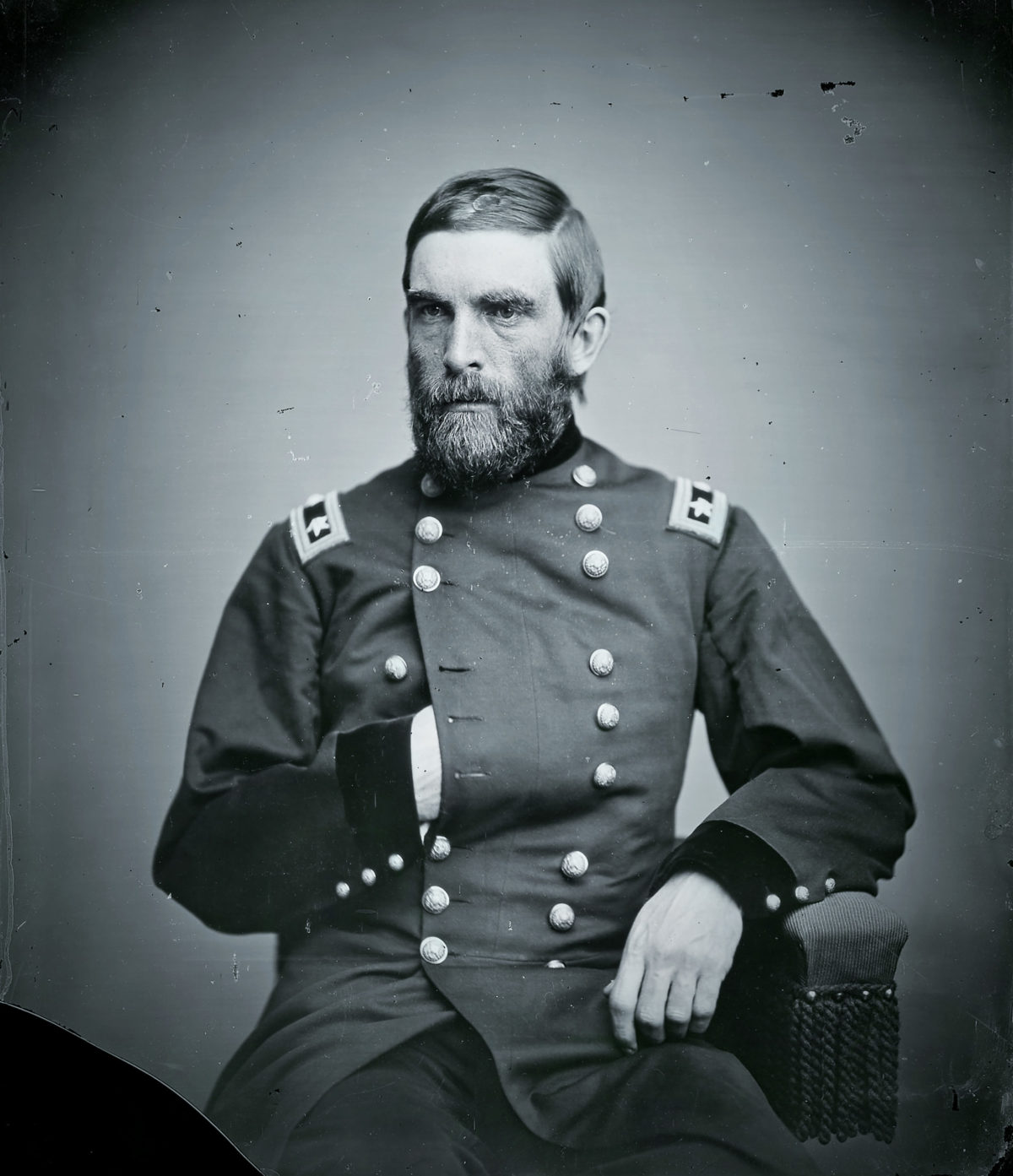

In describing Union Maj. Gen. Grenville Mellen Dodge to Ulysses S. Grant, his commander and friend, William Sherman usually kept it simple. “Dodge is a brick,” he once wrote Grant—perhaps the perfect compliment for a luminary who never quite made it into the Civil War Pantheon and continues to escape notice even today. Although Dodge fought in only two major battles—Pea Ridge in 1862 and Atlanta in 1864—his contributions to ultimate Union victory should not be underestimated. In Grant’s opinion, Dodge was both the best railroad-builder and best railroad-destroyer the war would see in either Army. He was, however, remarkable in many other ways.

Slight of built, weighing only 130 pounds, Dodge surely didn’t look like a brick. What did single him out was his incredible optimism, his indomitable will, and his love of action. A Massachusetts native and 1851 graduate of Vermont’s Norwich University—with a degree in civil engineering—he eventually relocated to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where he had an opportune meeting with Abraham Lincoln while Lincoln was stumping for the Republican Party’s 1860 presidential nomination. He shared Lincoln’s vision for a transcontinental railroad and would use his influence at the 1860 Republican Convention to win Iowa for Lincoln.

After Fort Sumter in April 1861, Dodge dissolved his business interests and, at Governor Samuel J. Kirkwood’s behest, traveled to Washington, D.C., to obtain arms for Iowa volunteer regiments. There, he was offered colonelcy of the 4th Iowa Infantry. “I go into this war on principle, [which] pecuniarily will ruin me,” Dodge wrote his mother. “I put my trust in God; if I come out safe, I hope no one will have cause to regret my course.”

Recommended for you

As senior officer at Fort Wyman in Rolla, Mo., Dodge was known to drill his men relentlessly, even before they had their weapons, uniforms, or equipment. While in Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont’s Western Department, Dodge created what he later called his “secret service.” Frustrated his cavalry often embarked on fruitless scouting excursions in response to enemy sightings, Dodge learned that the men in one independent Missouri cavalry unit were locals and were willing, if paid, to serve as his scouts in the region. It was a welcome proposal, and Dodge worked with his provost marshal to use funds that were collected through fines and related methods to support the spies’ endeavors. “I followed it throughout my service,” Dodge later wrote, “and found it of great benefit.”

On a visit to St. Louis in October 1861, Dodge began personally outfitting the 4th Iowa. According to one soldier’s letter to the Council Bluffs newspaper: “Through [his] exertions…the 4th has been provided with a full outfit, from head to foot of winter clothing, of excellent material, well-made up. Also, extra heavy overcoats for wintry days…new equipment of arms, knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc.”

The overcoats were black, which would be of particular note during the March 1862 fighting at Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern) in Arkansas.

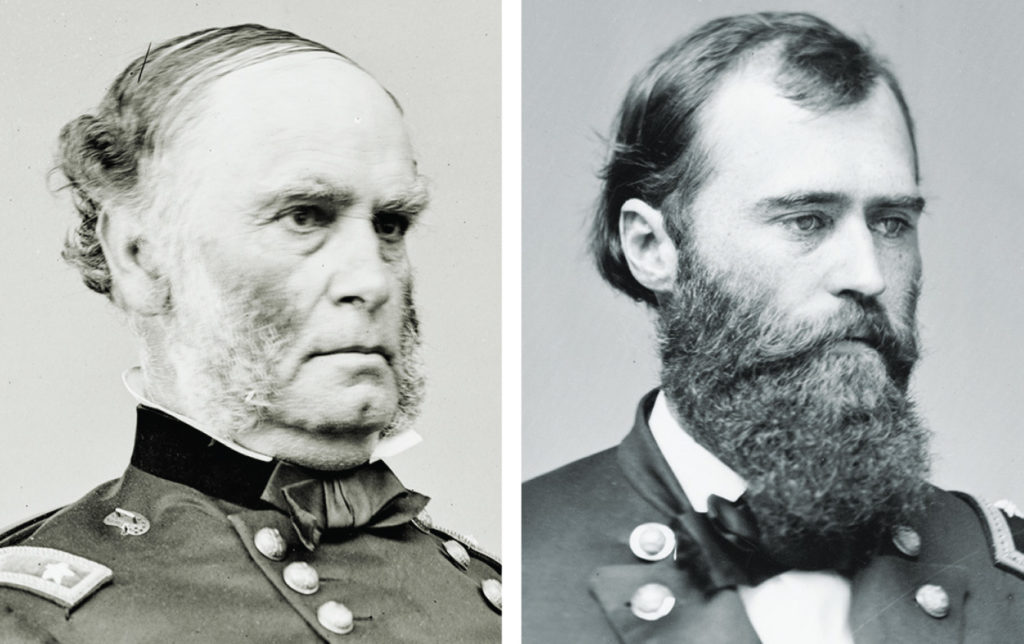

Dodge was with Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis’ Army of the Southwest in December 1861 when he met another budding young luminary, Phil Sheridan. A captain at the time, Sheridan was the army’s quartermaster; Dodge commanded the 4th Division’s 1st Brigade. The two shared a tent, and Dodge listened intently as “Little Phil” complained about untrained officers who refused to limit the size of their wagon trains or to help forage for supplies. Dodge decided to follow Sheridan’s example with his own men.

Never a fan of Sheridan, Curtis would eventually relieve Little Phil from his army—the exact reason why has never been fully substantiated. Sheridan praised Dodge in his memoirs: “Several times I was on the verge of personal conflict with regimental commanders, but Colonel Dodge so sustained me before General Curtis and supported me by such efficient details from his regiment—the 4th Iowa—that I shall hold him and it in great affection and lasting gratitude.”

Earlier in the war, the principal Federal force in the region was known as the Army of the West. It was tasked with driving the Confederates out of Missouri, but the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in August 1861 had been a resounding defeat and had cost then-commander Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon his life. The Rebel force at Wilson’s Creek was composed of Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCulloch’s Western Army and the Missouri State Guard under Maj. Gen. Sterling Price, still not a formal Confederate force, as hotly contested Missouri had yet to secede (and never did).

The disputatious Price quarreled with McCulloch, however, compelling the famed former Texas Ranger to return to Texas in outrage. That caught President Jefferson Davis’ attention. He assigned Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn command of what was to be called the Trans-Mississippi District of Department No. 2 and instructed McCulloch to return with his force to Missouri. In addition to Price’s and McCulloch’s commands, Van Dorn had the services of Brig. Gen. Albert Pike and about 1,000 Cherokee and Creek warriors—a combined force of roughly 16,500 men.

By the end of the year, with the Confederates now camped in northern Arkansas, Davis directed Van Dorn to move back into Missouri, defeat Curtis, and then head to St. Louis—an important Mississippi River base for contesting Ulysses S. Grant’s forces in the Western Theater. Van Dorn had assumed command knowing little about the region’s terrain or the officers now under his command. He was reassured, however, by the fact his troops outnumbered Curtis’ Federals.

In late February, Van Dorn began moving toward Curtis’ army straddling the Missouri–Arkansas border. Knee-deep snow greatly hindered the Confederate advance, but Van Dorn’s decision to leave his supply wagons behind for speed would be a regrettable mistake.

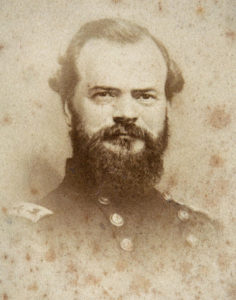

Dodge’s spies proved instrumental in the buildup to the fighting at Pea Ridge when they uncovered Van Dorn’s decision to split his army in order to attack Curtis’ rear. In command of five companies of the 4th Iowa and two companies of the 3rd Missouri Cavalry, Dodge “felled all the timber I could” across a key thoroughfare known as the Bentonville Detour to block the advance of Van Dorn’s and Price’s separated troops for several hours.

The delay factored significantly in the Federals’ Pea Ridge victory on March 8. Had the Southern troops succeeded in flanking Curtis’ army as Van Dorn intended, the battle’s outcome may well have gone the other way.

Early on March 7, Dodge met with Curtis and fellow officers to deliberate plans for the coming battle. Dodge was “confident of [an] attack on our rear and right” and had his men break camp and follow him to the command council. Curtis soon learned that the pickets in Colonel Sempronious H. Boyd’s 24th Missouri Infantry were being driven in and ordered his army to completely reverse its position—putting Dodge now on the army’s right flank. Curtis then ordered Dodge to march up the Telegraph Road toward Elkhorn Tavern.

Although Dodge had only 1,260 men (950 infantry, 310 cavalry) against Price’s three divisions, he held fast with the adroit use of his artillery, positioned behind a rail fence.

At one point, Van Dorn rushed forward several batteries and went into action against Federals positioned in a hollow just off the Telegraph Road. To counter the Confederate build-up on his right, Dodge realigned his front. He ordered two guns placed on the Huntsville Road by Lieutenant Virgil A. David to open fire, and requested help from 1st Division commander Eugene A. Carr, who lent him his only reserve force—Colonel David Shunk’s 8th Indiana Infantry. The collapse of Colonel William Vandever’s 2nd Brigade on the other side of Telegraph Road put Dodge in danger of envelopment on the right, but he turned Price back by rushing in Shunk’s reserves.

Despite having three horses shot out from beneath him and suffering wounds to his side and hand, Dodge remained in the fray. But when the Confederates surged forward again at about 5 p.m., and with his men running out of ammunition, Dodge finally fell back about a half-mile to re-form his troops. While retiring, his men halted long enough to unleash a series of well-aimed volleys at the pursuing Rebels.

Left behind in a house filled with Union wounded was Charles A. Baker, a hospital nurse. Price asked Baker for the identity of the man in the black coat who commanded the Federals. Informed it was Colonel Dodge of the 4th Iowa, Price replied, “Give my compliments to him and say to him that he has given me the best fight I ever witnessed.”

Newspaper coverage of the victory quickly made Dodge a national hero. As T.J. McKenny, Curtis’ acting adjutant major, noted: “Col. Dodge of the 4th is a lion. The 4th and the 9th [Iowa] fought like tigers. One third fell in battle[,] no prisoners taken.”

Defending the Rails

As he recovered from his wound, Dodge was promoted to brigadier general, and in June was assigned to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck’s Department of the Missouri in Corinth, Miss. At Halleck’s headquarters, Dodge came upon an old acquaintance, Sheridan, about to be appointed colonel of the 3rd Michigan Cavalry.

Assigned an 8,000-man division, Dodge was dispatched to repair of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad between Corinth and the Ohio capital, Columbus. In this role, Dodge created a “Pioneer Corps,” a unit made up primarily of contrabands and used for “repair or construction work needed during the War.” Dodge was an able antagonist to Confederate Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who was conducting raids between the Tennessee towns of Grand Junction and Jackson. Destruction of railroad bridges in his path was one of Forrest’s specialties, but he often found himself checked along Dodge’s Mobile & Ohio lines.

A factor for that was Dodge’s decision to have two-story blockhouses and stockades built along the line’s bridges and stations. Each would be assigned at least a single company, usually a force strong enough to hold off enemy threats (such as Forrest’s cavalry) long enough for reinforcements to arrive. Grant was so impressed by Dodge’s novel approach that upon becoming commander of West Tennessee he ordered all bridges and stations along the region’s railroads fortified in this manner.

When Colonel John Rawlins, Grant’s chief of staff, recommended that Grant and Dodge meet so his commander would have an opportunity to test the Iowan’s mettle, Grant agreed. Dodge showed up for that meeting in Jackson, Tenn., still dressed in old trousers stuffed inside muddy boots, wearing a simple soldier’s blouse and a sagging hat. Worried about his appearance, Dodge would be reassured by Rawlins: “Never mind about the clothes. We know all about you.” Dodge later admitted he felt better once he saw Grant’s own uniform.

Grant gave Dodge command of the Army of the Tennessee’s 2nd Division and instructed him to ramp up his secret service system in order to determine the enemy’s overall strength.

Some of Dodge’s spies were illiterate, and Dodge was known to take various approaches in training them. He had his agents memorize key information and made sure they could provide accurate troop counts of those traveling either on foot or by train. Knowing that an apprehended spy faced likely death, Dodge advised them to be as forthright as possible if captured. They were not to obfuscate the truth about Union forces, in order to give the impression they were regular civilians.

For Dodge, report accuracy was a must. He would interview refugees and contrabands, read Southern newspapers, and have captured Rebels interrogated—and he would train his men in what he felt was the best manner to cross-examine prisoners. When satisfied that the intelligence was correct, Dodge then forwarded it to Grant and other officers. He kept the list of his agents to himself; only his adjutants general and provost marshals knew of his intelligence operations.

Agents were to communicate with Dodge only indirectly. They were to carry Confederate money, gold, and goods to help bribe and barter behind the lines. At times, some even joined the Confederate army or pretended to be Confederate spies. Female spies were particularly valuable assets in towns where Confederates were known to be posted.

Concerned about the money he was spending, Dodge queried Grant: “I respectfully request instruction to me in relation to the secret service fund….The question is how much discretion I have in this matter and how can I account for this money.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Dodge realized he could secure funds for his agents by selling cotton, and in January 1863 asked, and received, permission from Grant to retain all proceeds from the sale of contraband cotton to finance his intelligence operations. Long after the war, however, the Treasury Department wrote to Dodge—then president of the Union Pacific Railroad—seeking $17,099.95 “standing against you on the books of this office of secret service funds placed in your hands during the late war.” Dodge simply forwarded the demand to the War Department.

With rumors circling that Dodge was enriching himself by speculating in cotton, Grant told him simply to “grin and bear it.”

Dodge spent 1862-63 defending Grant’s flank, chasing Forrest, repairing railroad lines, and destroying one of the breadbaskets that helped feed the Confederate army. At one point, he recalled, a two-mile line of contrabands from the “broad and fertile Tennessee Valley followed us. They came with their families loaded in all kinds of vehicles…they were the most motley and picturesque crowd that I ever saw.”

Giving them a home at a deserted plantation and placing a 27th Ohio chaplain in charge, Dodge created what the famed Rev. John Eaton championed was one of the Union army’s most successful “Contraband Camps.”

‘Axes, picks, and spades’

Although he desired field action, Dodge knew Grant wanted him “in command of the District of Corinth; that it was a more important command than a division in the field as it held his flank. He…left me there because he knew I would stay, which was an indication to me that he expected me to stay no matter what force came against me.”

For Army of the Tennessee commander Sherman, Dodge’s health was a constant concern, as Dodge’s weight had dropped to about 125 pounds in the summer of 1863. When General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee pinned the Union army down in Chattanooga after the Battle of Chickamauga, Sherman ordered Dodge’s division up the Tennessee River Valley. It was Dodge’s assignment to repair and guard rail lines and roads between Nashville and Decatur, Ala.—needed by Grant to supply thousands of Federal troops. Dodge did not disappoint.

In his Personal Memoirs, Grant called Dodge a “most capable soldier” and applauded his ingenuity: “He had no tools to work with except those of the pioneers—axes, picks, and spades. With these he was able to intrench his men and protect them against surprise by small parties of the enemy.”

Without access to a dependable supply base, Dodge had his men forage for grain and cattle, and had millers and blacksmiths within his ranks use local mills and shops to grind flour and cornmeal and make tools for railroad- and bridge-building. Others cut timber for bridges, stacked cordwood, or built water tanks.

Marveled Grant: “The number of bridges to rebuild was 182, many of them over deep and wide chasms; the length of road repaired was 102 miles.”

Action in Atlanta

In March 1864, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general and made Union Army General-in-Chief. Sherman took control of the Military Division of the Mississippi, and Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson assumed command of the Army of the Tennessee. This also meant a return to the front for Dodge, whom Grant advised Sherman “is too valuable an officer to be anywhere except at the front and one you can rely upon in any and every emergency.” Sherman was content to keep Dodge with him, giving him command of the 16th Corps.

On July 10, 1864, Sherman asked Dodge to build a double-tracked trestle over the Chattahoochee River at Roswell, Ga. Three destroyed factories provided material for the bridge, although the owner of one of those factories, which flew a French flag, launched a protest to Dodge, who in turn telegraphed Sherman for advice on avoiding a potential international incident. “I know you have a big job but that is nothing new for you…,” was Sherman’s matter-of-fact response. “I know that the bridge at Roswell is important so that you may destroy all Georgia to make it good and strong.” The bridge would be finished by July 12.

It was ironic that Dodge had benefited the Union war cause thus far mostly by building and repairing railroads, but as the Atlanta Campaign progressed, he was directed by Sherman to destroy railroads feeding Georgia’s important commercial hub city—the Western & Atlantic in particular. Dodge’s men created what were famously known as “Sherman’s neckties.” They would remove rails; stack up the wooden ties beneath, set them on fire, and then heat the rails; and once the rails were heated twist them into all sorts of contortions, sometimes doing so around trees.

General Joe Johnston’s Confederates had bent but not yet broken in delaying Sherman’s advance on Atlanta that summer, but Davis clearly believed a more aggressive response was needed from his commander and, on July 17, finally replaced Johnston with General John Bell Hood. Dodge learned of the change on July 19 when one of his spies showed him an Atlanta newspaper. Dodge sought out and informed Sherman, who was conferring with Army of the Ohio commander Maj. Gen. John Schofield. Knowing Hood well from their West Point days together, Schofield predicted a Confederate attack within 24 hours.

He was correct. With Sherman’s army divided, Hood went after Maj. Gen. George Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland at Peachtree Creek on July 20. The Confederate attack, though, was delayed, and despite some initial success for Hood, the Federals prevailed. The loss cost the Confederates about 5,000 total casualties.

Meanwhile, the Army of the Ohio and Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee had moved to the east around Atlanta. On July 22, those forces clashed with Hood’s Confederates on the outskirts of the city in what would be known as the Battle of Atlanta. Hood ordered three divisions under Lt. Gen. William Hardee to attack the Union left, where McPherson had placed Dodge’s 16th Corps. Two attacks by Hardee were turned back.

Riding forward for a firsthand look, McPherson was exuberant at the 16th Corps’ determined stand and cried out “Hurrah for Dodge!” But as the popular Federal commander headed back he rode directly into a party of Confederates. Ordered to halt, he wheeled his mount to escape. Shots rang out, striking McPherson—killing him immediately.

With fewer than 5,000 men, the 16th Corps had faced at least three times their number. If he had retreated rather than stand and fight, Dodge later wrote, “What would have been the result? I say that in all my experience in life, until the two forces struck, and the Sixteenth Corps stood firm, I never passed more anxious moments.”

Major General Francis Blair, 17th Corps commander, concurred:

“I witnessed the first furious assault…and its prompt and gallant repulse. It was a fortunate circumstance for that whole army that the 16th Army Corps occupied the position I have attempted to describe, at the moment of the attack; and although it does not become me to comment upon the brave conduct of the officers and men of that Corps, still I cannot refrain from expressing my admiration for the manner in which [they] met and repulsed the repeated and persistent attacks of the enemy.”

Like Sherman, Dodge mourned McPherson’s loss. “[His] death was a loss to me personally,” he wrote. “Being an engineer himself he took interest in my railroad work during the campaign, and he also knew of General Grant’s friendship for me. In a kindly way giving me good advice.”

In meeting with Sherman to report on the battle, Dodge wrote “he seemed rather surprised to see me, but greeted me cordially, and spoke of the loss of McPherson. I stated to him my errand. He turned upon me and said, “Dodge, you whipped them today, didn’t you?” I said, “Yes, sir.” Then he said: “Can’t you do it again tomorrow?” and I said, “Yes, sir”; bade him good-night, and went back to my command, determined never to go upon another such errand.”

The Federal noose around Atlanta continued to tighten as July turned to August. On August 18, Sherman ordered Dodge to “feel the enemy’s front.” While in a trench manned by the 7th Iowa Infantry, Dodge was cautioned not to lift his head above the trench, instead shown an observation peephole they had made. But, as Dodge recalled, the moment he put his eye to the hole, “a rebel shot me in the head”. It was a significant wound, but fortunately not mortal. “Kittoe, Dodge isn’t going to die; he is coming to,” Sherman declared anxiously after asking his own medical director, Edward Kittoe, to examine the wounded warrior.

Left blind for several days, Dodge was sent north with other wounded soldiers in a freight car—lying in a hammock that apparently swayed with the rhythm of the train. At Marietta, Ga., a nurse who had joined his army in Corinth examined his wound and gave him some “delicacies,” being sure to share the rest of the food with the other wounded lying on the boxcar’s floor. A few of those soldiers recounted feeling lucky to have been in the same car as the general, knowing it meant they would likely get more attention and more to eat. “[A]ll the way they endeavored to help me,” lamented Dodge. “I was absolutely helpless.”

In October, Grant invited Dodge to his City Point, Va., headquarters and recommended he call on President Lincoln in Washington before returning home to Iowa. At their meeting, the president asked Dodge his opinion of Grant, receiving affirmation the general was confident Grant would defeat Robert E. Lee and end the war. Lincoln warmly clasped Dodge’s hands, saying, “You don’t know how glad I am to hear you say that.”

From the Union Army to the Union Pacific

The end of the war growing near, Dodge was given command of the Department of the Missouri, which had been combined with the Department of Kansas. Hostilities with American Indian tribes west of the Mississippi River remained an increasing threat for Dodge in his new command, particularly as it affected the region’s overland U.S. mail routes. He realized the November 1864 massacre of peaceful Southern Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians at Sand Creek by Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers had magnified the unrest, spurring united tribal attacks on civilians and U.S. authorities that impeded or outright halted settlers traveling west and gold shipments east.

In February 1865, Dodge sent word he was en route to Fort Kearny in the Nebraska Territory. When Grant reached out to Edward Creighton, creator of the historic Overland Telegraph company, to ask “Where is Dodge?” Creighton replied, “Nobody knows where he is, but everybody knows where he had been.” Long-delayed freighters, stagecoach lines, and wagon trains began rolling by April 1, and never stopped.

September 21, 1865, would be an especially memorable for Dodge when he and 12 cavalrymen came upon about 300 supposedly hostile warriors at Cheyenne Pass in present-day Wyoming. Watching the warriors disappear down a slope, Dodge ordered his men to follow and would discover a gradual, accessible descent to the plain below. By chance, he had found a long-sought pass for the pending Union Pacific railway.

Dodge left the Army in January 1866 and was offered the job of chief engineer of the Union Pacific. Assured he would have absolute control, he accepted and proved, as he had in uniform, to be a dynamic, hands-on leader. The Transcontinental Railroad was completed on May 10, 1869.

The friendships of Dodge, Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan welded by the war would last throughout their lifetimes. Notably, Dodge—whose health issues and wounds had once greatly alarmed Sherman—outlived the other three by at least 15 years. Dodge was 84 when he died on January 3, 1916.

The head of seven railroads and nine construction companies, and an adviser to various presidents, Dodge enjoyed fabulous wealth after the war. He was touched by scandal during Grant’s administration, as a friend of speculator Jay Gould, but he remained respected. He would lead fundraising efforts for memorials to Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan, as well as O.O. Howard, and after Grant died in July 1885 he led the seven-mile funeral procession for the former commander and president through New York City.

Dodge remained a friend to Grant’s widow, Julia, and children, and helped them financially—as he would for many widows and children of former generals, former spies, and 4th Iowa veterans who had fallen on hard times.

During a June 1902 event at West Point, Theodore Roosevelt gave Dodge an astonishing tribute: “I am going to say something to you that it will be hard for you to believe but it comes from my heart. I would rather have had your experience in the Civil War and have seen what you have seen and done than to be President of the United States.” No faint praise indeed.

Judith Wilmot writes from St. Augustine, Fla. She was the author of “Humanity Forbade Them to Starve” in the January 2021 issue of America’s Civil War.