U.S. Army Capt. Larry Thorne had just arrived at the Chau Lang Special Forces camp in South Vietnam’s Mekong River Delta in early 1964. The Green Beret, a member of the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne), reported for duty, stowed his gear and grabbed binoculars to study the terrain around the base. Thorne noticed something on a nearby hill: a Viet Cong flag blowing in the breeze above the dense tropical jungle. The captain set down his binoculars and called for volunteers to join him on a mission. The men silently crept around enemy positions to reach the VC site, where Thorne ripped down the flag and stuck it in his backpack. He would not allow the enemy to flagrantly display its colors in sight of his base.

That was pure Thorne (pronounced THOR-nee). A warrior in in the classic sense. He lived for battle and prepared endlessly for combat.

“He was physical, he was smart, but he was also unorthodox,” says biographer J. Michael Cleverley, author of Born a Soldier: The Times and Life of Larry Thorne. “He had a very John Wayne-esque personality”—not what you would expect someone to say admiringly of a man who served as an officer in the Waffen SS, the Nazi Party’s combat force.

But the native of Finland, an expert in guerrilla warfare and astute analyst of military intelligence, made a journey from World War II Europe to Cold War Vietnam that paralleled the one taken by the United States, which welcomed him into the fight against a new foe, in part through the personal lobbying of the former spymaster who ran the agency that spawned the CIA.

Larry Thorne was born Lauri Alan Törni (TOUR-nee) on May 28, 1919, in Viipuri, Finland. He grew up on Finland’s border with the newly minted Soviet Union in a family that was staunchly anti-communist.

At an early age, Törni became fascinated with a local garrison. He was “war-crazy, even before he was as high as a rifle,” his father told a Finnish author writing a biography of his son. “He was born to be a soldier.” Törni was drafted into the Finnish army in 1938, as tensions were escalating between the Finns and Soviets. He was assigned to the 4th Independent Jäger Infantry Battalion, an elite unit that supported other forces at crucial moments during combat. Törni’s abilities were soon recognized by his superiors, who sent him to noncommissioned officer school. He graduated as a mess sergeant.

On Nov. 30, 1939—shortly after Nazi Germany’s September invasion of Poland sparked World War II—Finnish-Soviet animosities flared into a side war when the Soviet Union launched an invasion over a territorial dispute.

In what was called the Winter War, the young army cook soon demonstrated that he was a fighter. When the 4th Jäeger was facing repeated Soviet attacks and casualties were depleting the battalion’s ranks, Törni volunteered to lead patrols against the enemy.

On Jan. 8, 1940, he was blooded for the first time. Törni led an assault through deep snow against a Soviet position. His unit blew up a truck and bunker while also taking out several enemy foxholes with grenades and submachine guns. The surprise attack succeeded without a single Finnish casualty. Törni’s bravery and daring leadership earned him an invitation to officers training school, where he was when the Winter War ended on March 13, 1940, with a peace treaty that gave the Soviet Union substantial chunks of Finnish land.

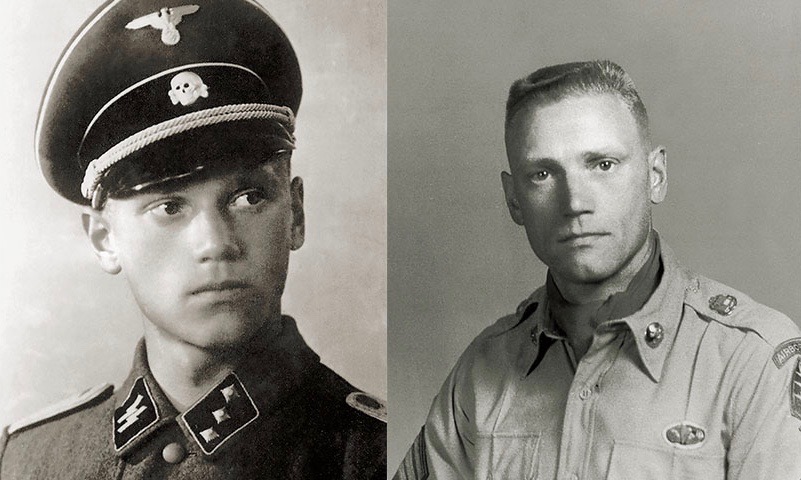

Finland sided with Germany during World War II because of their common enemy: the Soviets. The Nazis wanted Winter War veterans to volunteer for the Waffen SS and fight on the Eastern Front, and Törni was part of a 1,400-man Finnish force that signed up for German training. He was recognized as an SS Untersturmführer (equivalent to a second lieutenant).

Törni joined the Waffen SS to get the training and continue fighting the Soviet communists, Cleverley says. There is no evidence that he espoused Nazi views, according to the biographer.

Törni received seven weeks of SS instruction and returned to Finland when Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. He excelled in command of a Finnish guerrilla force—unofficially “Detachment Törni”—that harassed enemy units throughout this second round of Finnish-Soviet fighting, known as the Continuation War. He was so successful that the Soviets placed a reward of 3 million Finnish marks on his head—dead or alive. No Finns ever attempted to cash in on the offer.

For his “exceptional valor,” Törni was awarded the Mannerheim Cross of Liberty, the Finnish equivalent of the Medal of Honor. He was named a Knight of the Mannerheim Cross, one of only 191 men to receive that distinction. The commendation cited his “natural leadership talent” and used several pages to list his accomplishments in two wars. At least twice, it referred to Törni as “cold-blooded.” His service in the SS also was rewarded with Germany’s Iron Cross, presented for bravery and military leadership.

The Continuation War ended in September 1944 with an armistice after the Soviets decided they could not conquer Finland while still battling the Nazis, although the Soviet Union essentially kept the territories it got in the 1940 Winter War treaty. Even though Finland was ready to stop fighting, Törni was not. He joined Sonderkommando Nord, a paramilitary unit of Finnish nationals operated by the Gestapo, the Nazi government’s secret police.

Törni and a group of fellow Finns underwent intensive training in Germany in early 1945. However, it was becoming clear that the Nazis would lose the war. In addition, Törni had become disenchanted with the Germans and told his countrymen they had been deceived. He decided to desert and return to Finland.

At the end of World War II, a pro-Soviet government was installed in Finland. Törni was arrested and charged with treason

for serving in the Waffen SS. He was found guilty and sentenced to six years in prison. He escaped and was recaptured multiple times. Törni had served only one year when he was pardoned in 1948 by a new president.

In 1950, Törni moved to a Finnish community in Venezuela. He got a job on a freighter carrying ore to U.S. ports on the Gulf Coast. Once the freighter was in Mobile Bay, Alabama, Törni jumped ship—literally, by diving into the water and swimming ashore. He wanted to get to America and once on land would figure out how to stay there, a goal complicated by the fact that he didn’t speak English. (Over time he did learn the language but occasionally struggled with some of its complexities.)

Törni reached out to Alpo Marttinen, who had been one of the most highly decorated Finnish officers in World War II and was now in the U.S. Army. Marttinen worked behind the scenes to get Finns to the United States and serve with him under a new flag. Informally, they were known as Marttinen’s Men.

William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the founding director of the CIA’s predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services, in 1942 and now a partner in a law firm, was approached by Finnish American leaders to help their countryman, who had been arrested by the FBI for entering the United States illegally. Donovan used his connections to get Törni released.

However, the Finn’s Nazi past was still an issue. Törni used a knife to cut out a piece of his left arm that bore a Waffen SS tattoo indicating his blood type. The U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service was starting the deportation process when Donovan interceded again. This time his law firm lobbied Congress to pass a bill that would grant the Finn legal status. The legislation, signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on Aug. 12, 1953, stated that Törni was “considered to be lawfully admitted to the United States for permanent residence.”

Now known as Larry Thorne, the new U.S resident joined the Army on Feb. 1, 1954. At 34, Thorne was starting his military career over as a private in the 77th Special Forces Group (Airborne). His abilities were quickly noticed, however, and he was accepted for Officer Candidate School. Thorne was commissioned a first lieutenant in January 1957. He was promoted to captain in 1960 and assigned to the 10th Special Forces Group in Germany.

While there, Thorne led a select team on a mission to recover bodies and classified equipment from an Army U-1A Otter transport plane that went down in bad weather in January 1962 and crashed in the Zagros Mountains of Iran, near the Soviet border. Several rescue missions had already failed, but the Army wanted to bring back the remains of its soldiers and prevent the Soviets from obtaining classified equipment.

In June 1962, Thorne and his men climbed the treacherous mountain—through 18 feet of snow in places—found the bodies, retrieved the sensitive gear and destroyed what was left of the plane. Thorne was highly commended for his actions.

“He was a very astute and direct leader,” said Clyde Sincere Jr., a retired Green Beret major who served with Thorne at the Special Forces base in Bad Tölz, Germany.

During a training exercise at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, in August 1963, Thorne played the “rebel leader” of an insurgent group battling the 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions. He called himself “Charlie Brown,” for the lead character in the Peanuts comic strip, and wore a red scarf around the streets of local towns where the mock exercises were held. Though greatly outnumbered, his small unit successfully eluded both divisions and launched numerous attacks against them. Thorne even created a civilian auxiliary force to supplement his 45-man operation. All the while, he talked to local media covering the exercises and explained how he could use hit-and-run tactics to strike at will against a much larger force.

His superiors were impressed. “This tremendous effort on the part of Capt. Thorne provided a realistic ground environment for the conduct of Red Unconventional Warfare operations,” wrote one commander, who recommended “Charlie Brown” for the Joint Services Commendation Medal.

Thorne served two tours in Vietnam, the first during January-June 1964. Instead of fighting in snow and ice, this time he was doing battle in jungles with dripping humidity. But the same tactics applied.

Thorne led a variety of missions in Vietnam: search and destroy, counterinsurgency, base defense, infiltration and ambushes. He succeeded at everything. Though a tough and relentless officer, his men loved him and trusted his instincts. He seemed to have an uncanny knack for knowing what was going to happen next, skillfully analyzing field intelligence to thwart surprise attacks and being ready with a backup plan if the mission ran into trouble.

“Thorne was very meticulous as a commando leader,” Cleverley said in an interview. “He didn’t go into an operation thinking everything would go well. He spent weeks planning every single detail.”

Thorne was glad to be fighting the communists again. He knew well their oppression of others and had an intense dislike for them. Over time, though, Thorne developed reservations about America’s involvement in the war, according to Green Beret colleagues who talked to Cleverley. “What the basis of his thoughts was, I don’t know,” the author said. “Perhaps the idea behind the war, perhaps the way Washington was executing the war, or both.”

After his time at Chau Lang, Thorne moved to a camp at Tinh Bien, also in the Mekong Delta, along South Vietnam’s border with Cambodia. The camp was still under construction and vulnerable to attack. Thorne devised a plan to buy more time for the construction work by dealing a blow to the Viet Cong who were amassing a battalion to attack Tinh Bien.

Across the Mekong River in Cambodia was a detachment of Khmer Kampuchea Krom, a Cambodian force that had battled the South Vietnamese in the mid-1950s over land once belonging to Cambodia. Some Khmer Krom were now working with U.S. Special Forces to defeat the Viet Cong. But Thorne did not like this particular detachment, which operated as a bandit unit. It had recently beheaded seven Buddhist monks.

Thorne decided to put the Khmer Krom group in a trap and ordered it to scout an area on the Cambodian side of the Mekong to the rear of the Viet Cong.

On the Vietnam side, Thorne and a small force assaulted the VC in the staging area and pushed them across the river into Cambodia—right into the Khmer Krom. As the Viet Cong and Khmer Krom units began fighting each other, Thorne’s team and 100 allied fighters on the Cambodian side at the rear of the Krom attacked simultaneously, crushing the Viet Cong and Khmer Krom forces between them in a withering firefight.

A few days later, after the Tinh Bien camp was completed, a Viet Cong attack was expected. Thorne knew the enemy was infiltrating his position, but he could do little to prevent it. However, he secretly positioned mines at his own machine gun sites so that the detonations would kill infiltrators who reached the guns but not destroy the weapons. Sure enough, when the Viet Cong attacked and overran some America positions, they turned the machine guns toward the camp’s interior and began firing on the Green Berets and South Vietnamese soldiers. Thorne reached for his detonator and set off the explosives. His troops ran to the machine guns and soon had them back in action against the Viet Cong.

Despite all the preparation, Tinh Bien was almost overwhelmed by the larger enemy force. Thorne called in an airstrike by U.S. Air Force T-28 Trojan attack planes, which dropped napalm and strafed the VC with .50-caliber machine guns. The attack was broken, and the base held.

Thorne began his second Vietnam tour in February 1965 as an intelligence officer with 5th Special Forces Group. He organized and coordinated multiple missions for five reconnaissance teams. Working closely with operatives on the ground to monitor enemy movements, Thorne again anticipated the enemy’s intentions—an attack on Nha Trang air base on the coast in central South Vietnam.

Col. J. M. Spears, commander of the 5th Special Forces Group, lauded Thorne’s intelligence work in an Officer Efficiency Report: “Thus far in Vietnam, there has been only one Viet Cong attack on a major U.S. installation in which the enemy did not achieve surprise. This one instance was the attack of Nha Trang airbase on 25 June in which damage was minimized because the prompt response of defense elements disrupted the Viet Cong effort. It was Captain Thorne’s work that made this action possible.”

Thorne then transferred to MACV-SOG, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam-Studies and Observations Group, a classified highly secret organization of elite troops that included Army Green Berets, Navy SEALs and Air Force special operations teams that conducted reconnaissance missions, raids and a variety of other covert activities.

Thorne’s last action occurred on Oct. 18, 1965, during the secret Operation Shining Brass in Laos. The plan called for SOG Recon Team Iowa, flying in a Sikorsky CH-34 helicopter of the South Vietnamese air force, to be dropped off along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and search for enemy supply dumps that could be bombed later by aircraft. Because of reports of heavy enemy activity in the area, Thorne accompanied the recon team in a second South Vietnamese CH-34, a command helicopter that would return to base as soon as he received a safe-insertion signal from the men on the ground.

Just as the recon unit landed and disappeared into the jungle, the weather closed in on the command helicopter. Heavy rain and dense clouds enveloped Thorne and the crew of three South Vietnamese airmen. While other nearby helicopters departed the terrible storm, the Special Forces captain hovered overhead until he was sure his team was safely in position to begin its mission.

Finally, Thorne received the signal, and his helicopter began to leave the area. It fought intense squalls and zero visibility. Thorne radioed the base several times. Then there was silence from his helicopter. Thorne was reported as missing that day. More than 50 search-and-rescue missions were flown, but no crash site could be found.

Recon Team Iowa did not learn of its commander’s death until the men returned to base. The unit’s mission was a success. It had identified scores of enemy stockpiles, which were destroyed by dozens of air sorties. The first assault of Shining Brass was an important victory—but it came at terrible cost.

Thorne was declared killed in action a year later and posthumously promoted to major. Because of the commander’s seeming invincibility, many of his comrades refused to believe he was dead. Rumors floated for several years that he was still alive, but no sightings were confirmed.

In the summer of 1999, a Defense Department task force established to locate missing service members received permission from the Vietnamese government to search a site believed to be the place where Thorne’s helicopter went down. There, on a steep slope of a jungle-covered mountain, were the remains of several individuals killed in an apparent chopper crash. Subsequent DNA testing revealed Thorne’s remains were among them. He was 46 when he died.

On June 26, 2003, Thorne and three South Vietnamese crewmen were buried in a single coffin at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. During his two tours in Vietnam, Thorne received the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Bronze Star Medal and two Purple Hearts. He was nominated for the Silver Star.

In novelist Robin Moore’s The Green Berets, a thinly veiled portrait of the Special Forces in Vietnam published in May 1965, the character called “Korni,” a hard-fighting officer who leads successful missions against the Viet Cong, is based on Thorne. In the 1968 John Wayne film inspired by the book, one scene closely resembles Thorne’s actions with the land-mined machine gun sites at Tinh Bien.

Today the Green Beret is remembered in the name Thorne Hall, the 10th Special Forces Command Headquarters building at Fort Carson, Colorado. He is enshrined in the U.S. Special Operations Command Commando Hall of Honor at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida.

Thorne also is revered in Finland, says Cleverley, who learned about him while stationed there with the U.S. Foreign Service. His book, published in 2003, was a No. 1 nonfiction seller in Finland. “From what I know of Thorne, he didn’t have a lot of respect for the Vietnam War, but he was willing to fight for it and give his life for it,” Cleverley said.

Each summer, the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) honors its most outstanding soldiers with the Thorne Award for Excellence.

“Larry Thorne embodies what the Special Forces was intended to be,” said Col. Lawrence G. Ferguson, the group’s current commander. “We are supposed to go into other cultures, live there and wage war there. That is our mission, and Thorne did it as few others have.”

David Kindy is freelance feature writer who lives in Plymouth, Massachusetts. He frequently writes about military history, especially the men and women who served in America’s wars.