Antonio López de Santa Anna is back in the news 181 years after the Texas Revolution. A recent front page story in the Wall Street Journal and a biting, if somewhat tongue-in-cheek, editorial in the Chicago Tribune reminded Americans there was more to remember about the infamous Mexican general than just the Alamo.

At issue is an impressive wood, cork and leather prosthetic Illinois volunteers captured on the battlefield at Cerro Gordo in 1847. They returned home in triumph from the Mexican War—despite the fact their Whig congressman, Abraham Lincoln, had vehemently opposed the conflict—with Santa Anna’s artificial leg as a trophy.

The detached limb eventually found its way into the Illinois State Military Museum in Springfield. The San Jacinto Battle Monument and Museum in La Porte, Texas, just east of Houston, attempted to dislodge the artifact from Illinois a few years ago without success.

Well-Intentioned Delegation

More recently a small delegation of history students from St. Mary’s University in San Antonio made a pilgrimage to Springfield to press the keepers of the leg to give it up. The students hoped to improve relations with Mexico by restoring the legendary limb to its homeland. The Illinois museum folks gave the young Texans a frosty reception, ironically similar to the response from Mexican museum authorities, who have a rather jaundiced view of Santa Anna.

“While we appreciate the gesture,” said Antonio Saborit, director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico City, “[the museum] must stay at the margins of this complaint, in as much as relics like this are not part of its purview.” The Illinois museum is holding on to its war prize. “We paid for that leg with Illinois blood,” declared a spokesperson.

“At San Jacinto Santa Anna still had the legs he was born with,” editorialized the Chicago Tribune in support of the Illinois claim. “Texans didn’t inflict the injury that necessitated the replacement, and Texans didn’t capture it or preserve it for 169 years.” The Tribune editorial writer did suggest a compromise—the leg could go to Texas “any time it wants to walk there.”

‘Napoléon of the West’

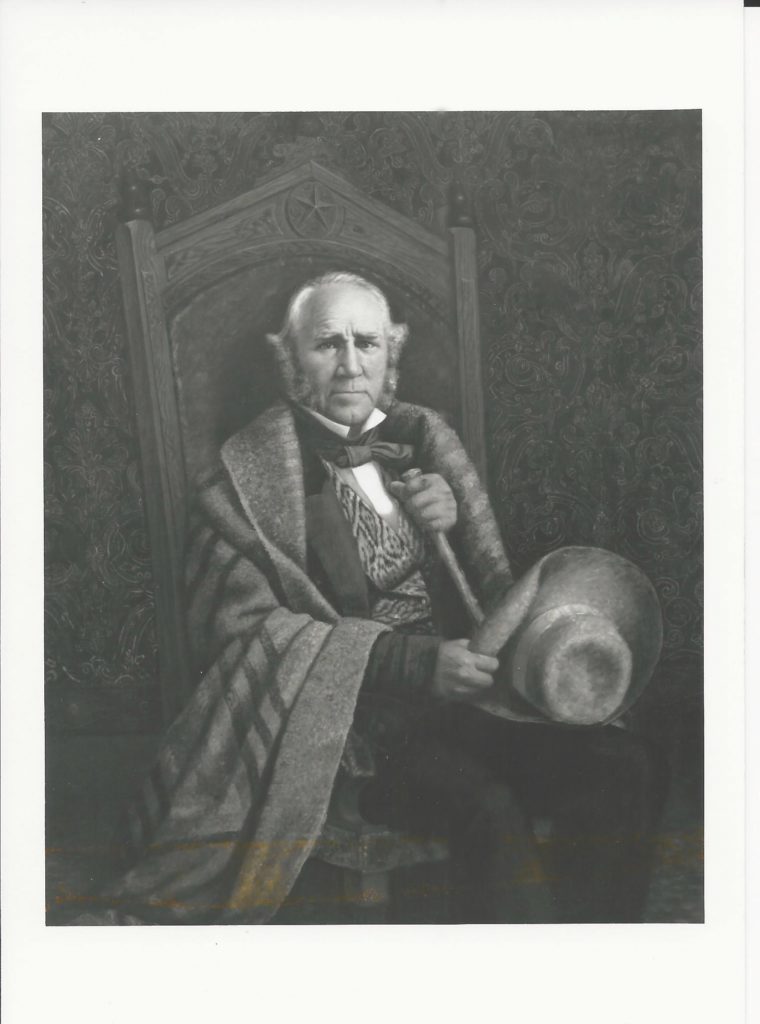

The onetime owner of the disputed appendage was born Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón in the city of Jalapa, Veracruz, on Feb. 21, 1794. His family was of modest means but, more important, of Spanish descent (a group referred to as Creoles in Mexico). He matured into a handsome, charismatic young man of 5 feet 10 inches.

Even before his commission as a gentleman cadet, a title of distinction, into the Fixed Infantry Regiment of Veracruz in 1810 he had become enamored with the military career of French Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte. He modeled himself after his idol and in years to come adopted the moniker “Napoléon of the West.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

This Mexican Bonaparte was soon in the thick of Indian fighting in provinces bordering the Gulf of Mexico, where he received an arrow wound, and then in 1813 against freebooters in Texas, where he was cited for gallantry.

In addition to Napoléon, gambling and women were the young officer’s other obsessions, and in 1814 he was caught forging senior officers’ signatures and pilfering regimental funds to repay gambling debts. His natural charm, as well as friends in high places, saved his career, but the scandal dogged him after he transferred to the Second Battalion of Grenadiers in Veracruz.

Recommended for you

Effective Royalist Officer

He secured another award for bravery in the desultory campaigns that ran to ground the last remnants of Father Miguel Hidalgo’s abortive revolt against Spanish rule.

By 1820 Santa Anna had proven among the most effective of the royalist officers in combat against the insurgents. But with the rise to power of a new liberal Spanish government and constitution that threatened the status of the Catholic church and the colonial elites, a more conservative set of Mexican rebels rose under royalist Colonel Agustín de Iturbide.

Iturbide had once been Santa Anna’s commander, and in 1821 the young officer switched sides—even as Spanish authorities were processing his promotion to lieutenant colonel. The popular Santa Anna took 600 soldiers with him. Iturbide rewarded him with a promotion to general and command of the vital port of Veracruz, with its lucrative customs house.

In May 1822 Iturbide proclaimed himself emperor of Mexico, a victory for conservatives over the longtime revolutionaries. But he soon began to fret over his ambitious commander in Veracruz. Relieving Santa Anna of command, Iturbide ordered him to report to Mexico City. The young general instead joined rebel forces.

“So rude a blow wounded my military pride and tore the bandage from my eyes,” Santa Anna recalled. “I beheld absolutism in all its power.”

Joining Liberal Insurgents

On Dec. 6, 1822, Santa Anna proclaimed for a Republic of Mexico from his Veracruz headquarters. Joining with liberal insurgents, he endorsed the Plan of Casa Mata, which called for the overthrow of Iturbide and the establishment of a congress and a federal republic.

Years later Santa Anna would confess that in 1822 he did not actually know what a republic was. Iturbide abdicated in 1823 and went into self-exile in Europe. A year later, after receiving word of a Spanish plan to reconquer Mexico, he foolishly returned. The presumptuous ex-emperor was promptly arrested and executed by firing squad on July 19, 1824.

Romance temporarily distracted young Santa Anna from politics when he married 14-year-old Doña Inés de la Paz García on March 16, 1825. She was of Spanish descent and brought a moderate dowry with her. In time she bore Santa Anna two daughters and two sons and proved a devoted mother who avoided the limelight. Sadly, her 31-year-old husband continued with his womanizing, while lavishing more attention on his ever-growing collection of Napoléonic artifacts.

He also gambled incessantly and soon had a roostful of plucky gamecocks. Doña Inés retreated into the background, often separated from her dashing husband, until her premature death at age 35 on Aug. 23, 1844. Within weeks the 50-year-old widower married María Dolores de Tosta, a 15-year-old beauty of good family but headstrong disposition. It was not a happy union.

Marching on Mexico City

In October 1824 Guadalupe Victoria was elected first president of the republic of Mexico under the constitution of 1824 (modeled on that of the United States). Santa Anna provided crucial support, and Victoria became the only Mexican president before the 1860s to serve a full four-year term.

The expiration of Victoria’s term ended Santa Anna’s support for the republic, for in 1829 he helped overturn the election and installed the losing candidate, the popular old revolutionary Vicente Guerrero, as president. He received promotion to the rank of general of division (the highest rank in the army) as his reward. The new general promptly proved his worth at Tampico in September 1829 when he defeated a Spanish invasion force from Cuba.

While Santa Anna faced down this foreign threat, intrigue ruled in Mexico City. Vice President Anastasio Bustamante deposed Guerrero and promptly had him executed, throwing the government into chaos. It was a moment made for Santa Anna. Acting on his Napoléonic instincts, he marched on Mexico City, overthrew the illegitimate government and restored order.

As the undisputed hero of the hour, Santa Anna easily won election as president in 1833 as a liberal committed to the federal constitution of 1824. He declined to take an active role in politics, leaving the details of government to his vice president, Valentín Gómez Farías, while he retired to his vast estate in Veracruz.

Becoming a Dictator

In his absence Farías unwisely sought to undermine the power of both the army and the Catholic Church. The generals, who supported the church and a centralized government, rebelled and called on Santa Anna to assume the role of dictator. Once again the young general marched on the capital to restore order.

He at first denounced the conservative generals, but then suddenly turned on his own vice president. Farías had called out the state militias in support of federalism, and this proved his undoing. In 1835 Santa Anna deposed his vice president, dissolved the congress, repealed the constitution of 1824, dismissed state legislatures and declared himself dictator.

Federalist militias in five states rose against Santa Anna, but the army and the church rallied to him, and he quickly defeated his enemies. Resistance in the north-central state of Zacatecas was particularly strong. Determined to make an example of the liberal rebels, Santa Anna executed their leaders and unleashed his army to engage in savage reprisals against the civilian population. By 1835 the only remaining federalist stronghold was north of Coahuila in the department known as Texas.

Banning Immigration from the U.S.

Texas had long been troublesome to both Spain and Mexico. In 1821 there were fewer than 3,000 settlers in Texas. Continually harassed by the Comanches, they lived precarious lives distant from any markets for their produce or cattle. In 1825 the Mexican government offered large land grants and favorable tariff and tax incentives to encourage foreign colonists to settle in Texas.

They hoped the colonists might blunt the Comanche raids that had plagued the other northern Mexican states, as well as breathe some economic life into the beleaguered province. Among the most prominent of empresarios (“entrepreneurs”) who brought colonists into Texas was Stephen F. Austin.

These new settlers were required to swear allegiance to the republic, convert to Catholicism and know or learn Spanish but were otherwise left alone by Mexico City. By 1830 these colonists, almost all of them Americans, outnumbered the Hispanics in Texas 10-to-1 and were increasingly restless under Mexican rule. All their trade, mostly in cotton, went east to the United States. They flagrantly ignored the Mexican law against slavery and were openly contemptuous of the Catholic faith.

The government in Mexico City responded with a new set of laws in 1830 that banned further immigration from the United States, ended tariff exemptions and reinforced the ban on slavery. The outraged citizens of Texas—Anglos and wealthy Hispanics alike—banded together to protest the legislation. Many supported Santa Anna in his 1833 election as president.

No Friend to Texas

Santa Anna proved no friend to Texas, and in August 1835 he sent his brother-in-law, Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cos, to Texas with 500 troops. Cos soon announced his intention to drive all Americans who had been in Texas fewer than five years out of the province. But when Cos sent troops to Gonzales in October to confiscate the small cannon they used to deter Comanche raids, the Texians fired on the Mexican soldiers, sparking the Texas Revolution.

Austin soon led a disorganized but effective militia force against Cos at San Antonio de Béxar, the largest town in Texas, and on December 10 the Mexicans surrendered. Cos and his men were paroled and, after promising never again to take up arms against Texas, allowed to march south in peace.

This humiliation stained not only Mexican military honor but also Santa Anna’s family name. Adding insult to injury, his longtime political ally, Lorenzo de Zavala, had resigned his position as minister to France to return to his estate in east Texas and join the rebel cause. At a Mexico City dinner with the French ambassador Santa Anna boasted, “If the Americans do not behave themselves, I will march across their country and plant the Mexican flag in Washington.”

Taking the field personally, Santa Anna advanced to Saltillo where he organized several thousand men into a poorly equipped army that then endured a grueling march to the Rio Grande dogged by disease, no medical care, poor rations and brutal weather. The commander ordered Cos and his troops to violate their parole and join the invasion force.

Captives to be Executed

Santa Anna proclaimed that any foreigners captured under arms were to be considered pirates and thus marked for summary execution. After the campaign’s successful conclusion he expected all foreigners to be expelled from Texas, their land grants nullified, their slaves freed.

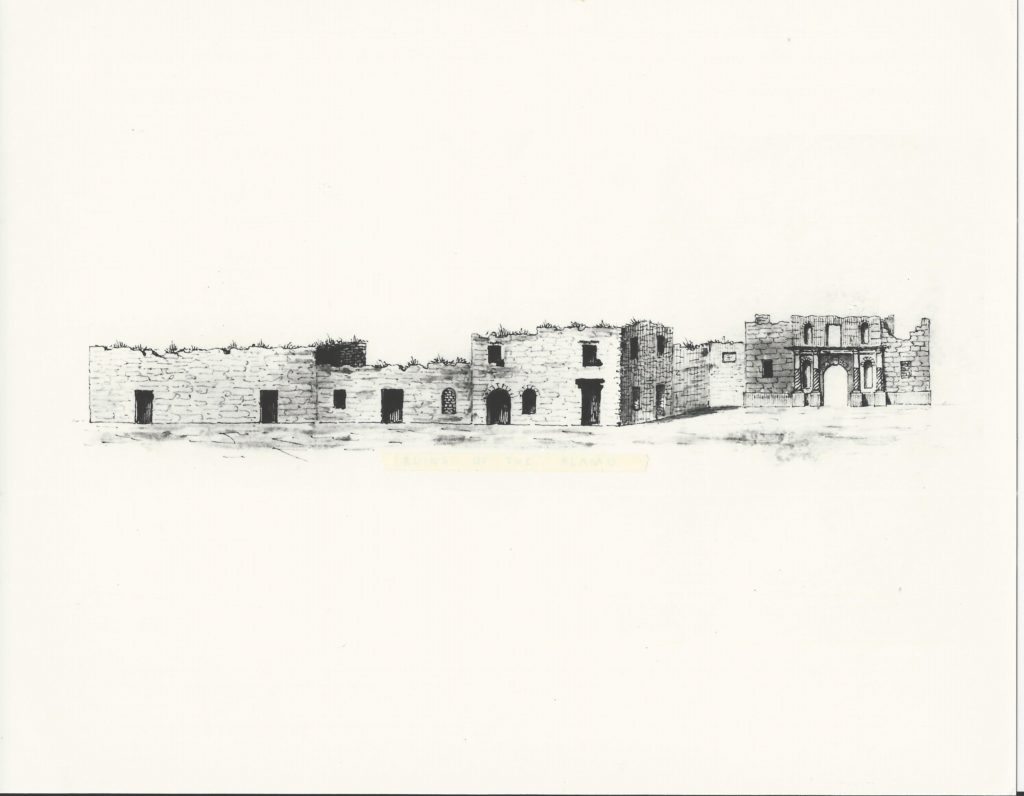

On Feb. 21, 1836, Santa Anna’s 42nd birthday, he was at the head of his army some 25 miles from San Antonio. In hopes of surprising the Texians, the commander ordered General Joaquín Ramírez y Sesma on a surprise attack with an advance guard of lancers of the Dolores Regiment. A rainstorm delayed the lancers, giving the Texians time to retreat into a fortified old mission on the edge of town called the Alamo.

Sam Houston, commander of the rebel army, had sent friend Colonel James Bowie to the Alamo with orders to remove the artillery, destroy the sprawling fortifications and retreat eastward. Bowie disobeyed the order, declaring in a letter to provisional Governor Henry Smith, “We will rather die in these ditches than give them up to the enemy.”

Bowie, a living legend on the frontier who had given his name to a man-killing blade, soon fell ill, leaving effective command of the Alamo to 26-year-old cavalry officer Lt. Col. William Barret Travis. Joining his force of fewer than 200 men was a band of Tennessee volunteers under former U.S. congressman David Crockett, a celebrated figure of international renown.

Short but Bloody Battle

Enrique Esparza, 8 years old at the time, remembered well the grand entry of Santa Anna into San Antonio. “Riding in front was Santa Anna, el Presidente!” he recalled years later. “This man was every inch a leader. All the officers dismounted, but only the general tossed his reins to an aide with a flourish. I was very impressed.” The boy then fled with his family into the doubtful sanctuary of the Alamo.

For 13 days Santa Anna besieged the Alamo. Finally, on March 4, 1836, he called his officers together for a war council. In the contentious meeting General Manuel Fernández Castrillón argued that any assault should be postponed until heavier artillery arrived. He then joined with Colonel Juan Nepomuceno Almonte to protest the red flag declaration that no quarter would be given the rebels. The general dismissed his officers’ protests and ordered them to prepare for a predawn assault on March 6.

More than 1,000 troops took part, hitting the fortress from all sides: Cos from the northwest with 350 men; Colonel Francisco Duque from the northeast with 350; Colonel José María Romero from the east with 300 soldiers; and Colonel Juan Morales from the south with 100 men; while General Sesma’s cavalry patrolled the perimeter to prevent the escape of any defenders.

The battle was short but bloody, the attacking columns suffering heavy casualties. At the outset Colonel Duque fell wounded, and his soldiers faltered. Castrillón quickly took command of Duque’s column as Santa Anna committed his 400 reserves to the assault. It was all over within two hours.

Two Silver Dollars and a Blanket

Santa Anna entered the fort at 6:30 am. Lieutenant José Enrique de la Peña, an aide to Colonel Duque, recalled the scene in his memoirs, published in 1955. The journal, whose validity few historians debate, offers a compelling account of the battle aftermath. As he commended the assembled troops on their glorious victory, Castrillón approached with five bloodied prisoners.

De la Peña was fascinated by one of these men—“one of great stature, well proportioned, with regular features, in whose face there was the imprint of adversity, but in whom one also noticed a degree of resignation and nobility that did him honor.” The lieutenant later learned the man “was the naturalist David Crockett, well known in North America for his unusual adventures.”

Santa Anna was furious with Castrillón for disobeying his orders and demanded he immediately execute the men. When Castrillón demurred, the officers of Santa Anna’s staff fell upon the defenseless prisoners with their sabers.

Santa Anna later met with the handful of noncombatant survivors of the battle—Susannah Dickinson and her infant daughter, Angelina, and Ana Esparza and her four children, as well as Travis’ slave Joe and a half-dozen Tejano women. Santa Anna gave each of the widows two silver dollars and a blanket.

A Hard and Cruel Look

“He had a hard and cruel look, and his countenance was a very sinister one,” widow Esparza’s young son Enrique later recalled of being in the presence of the man responsible for his father’s death. “It has haunted me ever since I last saw it, and I will never forget the face or figure of Santa Anna.”

Despite the butcher’s bill of as many as 600 Mexican dead or wounded, including 26 officers killed, Santa Anna was well pleased. “Much blood has been shed, but the battle is over,” he sniffed to staff officer Colonel Fernando Urriza. “It was but a small affair.” In a journal entry following the battle Captain José Juan Sanchez, adjutant to Cos, lamented, “With another victory like this one, we may all end up in hell.”

Santa Anna tarried several weeks in San Antonio, reportedly in pursuit of a local beauty. In the meantime General José Urrea’s column overtook a retreating Texian force from Goliad and forced their surrender. Urrea had the men imprisoned in Goliad and moved on, leaving a colonel in command. He then wrote Santa Anna to seek clemency for the Texians.

Infuriated, the commander sternly rebuked his general, then sent his standing order to execute all rebels directly to Urrea’s deputy at Goliad. On March 27 the Mexican captors marched 342 Texian prisoners from town and murdered them along the roadside. A handful escaped in the confusion to carry the tale of Santa Anna’s perfidy to the world.

Santa Anna Sent as a Prisoner

In early April Santa Anna, finally back in pursuit of the rebel army with 1,100 men, soon outdistanced the supporting columns under Generals Urrea, Vicente Filisola and Antonio Gaona, burning Texas towns as he advanced. He was soon reinforced by Cos with 400 men.

By April 20 he believed he had trapped Houston’s 800-man force near the coast on the San Jacinto River. But around 4:30 p.m. on April 21 it was Houston and his ragtag force that sprang the trap on Santa Anna, who had grown complacent and contemptuous of his foe. The Mexican commander fled the field, while the Texians killed 600 of his men and captured another 730.

The next day a search party captured Santa Anna and brought him before Houston. In exchange for his life the vanquished general agreed to order all Mexican troops out of Texas and to urge his government to recognize Texas’ independence. After letting Santa Anna linger in prison for seven months, Houston sent him east to Washington to meet with President Andrew Jackson.

An American warship carried Santa Anna back to Veracruz where, incredibly, he was greeted as a hero. He retired to his estate but was soon called back into military service to meet a French invasion force in a brief 1838 conflict over debt and trade agreements dubbed the Pastry War. In the thick of battle grapeshot shattered Santa Anna’s left leg.

Carried on a Litter as a Hero

A field surgeon amputated the leg below the knee, and his men carried their wounded hero in triumph back to Mexico City on a litter, where—despite Santa Anna’s capitulation to French demands—Congress for the fifth time named him president.

In the years that followed the continued bitter partisan politics between liberals and conservatives allowed the scheming general to move repeatedly in and out of power. The government called him back from self-exile in Cuba to meet the American invasion in 1846, but he soon lost battles in the north to General Zachary Taylor and in the south to General Winfield Scott.

At Cerro Gordo, east of Mexico City, on April 18, 1847, Santa Anna lost the decisive battle of the Mexican War, as well as his cork leg when his baggage was captured. He again fled into self-exile, this time to Jamaica, as others made peace with the conquerors with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildalgo, which ceded one-third of Mexico’s northern territory.

Santa Anna returned to power for the 11th, and final, time in April 1853. During his term he negotiated the Gadsden Purchase with the United States for $10 million. He squandered much of the money and would have sold even more land had the Americans come up with the money.

Forced into Exile

Liberal opponents finally forced him into exile again in 1855 and thus saved Mexico from the loss of further territory. Not until 1874 was Santa Anna granted amnesty and finally allowed to return from exile. The Napoléon of the West died impoverished, nearly blind and largely forgotten on June 21, 1876—four days before the death of another controversial Western commander up north along Montana Territory’s Little Bighorn River.

In the United States today, when Santa Anna is remembered at all, it is as the villain of the Battle of the Alamo, yet his tempestuous career left an indelible mark on the history of the sister republics to the north and south of the Rio Grande. And his artificial limb remains enshrined in the military history of Illinois.

This story originally appeared in the February 2018 print edition of Wild West.

Paul Andrew Hutton, distinguished professor of history at the University of New Mexico, is an award-winning author and frequent contributor to Wild West. For further reading he recommends “Santa Anna: A Curse Upon Mexico,” by Robert L. Scheina.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.