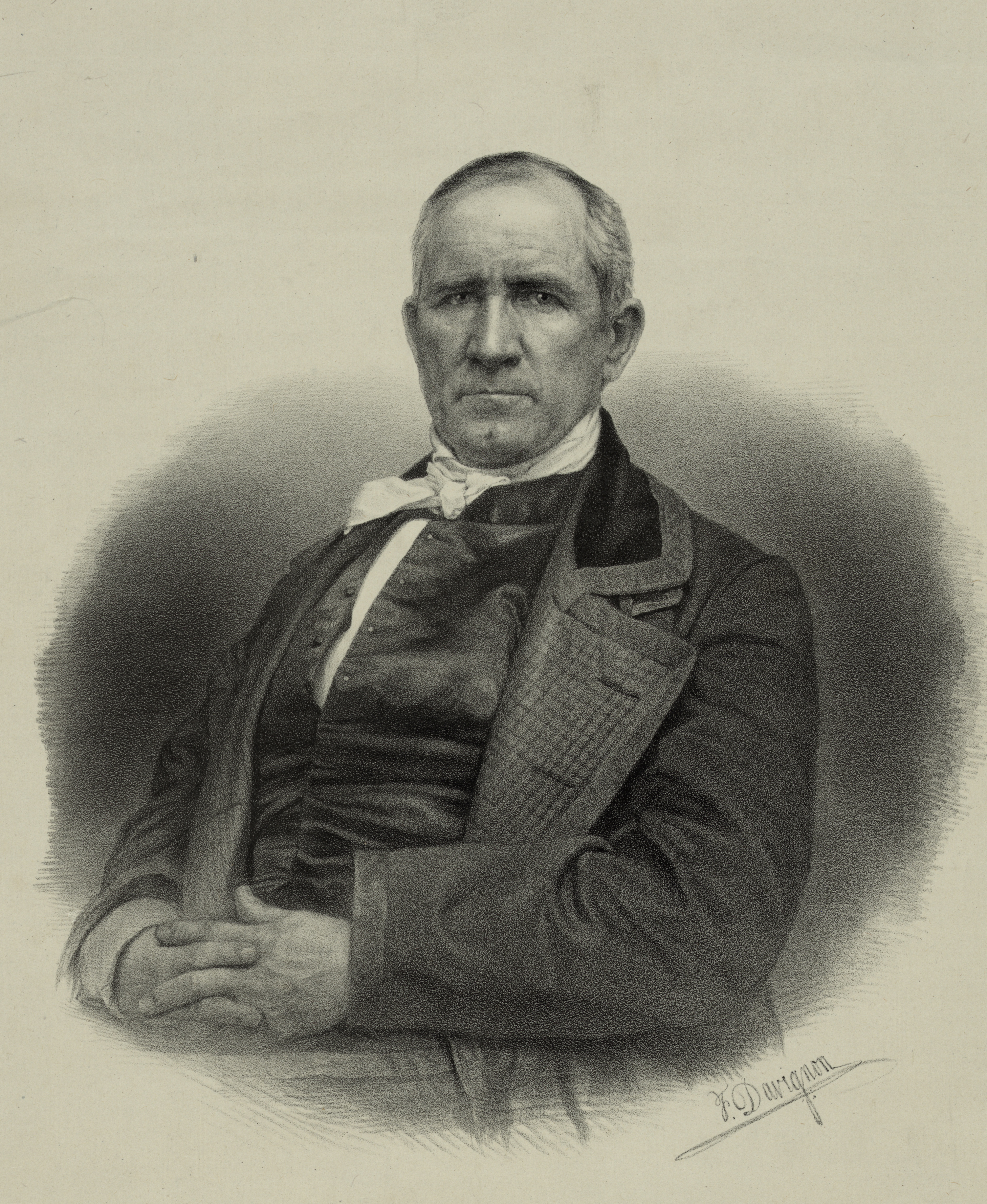

Victory at San Jacinto secured independence from Mexico and made him a hero, but he faced countless trials and tribulations—before and after.

Inside what many considered the ugliest house in the state of Texas, Sam Houston lay dying. Not in his bedroom, though. In midsummer the upstairs of the “Steamboat House” in Huntsville felt like a furnace, so Houston had been resting on a couch on the first floor of his rented home.

For such a robust outdoorsman, Houston had never been blessed with excellent health. Old wounds had failed to heal completely, and now Houston’s former slave, Jeff Hamilton, remained at the deposed Texas governor’s side, administering medicine, fanning away flies and changing the bandages on those old injuries, including one abscessed wound that bled as it had when inflicted in 1814.

The date was July 26, 1863.

Houston’s wife of 23 years—the former Margaret Moffette Lea of Marion, Ala.—had rarely left her husband’s side since he had come home. The 70-year-old Houston had spent four weeks at the Sour Lake mineral springs in east Texas, hoping to revitalize his failing health. Returning to Huntsville on July 8, he paid a courtesy visit to Union prisoners of war in the Texas State Penitentiary and then went home, knowing he would never again leave the house alive.

Margaret and all the Houston children—except Sam Jr., a Confederate soldier who had been wounded at Shiloh and later furloughed and was traveling in Mexico with an uncle (likely a plot Houston had hatched to keep his eldest son from further harm)—gathered by his side for the end. The children sobbed. Houston had been drifting in and out of consciousness, but as Margaret read from the Bible he stirred.

“Texas!” he cried, naming the state—once a republic—he had helped forge. “Texas!”

Margaret held her husband’s hand.

His last word was a name he loved even more than Texas: “Margaret.”

At 6:15 p.m. Sam Houston died.

Margaret gently removed a ring from the pinkie on her husband’s left hand. His mother, Elizabeth Paxton Houston, had given her son the ring when he had joined the U.S. Army during the War of 1812. Sam’s father had been an officer during the Revolutionary War, and the prospects of soldiering had also seemed better to Sam than teaching school in Maryville, Tenn. But in March 1813 Houston had been only 20 years old and required his mother’s consent—his father having died in 1806—to enlist. She had granted her permission, slipped the ring onto his finger and, if family lore is true, even gave him a musket. It was fitting Houston wore that ring until his death. The thin gold band had defined his life.

Samuel “Sam” Houston was born on March 2, 1793, the fifth of nine children, in a cabin just north of Lexington in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. The el- der Samuel Houston, a militia inspector, was a poor money manager and faced massive debts (a trait his son seemingly inherited). In late 1806 he decided to sell the family property and start fresh in Tennessee, where some of his kin had settled. Yet before the family could move, Houston died unexpectedly. After settling the debts, Elizabeth Houston moved her children in the spring of 1807 to the farm her husband had bought near Maryville, Tenn.

Along Bakers Creek the widow and her children cleared land, built a home and turned to farming. Unlike her late husband Elizabeth Houston had a sound business mind and soon invested in a Maryville store. Two of Sam’s brothers, James and John, pitched in to help, but young Sam was not taken to the hoe or ax or clerking in a mercantile. He did love to read— Homer, Virgil, history and geography—but, although enrolled in the newly chartered Porter Academy, he did not take to school, either.

Already big for his age—he stood just under 6 feet tall as a young teen when the family left Virginia—Houston loved the woods and had an almost insatiable curiosity. The family farm lay practically spitting distance from the Cherokee Nation, and the youngster enjoyed meetings with those Indians.

It surprised no one when around 1809 Houston ran away from home to join a band of Cherokees on a Hiwassee River island. The leader of the village, Oolooteka (known to whites as John Jolly), liked the strapping teenager, adopted him and gave him the name Colonneh, which meant “the Raven.” Houston would visit family from time to time—perhaps to talk his mother out of a little cash—but for the next three years Houston lived with the Cherokees. Those years gave him an Indian perspective that in years to come would bring him honor among the Indians while baffling and irritating many whites.

In 1812 Houston returned to Maryville and soon announced he would teach school—news that must have flattened his old schoolmaster, fellow students and family. Charging tuition of $8 a term, he began his new pursuit in a log cabin in Maryville, eating lunch with his students, whittling and wearing “a hunting shirt of flowered calico, a long queue down my back.” To deal with any students of the sort he had been, Houston also packed a set of lead knuckles. (Not that he needed such a weapon, as he stood at least 6-foot-2; some reports have him as tall as 6-foot-6, but family sources say otherwise.)

To most everyone’s surprise Houston’s school proved successful, and he managed to pay off his debts. But prosperity didn’t last long. It seldom would. By March 1813 he was again lamenting his financial situation when wanderlust struck again. The Army began recruiting in Maryville for America’s second war against Britain, offering a silver dollar as a signing bonus, and Houston, with his mother’s help, joined. He had enlisted as a private in the 39th Infantry, but before that first day was over he was a sergeant.

A lieutenant colonel in his regiment soon noticed Houston’s abilities, calling him “frank, generous, brave…and always prompt to answer the call.” That officer was Thomas Hart Benton, who in his postwar career as a Missouri state senator (1821–51) would champion the United States’ westward expansion and Manifest Destiny. Having Benton as his champion must have benefited Houston, as within the year he was promoted to ensign and then third lieutenant. In February 1814 the 39th joined forces with another army, and Houston first met the man who would mentor and support him and be another father figure.

Houston reportedly later said of Andrew Jackson, “Whether his policy was right or wrong, he built up the glory of the nation.” So would Houston.

While the War of 1812 pitted the United States against Britain, Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson’s army initially pursued Creek Indians. Having united tribes in Ohio and surrounding territories in an effort to drive out American settlers, Shawnee leader Tecumseh had traveled southeast in 1811 and successfully persuaded many Creeks to fight the Americans. In late 1813, after months of bitter fighting, Jackson had marched south with a force of Army Regulars, Tennessee militiamen, Cherokee Indians and Creek allies.

By spring 1814 roughly 1,000 Red Stick Creeks had retreated to east-central Alabama, near the confluence of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers, erecting log breastworks at a curve in the Tallapoosa called Horseshoe Bend. There they waited for Jackson. And early on March 27, 1814, he attacked. “Arrows and spears and balls were flying,” Houston recalled. “Swords and tomahawks were gleaming in the sun.” But any visions he may have held of the glory of war quickly faded. Horseshoe Bend, so serene today, became one of the ugliest scenes of the war. “Not a warrior offered to surrender,” Houston said, “even while the sword was at his breast.”

Waving his sword, Houston led his platoon over the breastworks, where the fighting was hand to hand. As soldiers fell around him, a barbed arrow struck Houston in the groin. He refused to quit, and after the Creeks retreated from the breastworks, he ordered a reluctant officer to yank free the arrow. The arrow came out but left a gash that spouted blood, forcing Houston to find a surgeon the stanch the flow. Riding past the wounded, General Jackson queried the injured lieutenant and ordered him to remain behind the lines, but Houston didn’t listen to his commander. Late in the battle, when Jackson called for volunteers to storm the sturdy log-roofed redoubt that housed most of the surviving Creeks, Houston grabbed a musket and called for volunteers to follow him. Fifteen feet from the redoubt, musket balls slammed into Houston’s right arm and shoulder. He called on his men to charge with him, but realizing he stood alone, he stumbled back up the ravine and collapsed.

Jackson ordered the redoubt burned. Payback, perhaps. In August 1813 Creeks had stormed Fort Mims in Baldwin County, Ala., killed most of the defenders and torched the stockade and buildings, burning alive a number of settlers, including women and children. “The sun was going down, and it set on the ruin of the Creek Nation,” Houston wrote of Horseshoe Bend. “Where but a few hours before a thousand brave warriors had scowled on death and their assailants, there was nothing to be seen but volumes of dense smoke rising heavily over the corpses of painted warriors and the burning ruins of their fortifications.” Jackson’s men had killed at least 800 Creeks, while his own losses were reported at 49 killed and 154 wounded.

In August 1814 the Creeks signed a treaty with Jackson, resulting in a massive land grab for the United States. The Horseshoe Bend fight, coupled with Jackson’s subsequent victory over the British at New Orleans, would help propel Jackson to the White House.

Houston’s war, for all intents and purposes, was over after Horseshoe Bend, but he had made an impression on “Old Hickory.” And the war had made a lasting impression on Houston.

Nearly five decades later, in speeches to Texans champing for secession and Civil War, he would caution against “a leap in the dark—a leap into an abyss, whose horrors would even fright the mad spirits of disunion who tempt you on,” warning them the Union would sink the Confederacy “in fire and rivers of blood,” and “your fathers and husbands, your sons and brothers, will be herded together like sheep and cattle at the point of the bayonet, and your mothers and wives, your sisters and daughters, will ask, ‘Where are they?’ and echo will answer, ‘Where?’” He did everything within his power to keep Sam Jr. out of the fighting.

Houston returned home to recuperate after Horseshoe Bend. Doctors in Knoxville, New Orleans and New York sought to mend his wounds, but they would plague him the rest of his days. By May 1815 he had rejoined his regiment and been promoted to second lieutenant. He made first lieutenant in 1817, and by that autumn he was serving, at the request of Jackson and Cherokee agent Return J. Meigs, as sub-agent for the Hiwassee Cherokees.

In February 1818 Houston traveled to Washington with a Cherokee delegation to meet with Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and President James Monroe. In 1816 Jackson and other officials had brokered a treaty—signed by Cherokee leaders who lacked the authority to speak for all Cherokees— in which the tribe was to cede its Tennessee lands in exchange for territory west of the Mississippi River. Houston was tasked with keeping the peace by persuading the Cherokees to leave without a war. He did his job, but when he showed up in Calhoun’s office dressed in Cherokee regalia, he incurred the secretary’s wrath. The offended agent soon resigned.

To make ends meet, Houston turned to the law. Six months after reading in Judge James Trimble’s office in Nashville, he passed the bar and began practicing in nearby Lebanon. In his new capacity Houston often hobnobbed with men of influence, including Jackson and Tennessee Governor Joseph McMinn. Within months of Houston’s arrival in Lebanon, McMinn had appointed him adjutant general of Tennessee.

He rose quickly in Tennessee politics: elected attorney general of the Nashville district in 1819, major general of the state militia in 1821 and U.S. Representative in 1823 and 1825. In 1827 Houston was elected Tennessee governor, and when Jackson was elected president the following year, Houston’s political future seemed assured.

Then came a scandal historians have never quite solved. On January 22, 1829, Houston married 19-year-old Eliza Allen of Gallatin, Tenn. The marriage seemed doomed from the start. One woman recalled that while Houston was embroiled in a snowball fight shortly after the wedding, his new bride remarked in earnest, “I wish they would kill him.” Houston, others said, seemed brokenhearted.

By early April, Eliza had left him. The reasons remain unclear. Neither Eliza nor Houston, who formally filed for divorce in 1833, spoke publicly on the separation. On April 16, 1829, Houston resigned as Tennessee’s governor and went into self-exile in Arkansas Territory, joining his Cherokee friends who had been kicked out of Tennessee. “He let his hair grow and braided it in a long queue, which hung down his back, and wore his beard upon his chin in a ‘goatee,’ shaving the rest of his face,” wrote Houston biographer Alfred M. Williams in an 1883 magazine article.

Rejoining Oolooteka, Houston thrived with the Cherokees. He became a Cherokee citizen and took a mixed-blood Cherokee wife, Tiana, with whom he ran a trading post called Wigwam Neosho near Cantonment Gibson (designated Fort Gibson in 1832), in what would later become Oklahoma. He defended Indians in a series of articles for The Arkansas Gazette and went to bat for his wife’s brother after the latter had been fired as a Cherokee interpreter. He also drank. A lot. So much the Cherokees called him “Big Drunk.”

Yet Houston had not completely rejected white society. He kept in touch with Jackson and represented the Cherokee Nation—once again donned in traditional Cherokee clothes— in Washington. He returned to Bakers Creek in the fall of 1831 to be with his mother when she died. And he showed his pride and his temper.

In 1832 Houston was visiting Washington when he ran into U.S. Rep. William Stanbery of Ohio. That spring on the House floor Stanbery had made veiled allegations of fraud between Houston, as Tennessee governor, and former Secretary of War John Eaton. Confronting the congressman on Pennsylvania Avenue, Houston, with cane in hand, knocked Stanbery to the ground and severely beat him. In the tussle Stanbery pressed a pistol to Houston’s chest and pulled the trigger, but the gun misfired. The case went before the House of Representatives, with Francis Scott Key representing Houston, though Sam himself delivered the closing argument. He was reprimanded, of course, but at the conclusion of his speech the House erupted in a thunderous ovation.

In short, Sam Houston was back. But instead of returning to Tennessee to resurrect his political career, Houston, possibly financed by Jackson (the two met at Jackson’s Nashville home, the Hermitage, on August 18), went to Texas. Both men likely saw an opportunity to annex Texas into the United States.

After settling his affairs with the Cherokees (deeding the trading post and other property to wife Tiana, who would die of pneumonia in 1838), Houston crossed into Texas on December 10, 1832. He was soon practicing law in Nacogdoches. “Now the resident of another government,” Houston wrote to a cousin, “in the finest portion of the globe that has ever blessed my vision.” Houston also found Texas to be the proverbial kettle about to boil over.

Years earlier Mexico had reluctantly allowed American empresarios such as Stephen F. Austin to bring in settlers to colonize the vast region. Texas had been an independent colony until the first Mexican constitution merged Texas and the state of Coahuila. Mexico also eliminated the right to a trial by jury and in 1829 formally abolished slavery. The following year it banned further emigration from the United States. American transplants weren’t happy.

Antonio López de Santa Anna was first elected president of Mexico in 1833, and in 1834 he dissolved Congress, replaced the 1824 constitution and turned the country into a military dictatorship. Almost immediately states rebelled. “Most people don’t realize this was a federalist-centralist conflict,” explains Larry Spasic, president of the San Jacinto Museum of History in La Porte, Texas, “and that the rebellion wasn’t just in Texas. It was originally a fight for the Constitution of 1824. Nobody was fighting for independence.”

That quickly changed. By 1835 Houston had been named commander in chief of the Department of Nacogdoches by the town’s Committee of Vigilance and Safety (he celebrated by buying a new general’s uniform in New Orleans), and on November 12 Texas’ provisional government made him major general of the Texas army.

He kept busy, ordering James Bowie to blow up the old mission known as the Alamo in San Antonio de Béxar and negotiating a treaty between Texas and the regional Cherokee chief known as The Bowl. Nacogdoches declined to elect him as a delegate to the Convention of 1836— he had been its delegate at an 1833 convention—but the coastal town of Refugio did elect him, so Houston rode to Washingtonon-the-Brazos. There the convention convened on March 1, and the following day —Houston’s 43rd birthday—Texas declared its independence from Mexico. On March 4 Houston was appointed major general of the Army of the Republic of Texas, in command of all regular, volunteer and militia troops. That might have been splitting hairs, as Houston had been leading the army for almost four months.

Earlier Houston had said, “Since our military power is weak, let our strength be in our unity.” Yet Texas was hardly united.

Back in 1835 James Fannin, who would face execution along with most of his command at Goliad, had not only wanted to “reduce Matamoros” but also wanted his troops to “be paid out of the first spoils taken from the enemy,” acts Houston likened to piracy. Smarting over prior land deals, the general council had refused to commission Jim Bowie as an officer of the Texas army. Houston had wanted the Alamo destroyed, insisting, “It will be impossible to keep up the station with volunteers.” No one had listened.

The situation had not improved as Santa Anna led troops into Texas to put down the insurrection. Backstabbing and secondguessing became common traits of Texas’ government officials, especially interim President David G. Burnet, though the malaise also spread among Houston’s own soldiers. Houston’s drinking did not help matters. Unity? More like chaos and dysfunction.

Shortly after Houston’s appointment as major general, word reached Washington-on-the Brazos that Santa Anna had surrounded the Alamo, trapping William B. Travis, David Crockett, Bowie and other Texians. Travis pleaded for reinforcements, and representative Robert Potter— who had cast the sole vote against Houston’s appointment as army commander—made a motion that the entire convention march to San Antonio. To Houston that was “madness,” but he did agree to march there with what little army he had. On March 6 he set out— though not especially in a hurry.

Four days later Houston and his ragtag army reached Gonzales, where they learned the Alamo had fallen and all its defenders were dead. On March 27 Fannin and his troops were executed at Goliad. Houston had 374 men, not all were armed and most lacked both experience and discipline. So he ordered a retreat. “By falling back, Texas can rally and defeat any force that can come against her,” he reasoned.

The “Runaway Scrape” had begun. It wasn’t just Houston’s army that was retreating. Settlers also ran for the perceived safety of the Sabine River and the U.S. border. As John M. Swisher, a captain with the army, recalled, “All the country west of the Brazos was depopulated.”

If the withdrawal angered Houston’s men, Burnet was all the more furious. “The enemy are laughing you to scorn,” he wrote. “You must fight them. You must retreat no farther. The country expects you to fight.”

Houston didn’t listen. Heavy rains darkened the mood of his army, which somehow managed to grow in numbers if not in morale, while Santa Anna remained overly confident. On April 20, 1836, Santa Anna made camp on a grassy field near the confluence of the San Jacinto River and Buffalo Bayou. Water and Texians hemmed in the Mexican army, so that night General Houston went to bed with orders not to be disturbed. The next morning he held a war council, after which he ordered a bridge over the San Jacinto destroyed, “for it cut off all means of escape for either army.” In short the coming battle would spell “victory or death.”

At 3:30 that afternoon, during the traditional Mexican siesta, Houston mounted his horse and led his Texians into a battle that lasted only 18 minutes. Santa Anna’s troops had been quite literally caught napping, but despite Houston’s protests, the Texians indulged their bloodlust. With cries such as “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” they slaughtered Santa Anna’s troops, some of whom pleaded, “Me no Alamo.” By day’s end more than 600 Mexicans lay dead, hundreds more were wounded and several hundred were captives. The Texians had 30 casualties, nine dead.

Houston himself had been severely wounded when a musket ball smacked into his right leg above the ankle, shattering bone and filling his boot with blood. Yet he stayed in the saddle until his horse—one of two shot from beneath him—collapsed, and his men guided the general off the battlefield.

An American patrol had unwittingly captured Santa Anna, who had shucked his general’s uniform to don a common soldier’s clothing as a disguise. The ploy didn’t work. As the patrol rode back to camp with the “bedraggled little figure,” Mexican soldiers saluted him with cries of, “El Presidente!” Realizing the game was up, Santa Anna asked to be conducted to General Houston.

The Texians wanted the dictator executed, but Houston knew better. “Texas, to be respected, must be polite,” he reportedly said. “Santa Anna living can be of incalculable benefit to Texas; Santa Anna dead would just be another dead Mexican.” Despite the pain from his grievous wound he personally negotiated terms with the self-styled “Napoléon of the West.” Texas had won its independence with the April 21, 1836, victory. Sam Houston had won even greater fame, earning the nickname “Old Sam Jacinto.”

Elected president of the Republic of Texas in a landslide later that year, Houston would remain a public figure for the rest of his life: president of Texas again (1841–44), a leader in the move to add Texas to the Union in 1845, U.S. senator (1846–59) and governor (1859–61). By the time he reached the Governor’s Mansion, however, the secessionist movement had reached a war-eager pitch, and Houston—ever the Jacksonian Democrat and fervent Unionist—was soon to fall from hailed hero to despised villain. On March 16, 1861, when Texas officials gathered to swear individual oaths of allegiance to the Confederacy, Houston remained in the Capitol basement doing what he loved to do—whittle.

Texas kicked him out of office but could not shut him up. For the rest of his life Houston spoke against secession, warned what war would reap—even when Sam Jr. joined the Confederate army. “Once I dreamed of an empire for a united people,” he said in an 1863 speech in the bustling Texas railroad town named for him. “The dream is over.”

In 1839 Houston had met Margaret Lea on a trip to Mobile, Alabama. They married the following year, and she had the strength to temper most of Houston’s demons. By 1851 he had even stopped drinking. Even on his deathbed, when doctors suggested a sip of brandy, he adamantly refused.

Having sold their home in Huntsville in 1858, the Houstons returned there in 1862, renting the Steamboat House. An Austin College professor had designed and built the house in 1858, flanking its front porch with twin turrets that resemble the stacks of a steamboat. Tradition holds it was a wedding present for the professor’s son. “The wife refused to live there,” says Michael C. Sproat, curator of collections at Huntsville’s Sam Houston Memorial Museum, where the house now stands. “But Sam Houston liked it.”

It was there Houston, in the loving company of Margaret and their children, died. And it was there Margaret slipped off the ring Houston had worn most of his adult life. That night she wrote in the family Bible:

Died on the 26th of July 1863, Genl Sam Houston, the beloved and affectionate Husband and father, the devoted patriot, the fearless soldier—the meek and lowly Christian.

It was a fitting epitaph, but the ring she showed her sons and daughters defined Sam Houston even better. Inscribed inside the gold band was a single word: Honor.

Special contributor Johnny D. Boggs has won Spur and Wrangler Awards for his fiction and is preparing a novel about Sam Houston’s last years. Also see Sam Houston, by James L. Haley; The Raven, by Marquis James, and Seat of Empire: The Embattled Birth of Austin, Texas, by Jeffrey Stuart Kerr

Originally published in the April 2015 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.