In November 1850, Gottfried Kinkel was locked up for life in Berlin’s Spandau Prison. The university professor had been among leaders of a spate of unsuccessful revolutions to sweep German-speaking regions of Europe in 1848-49. A student and revolutionary follower of Kinkel’s, Carl Schurz, vowed to spring his mentor. Schurz, 21, also had been incarcerated for his politics, but he had escaped confinement and fled to Zurich, Switzerland, from which he secretly returned to Berlin with a jailbreak scheme in mind. Through like-minded friends, Schurz met and cultivated disaffected Spandau jailer George Brune, who for a price agreed to spring Kinkel.

The prisoner was in a third-floor cell. One evening, as fellow guards were celebrating a birthday at a nearby inn, Brune, seeing an “all-clear” signal flashed by lantern, looped a rope around Kinkel’s waist and lowered him out his cell window to Schurz, waiting below. As Kinkel had feared, he loosened bits of the old prison’s masonry walls during his descent—but to their good fortune, the clatter was obscured by a passing horse cart with iron-rimmed wheels. Kinkel and Schurz quickly boarded a waiting carriage, traveling 150 miles north to the North Sea port of Warnemunde. Posing as merchants and using aliases, they sailed to Edinburgh, Scotland, and then headed to London. In 1852, Schurz left Britain for America, where he became the most prominent of an influx of energetic and influential European emigres, who have come to be known as “48ers.”

Understanding the 48er phenomenon demands familiarity with Europe’s revolutions of this period. After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the continent came under the “Metternich System” of autocracy. Royal families ruled every state in the region; even once-revolutionary France had reinstalled its monarchy. But beneath a veneer of order maintained by repression, republican dissatisfaction roiled, especially among the educated. Starting in Sicily in January 1848, uprisings spread to France and soon engulfed the entire continent, reaching as far as Ireland.

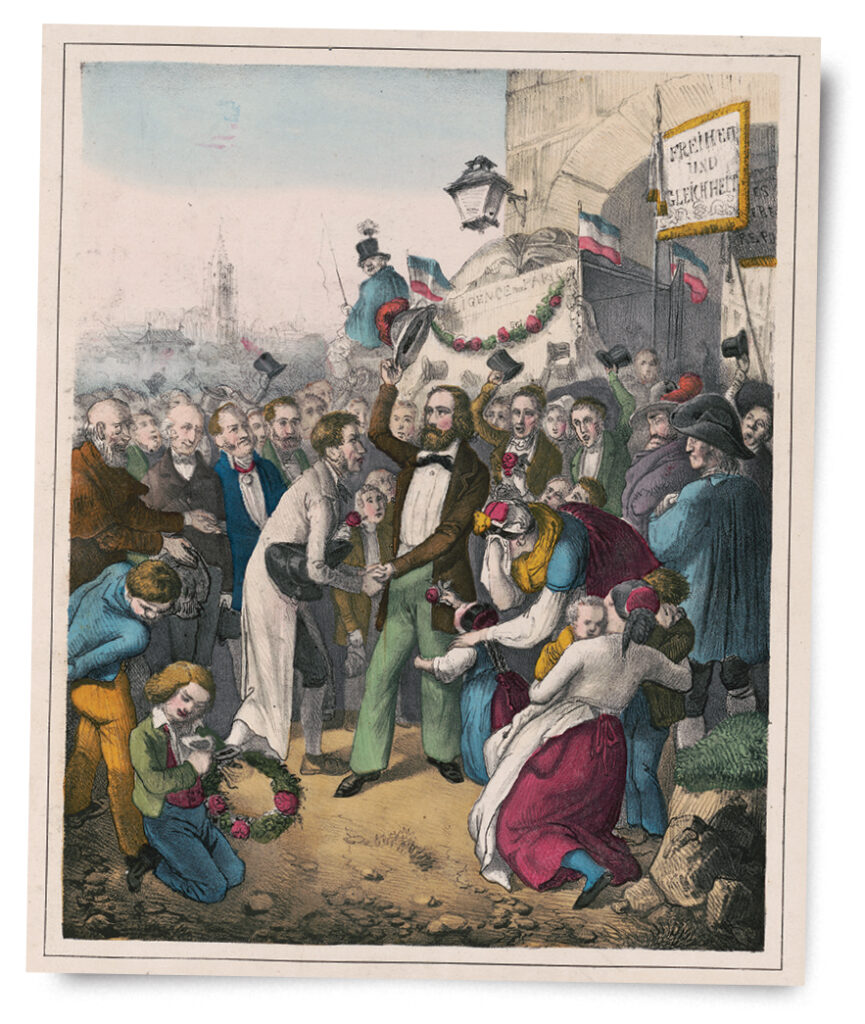

The German Confederation comprised 39 states sharing Teutonic cultural identity and the German language. Liberals around the Confederation, intent on corralling those 39 principalities into a unified republic, formed the Frankfurt National Assembly—an impressive sounding but powerless entity. Hardliners urged armed revolt; German radicalism had its base in the southwestern state of Baden, which saw several uprisings. In April 1848, radical lawyer Friedrich Hecker proclaimed a republic, then led a march through Baden, hoping to spawn a mass movement. He miscalculated and had to flee to Switzerland. Tavern-goers hailed him in the Heckerlied or “Hecker Song”:

When the people ask, is

Hecker still alive?

Can you tell them?

Yes, he’s still alive.

He’s not hanging from a tree

He’s not hanging on a rope

He has his dream of

A free republic

As had happened in Baden, revolutions across the German principalities foundered after they confronted the strength of the rulers’ armies. Revolutionary leaders were imprisoned, executed, or were wanted men with a price on their heads, although the movement’s foot soldiers were granted amnesty, according to The German-American Forty-Eighters, edited by Don Heinrich Tolzmann. Some took refuge in Switzerland, England, or France, but 4,000 to 10,000 ended up in the United States.

German speakers were not the only 48ers; some hailed from Hungary and Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic, and other European locales. But most did come from the Fatherland. “The typical Forty Eighter,” writes Dann Woellert in The Cincinnati Turner Societies, “was a male in his twenties, unmarried, in excellent physical condition, politically enlightened, and financially stable or coming from a family of means.” The average 48er was anti-clerical, which understandably could set off conflict with devoutly religious German Americans.

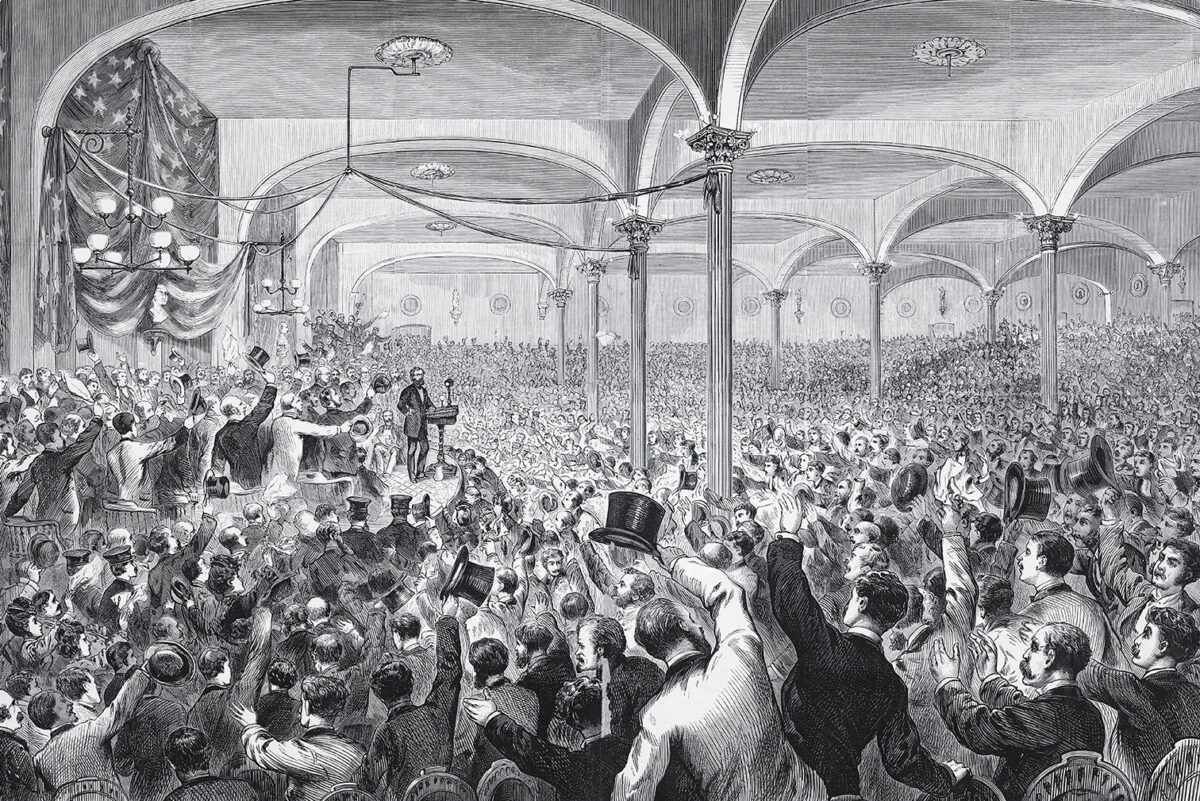

When Friedrich Hecker arrived in New York in October 1848, thousands of freedom-loving German Americans lined the wharf to welcome him. In Boston, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and other large cities, he was likewise celebrated. Non-celebrity 48ers had it rougher. An 1887 reminiscence by M.J. Becker, included in Tolzmann’s anthology, recalls that Becker, who in the old country had studied mathematics and engineering, found himself on Long Island tending radishes and onions. Becker’s friend, an accomplished sculptor, was getting by carving cigar-store Indians. Those who mastered English were able to resume Old World professions such as law, medicine, pharmacy, and teaching. Some flocked to journalism that did not require learning a new tongue: wherever German immigrants clustered, German-language newspapers proliferated. Others went into business or agriculture. Carl Schurz tried farming in Watertown, Wis., before passing the bar in 1858. Hecker had a successful farm in Summerfield, Ill., where he often received fellow refugees.

Some 48ers favored New York, Philadelphia, and other established Eastern immigrant centers. Midwestern cities with existing German populations also drew newcomers; the most prominent were Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Milwaukee. A heavily Germanic Cincinnati neighborhood across the now-defunct Miami & Erie Canal from downtown, became known as Over the Rhine for its location, growing into a “veritable Deutschland” rich in taverns, breweries, music halls, German bakeries, and cigar-makers.

German and Czech 48ers settled in smaller numbers in the Hill Country of central Texas, to which Germans had been coming since the 1830s. Luckenbach, Texas, was named for German nobleman Jacob Luckenbach, one of the first settlers. Tejanos—descendants of the original Mexican settlers of Texas—also populated the region where, thanks to German and Czech influence, the polka and the accordion worked their way into Tejano music.

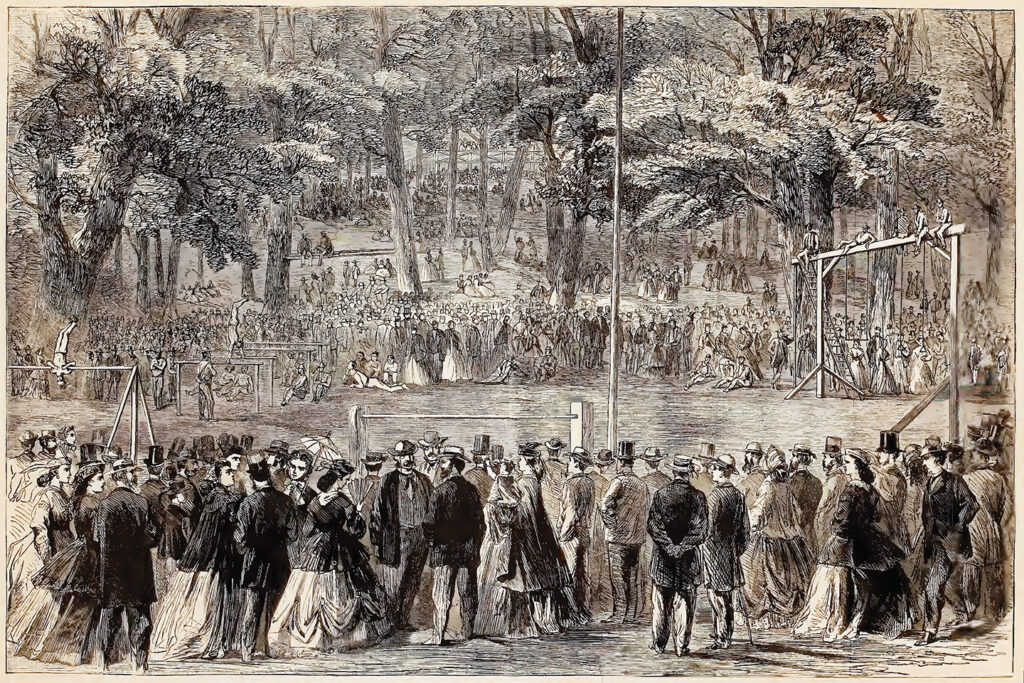

The 48ers had a hand in popularizing physical fitness in the United States. In Germany, many had been members of the Turnverein, or Turner movement, a discipline that stressed gymnastics, exercise, and “a sound mind in a sound body.” When Hecker visited Cincinnati in late October 1848, several recent immigrants asked him about establishing a Turnverein there. Hecker enthusiastically approved, calling the movement “the carrier, developer and apostle of the free spirit.” Soon, Turner societies were spreading nationwide.

Fresh from the whip of monarchic rule, 48ers fervently opposed slavery. “The Louisville Platform,” an 1854 manifesto by 48ers in that Kentucky city, called slavery “a political and moral cancer” and demanded repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law. But 48ers’ anti-clerical bent put them at odds with the Abolitionist movement, whose mainstays often were preachers. Many abolitionists also advocated strict temperance, anathema to lager-loving Germans. They found political haven in the new Republican Party, formed in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which opened the Kansas and Nebraska territories to slavery. Officially, Republicans opposed the extension of slavery into the Western territories, but many, if not most, had a “hidden agenda”: ending slavery altogether. When the party ran John C. Fremont for president in 1856, Illinois Republicans chose two electors-at-large—Hecker and Abraham Lincoln. In 1860, Hecker and Schurz campaigned for Lincoln, Hecker mainly speaking in German and the younger Schurz orating in both German and English.

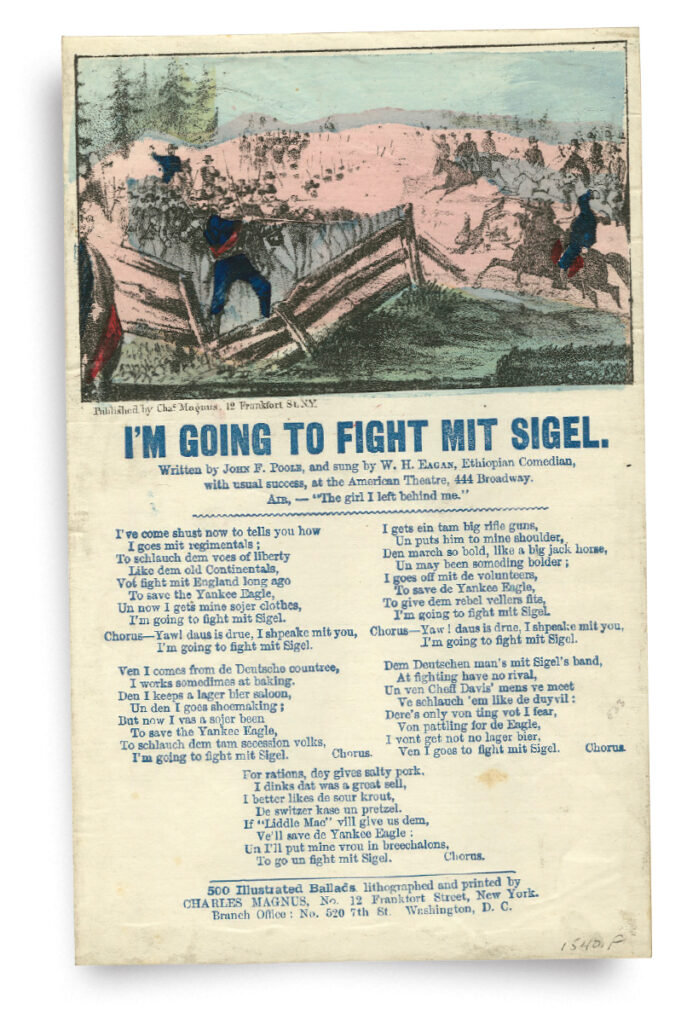

The Civil War was the 48ers’ finest hour. More than 200,000 German-born immigrants enlisted in the Union Army, first among them many 48ers seasoned at combat by the 1848 revolutions. Entire Turner societies joined en masse. The highest-ranking German American officer during the Civil War was Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, a 48er from Baden. A commander in the revolution of 1849 there, he came to the United States from England in 1852, became a teacher, and rose to be superintendent of St. Louis schools. After Sigel accepted the politically motivated offer of colonelcy in the Army, Germans throughout the Midwest volunteered to fight “mit Sigel.” Irish American tunesmith John F. Poole, known for writing the song “No Irish Need Apply,” turned the phrase into a comic dialect number sung to the tune of “The Girl I Left Behind Me”:

I’ve come shust now, to tells you how

I goes mit regimentals

To schlag dem voes of liberty

Like dem old Continentals

Vot fights mit England long ago

To Save de Yankee eagle

Und now I get my sojer clothes

And goes to fight mit Sigel

CHORUS: Ja, das ist true, I speaks mit you

I goes to fight mit Sigel!

Sigel had his best moment of the war in March 1862 at Pea Ridge, Ark., where his men surprised a Confederate force, pounding the foe with artillery until they retreated. At Wilson’s Creek, Mo., in 1861, however, he had left a flank exposed, leading to a devastating Confederate counterattack. Sigel stumbled at Cedar Mountain, Va., in 1862 when he delayed because he was waiting for a supply train to deliver meals for his troops; and in 1864 at New Market, Va., when less than half his troops were on the battlefield as fighting began. Sigel was contentious, often bickering with fellow officers. Henry Halleck, the Union commander in chief in 1862–64, harped about Sigel in a letter to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, griping about the “damned Dutch” (a corruption of Deutsch, meaning “German” in German) who “constitute a very dangerous element in society as well as the Army.” After fighting at Harpers Ferry in July 1864, Sigel was relieved of his command.

Like Sigel, Schurz was a “political general,” appointed by Lincoln to curry favor with German Americans. Schurz’s division in the Army of the Potomac’s 11th Corps included several German regiments. Though better regarded than Sigel by fellow officers, Schurz too came in for criticism. The press reviled Schurz and the German troops as “flying Dutchmen” for retreating when overwhelmed by Confederate forces at Chancellorsville. Schurz demanded a hearing by a military court, but got none. At Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, Schurz’s troops fought well, but had the bad luck of deploying on terrain that was hard to defend, as well as being outnumbered. His regiments withdrew to Cemetery Hill, where he regrouped and the next day helped drive back the Confederates.

Hecker also received a commission as a colonel, and in 1862 was given command of the 82nd Illinois Volunteers, mainly German in composition but leavened by Scandinavians and a Jewish company organized in Chicago. Hecker, who was wounded at Chancellorsville while fighting under Schurz, also saw action at Missionary Ridge and elsewhere. The invective aimed at Sigel and Schurz did not splatter him; an inquiry into a disappointing showing by troops that he and other officers led at the Battle of Wauhatchie, Tenn., in 1863 found, “So far as the conduct of Colonel Hecker is concerned, it is not deserving of censure.”

When the fighting ebbed, 48ers in blue relaxed together, enjoying Gemutlichkeit, or “good feelings.” Sigel once invited General James Garfield to his headquarters for tea; Sigel and Schurz entertained Garfield with their piano playing. Toward the end of the war, at Lookout Mountain, Tenn., Schurz and Hecker amused themselves with the German card game Skat.

Military or civilian, German Americans in the North saw supporting the Union as a way to gain acceptance as Americans. Few Germans had emigrated to the South, where opposition to the Confederacy was a black mark. In Texas, German-majority counties voted against secession in 1861. When Texas joined the Confederacy, Germans there formed a militia—the Union Loyal League—and resisted the draft. In April 1862, Confederate troops came to the Hill Country to enforce conscription, burning homes and making mass arrests. That August, 60-odd Germans took off for Mexico, planning to reach Union-held New Orleans from there. Confederate pursuers caught them at Nueces, killing 19 and wounding others. Texas Germans rejoiced when the Union won the war.

After the war, Schurz continued in public life. In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent him South to examine “the Negro problem.” Schurz found that powerful Southern Whites still believed that coercion was the only way to get African Americans to work, that African Americans were being deprived of their rights, and that they were constantly in danger. Johnson, a Unionist who championed the poor Whites over freed Blacks, ignored Schurz’s report.

In 1868 Schurz was elected as a Republican U.S. Senator from Missouri. He soon did a seeming about-face: In 1870, he helped found the “Liberal Republican” faction whose adherents believed equality for African Americans in the South had been achieved, and that the priority now was to restore self-government in the former Confederate states. In 1871, he voted against the Ku Klux Klan Act, which permitted federal action against that terror organization, on the grounds that the measure gave too much power to the president. The Liberal Republicans disappeared after their presidential candidate, Horace Greeley, also endorsed by the Democrats, decisively lost to incumbent Ulysses S. Grant. In the Senate, Schurz was noted for his advocacy of civil service reform, a major issue in that era of the spoils system.

Schurz lost his Senate seat in 1874. In 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him secretary of the Interior. In 1879, Schurz took a well-publicized trip to the West, meeting with Native American chiefs. In Washington, Schurz met with Chief Standing Bear of the Ponca tribe, which had been forced to leave Nebraska and resettle in Oklahoma. Schurz expressed sympathy with the tribe’s hardships. But when Standing Bear and his people tried to return home without permission, Schurz ordered the Army to arrest them and turn them back, drawing sharp criticism. Upon leaving Interior in 1881, Schurz moved to New York and turned his efforts toward journalism. Omaha Daily Herald Assistant Editor Thomas Tibbles publicized the case of the Poncas, and aided by lawyers working pro bono, Standing Bear sued for his release and won. The Hayes administration shortly permitted some to return to their homeland in Nebraska.

Other 48ers also went into public service. Some, like Lorenz Brentano and Julius Stahel, were appointed as diplomatic envoys. Others, like Thomas Meagher and Wlodzimierz Kryzyzankoski, were named to high posts in the Western territories and in the Reconstruction-era South. Sigel briefly edited the German-language Baltimore Wecker, then moved to New York and ran unsuccessfully for secretary of state. In the 1870s and 1880s he held local offices, including city registrar, pension agent for the New York District, and district inspector for the common (public) schools of New York. Despite his sketchy military reputation, Sigel remained a hero to German Americans. For years, in certain Midwestern taverns, veterans who had “fought mit Sigel” could get a free lager.

Hecker returned to his farm, occasionally hitting the lecture circuit. In 1871 he applauded the achievement of one of his dreams—a united Germany. But on a visit to the old country in 1873, he was dismayed at the lack of a national bill of rights, the Kaiser’s elevated role, the huge military budget, and rampant anti-Semitism.

In the 1890s, the 48er generation began to die off, but traces remain. A statue of Sigel stands in Manhattan’s Riverside Park, about a mile from Grant’s Tomb. Manhattan also has a Carl Schurz monument and a Carl Schurz Park. Monuments to Hecker stand in St. Louis and Cincinnati. And in Comfort, Texas, the Treŭe der Union (Loyalty to the Union) monument honors those killed in the Nueces Massacre.

Raanan Geberer writes from New York City. He occasionally leads historical hikes and walking tours and plays in several amateur rock bands.

A Baker’s Dozen of 48ers

Mathilde Franziska Anneke, feminist pioneer. During a Baden uprising in 1849, she assisted her husband, Friedrich by delivering messages. They fled to Milwaukee, and Mathilde published the first female-owned feminist publication in the U.S. She lived in Switzerland during the Civil War and wrote anti-slavery fiction; afterward, she returned to the U.S. and devoted herself to women’s suffrage.

Hans Balatka, a Czech conductor and composer, promoted European classical music. As a student in Vienna, he joined a revolutionary group. In America, he settled in Milwaukee and conducted at music festivals there and in Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago, and elsewhere. Moving to Chicago, he led the Liederkranz Society, the Mozart Club, the Chicago Musical Society and other groups.

Lorenz Brentano served as president of the Baden provisional revolutionary government in 1849. He lived in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and finally Chicago, where he became a lawyer. While in Pennsylvania, he founded a German-language anti-slavery publication. He was elected as a Republican to the Illinois legislature during the Civil War. He was U.S. consul in Dresden 1872-76, then served one term in Congress.

Edward Degener, Texas Unionist. Degener, a member of the Frankfurt National Assembly, came to the U.S in 1850 and farmed in the Hill Country. During the Civil War, he was convicted of sedition by a Confederate court. After the war, he was a delegate to two Texas constitutional conventions, served as a Republican congressman in 1871-72 and on the San Antonio City Council from 1872-78.

Dr. Abraham Jacobi, pioneering pediatrician. Jacobi, as a young doctor, was one of several members of the Communist League who were tried in Cologne for revolutionary activities, and he later stayed with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in London. Arriving in the U.S in 1853, he taught at New York Medical College, where he was its first chair of children’s diseases, New York University, and Columbia University. At Mount Sinai Hospital, he established the first Department of Pediatrics at a general hospital. He was a close friend of Schurz; each had a cottage on Lake George at Bolton Landing, N.Y. Jacobi served as president of the American Medical Association 1912-13.

Wlodzimierz Kryzyzankoski took part in the 1848 Polish uprising against Prussia, then fled to the U.S. As a civil engineer and surveyor in the 1850s, he helped railroads push west. During the Civil War, he raised a Polish regiment, was appointed as a general, and fought at Gettysburg and in other important battles. He served as governor of Georgia during Reconstruction.

John Michael Maisch, pharmaceutical pioneer. He came to the U.S. in 1849 and worked in drugstores while studying pharmacy. By 1861, he was teaching at the New York College of Pharmacy. During the Civil War, he was chief chemist at the U.S. Army Laboratory in Philadelphia. He became the editor of the American Journal of Pharmacy and secretary of the American Pharmaceutical Association. In 1869, he drafted a model state law regulating pharmacies.

Thomas Meagher was a leader of the failed “Young Irelander” rebellion in 1848. Exiled by the British to Tasmania, he escaped to New York and founded an Irish weekly. When the Civil War came, he organized the Union Army’s Irish Brigade, was commissioned as a brigadier general, and led the brigade through several battles. Later, he served as territorial governor of Montana.

Bertha Ochs was the mother of New York Times publisher Adolph Ochs. Bertha Ochs came as a teen during the uprising in Bavaria and lived with an uncle in Natchez, Miss. She was a staunch supporter of the Confederacy, and her son Adolph, who became publisher of the Chattanooga Times and later The New York Times, donated to Confederate commemorations. According to author David J. Jackowe, flaglike tile mosaics resembling the Confederate banner that once adorned the Times Square subway station were a nod by designer Squire Vickers in 1917 to the Ochs family’s fondness for the Confederacy.

Oswald Ottendorfer took part in uprisings in Vienna, Saxony, and Baden. Arriving in New York, he started in the Staats Zeitung newspaper’s counting room and worked his way up, eventually serving as publisher 1859-1900. While he leaned Democratic, he supported Lincoln’s war effort. He served one term as an alderman, ran for mayor in 1874 on an anti-Tammany platform, and was known for philanthropy.

Edward Salomon, first Jewish governor of Wisconsin. A revolutionary student at the University of Berlin, he fled to the U.S. in 1849. After working as a teacher and court clerk, he passed the bar in 1856 and practiced law in Milwaukee. He was elected lieutenant governor as a Republican in 1860 and became governor following Governor Lawrence Harvey’s death in 1862. He later moved to New York, where he represented German interests as an attorney.

Margarethe Schurz was Carl Schurz’s wife. She was active in the kindergarten movement, a German creation, and in 1856 opened the first American kindergarten—a German-speaking school, like most kindergartens of the day, in Watertown, Wisconsin. She died at 43 after giving birth.

Julius Stahel, Hungarian 48er and Civil War general. He took part in Lajos Kossuth’s 1848 uprising, fled to England, and in 1859 came to the U.S. Stahel, a German speaker, helped raise a German-speaking regiment. He saw action at both Bull Run battles, Cross Keys, and elsewhere, and received the Medal of Honor. After the war, he served as U.S. consul in Japan and China. He also worked as an engineer and insurance executive. —R.G.

This story appeared in the 2023 Summer issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.