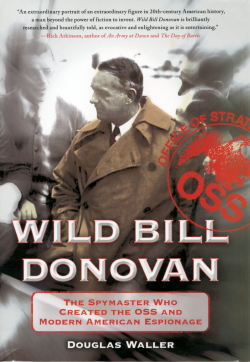

Wild Bill Donovan

Wild Bill Donovan

The Spymaster Who Created the OSS and Modern American Espionage

By Douglas Waller. 480 pp.

Free Press, 2011. $30.

‘Bill Donovan is the sort of guy who thought nothing of parachuting into France, blowing up a bridge…then dancing on the roof of the St. Regis Hotel with a German spy.” Such was movie director John Ford’s assessment of his wartime boss, William “Wild Bill” Donovan—America’s greatest-ever spy chief.

Donovan’s life was ready-made for the movies. In the First World War, as a colonel, he fought with exceptional bravery, receiving the Medal of Honor and three Purple Hearts. By the time President Roosevelt was elected in 1932, the irrepressible Donovan had made a fortune on Wall Street and a name for himself as a brilliant and aggressive lawyer. Although Donovan was a Republican opposed to the New Deal, he shared Roosevelt’s growing fears about the rise of militarism and fascism in Europe. As war engulfed Europe and beyond, Donovan became what Roosevelt described as “my legs”—his most trusted emissary abroad.

In 1942, Roosevelt tapped Donovan to head the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a new organization set up to aid resistance in Europe and carry out espionage. So forceful was Donovan’s brute determination that, in a matter of months, he managed to create an intelligence service from scratch, or “minus zero” as he later stressed. By 1944, he commanded a secret army of over 10,000 agents, analysts, and other operatives who had infiltrated every theater of combat. They pulled off many daring missions and their immense bravery was never in doubt. But how necessary were they? And what impact did they have? Today, many historians agree that the OSS and its British sister, the SOE, were glamorous yet minor sideshows that had negligible effect on the war’s outcome, unlike the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, for example.

As the war drew to a close, Donovan’s organization even began spying on the Russians, long before the Cold War began to heat up. But this growing power also brought the OSS chief into conflict with the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover, who effectively smeared Donovan as a reckless womanizer and persuaded Truman to dismantle his rival empire. The decision came as a heavy blow to Donovan, who had wanted to continue on as America’s premier spymaster. It was doubly galling to see the organization he had created quickly spring back to life in 1947, in the form of the CIA, but without him at the helm.

Donovan’s postwar government roles were far less glamorous: he was heavily involved in preparations for the Nuremberg war trials and later served as ambassador to Thailand. When he died in 1959 at age 76, President Eisenhower was one of many who mourned his passing, declaring him to be “the Last Hero.”

Douglas Waller’s new biography is highly engaging, sprinkled with fresh revelations, and based on diligent and extensive research. One comes away from this superb portrait wondering what Wild Bill would think of our present intelligence apparatus—a sprawling behemoth far beyond what even he might have dared to create, with internal conflicts and miscommunications he would recognize.