The meeting between Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee in Wilmer McLean’s parlor at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, highlights the difficulty of pinning down historical details. One seemingly straightforward question about that famous moment illustrates the larger phenomenon. Was Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan in the room while Grant and Lee discussed surrender terms?

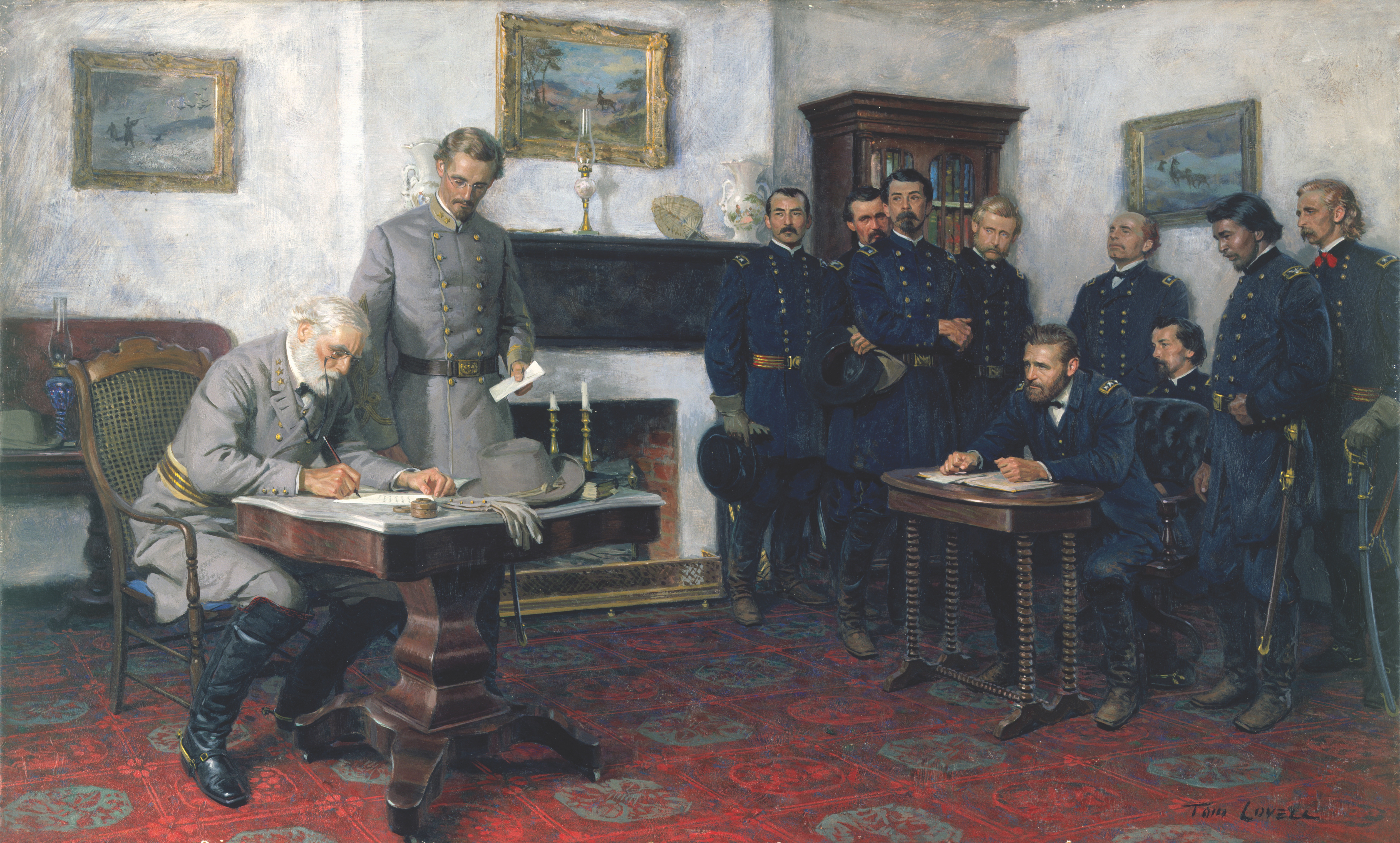

Artistic depictions seemingly provide the answer. An iconic image by Walter Taber, which appeared in Volume 4 of the Century Company’s immensely popular Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (1887-88), placed Sheridan on the far right, intently watching the seated Grant and Lee. Eighty years later, National Geographic Magazine commissioned Tom Lovell to paint the scene for the centennial of Appomattox. Lovell positioned Sheridan in the center of his composition, standing beside the parlor’s fireplace as Lee signed the surrender document. Lovell’s rendering earned many enthusiastic compliments as largely accurate (though it mistakenly portrayed George A. Custer as present). Innumerable other artworks also feature Sheridan in the room while Grant and Lee worked out details of the Confederate capitulation.

Members of Grant’s staff left several accounts. Colonel Horace Porter discussed the surrender in Battles and Leaders and also in Campaigning With Grant (1897). In both instances, Porter recalled Grant’s having Lt. Col. Orville E. Babcock summon Sheridan, Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord, and others into the parlor before the negotiations with Lee commenced. “We walked in softly and ranged ourselves quietly about the sides of the room,” Porter stated in Battles and Leaders: “Some found seats on the sofa and the few chairs that constituted the furniture, but most of the party stood.” In Campaigning With Grant, Porter located Colonel Charles Marshall of Lee’s staff “on the sofa beside Sheridan and [Brig. Gen. Rufus] Ingalls.”

Adam Badeau’s Military History of Ulysses S. Grant (1881) described “a naked little parlor” that the “generals entered, each at first accompanied only by a single aide-de-camp, but as many as twenty national officers shortly followed, among whom were Sheridan, Ord, and the members of Grant’s own staff.” The “various national officers,” Badeau added, were later “presented to Lee,” who bowed “to each, but offered none his hand.” Lieutenant Colonel Ely S. Parker, Grant’s military secretary, gave a postwar interview in which he identified staff members Porter, Badeau, Theodore S. Bowers, and Seth Williams, as well as “other officers” who either sat on the sofa or “stood in the doorways and hall.” Parker did not mention Sheridan.

Colonel Marshall featured Sheridan in his postwar narrative of the surrender. “I was sitting on the arm of the sofa…,” wrote Marshall, “and General Sheridan was on the sofa next to me. While Colonel Parker was copying the letter, General Sheridan said to me, ‘This is very pretty country.’ I said, ‘General, I haven’t seen it by daylight. All my observations have been made by night and I haven’t seen the country at all myself.’” Marshall also included Sheridan in a discussion about sending Union rations to Lee’s hungry soldiers. He quoted Grant instructing his lieutenant: “Order your commissary to send to the Confederate Commissary twenty-five thousand rations for our men and his men.”

Grant’s own memoirs allocated relatively little attention to what transpired in McLean’s parlor. “When I went into the house,” he noted, “I found General Lee. We greeted each other, and after shaking hands took our seats. I had my staff with me, a good portion of whom were in the room for the whole interview.” Later, while copies of the surrender documents were being prepared, “the Union generals present were severally presented to General Lee.” Grant did not name the generals, and his handling of the conversation with Lee regarding rations did not mention Sheridan. “I authorized him,” wrote Grant of Lee, “to send his own commissary and quartermaster to Appomattox Station, two or three miles away, where he could have, out of the [Confederate] trains we had stopped, all the provisions wanted.”

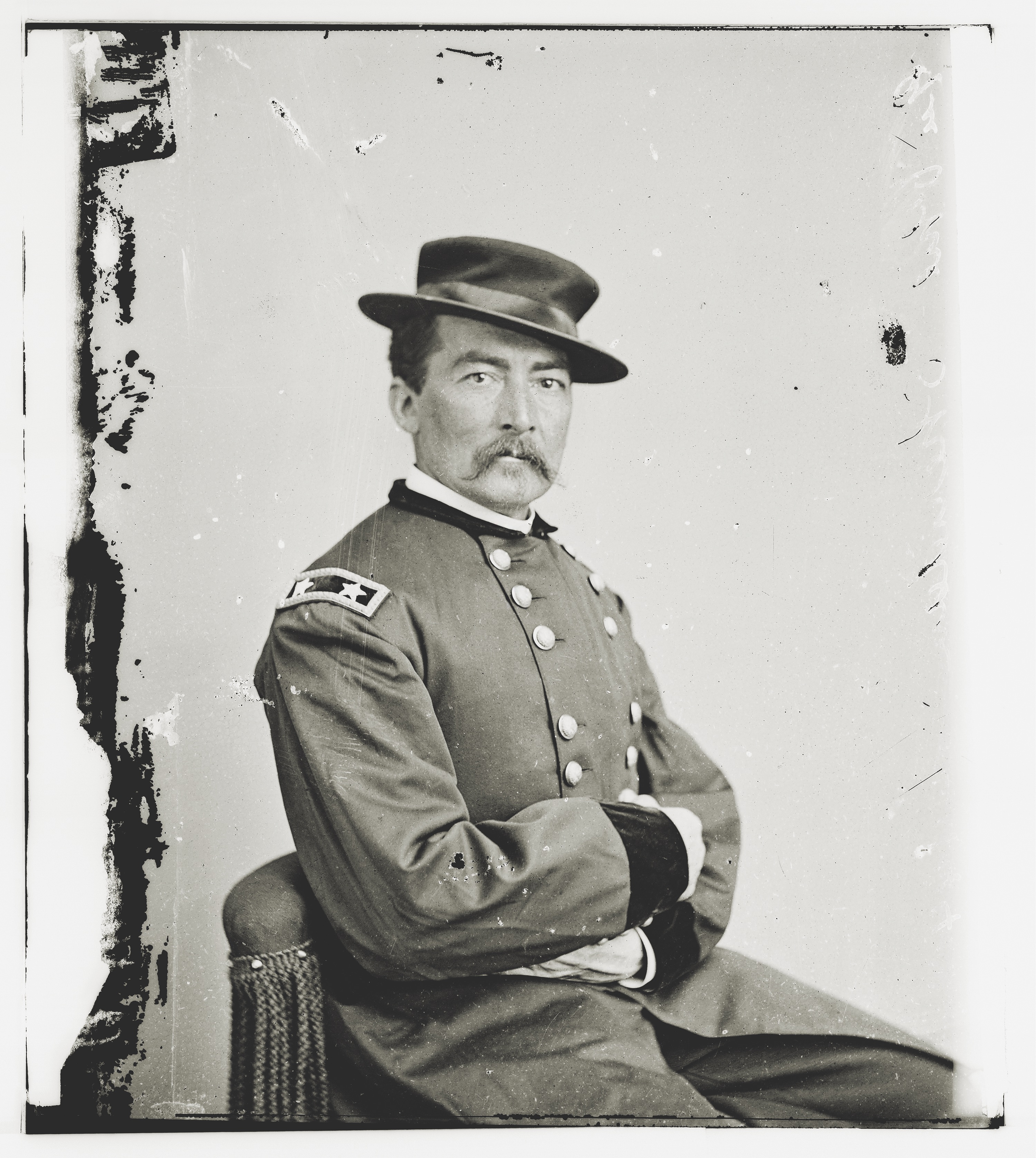

What about Sheridan’s testimony? In 1878, James E. Kelly, a sculptor and illustrator, interviewed Sheridan, at one point referring to the meeting between Grant and Lee. “Wouldn’t there be any way of showing you in the scene?” asked Kelly. “I would like to be in the picture,” responded Sheridan, “but I was not there.” He had accompanied Grant to McLean’s house, and “General Grant introduced me with other officers. I gave General Lee some papers referring to some of his men, firing on our Flag of Truce in the morning.” But then Sheridan, who was exhausted, excused himself, “went outside and laid down under a tree—although it was raining, I fell fast asleep, but hearing a noise I woke up and saw General Lee coming out of the door.” Kelly subsequently left Sheridan out of his sketch of the officers in McLean’s parlor—a sketch Ely Parker pronounced satisfactory.

Sheridan also wrote about Appomattox in his memoirs, published posthumously in 1888. He included Ord among the Federal officers who first saw Lee in McLean’s house. “After being presented,” observed Sheridan, “Ord and I, and nearly all of General Grant’s staff, withdrew to await the agreement as to terms, and in a little while Colonel Babcock came to the door and said, ‘The surrender has been made; you can come in again.’” Reentering the room, Sheridan observed Grant writing and soon spoke with Lee about the violation of a truce earlier in the day. “I am sorry,” Sheridan quoted Lee as saying, “It is probable that my cavalry at that point of the line did not fully understand the agreement.” Neither of Sheridan’s accounts mentioned Marshall, sitting on a sofa, or anything about rations.

These sources support different scenarios. Sheridan met Lee in McLean’s parlor but left before negotiations began; or was present early, departed, and returned after terms had been agreed upon; or left but returned in time to witness some of the proceedings; did or did not speak with Marshall and Lee and discuss rations. The particulars of Sheridan’s activities, though ancillary to the main story, remind us that recovering the past is an uncertain project. ✯