Nestled amid the Blue Ridge Mountains at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers, Harpers Ferry is the northern gateway to Virginia’s fecund Shenandoah Valley. Originally settled in 1733 as a ferry landing on the Potomac, the site on which the present-day town sits was bought by its namesake, Robert Harper, in 1751. Harper continued the lucrative ferry as settlers increasingly moved south into the valley. George Washington had business interests in the area, and family lived nearby, including younger brother Charles, the namesake founder of Charles Town. In 1794 Washington proposed Harpers Ferry as the site of the new U.S. Arsenal and Armory, which opened in 1801. The armory turned out more than a half million firearms before being destroyed at the 1861 outset of the Civil War. The village industrialized further in the 1830s with the arrival of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad.

Harpers Ferry exploded on the national scene in 1859 when radical abolitionist John Brown raided the arsenal. Believing an armed slave insurrection in Virginia would ultimately result in the demise of the “peculiar institution” throughout the South, Brown and 21 followers armed themselves with rifles and revolvers and seized the armory on Oct. 16, 1859. Ironically, a free black railroad worker named Shepherd Heyward was the first casualty. Confronted by armed citizens bolstered by militia from nearby Charles Town, Martinsburg and Shepherdstown, as well as Frederick, Md., Brown and his followers were trapped in a small fire engine house. Two days later Col. Robert E. Lee, commanding a detachment of U.S. Marines from Washington, D.C., ended the fighting. Seven prisoners, including Brown, were soon tried and executed.

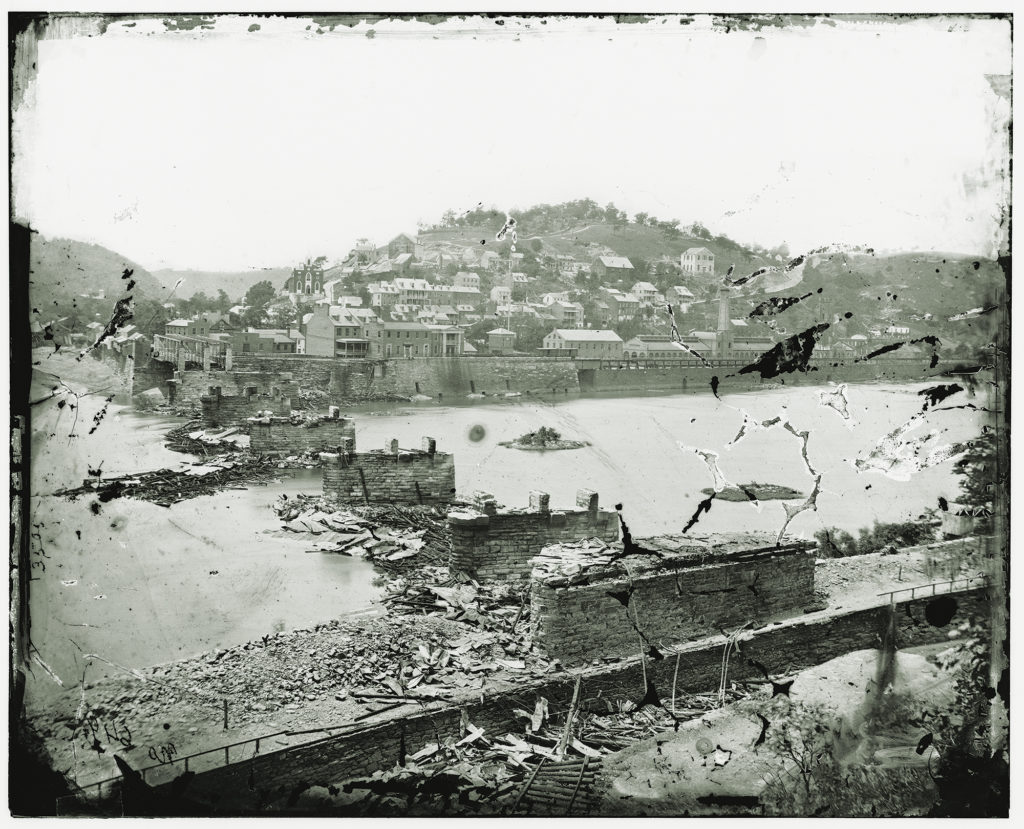

In the raid’s aftermath war clouds billowed as states addressed the matter of secession following Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 election to the presidency. Residents of Harpers Ferry and neighboring towns expressed loyalty to the Union during Virginia’s secession debate. When the state did secede, an armory supervisor with Rebel sympathies sought to turn it over to the Confederacy, but a Union officer had his men torch the buildings before fleeing to Pennsylvania. Within days Col. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson arrived with the Virginia militia to occupy the town. His men salvaged what they could from the armory ruins, including thousands of rifle stocks and much of the machinery. Ringed in as it is by mountains, however, Harpers Ferry was considered indefensible by Jackson’s successor, Confederate Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who withdrew south to Winchester, Va., in June 1861.

A month later Union troops under Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson occupied Harpers Ferry. The town changed hands five more times before Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks made it his headquarters in late February 1862. That May, during his famed Shenandoah Valley campaign, Jackson attacked Harpers Ferry, but Union Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton successfully repelled him. Three months later Lee launched his first invasion of the North and needed a secure supply line from the Shenandoah. Taking a risk, he split his forces. Returning to Harpers Ferry, Jackson defeated 14,000 Union troops under Col. Dixon Miles and captured the town on September 15. He then joined Lee in Maryland for the September 17 Battle of Antietam—the bloodiest single-day clash of the war—which ended with Lee’s retreat and Harpers Ferry back in Union hands.

In 1944 the heart of Harpers Ferry, including the engine house known as ‘John Brown’s Fort,’ was established as Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Harpers Ferry remained under federal control until July 1, 1863, when Union troops who’d been defeated during the Second Battle of Winchester withdrew. When they returned eight days later, Harpers Ferry was no longer in Confederate territory, as on June 20 it and 24,000 square miles to the south and west had been subsumed by the newly admitted state of West Virginia. Union troops briefly lost the town again on July 4, 1864, during Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s bold raid on Washington, D.C., but he withdrew within days, and Union soldiers were back for the war’s duration. A month later Harpers Ferry served as the stepping-off point for Union Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s brilliant campaign that permanently claimed the Shenandoah Valley from the Confederates.

In 1944 the heart of Harpers Ferry, including the engine house known as “John Brown’s Fort,” was established as Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. The touristy town also hosts the National Park Service’s media center and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. MH