In war some cities fall in battle, others by starvation. But in early August 1964 Stanleyville—present-day Kisangani, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo—fell to black magic. From the windows of the U.S. Consulate on Avenue Eisenhower the few Americans who hadn’t evacuated were astounded to see their ostensible protectors in the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC) desert their posts and flee. Moments later a bare-chested witch doctor walked up the street, chanting and waving palm branches to sweep the city of government troops—and it worked. Some 1,500 soldiers threw down their rifles, machine guns and mortars and abandoned Stanleyville to a mere 300 warriors armed with little more than spears, bows and hoodoo.

It was the Americans’ first glimpse of a Simba (“lion” in Swahili), one of the fearsome communist Congolese rebels who—made brave by dagga (cannabis) and faith in dawa (magic they were told would turn enemy bullets to water on contact)—that summer had conquered an area the size of France. They proceeded to terrorize Stanleyville’s 300,000 Congolese residents and round up American and Belgian diplomats, missionaries, nuns, businessmen and their families—nearly 2,000 all told. As hostages the whites would become pawns in a Cold War gambit played out in the dark heart of Africa.

In the Congolese capital of Léopoldville (present-day Kinshasa) 45-year-old Thomas Michael Hoare—former British officer, safari operator, accountant and soldier of fortune—was summoned to meet with Congolese leader Moïse Tshombe and ANC commander Maj. Gen. Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. Three years earlier Tshombe, then president of the breakaway province of Katanga, had fought Mobutu’s forces to a draw. Under Tshombe’s hire at the time, mercenary captain Hoare had run a truck convoy 840 miles through hostile jungle to resupply a rebel garrison. No sooner had it arrived, however, than United Nations peacekeepers received orders to arrest all mercenaries. Hoare and his commandos fled into the jungle, in the process losing two men, who were captured by locals, ritually tortured and killed. The rebellion ultimately collapsed. Tshombe and Hoare were both expelled. Katanga was not a fond memory.

But everything was different this go-around. The U.N. was gone. With Mobutu’s backing, Tshombe was the Congolese prime minister, and he wanted to rehire Hoare—this time to fight for the Congo against the Simba rebels.

Problem was, the top mercenary markets were Rhodesia and South Africa, apartheid nations scorned by black Africa. Paying white men to shoot black people was taboo; the mercs in Katanga hadn’t acquired the nickname les affreux (“the dreadful ones”) by accident. But Tshombe didn’t care where such troops came from or what color they were. “I see the problem a thousand times clearer than all my African critics think they see it,” he told Hoare. “Our beautiful country should not become hostage to a pack of bandits.”

Mobutu was not so keen on the idea.

“I sensed then that he resented my presence…a foreign element called in to do the job the ANC had shown themselves incapable of doing,” Hoare later wrote. “I could see that our relationship would have to be handled tactfully.”

His employers promoted Hoare to major (his former rank in the British army) and authorized him to raise a new command and retake Stanleyville. Classified ads in the Salisbury and Johannesburg newspapers, however, drew as much riffraff as military material. “Few of the rank and file had military training,” mercenary Ivan Smith remembered, “and no discipline was enforced. The sergeants and officers were barely better trained.” A venturesome 22-year-old who had done his stint as a Rhodesian army reservist, Smith thought little of officers, including his new commander, but had to admit, “Hoare had a natural commanding manner, one that induced obedience in any trained soldier.”

Hoare’s unit, 5 Commando, moved into a huge Belgian-built, NATO-funded military base at Kamina, in Katanga Province. Hoare recalled “long days beginning at 5 in the morning and ending at 10 at night, when my greatest ambition was to weld a little unit together that we could be proud of and to see it properly armed, trained and equipped.” An Irishman by heritage, he nicknamed them the “Wild Geese,” after the Irish mercenaries who had fought across Europe in the 16th–18th centuries.

Needing a public relations triumph as much as a military victory, Hoare aimed to rescue some 130 Belgian hostages in Albertville (present-day Kalemie), on the western shore of Lake Tanganyika. At the prospect of actual combat, however, some of his men threatened to quit. “I realized that this is the moment in the life of every commander when his authority is challenged,” he recalled, “and everything stands or collapses from his instant reaction.” He pistol-whipped the lead mutineer. The rest promptly obeyed. Hoare called it “a watershed in my life.…Without it I could never have done my duty or lived through the horrors which were to be my lot.”

Battling heavy chop and balky outboards, 5 Commando boated up the lake only to stumble directly into Albertville’s Simba garrison and withdraw with two dead, seven wounded and no hostages. The lesson was not lost on Hoare. “It had been an error to try them so highly so soon,” he admitted of his troops. “No man henceforth would see battle until he had received a thorough basic training.”

But in Stanleyville the clock was ticking. The Simbas had publicly executed 137 Congolese for their European sympathies. The worst of the lot were the jeunesse, gangs of ruthless street youths who delighted in rape, flaying, burning, impalement, dismemberment, disembowelment, even ritual cannibalism. For the time being the white hostages were worth more as live bargaining chips than as dead amusements, but no one knew how long that would last.

As additional recruits arrived in Kamina, Hoare split 5 Commando into sub-commandos—numbered 51 through 57, with 30–40 troops each—and deployed them across the Congo. Lt. Garry Wilson—a 25-year-old Sandhurst-educated South African and veteran of the Royal Horse Guards during the late 1950s Cyprus Emergency—drew first blood with 51 Commando in Lisala, on the Congo River some 350 miles downstream from Stanleyville. “The rebels were on a hill about 200 yards away, firing wildly with machine guns and a bazooka,” he told a New York Times reporter. “We had only automatic rifles.” At the first shots their ANC backup bolted into the bush, leaving Wilson with just 42 mercs, of whom only 15 had combat experience, to face 400 Simbas. “They were in the open with no cover,” the lieutenant recalled. “They have no fear of death. We just walked slowly up the hill, firing as we went. It was like a shooting gallery.” He personally shot 13 rebels before he stopped counting. When the mercs had killed some 150 rebels, the rest vanished into the jungle, along with one-third of the ANC troops. One mercenary was slightly wounded.

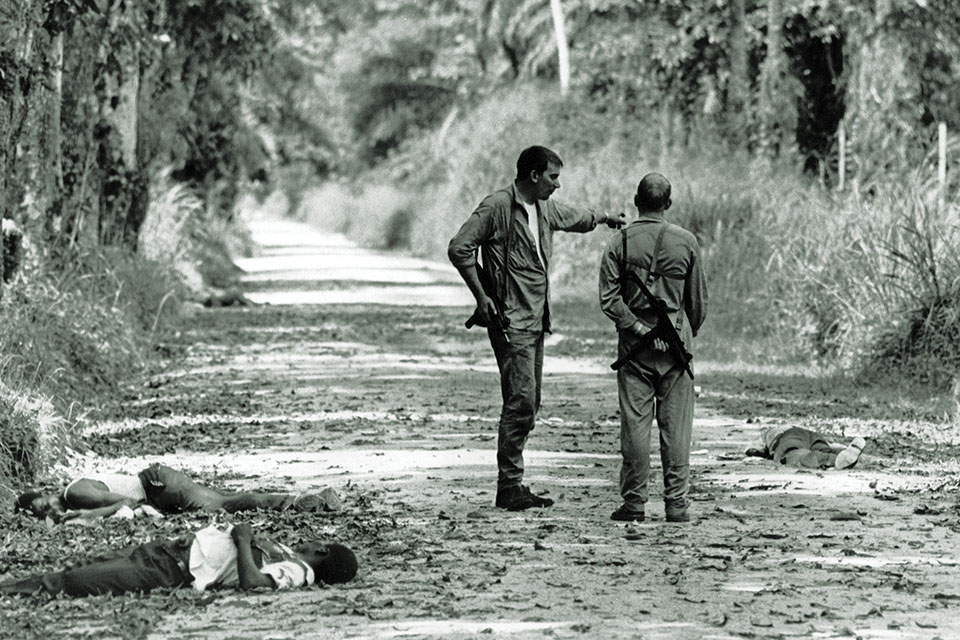

The Wild Geese then got their first glimpse of real African warfare: ratissage (French for “raking”), characterized by ritualistic, tribal revenge. The Congolese had no regard for chivalry or mercy, nor any squeamishness about inflicting pain. “All day and night gunfire rattled,” Smith remembered, “and screams of tortured men and women filled the air.” To stop the killing, the mercenaries finally ran off the ANC, much as they had the Simbas. “That day we finally learnt the Congolese army was in dreadful, awed fear of the mercenaries.”

Savagery wasn’t exclusive to the natives. Pushing toward Stanleyville from the west, 52 Commando—with a large contingent of German ex-paratroopers—was led by Capt. Siegfried Müller, a former Wehrmacht sergeant on the Russian front. “Prussian as a Pickelhaube,” Hoare recalled of the captain, whom he permitted to wear an Iron Cross, complete with swastika. Müller’s mercs decorated their vehicles with captured spears, shields and the heads of dead rebels. Belgian Lt. Charles Masy was photographed cleaning skulls for sale as souvenirs—a coup for communist propaganda. “Kongo Müller” himself was unwittingly featured in an East German propaganda film. “I learned from the press that I was a war criminal, an SS veteran, that…I was carrying a copy of Mein Kampf, which I read after each battle,” he recalled. “Oh, it was black times!”

All the mercenaries’ excesses would be forgiven if they could retake Stanleyville. The main thrust comprised more than 200 trucks and jeeps, armored cars abandoned by the U.N. in 1963, and an air force of vintage Douglas B-26 Invader bombers and North American T-28 Trojan trainers converted to fighters. Piloting the planes were CIA-backed, anti-communist Cuban exiles. On October 30 the Wild Geese boiled out like siafu, African army ants, on the road to Stanleyville, a 1,000-mile drive to the north. Hoare ordered his men to expend their plentiful ammo at will. “When we first went into action, we were trying to work as soldiers,” Smith said, “but in the end we just had machine guns mounted on Jeeps, and we’d scream along the road. If anyone approached us, we’d just open fire.”

The commandos closed on Stanleyville from three directions. Then, on the brink of total victory, came an order to wait: The Americans were attempting to negotiate with the Simbas for the hostages. Meanwhile, Belgian paratroopers had staged out of the British base on equatorial Ascension Island to Kamina, preparatory for an airdrop code-named Operation Dragon Rouge. “My solution to the hostage problem would have been the landing of an airborne battalion damn quick, regardless of the diplomatic niceties,” Hoare grumbled. “To halt at this moment when we were in striking distance of Stanley-

ville filled me with apprehension.”

Meanwhile, Radio Stanleyville whipped the Simbas into a blood frenzy: “Sharpen your knives! Sharpen your machetes! Sharpen your spears! If the paras drop from the sky, kill the foreigners. Do not wait for orders. You have your orders now: Kill, kill, kill!”

Needless to say, negotiations had failed. The Belgians would jump at dawn on November 24. At dusk the prior evening 5 Commando’s main column was still some 150 miles away. “I had impressed upon all ranks a hundred times the stupidity of moving by night through enemy- controlled territory,” Hoare recalled, “and here we were, about to do that very thing.” In darkness and pouring rain they ran a gantlet of Simba ambushes. “I salute every man who took part in that column that night. It was the most terrifying and harrowing experience of my life.”

Still on the outskirts of Stanleyville when word came the paras were dropping, the commandos made up for lost time. “As the convoy drove by at speed,” Smith remembered, “sections of paratroopers in foxholes at the side of the road waved, indicating and shouting that there were enemy ahead. They were visibly amazed when the mercenaries just waved back and drove on.…The speed of the convoy entering the city that morning was as a result of greed overcoming fear.”

Alerted and enraged by the sight of Lockheed C-130 Hercules transport planes and parachutes overhead, the Simbas had herded their hostages into the street. “Your brothers have come from the sky,” they taunted. “You will be killed now.” As the paratroopers closed in, the rebels suddenly cut loose with automatic weapons fire, killing some two-dozen men, women and children and wounding more than 50 others before the paras and mercs cleared the city.

“Now the sack of Stanleyville began,” recalled Hoare, who turned a blind eye as the mercenaries smashed store windows, drank hotel liquor stores dry, used dynamite and acetylene torches on bank safes and even released lions from the city zoo into the streets. “I know my men looted, but with the atrocities occurring all around me…I did not regard it as a shooting matter. Not after what I had seen.”

What he’d seen was the ANC’s vengeance, ratissage on a citywide scale. “I never saw such a bloodbath in my life,” said Belgian commander Col. Charles Laurent. “No prisoners were taken. They [the rebels] were shot up, cut up or beaten to death. It was brutal.” His work done, Laurent ordered his paratroopers back onto their planes, and they put Stanleyville behind them.

“The Belgian paras came, delivered and departed,” Hoare wrote. “We were now left to get on with it.” Over the next two days his mercenaries rescued more than 1,800 Americans and Europeans and 400 Congolese from around the city. “Taking Stanleyville was the greatest achievement of the Wild Geese. There is only so much a small unit of 300 men can do, but here we were part of a very big push, and clearing the rebels out of Stan was a major victory for our side.”

International reaction to the Stanleyville operation was swift and predictable. Mobs demonstrated outside the U.S. and Belgian embassies in Nairobi, Cairo and Moscow. Communist icon Ernesto “Che” Guevara addressed the U.N. to decry “Belgian paratroopers, carried by U.S. planes, who took off from British bases.” He embarked on a press tour of sympathetic African nations, with stopovers in Soviet Russia and Red China, and by early 1965 had infiltrated into the Congo to rally the Simbas into expanding the global communist revolution.

Hoare had seen enough. “I wanted no more of this damnable country,” he recalled. “My time in the Congo was up. I was a spent force.” Tshombe and Mobutu talked him into staying. After all, the real menace was not the Simbas, but their communist abettors. They promoted Hoare to lieutenant colonel and made his mercenaries the heart of Congo’s army. “I had wanted nothing so much as to have 5 Commando known as an integral part of the ANC,” Hoare admitted, “a 5 Commando destined to strike a blow to rid the Congo of the greatest cancer the world has ever known—the creeping, insidious disease of communism.”

With reports of the mercenaries preceding them, transmitted by jungle drum, Hoare in mid-March launched a successful land-water assault against rebel strongholds on the north shore of Lake Albert. His 5 Commando then struck out along the borders of Uganda and Sudan to cut Simba supply routes. When the rebels sought refuge across the borders, Hoare called on 57 Commando Capt. John Peters—either a veteran or deserter of the British Special Air Servicewho reportedly had once stabbed a Belgian for sleeping on his cot and shot a cook when he found a monkey hand in his soup. “Mad as a snake,”said Hoare, who sent him with 100 mercenaries 8 miles into Sudan to kill 80 rebels and burn their camp. He then promoted Peters to commandant. “There were some repercussions in the British Embassy,” Hoare recalled. He shrugged them off. East German radio began referring to him as “the mad bloodhound, Mike Hoare.”

Told it would take at least six months to subdue eastern Congo, Hoare resolved to do it in three days, starting with a veritable freshwater D-Day invasion of a rebel stronghold on the northeast shore of Lake Tanganyika. His assault fleet—six 21-foot powerboats, a 75-foot trawler and two 50-foot, radar-equipped, CIA-supplied Swift boats—shipped out after dusk on September 24 and by dawn on the 25th was moving up the middle of the lake out of sight of land. Two hundred men hit the beach up the coast but were pinned down for days before reinforcements could push through overland. “The ferocity of the enemy astounded us, and the strength of their forces far exceeded my estimation,” Hoare admitted. The rebel force comprised some 2,000 Congolese led by three-dozen Cuban advisers. “The enemy were very different from anything we had ever met before. They wore equipment, employed normal field tactics and answered to whistle signals. They were obviously being led by trained officers.” Radiomen overheard enemy conversations in Spanish until the fifth day, when the rebels reverted to type and obliged the mercenaries with a screaming mass attack. “We held our fire until they could receive the full benefit of every shot,” Hoare said. “They broke and fled, astonished that the bullets had not turned to water.” He realized the Cubans had pulled out.

Guevara later blamed his failure on the Africans. “They did not know how to handle their weapons and did not want to learn,” he grumbled, calling the average Congolese soldier “lazy and undisciplined…the poorest example of a fighter that I have ever come across.”

Hoare’s mercenaries, on the other hand, worked magic with Congolese troops. “Fear, the great equalizer,” he recalled, “had forged a new understanding in many of us, black and white.” As they mopped up eastern Congo together, Peters almost captured Guevara in camp, forcing the communists’ famed idol to effect an ignominious escape to Tanzania. In later years Hoare took pride in saying, “I was the only man known to have beaten him in battle.”

The mercenaries’ victory came at a political cost. Prime Minister Tshombe—too successful for his own good and thus deeply unpopular in much of the rest of Africa—was dismissed from office. In response, Mobutu staged a coup against the new regime. Hoare approved. “The army represented, in effect, the only system of administration which had shown itself capable of government,” he later explained. That was proven in 1967, when French and Belgian mercenaries led a mutiny in eastern Congo, and Mobutu ran them out of the country.

By then Hoare had long since handed over 5 Commando to Peters and returned home to South Africa. He served as technical advisor on the 1978 war film The Wild Geese (starring Richard Burton as a mercenary commander patterned after Hoare) and kept out of the fighting in Angola and Biafra. Around that time, however, he was contracted by exiles from the island Republic of Seychelles to stage a coup and in November 1981 flew into the capital with 40-odd mercenaries disguised as a rugby team. After an airport security supervisor discovered a disassembled AK-47 hidden in one of their flight bags, Hoare’s men produced weapons, sparking a six-hour gun battle, during which one merc and one soldier were killed. The cornered mercenaries ultimately hijacked an Air India 707 to South Africa. Hoare received a 10-year prison sentence but was released in 1985.

Mercenary warfare has since become big business, private military companies accepting lucrative contracts to fight worldwide, from the Balkans and South America to Afghanistan and Iraq. Meanwhile, by the turn of the century the Congo struggle had flared up into the Great African War, embroiling nine countries and some 25 factions, while displacing 2 million people and leaving another 5.4 million dead, making it the deadliest conflict since World War II.

“Even so, my basic views of mercenary soldiering have not changed,” reflects Hoare, who turned 99 on March 17, 2018. “I’m not going to apologize for being a hired soldier. Quite the contrary. I’m proud to be in charge of 5 Commando. I am proud to have fought shoulder to shoulder with the most courageous and determined people I have ever had the honor to command…the legendary ‘Wild Geese.’”

Don Hollway wrote “High Tide of Viking Ireland” (September 2018), about Irish defenders’ 11th century push to drive out Norse invaders. He thanks Chris Hoare, author of “Mad Mike” Hoare: The Legend, for his help in this article. For additional reading Hollway recommends Mercenary, by Mike Hoare; Mad Dog Killers, by Ivan Smith; and 111 Days in Stanleyville, by David E. Reed.