Some called them the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers, though they included a contingent from Logan County, Kentucky, and members from other states. Some called them “Crockett’s band,” though William Harrison, not Col. David Crockett, was their captain.

One, James M. Rose, was the nephew of fourth U.S. President James Madison, while another, Richard Stockton, boasted a signer of the Declaration of Independence in his family line. The families of Dr. John Purdy Reynolds of Pennsylvania and Micajah Autry of Tennessee erected grave markers in their respective hometowns, though the “graves” contained no remains, as Mexican troops had burned the bodies of all the Texian defenders, save one, after taking the Alamo.

As the Alamo siege ended on March 6, 1836, none of the Tennessee volunteers had been in Texas more than three months. Though Eastern newspapers published fragmentary casualty lists that included all their names, a fictional publication attributed to their most celebrated member, David Crockett, ultimately eclipsed their memory.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

CAPITALIZING ON EXPLOITS

With the late summer 1836 release of Col. Crockett’s “Exploits and Adventures” in Texas the frontiersman’s Philadelphia publishIng house, Carey & Hart, sought to capitalize on his unexpected demise in far-off San Antonio, Texas. While Crockett’s 1834 autobiography, “A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett,” had sold very well, a second work attributed to him, An Account of Col. Crockett’s “Tour to the North and Down East” (1835), had fared not nearly as well, many copies remaining unsold.

Publishing house partners Edward L. Carey and Abraham Hart aimed at recouping their losses by turning out a third book ostensibly “written by himself.” They engaged a writer named Richard Penn Smith, who cobbled together several 1835 letters by the late Tennessee congressman, observations from Mary Austin Holley’s Texas travel memoir and tidbits from other Texas narratives with purely invented passages, including excerpts from a bogus “journal” Crockett supposedly kept up to the day before Mexican troops stormed the Alamo walls.

In place of the real men who had sided with Crockett at the Alamo, “Exploits and Adventures” had the colonel traveling with four companions: Ned, a young bee hunter (a character borrowed from James Fenimore Cooper’s “Leatherstocking Tale The Prairie,” an 1827 novel also published by Edward Carey); Thimblerig, a low gambler from Natchez who plied the shell game; an Indian hunter; and an aging pirate.

Publishers have since reprinted “Exploits and Adventures” in conjunction with the legitimate narrative, thus spin-off accounts of Crockett’s final exploits have often inserted this picaresque quartet in place of the 16 men who actually accompanied him.This is unfortunate, as it diminishes the real men of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers and obscures the motives behind those who launched the Texas Revolution.

FADING INTO HISTORY

The Tennessee Mounted Volunteers fared no better in memory as years rolled by. Edwin Justus Mayer’s 1941 play Sunrise in My Pocket adopted Richard Penn Smith’s cast of characters, as did many other adult and juvenile Crockett biographies to follow.

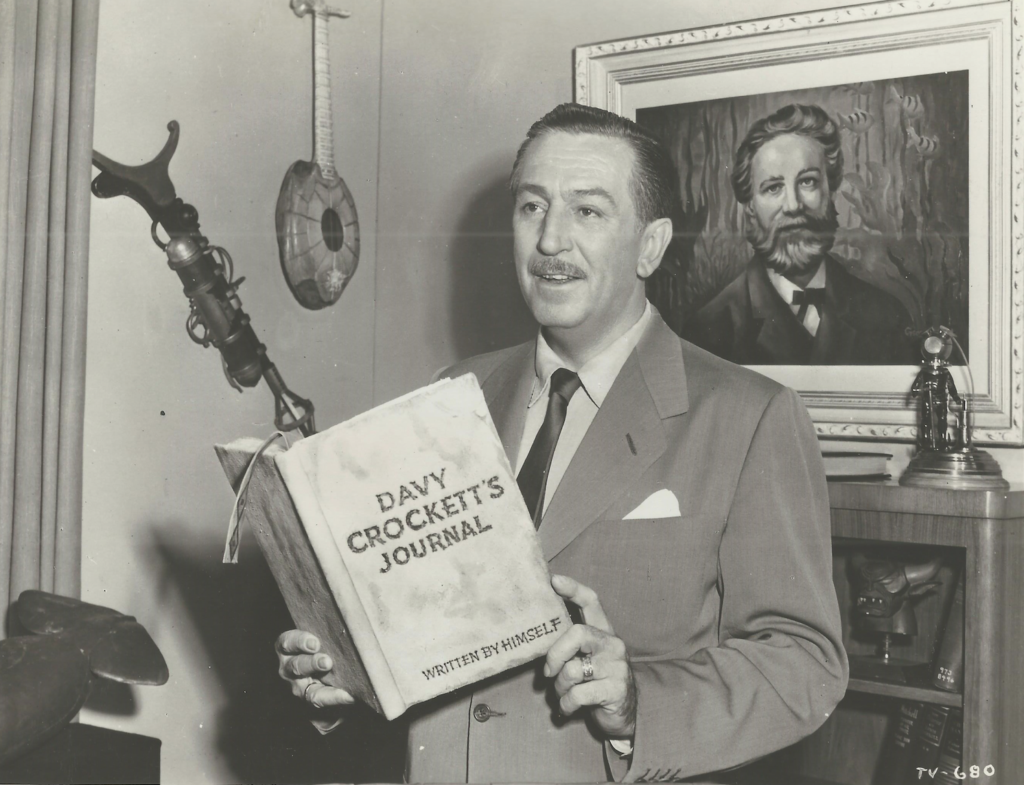

Walt Disney’s televised serial “Davy Crockett” (1954–55), which reintroduced the “King of the Wild Frontier” to 20th-century children and adults, retained two of the “Exploits” characters —Thimblerig the gambler (played by Hans Conried), and the Indian (Nick Cravat), whom the Disney screenwriters named Busted Luck. In John Wayne’s 1960 epic The Alamo Crockett’s companions become a band of boozing, brawling backwoodsmen —played by such veteran character actors as Chill Wills, Denver Pyle and Chuck Roberson—all of whom had followed “the colonel” for years through various frontier scrapes.

In the 2004 Alamo film, starring Billy Bob Thornton as Crockett, the colonel’s fellow Tennesseans are largely anonymous, the exception being Micajah Autry (Kevin Page), who seems to function as Crockett’s manager or press agent; “He prefers David,” Autry primly rebukes an Alamo defender who addresses Crockett as “Davy.”

THE REAL MEN AT THE ALAMO

David Crockett was a celebrity when he went to the Alamo, and he has emerged as the biggest hero among the heroic defenders who died there. But the men who came there to fight alongside him should not be forgotten. From Texas land claims, letters and family recollections, it is possible to recover some sense of the real Tennessee Mounted Volunteers.

On Dec. 7, 1835, Micajah Autry wrote wife Martha in Jackson, Tenn., to say he had reached Memphis and was commencing the long journey to Texas. “I have taken my passage on the steamboat Pacific,” he wrote, “and shall leave in an hour or two.”

Others aboard Pacific, Micajah told Martha, were also “bound for Texas.” One, he noted, believed “the fighting will be over before we get there and speaks cheeringly of the prospects.” Autry himself remained upbeat. “I feel more energy than I ever did in anything I have undertaken,” he wrote. “I am determined to provide for you a home or perish.”

A practicing attorney and War of 1812 veteran of a North Carolina regiment, Autry, 42, was older than many starting for Texas. The sometime painter, poet, teacher and failed merchant was looking for a new home for Martha and their two small children after serious business reverses. He picked the rebellious Mexican province of Texas, which since 1821 had seen an influx of Anglo settlers at the invitation of the Mexican government, but which a few months before had risen in revolt against that government and its army under dictatorial General Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Kentucky lawyer Daniel William Cloud, making a meandering journey through Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas and Louisiana, explained the Texian conflict in a December 26 letter to his brother: “Our Brethren of Texas were invited by the Mexican Government, while Republican in its form, to come and settle; they did so; they have endured all the privations and suffering incident to the settlement of a frontier country.…Now the Mexicans with unblushing effrontery call on them to submit to a Monarchical, Tyrannical Central despotism,” enforced by Santa Anna. “Every true hearted son of Ky. feels an instinctive horror, followed by a firm and steady glow of virtuous indignation.”

Arriving at the old French settlement of Natchitoches, La., Cloud traveled with another “son of Kentucky,” fellow lawyer Peter James Bailey III. Better educated than Cloud, who had followed the conventional practice of reading law with a senior Kentucky practitioner, Bailey had actually studied jurisprudence at Transylvania University in Lexington, graduating in 1834, the year before his arrival at the jumping-off point for Texas.

Autry’s steamboat had made Natchitoches about 10 days before Cloud and Bailey hit town. “The war is still going on favorably to the Texans,” Micajah reassured Martha. “It is thought that Santa Anna will make a descent with his whole forces in the spring, but there will be soldiers enough of the real grit in Texas by that time.”

OFF HUNTING BUFFALO

Meanwhile, David Crockett was out hunting buffalo on the Texas plains. He had come by a different route than Autry, Cloud and Bailey, traveling through Arkansas and then overland across the Red River into Texas. Embittered over his unsuccessful bid for re-election as he left Tennessee that November, Congressman Crockett told Memphis constituents that since they had preferred Adam Huntsman over him as their representative, “You may all go to hell, and I will go to Texas.” He had vowed to “explore the Texes [sic]” before returning to the States. Years later Crockett’s youngest child, Matilda, recalled the family had not known “he intended going into the [Texas] army.” Others, however, had presumed he would join the fight and were surprised when he seemed to disappear.

Eastern traveler Edward Warren wrote from Washington-on-the-Brazos, Texas, on Jan. 1, 1836: “You may have heard that David Crockett set out for this country with a company of men to join the army. He has forgotten or waved [sic] his original intention & stopped some 80 to 100 miles to the north of this place to hunt Buffalo for the winter.” Crockett had lamented in his “Narrative” that buffalo had been hunted out of his native Tennessee, so the bear hunter had clearly jumped at the opportunity to pursue new game.

But a week after Warren voiced his disapproval of Crockett’s decision, Davy did surface in a round of speeches and parties between San Augustine and Nacogdoches, Texas, in “excellent health…and high spirits,” he wrote daughter Margaret and her husband back in Tennessee. “As to what I have seen of Texas, it is the garden spot of the world.…There is a world of country to settle…[with] every appearance of good health and game plenty.”

He was back on task as he rode to Nacogdoches. “[I] have enrolled my name as a volunteer for six months,” he continued, “and will set out for the Rio Grande in a few days with the volunteers from the United States.…I had rather be in my present situation than to be elected to a seat in Congress for life.” Judge John Forbes, who had administered the oath of allegiance to Crockett, used the standard form oath that required the volunteer to pledge to support the Texian provisional government “or any future government of Texas.”

Leading the Texians at the Alamo were Lt. Col. William B. Travis. (Texas State Library.)

Crockett, wary of executive power after years of fighting President Andrew Jackson, insisted the oath be revised to pledge only to support “any future republican government.” Forbes, later reporting he had sworn in Autry, “the Celebrated David Crockett” and other volunteers, suggested this new contingent might fall in line to support the general council versus the governor. Though Crockett expressed interest in future political involvement in Texas, for the moment he was most interested in reaching San Antonio de Béxar.

In early 1835, with the provisional governor and council at odds and issuing contradictory orders, and General Sam Houston still lacking an army, the nascent revolution seemed in free fall. But volunteers kept arriving. Walking overland from Louisiana for lack of a mount, Micajah Autry had joined the army: “I have become one of the most thoroughgoing men you ever heard of,” he wrote Martha from Nacogdoches on January 13. “I go the whole Hog in the cause of Texas.” He again sought to reassure his wife: “Be of good cheer, Martha, I will provide you a sweet home.” A postscript brought news of another’s arrival: “Colonel Crockett has just joined our company.”

The “company” assembling at Nacogdoches by then included Daniel Cloud and friend Peter Bailey, and Pennsylvania physician Dr. John Purdy Reynolds and friend William McDowell. Among the older volunteers, at age 41, McDowell had moved from Mifflin County, Pa., to a new settlement named Mifflin in Tennessee; but as writer Michael Lind notes in his 1995 book “The Alamo: An Epic,” “There would be no Mifflin, Texas.”

Another Tennessee transplant, Ohio-born William B. Harrison, had been sworn in as captain of the band, soon dubbed the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers. North Carolina physician Dr. John Thomson had joined the group, as had 18-year-old Virginian Richard L. Stockton.

Stockton claimed kinship with Richard Stockton of New Jersey, a signer of the Declaration of Independence who had been captured by the British and had suffered horribly before being paroled. The men saw themselves as following in the footsteps of their Revolutionary War forebears. “Inheriting the old Saxon spirit of 1640 [and] 1776 in America,” Cloud had written a friend in Kentucky, “the inhabitants of Texas throw off the chains of Santa Anna.”

By then Crockett may already have left Nacogdoches at the head of a smaller “spy” or scout company; at least one volunteer, 18-year-old Kentuckian B.A.M. Thomas, is known to have accompanied him. In leisurely fashion the little group made its way to San Antonio de Béxar, scouting possible homesteads along the route.

They clearly expected the future government of Texas to establish a generous land distribution system much more attractive to struggling settlers than the public lands system they had left behind in the States. “I shall be entitled to 640 acres of land for my services in the army,” Micajah Autry had written Martha, “and 4,444 acres upon condition of settling my family here.” Crockett—who had battled on the House floor to permit his “squatter” constituents to keep their patches of Tennessee farmland—exalted in a new country where “it is not required here to pay down for your League of land,” which he correctly defined as 4,428 acres. “They may make the money to pay for it on the land.” Cloud thought the same. “[Texas] is immense in extent and fertile in its soil,” he wrote, “and will amply repay all our toil.”

The path of the little company is traceable through vouchers signed by Crockett and others for food and lodging en route. “This is to testify,” reads one example, “that we on behalf of a squad of volunteers traveling to St. Antonio, being out of provisions, called upon John Y. Criswell, who fed us in his own house with his own provisions for the night & next mornings breakfast, eight of us 2 meals @ 25 cts. Say five dollars, for which the government will no doubt remunerate him, we being authorized to draw on said gov. for provision.” The voucher, dated February 11, was signed by M. Autry and D.W. Cloud.

MEANWHILE IN SAN ANTONIO

In San Antonio the small body of Texians led jointly by Lt. Col. William B. Travis and Colonel James Bowie had forted up in an old Spanish mission known as the Alamo, across the river from town. General Sam Houston had ordered Bowie to destroy the fortifications in town, but he was equivocal about whether also to blow up the Alamo, advising provisional Governor Henry Smith, “If you think well of it, I will.” Around the same time Smith had ordered Travis to lead a small group of Texian reinforcements to San Antonio. Bowie and Travis both concluded the Alamo should be held.

The Tennessee Mounted Volunteers had arrived in early February. In town Crockett ran into old friend James M. Rose. An Ohio-born nephew of President James Madison, Rose had moved with his family from Virginia to Tennessee following the death of his mother, the president’s sister. His brothers later remembered Rose as “a man of sanguine temperament about thirty years of age, about 5 ft. 7 or 8 inches high, of fair complexion, disposed to freckle, but rendered sallow by continued attacks of chill & fever before he went to Texas, was partially bald on the top of his head, hair sandy, eyes light blue or grey.…Was apt to stammer when at all confused.”

Susanna Dickinson, wife of Alamo artillery Captain Almeron Dickinson, recalled that Rose fell in with Crockett, the pair often taking meals at the Dickinson’s San Antonio home before the Mexican advance forced the Texians to the Alamo.

Col. Crockett declined a formal command, informing the troops he would serve as a “high private” to defend the “liberties of our common country,” though he had occupied that “common country” only a few weeks. Crockett asked Travis for an assignment, and the young commander requested that he and the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers defend a wooden palisade constructed between the Alamo chapel and south wall.

Susanna Dickinson later recalled that to amuse the troops, Crockett scratched away at an old fiddle while Scotsman John McGregor played the bagpipes. One wonders if Autry, an accomplished violinist, took a hand in providing music or simply looked on, wincing, as Crockett attempted a tune.

Santa Anna’s troops almost surprised the Texian garrison on February 22 as the rebels celebrated George Washington’s birthday with a fandango in San Antonio, but rain-swollen rivers delayed their advance. The next afternoon, as the Texians took refuge in the old mission, the siege commenced. The kin and friends of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers received no more letters. On March 6 the besieging army stormed the Alamo walls in darkness and overwhelmed the garrison. Mexican soldiers gathered the bodies of all the defenders, except Gregorio Esparza (whose brother was among Santa Anna’s officers), stacked them atop scrap wood and burned them.

Given the communications of the day, news of the Alamo’s fall was slow in reaching the States. Micajah Autry’s family, recalled daughter Mary, got the “awful news…one lovely April morning.” The families of several of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers, including that of David Crockett, received the land their men had earned from the new Republic of Texas, once Houston had defeated Santa Anna at San Jacinto that April 21. “If we succeed,” Daniel Cloud had written, “the Country is ours.…If we fail, death in the cause of liberty and humanity is not cause for shuddering.”WW

TENNESSEE MOUNTED VOLUNTEERS ROSTER

Sources vary as to the identities of all members of the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers who followed Davy Crockett to San Antonio and the Alamo. This roster follows the list compiled by Alamo experts Phil Rosenthal and Bill Groneman for their 1985 book Roll Call at the Alamo.

Rosenthal and Groneman consulted muster lists of the chaotically organized Texas Army, as well as the 1931 dissertation by Texas historian Amelia Williams, “A Critical Study of the Siege of the Alamo and the Personnel of its Defenders,” subsequently reprinted in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly and in book form as The Alamo Defenders (2010).

Williams added a few names not accepted by Groneman and Rosenthal, including William H. Smith and John Harris. In alphabetical order, with approximate age at the time of the siege, birth state and, if different, the state each left to defend the Alamo, here are the Tennessee Mounted Volunteers:

1. Micajah Autry, 42, North Carolina; to Texas from Tennessee

2. Peter James Bailey III, 24, Kentucky

3. Joseph Bayliss, 28, Tennessee

4. Robert Campbell, 26, Tennessee

5. Daniel William Cloud, 24, Kentucky

6. David Crockett, 49, Tennessee

7. William Fauntleroy (also spelled Fontleroy or Furtleroy), 22, Kentucky

8. William B. Harrison (Captain), 25, Ohio; to Texas from Tennessee

9. William Irvine Lewis, 30, Virginia; to Texas from Pennsylvania

10. William McDowell, 41, Pennsylvania; to Texas from Tennessee

11. Dr. John Purdy Reynolds, 30, Pennsylvania; to Texas from Tennessee

12. James M. Rose, 31, Virginia; to Texas from Arkansas

13. Richard L. Stockton, 18, Virginia

14. B.A.M. Thomas, 18, Kentucky

15. Dr. John W. Thomson, 29, North Carolina

16. Joseph G. Washington, 28, Kentucky

Suggested for further reading: “A Narrative of the Life of David Crockett,” Written by Himself and David Crockett: “Hero of the Common Man,” by William Groneman.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.