that Lincoln confided to him, “He [McClellan] did not follow up his advantages after Antietam.” The president next complained that he had, “coaxed, urged & ordered him but all would not do.” Despite Lincoln’s firsthand observations of the army’s condition and Scott’s discovery of Stanton’s deceitfulness, Lincoln told Browning that McClellan’s greatest defect was, “his excess of caution…he was too slow.”

That refrain of Lincoln’s has been passed down through numerous accounts of McClellan’s career, damning him to the reputation of a commander afraid to wage war. Numerous histories contend that this supply crisis did not exist, and that everything McClellan asked for was supplied, or ignore the issue altogether. The same literature insists that McClellan’s hesitancy to advance after the Battle of Antietam was in consequence of chronic indecision and timidity.

“McClellan’s post-Antietam delay is explainable on military grounds,” wrote noted Lincoln scholar James G. Randall, one of the few who ignored the static and saw the truth. “The delay had resulted from what had been done at Washington over McClellan’s head.” Most likely the true nature of the controversy will never be settled among armchair generals. It cannot be disputed that innocent soldiers suffered in the fall of 1862 as a result of a genuine supply shortage, and that the same shortage frustrated their able commander.

Steven R. Stotelmyer, a native of Hagerstown, Md., first visited Antietam National Battlefield as a child and has been fascinated with the Maryland Campaign ever since. He is a Battlefield Ambassador Volunteer at Antietam and a National Park Service Certified Antietam and South Mountain Tour Guide. This article is culled from his 2019 book, Too Useful to Sacrifice: Reconsidering George B. McClellan’s Generalship in the Maryland Campaign From South Mountain to Antietam (Savas Beatie).

An Army In Name Only

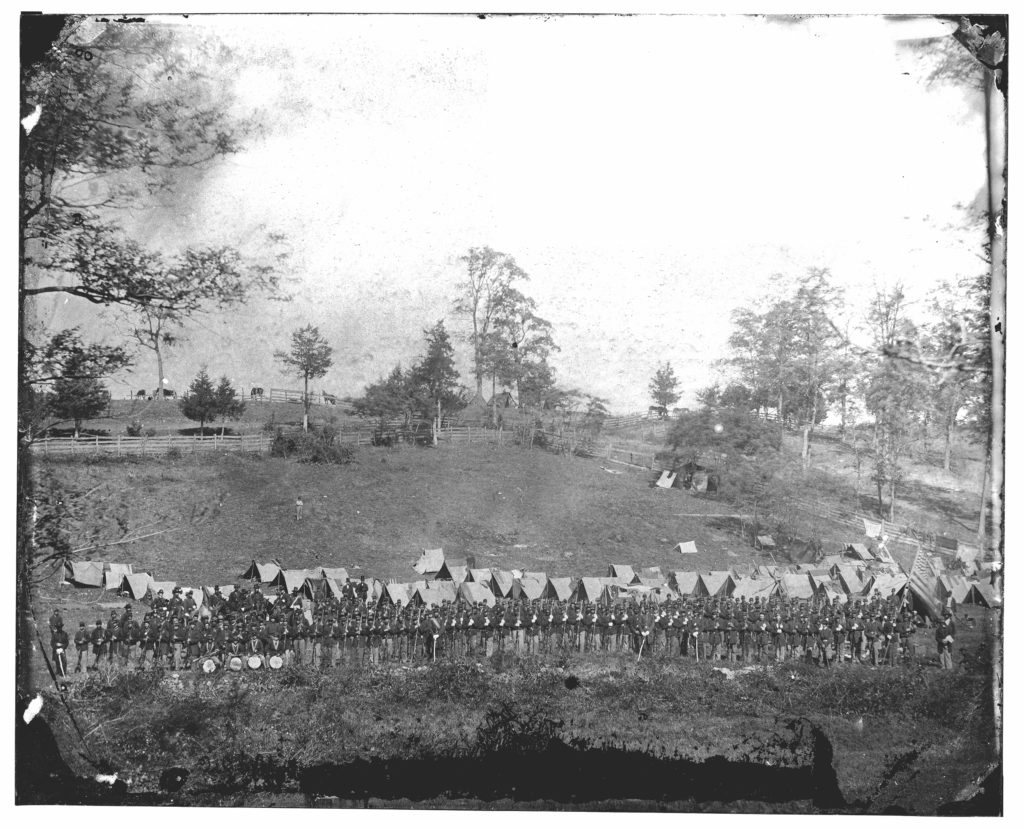

A look at the condition of the Union force during the Maryland Campaign provides a picture of the Army of the Potomac at odds with the generally accepted stereotype of the well-equipped and well-oiled machine of legend. The troops that McClellan began moving out of Washington in early September 1862 belonged to the “Army of the Potomac” in name only. The army was a recently assembled conglomerate.

Troops from Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run composed approximately 30 percent of McClellan’s force. Some of these soldiers were shoeless and without a change of clothing when the Maryland Campaign began. Some of this army consisted of troops McClellan commanded on the Peninsula who did not make it in time to join Pope at Second Bull Run. Major General Ambrose Burnside’s newly expanded 9th Corps had also recently been integrated into the Army of the Potomac. And, approximately 25 percent of McClellan’s troops were new recruits, a fact often ignored when discussing the Maryland Campaign and its aftermath. Although some of the untested regiments had served in garrisons, the urgency of the situation in fall 1862 rushed many green units to the front without proper training.

The condition of the Federal army only worsened after the Battles of South Mountain, Antietam, and Shepherdstown. McClellan expected to have time to rest, refit, and reorganize his army upon the conclusion of the campaign, and time for his fresh regiments to continue their training. The experience of the famous 20th Maine is representative of that. The regiment underwent seemingly endless marching and drill so that by the end of October, Lt. Col. Joshua L. Chamberlain boasted to his wife, “no other New Regt. Will ever have the discipline we have now.” Modern “boot camps” range from between 8 to 12 weeks, however, which means that the Maine men would have had to train to until between mid-November or December to be fully ready. But that was far too late in the season for an impatient President Lincoln.

This story appeared in the June 2020 issue of Civil War Times.