The senator began his interrogation with an innocuous question: “Where is your present residence?”

“Lexington, Virginia,” the witness replied.

“How long have you resided at Lexington?”

“Since the first of October last—nearly five months,” said the witness, whose name was Robert E. Lee.

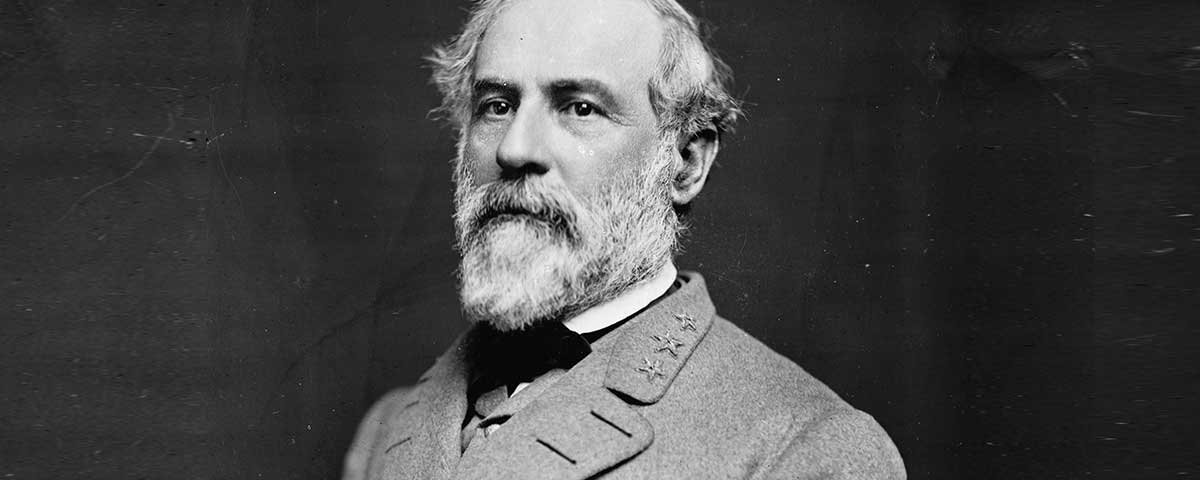

Lee had surrendered his Confederate army at Appomattox 10 months earlier, in April 1865. In the fall he became president of Lexington’s Washington College. Now, on February 17, 1866, he was in Washington, D.C., testifying before Congress’ Joint Committee on Reconstruction. He was not happy to be there. Even in the best circumstances, Robert E. Lee didn’t enjoy public speaking, and these were hardly the best circumstances. The Confederacy’s most famous general had been summoned to the Union capital to be grilled by a committee dominated by Radical Republicans determined to publicize evidence of atrocities committed by former Confederates against freed slaves and pro-Union Southerners.

“Are you acquainted with the state of feeling among what we call secessionists in Virginia at present toward the government of the United States?” asked Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan.

“I do not know that I am,” Lee replied. “I have been living very retired and have had but little communications with politicians. I know nothing more than from my observation, and from such facts as have come to my knowledge.”

“From your observation,” Howard said, “what is your opinion as to the feeling of loyalty towards the government of the United States among the secession portion of the people of that state?”

“So far as has come to my knowledge,” Lee replied, “I do not know of a single person who either feels or contemplates any resistance to the government of the United States or indeed any opposition to it.”

“How do they feel,” Howard asked, “in regard to that portion of the people of the United States who have been forward and zealous in the prosecution of the war against the rebellion?”

“Well, I do not know,” Lee said. “I have heard nobody express any opinion in regard to it. . . . I have heard no expression of sentiment toward any particular portion of the country.”

Really? Was it possible that the general had never heard anybody in Virginia express any opinion about Yankees in the first 10 months after the Civil War?

Perhaps Lee’s famously patrician bearing and gentlemanly manners discouraged his acquaintances from making rude comments about their former enemies. Or perhaps the general was being less than candid in his testimony. He certainly affected an air of ignorance that seems dubious, answering question after question with such phrases as “I never heard anyone speak on that subject” and “I cannot speak with any certainty on that point” and “I have no means of forming an opinion” and “I scarcely ever read a paper.”

When Lee repeatedly denied that former Confederates disliked Yankees, a skeptical senator asked: “Do you mean to be understood as saying that there is not a condition of discontent against the government of the United States among the secessionists generally?”

“I know of none,” Lee replied, apparently with a straight face.

As one of Lee’s biographers, Roy Blount Jr., put it: “Called before the congressional Reconstruction committee, Lee managed coolly to avoid giving Republicans anything regarded, at the time, as red meat.” But Lee’s awkward encounter with the committee was not simply a series of artful evasions. The general did reveal his views on several important issues, including racial equality and the meaning of treason.

“General, you are very competent to judge the capacity of black men for acquiring knowledge,” said Senator Howard. “I want your opinion on that capacity, as compared with the capacity of white men.”

“I do not know that I am particularly qualified to speak on that subject,” Lee replied. “But I do not think he is as capable of acquiring knowledge as the white man is.” Black people are “an amiable, social race,” Lee told the committee. They will work briefly to earn their sustenance, but they aren’t inclined to prolonged hard work: “They like their ease and comfort.”

Congress was debating a constitutional amendment granting black men the right to vote, and Representative Henry Blow of Missouri asked Lee his opinion of the idea.

“My own opinion is that, at this time, they cannot vote intelligently,” Lee said, “and that giving them the right of suffrage would open the door to a great deal of demagogism.”

“Do you not think,” Blow asked, “that Virginia would be better off if the colored population were to go to Alabama, Louisiana or some other Southern state?”

“I think it would be better for Virginia if she could get rid of them,” Lee replied. “That is no new opinion with me. I have always thought so, and always been in favor of emancipation—gradual emancipation.”

Lee’s views seem shockingly bigoted today, but in 1866, they were, as Blount wrote in his biography, “pretty much the genteel opinions of the time, North and South.”

More interesting than Lee’s racial views were his opinions on an issue that could have led to his execution—treason. The Constitution states, “Treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” Many Northerners felt that Lee—who had resigned from the U.S. Army to lead an army fighting against the United States—should be hanged for treason.

Nobody on the committee had the guts to ask Lee if he had committed treason, but Senator Howard backed into the topic, bringing up Jefferson Davis, the former Confederate president, who was then in prison awaiting trial. Would any Virginia jury, Howard asked, convict Davis of treason?

“I think it is very probable that they would not consider that he had committed treason,” Lee replied.

“In what light would they view it?” Howard asked. “What would be their excuse or justification?”

“So far as I know,” Lee said, “they look upon the action of the State, in withdrawing itself from the government of the United States, as carrying the individuals of the State along with it; that the State was responsible for the act, not the individual.”

“State, if you please,” Howard said, “and if you are disinclined to answer the question, you need not do so—what your own personal views on that question were.”

“That was my view,” Lee replied, “that the act of Virginia in withdrawing herself from the United States, carried me along as a citizen of Virginia, and that her law and her acts were binding on me.”

“And that you felt to be your justification in taking the course you did?” Howard asked.

“Yes, sir,” said Lee.

In the end, of course, neither Lee nor Davis nor any other Confederate was ever tried for treason. And Lee’s hour on the committee’s witness stand turned out to be the only time he was ever asked to explain his actions under oath. He came away unscathed, but he was no doubt delighted to return home to Lexington, where—if his testimony can be believed—nobody ever raised any disturbing questions about the Civil War.