100,000 rushed to the Klondike, where border between Alaska and Yukon was mist on the tundra

[divider]

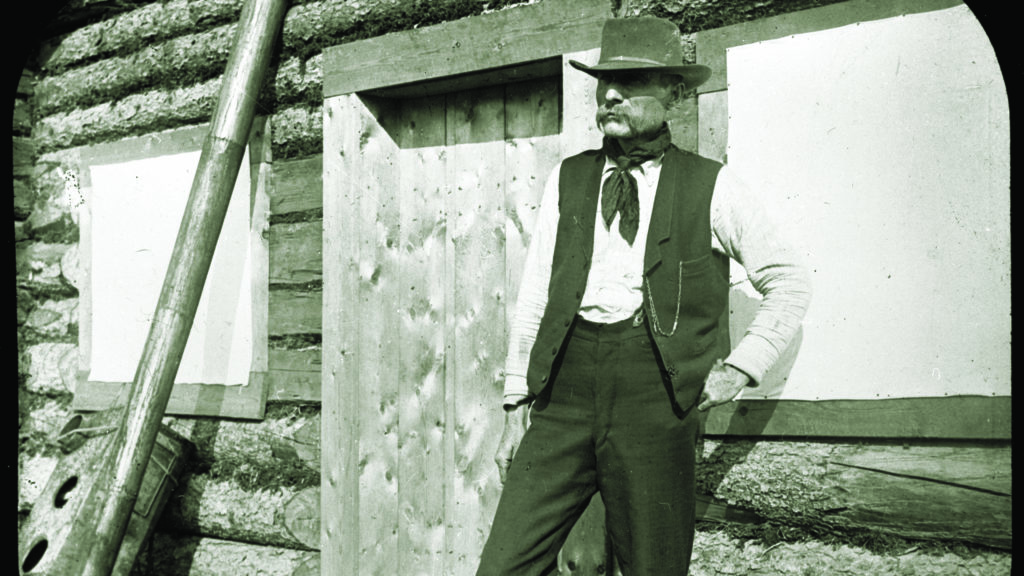

GEORGE CARMACK WAS one of those fellows whom poet Robert Service described as belonging to a “race of men who don’t fit in.” A U.S. Marine Corps deserter, Carmack was 22 when he wandered to Alaska in 1882. He wanted to go deep into the wilderness, but the Coast Range stood in the way—except at passes like Chilkoot, reached by a precipitous 3,057-foot climb that Carmack slogged as a porter, carrying freight on a path too steep for pack animals. From the far slope spread a vast space inhabited in 1882 by only 2,000 non-native men and women. Their camps and cabins dotted the Yukon River’s stream to the Bering Sea, 2,000 miles away. Soon Carmack was living among these rugged individualists, who called themselves “sourdoughs,” after the yeasty starter they carried to make bread for themselves in a land without stores. In those 330,000 square miles of wild, the lone trace of civilization was Fortymile, a smudge of a town near where the Yukon flowed into Alaska from Canada’s Yukon Territory. This corner of Canada east of the Coast Range was known as the Klondike—an Anglophone rendering of what indigenous people called the region.

[divider_flat]While many Americans in the lower latitudes had been heading west, a cantankerous few had reached the Pacific and turned north, drifting up to the flank of the Coast Range and crossing the mountains over notches like Chilkoot, White, and Chilkat passes and along rivers like the Stikine, in the territory’s panhandle, and the Copper, in central Alaska. Besides learning to trap, cure, and sell fur-bearing animals’ pelts, sourdoughs acquired the rudiments of gold prospecting. Few had any skill at the task, except for knowing the process of filing claims on spots where gold turned up. Staking a claim was simple, and literal. Finding gold, a prospector fashioned wooden poles, by regulation four feet in length, and staked out the corners of an area not to exceed 20 acres. The prospective miner then had to file a written description of the locale he was claiming at the land office, in this case in Fortymile—public notice that he declared that spot his own. A claim applied until a claimant ceased mining at the site. Local miners’ committees recognized and enforced claims.

In the wild, gold sometimes appears in its pure form as flakes that settle in streambeds. A deft hand with a shallow pan can use water to swirl away dross, leaving a sparkle. Gold can be embedded in quartz, accessible only by mining. In the Klondike, nuggets could be unearthed along a 700-mile stretch of the Yukon River in what geologists call the Tintina Gold Province, where erosion ground down an ancient mountain range.

Carmack lived off the land and for himself, trapping animals and occasionally finding small gold deposits. He sold pelts, nuggets, and dust to local trading posts. He married a Native woman named Kate. In August 1896—in the Klondike, August is autumn; winter starts in late September—he was living along the Yukon with Kate and brothers-in-law Skookum Jim and Tagish Charley. Gold was bringing $20.67 an ounce. As the four were fishing on Klondike Creek where it emptied into the Yukon, they came upon fellow sourdough Robert Henderson, who was hunting for gold on unclaimed land. Carmack, 36, asked Henderson how he was doing. Henderson had found a little gold, but told Carmack the pickings were slimmer than on Rabbit Creek, which flowed into Klondike Creek less than ten miles upstream from Carmack’s fish camp. Carmack moved his extended family to Rabbit Creek and set about prospecting. They came up dry until Skookum Jim, raising his rifle to shoot a moose, saw a flash in the water. Rabbit Creek, thickly forested on either bank, was laden with nuggets. Jim, Charley, and Carmack filled supply bags with gold. Carmack headed for Fortymile, 52 miles downstream, to file a claim and get a drink.

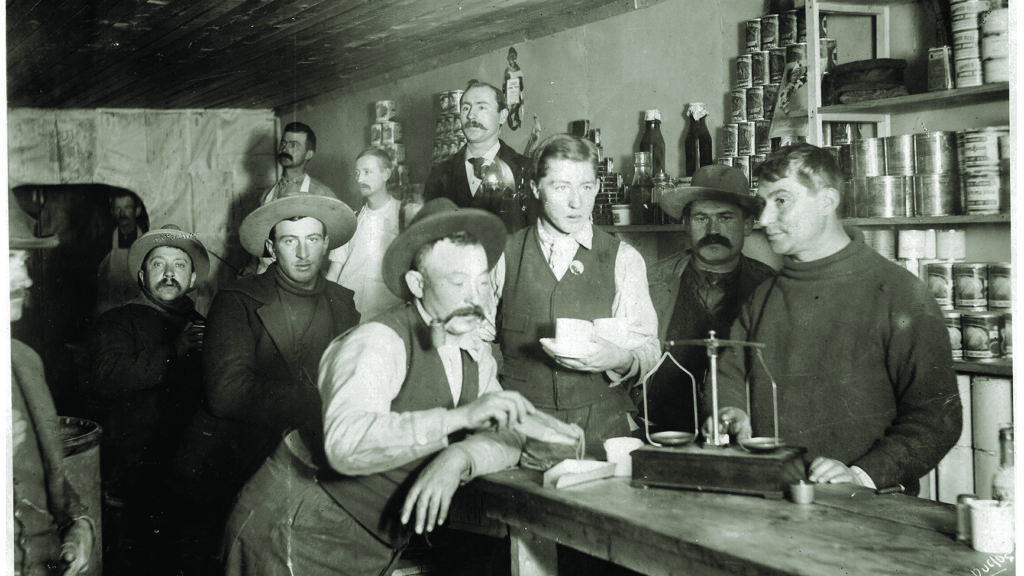

At Bill McPhee’s saloon, raving about his score, Carmack stood the house to a round. His companions were an odd lot. Four kept pet moose—in their cabins. Unable to afford dogs, Frank Buteau used a sail to propel his sled. Paddy Meehan had made himself dentures by shaping tin spoons to his gums, installing front teeth from mountain sheep in place of his own and molars from a bear he had shot as the predator was trying to get into his cabin.

Like Carmack, the gold bugs at McPhee’s had been chasing all over the Klondike for years. Recession-weary Americans saw gold as the only secure asset. High unemployment and distrust in banks, particularly a suspicion that establishment bankers—and the government—favored the Eastern Seaboard, inspired many Westerners to strike out for Alaska.

At McPhee’s, Carmack paid his tab in nuggets and left. Fortymile’s population moved to Klondike Creek, where a tent town bloomed. To serve its occupants, entrepreneurs founded a supply camp they called Dawson. Soon the banks of Klondike and and Rabbit creek were excavated to permafrost, the stratum of Yukon earth that never thaws. Creekside bonfires softened the ground enough for picks and shovels to hack free chunks of “muck”—an eons-old hard-frozen mix of humus and decayed vegetation that with the spring thaw would yield whatever gold it held. When winter clamped down in earnest in November, miners holed up. Their presence on Klondike Creek interested Canadian Northwest Mounted Police Inspector Charles Constantine, who commanded a small detachment at Fortymile. Noting that nearly all the miners at the strike were American—they claimed Fortymile was in Alaska, but in 1894 Constantine, shooting the sun, had determined the town to be in the Yukon, a finding confirmed by a surveyor—Constantine rode to the coast. From the Presbyterian mission settlement of Haines, he sailed south to Vancouver, British Columbia. He telegraphed his superiors in Ottawa, alerting them to the informal invasion. The spring thaw confirmed what Carmack’s initial strike had predicted and Constantine’s telegram implied. The ensuing gold rush brought the United States dangerously close to war with the British Empire.

The Klondike had neither telegraph lines nor roads, but ever since the Americans had bought Alaska from Russia in 1867 they had been studying the place. In 1884, a U.S. Army expedition led by Lieutenant William Abercrombie mapped the “All-American Route” to the Klondike. The map showed a path up the Copper River from the Gulf of Alaska to the Yukon

River. Only Abercrombie knew his report was a fake. The route he claimed to have mapped did not exist.

To reach the greater world, word of the Klondike strike had to wait until spring, when prospectors sailed the Yukon to the Bering seaport of St. Michael, Alaska, to board the southbound steamers Portland and Excelsior. On July 14, 1897, the Excelsior docked at San Francisco, disgorging gold-laden passengers. Within two days, alerted by telegram, 5,000 people were waiting at Seattle, Washington, as Portland, in its hold more than a ton of gold, tied up. Along the West Coast, anything that would float turned north, especially in Seattle, where hordes jammed the wharves. Store clerks quit. Streetcar operators retired mid-run. Gold bugs streamed into town, buying up gear and stealing dogs to smuggle north.

Taking the bogus Abercrombie map at face value, Klondike-bound prospectors traveled to what he had described as the trailhead to learn that there was no trail. A raggle-taggle town sprang up; today it is Valdez, Alaska. The phony map also flummoxed the U.S. Army until work began to break a trail, along which the Army built a series of forts from the coast to the Canadian border.

Seattle Mayor W.D. Wood was in San Francisco when Excelsior docked. He telegraphed his resignation from office, raised $150,000, and bought a steamer to take him and paying passengers to St. Michael. John McGraw, president of the First National Bank of Seattle, sailed to Alaska on Portland’s return voyage. So did a Seattle man dying of lung disease who from the gangplank shouted to relatives that he would rather die trying to get rich, thank you. Within months, 40 ships, some on the verge of being scrapped, had left for Alaska.

More than 100,000 people made for the Klondike—Wyatt Earp, boxing promoter George “Tex” Rickard, and other Western figures chasing a last hurrah, plus teachers, bank tellers, seamen, basketball coaches, and single mothers bringing children. Between spring thaw and autumn freeze prosperous prospectors could sail around Alaska to St. Michael and up the Yukon, but many more debarked at Alaskan panhandle ports Skagway and Dyea, nine miles apart and now jammed with transients staring at the granite mass of the Coast Range, ten to 20 miles inland. Skagway fed the Dead Horse Trail, a 20-mile march to White Pass. From Dyea new arrivals took the Chilkoot Trail, 15 miles to the pass of that name. Once over either pass, a Klondike-bound traveler had 600 miles to go. Traffic was mostly one way. A third pass, the 3,510-foot Chilkat, ran from Haines. However, the trail not only meandered 246 miles but was owned by one Jack Dalton. The Dalton trail’s length and the toll the owner charged discouraged its use.

In Skagway, a young opportunist named Jack London described tents, huts, and crude wood structures lining muddy streams functioning as streets along which whores worked in public. Laughter, screams, and gunfire filled the air. Murders occurred nightly. Dead Horse Trail, a series of switchbacks and so the less punitive route, got its name from the fate of pack animals succumbing to beatings, exhaustion, and falls. That first summer some 40,000 people hoofed it over Chilkoot Pass and then 28 miles to Lake Bennett. Dead Horse Trail took 45 miles getting to the lake, from which the Yukon ran to the sea, its flow punctuated by rapids.

The border between the Alaska Territory and the Yukon Territory of Canada was fluid, especially along the panhandle. Americans claimed Alaska extended to Lake Bennett. British authorities said Skagway, Dyea, and Haines belonged to Canada. Upon routing the French in 1763, Britain had ruled Canada as a cluster of individual colonies until 1867, when the empire encouraged Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia to form the Dominion of Canada. The dominion enjoyed limited domestic authority and had no power in foreign affairs. British Columbia joined the dominion as a province in 1871. Arriving at Dyea from Vancouver in August 1897, Inspector Charles Constantine and 20 men of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police began to enforce Canadian rule along the routes to the Yukon. Constantine had men occupy Skagway, Dyea, and Haines. At Skagway, mounted police commissioner Zachary Taylor Wood, a Canadian citizen and great-grandson and namesake of an American president, had Mounties build a post and fly the Union Jack. By October the Mounties believed they had secured Canada’s claims to the area.

The hordes tramping to the Yukon included Captain Patrick Ray and Lieutenant Wilds Richardson of the U.S. Army. Sent by the War Department, the officers, in mufti, were operating separately and clandestinely to learn how much gold was at stake and to gauge British military strength in the area. The two returned to Seattle in September with recommendations for U.S. Army fort locations and a warning, based on hearsay, of incipient starvation conditions in the Klondike. According to Ray, only rationing by storekeepers there was keeping people alive.

He was wrong.

Canada was not prepared for that December’s American bombshell. In office since March, President William McKinley faced a gold shortage even though in the Yukon his countrymen were mining gold by the ton. After keeping mum about the Army’s movements up north, McKinley told Congress on December 6, 1897, that he was ordering the U.S. Army to occupy the Klondike to prevent the starvation alleged in Ray’s sketchy report. The president called the expedition a humanitarian mission.

Just after Christmas, U.S. Army Colonel Thomas Anderson landed at Skagway with an advance guard of the 14th Infantry from Vancouver, Washington, to occupy the town. Anderson, confronting six Mounties at their Skagway post, ordered the Union Jack lowered, claiming the bastion was on American soil. The Canadians balked until American soldiers surrounded them. Anderson ordered the Mounties across White Pass to Lake Bennett, claimed by the United States as the border. Mounties could come to Skagway for supplies as long as they were not in uniform. Rather than retreat to Lake Bennett, the Mounties, under orders from headquarters, built a post atop White Pass and another atop Chilkoot Pass.

Fearing an American coup, the dominion government in Ottawa sent Northwest Mounted Police Commissioner Samuel Steele with 196 Mounties in January 1898. Reinforcing the Mountie posts at the passes, Steele sent patrols to identify any “back door” route the American army might take into the Yukon. A force of 18 Mounties went to Pleasant Camp, outside Haines, led by Inspector Arthur Jarvis. To prevent another starving winter in Dawson, Inspector James Walsh required that prospectors traveling through Chilkoot and White passes have 2,000 lbs. of food to get past the checkpoint. The disaster theme, which McKinley already had promoted, captivated the American press. Newspapers ignored the implied threat of American troops seizing Canadian gold fields, instead featuring the need to stop the starvation in Dawson and highlighting orders to the Yukon Field Relief Force to guarantee Canadian sovereignty in the Klondike. Since Canada lacked the military muscle to stop Americans from shipping gold out of the territory, no American feathers were ruffled.

Lake Bennett’s shore was now a tent city of 30,000, its inhabitants waiting to ride the thaw downstream to the Klondike. Early spring arrivals reported that in April 1898 the United States had declared war on Spain. In Canada, the headlines were about tensions between the British Empire and the Transvaal Republic of South Africa over gold and the possibility of Canada having to send troops to fight the Boers.

On May 8, 1898, Canada mustered at Ottawa a Yukon Field Force of 203 men, a quarter of the dominion’s tiny army. The force traveled to the Pacific Ocean by rail, then sailed north along the Pacific Coast and up the Stikine River near Wrangell, Alaska. At Glenora, British Columbia, Field Force men, in scarlet jackets and white pith helmets, disembarked for the march to the Yukon. Guided by Hudson Bay Company scouts—the company also provided 300 mules for the expedition—the dominion troops hacked through mosquito-infested forests, hauling two Maxim machine guns to reinforce the Mountie positions at Chilkoot and White passes.

Reluctant to send troops through the Coast Range to confront the Mounties at the passes, the U.S. War Department shipped men to Valdez with orders to follow the 1884 All-American Route. That bogus path’s author, William Abercrombie, was in command. He and his troops encountered frustrated prospectors who had tried to follow Abercrombie’s fake map. Abercrombie assigned Captain Patrick Ray, the gold rush spy, to go up the Yukon to establish forts should the United States undertake a military incursion into the region. Abercrombie and company spent months hunting a route from Valdez to the Klondike.

On May 29, 1898, the Lake Bennett ice broke up; within 48 hours, more than 7,000 boats and rafts carrying would-be millionaires had put in to ride the Yukon and its rapids to riches. At each stretch of white water, Mounties maintained watch to recover the dead.

The gold rush continued through 1898, gradually displaced from the front pages by the Spanish-American War in Cuba and the Philippines and the standoff between the British and the Boers. These conflicts eased American and Canadian inclinations toward military build-ups along the Yukon. Tensions lessened further when gold strikes at Coldfoot, Hope, and Fairbanks in Alaska redirected prospectors from the Yukon. Commissioner Steele ordered half the Yukon Field Force back to Vancouver, British Columbia.

In 1898-99, as ordered, U.S. Army Captain Ray established forts along the Yukon at Egbert, Gibbon, Circle City, and Rampart, Alaska. In October 1899, Britain declared war on the Transvaal Republic. Scores of Yukon Field Force men eventually fought there. The Canadian/American border remained a concern, as did construction of American military installations in disputed territory, such as Fort William Seward at Haines. That town was claimed by Canada, which was agitating for a border with Alaska that gave the dominion a port to the Yukon at Dyea, Haines, or Skagway. William McKinley, pursuing re-election in 1900 with well-regarded New Yorker Theodore Roosevelt as his running mate, again won the presidency, only to be assassinated in September 1901. Among his emphases as successor, Roosevelt stressed settling the Alaskan border. A commission of three Americans, two Canadians, and a representative of the United Kingdom convened. In 1903, perhaps trying to propitiate the Americans as allies against Germany, the British commissioner aligned with the Americans to establish the border along the Coast Range line formed by the Mountie positions at Chilkoot and White passes. The United States gave up claims to the area around Lake Bennett for a clear title to Haines. The Canadians, deprived of a port at Haines, Skagway, or Dyea, felt betrayed by the mother country. “So long as Canada remains a dependency of the British Crown the present powers that we have are not sufficient for the maintenance of our rights,” Canadian Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier told Parliament.

The Klondike Gold Rush generated impressive results. According to Canadian historian Pierre Berton, a claim held by prospector Swiftwater Bill Gates was literally knee-deep in gold. In two hours, Jim Tweed took $4,284 worth of gold; Frank Dinsmore, in a day, tallied $24,489. Albert Lancaster averaged $2,000 a day for eight weeks. Clarence Berry left the Klondike with $1.5 million in gold, before departing setting by his cabin in the Yukon a coffee can filled with nuggets and a bottle of whiskey beside a sign reading, “Help Yourself.” Of 100,000 who tried for the Klondike, 4,000 found gold—500 of those enough gold to qualify as millionaires.

Some date the Klondike rush’s end to an April 29, 1899, fire in a Dawson dancehall girl’s room that spread until it destroyed the town. On the heels of the Dawson blaze came word that at Nome the beach was full of gold dust; nearly overnight, 8,000 people left. Mining, mostly corporate, continues in the Klondike, which between 1896 and 2013 yielded some 14 million ounces, or 437.5 tons, of gold.

George Carmack, he of the original strike on Rabbit Creek, long since renamed Bonanza Creek, left Kate. Stake in hand, he headed south to Seattle. He remarried. His second wife, Marguerite, put his fortune into real estate. Carmack never got over gold fever, and spent the rest of his years roaming goldfields in the Lower 48, hoping for another mother lode. He was 62 when he died in 1922, working a new claim.