Did German Americans’ cowardice cost the Union victory at Chancellorsville? Or should that humiliating loss be laid at the feet of their top generals?

“There is no doubt of the fact that our army was at last accounts in the most cheerful and hopeful condition, and Gen. Hooker, it is represented, had issued an address, paying a high compliment to the army for their conduct thus far in this important movement.” The New York Times voiced this optimism on May 3—reporting, two days behind the actual events, on the beginning of the Battle of Chancellorsville, which everybody hoped would be the end of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia and the war.

The next morning Times readers got a very different story. “Another bloody day has been added to the calendar of this rebellion,” wrote L.L. Crounse for the Times. “At 5 o’clock a terrific crash of musketry on our extreme right announced that Jackson had commenced his operations. This had been anticipated, but it was supposed that after his column was cut, the corps of Maj. Gen. [Oliver Otis] Howard, (formerly Gen. [Franz] Sigel’s corps) with its supports, would be sufficient to resist his approach…. But to the disgrace of the Eleventh Corps be it said, that the division of Gen. [Carl] Schurz, which was the first assailed, almost instantly gave way. Threats, entreaties and orders of commanders were of no avail. Thousands of these cowards threw down their guns and soon streamed down the road toward headquarters.”

Such was May 2, 1863, the day things fell apart at the Battle of Chancellorsville, the most embarrassing engagement ever fought by the Army of the Potomac, if you believe The New York Times. Or you can just take the word of Union Private Darwin Cody, a May 2 survivor with an English-speaking unit, the 1st Ohio Artillery. He wrote: “Our support was all germans. They run without firing a gun…I say dam the DUTCH.”

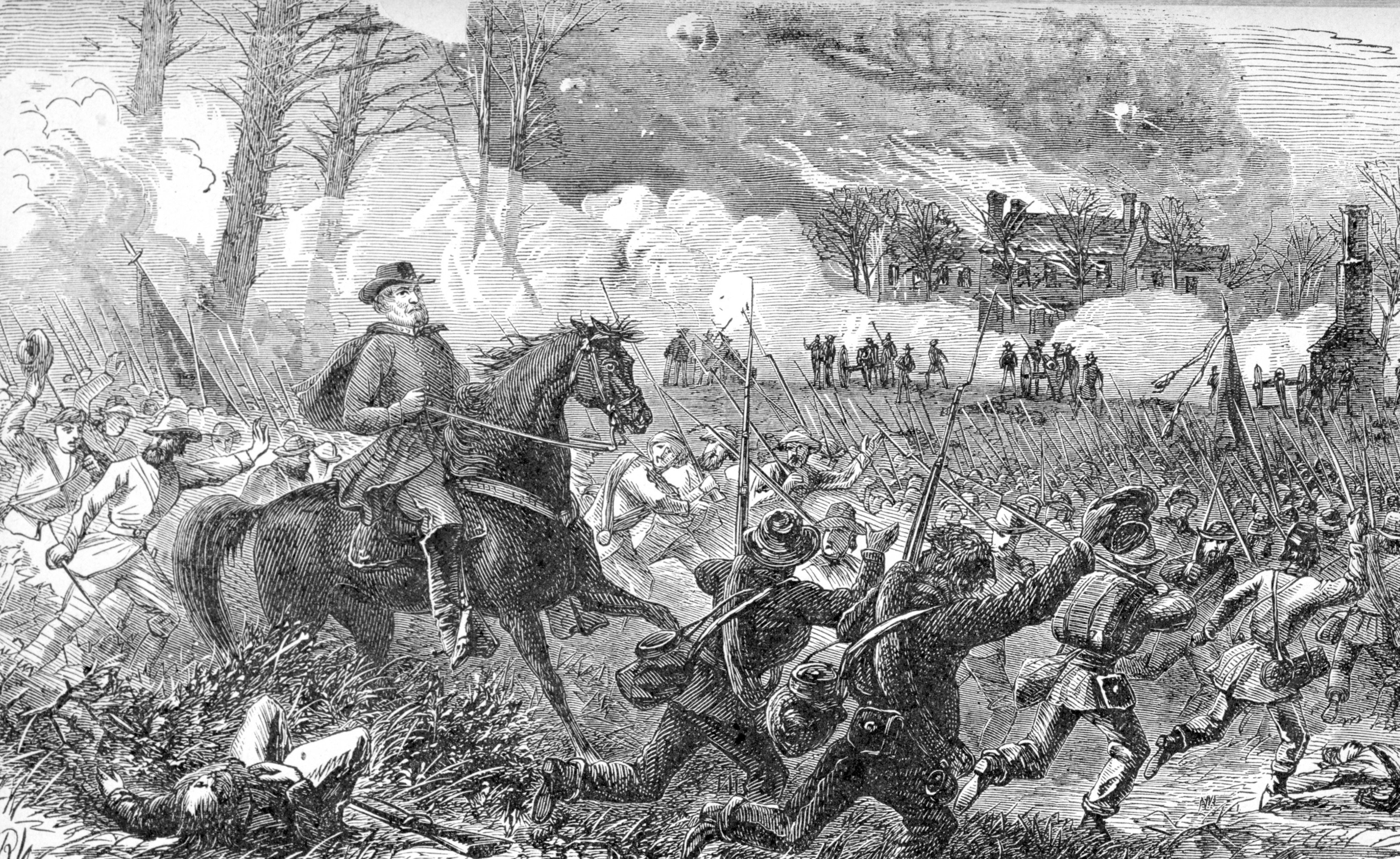

The defeat at Chancellorsville gave birth to the legend of the Flying Dutchmen—the Germans of the XI Corps who supposedly broke and ran at the first sight of Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s 26,000 Confederates bearing down on two understrength Union regiments with 700 soldiers and two cannons. The Flying Dutchmen—merging the name of a mythical ghost ship with a corruption of Deutsche, for “German”— fled all the way down the Orange Turnpike. Tumbling in a chain reaction of compulsive cowardice, they took some of the American-born troops down with them—until nightfall when the accidental shooting of Stonewall Jackson by his own pickets ended the rout on a more hopeful note for the Federals. But was that really what happened on May 2?

The performance of German troops in the American Civil War is one of history’s enigmas. Despite an accomplished heritage, the 180,000 Germans in Abraham Lincoln’s army—the largest contingent of any foreign-born group— are remembered as a liability, even something of a disgrace.

“I think the reason the German regiments so seldom turned out well was that their officers were so often men without character,” Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan wrote in 1887. But McClellan also had praise for a top German officer, Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker, who had fought with McClellan in earlier battles. Blenker’s division—without its commander, who was home dying of injuries suffered in a fall from his horse—was numbered among the Flying Dutchmen of Chancellorsville. A native of Hesse-Darmstadt, Ludwig (later Louis) Blenker fought in the revolutions of 1848 and 1849 on the side of the democratic rebels, then escaped to Switzerland and, after being banished, emigrated to Rockland County, N.Y., where he became a successful farmer and businessman. When the Civil War broke out, Blenker and Hungarian émigré Julius Stahel organized the 8th New York, a two-year regiment, and became its colonel and lieutenant colonel, respectively. “[Blenker] was in many respects an excellent soldier, had his command in excellent drill, was very fond of display,” McClellan wrote. “It would be difficult to find a more soldierly looking set of men than he had under his command.”

Many German commanders of Civil War units—men like Franz Sigel, Carl Schurz, and Hubert Dilger—were also former rebels from 1848. Others had served as officers in the Prussian army that put down the rebellions under the auspices of the German Confederation. This past internal conflict may have been at the core of the almost habitually disappointing conduct of German troops in the Union Army.

Through the 1850s, Prussian-hating radicals were followed to America by a different type of emigrant—members of the Prussian officer caste of minor nobility called Junkers—whose own army didn’t have jobs for them. Career officers who lost out in the promotion shuffle from captain or major to the cherished lifetime position of colonel often made a very shaky transition to civilian life: Detlev von Liliencron, an undoubted nobleman and decorated hero of the Franco-Prussian War, eked out a postmilitary living sweeping out taverns while he wrote some of Germany’s best-loved poetry.

Such a man, minus the poetic talent, was Leopold von Gilsa, a former major in the Prussian Army who had seen service in the brief war against Denmark before he emigrated with his wife from Prussia to the United States in 1850. Gilsa was living in New York City, lecturing and playing the piano in Bowery saloons, when the American Civil War erupted. When patriotic German Americans formed the 41st New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment in June 1861, he was appointed colonel. Of the 33 officers in the 41st New York, 23 had experience in various German armies, and quite a few of the enlisted men were also German military veterans. Many were in their late 20s or early 30s, some pushing 40. They remembered 1848. The command structure was stratified: At the brigade level were former radicals such as Sigel and Schurz, heroes of the radical faction in the revolution of 1848; at the regimental level, Gilsa, the conservative Junker from a proud military tradition but ill-suited to a life of commerce and free enterprise; and in the ranks, tradesmen like most of the 300 victims of the Berlin massacre of March 1848, men who came to America to get away from arbitrary Prussian rule.

The 41st arrived too late to fight at the First Battle of Bull Run but helped cover the Federals’ panicky retreat. The regiment worked on fortifications around Washington, D.C., and Gilsa was served with papers for the first of several courts-martial after reportedly pushing an enlisted man against a tent and insulting him. The matter never came to trial. Over in the 45th New York, things were no better: Lieutenant Joseph Spangenberg, already wounded in the chest in an early engagement, was served with court-martial papers when he called a fellow officer on parade a Schweinhund, a dirty dog, and a Schuf, a gentile hired to clean up after Jews on the Sabbath. Spangenberg’s court-martial never took place either, and he was later promoted to captain, but a collision between these two temperamental Teutonic thunderheads, officers in the same brigade, was only a matter of time.

Colonel von Gilsa was wounded in the leg leading the 41st in the regiment’s first battle at Cross Keys on June 8, 1862. The regiment and the rest of Blenker’s and Stahel’s divisions were repulsed making an attack over an open field against Confederates firing from thick woods; they retired in good order with one man killed, eight wounded and 12 missing. Sigel took over the division. The 41st and 45th again faced the Confederates at the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 28-30, 1862. On Chinn Ridge on August 30, the 41st attacked alone in a vain attempt to recover an abandoned Federal battery but was driven back.

In the battle the 41st lost 103 men; Lieutenant Richard Kurz and 26 enlisted men were killed, 60 were wounded (seven later died), and 12 men were missing or captured. Lieutenant Richard Kurz was among the dead. Gilsa returned after recovering from his wound at Cross Keys and was given command of the entire brigade but without being promoted to the rank of general, which rankled him. The new corps commander, replacing Sigel, was Oliver O. Howard, who had lost an arm at the Battle of Fair Oaks. He was an unknown quantity in the XI Corps, where most of the German regiments of the Army of the Potomac were concentrated. The 41st and 45th New York—the 41st now augmented by soldiers left over when the enlistments of Blenker’s old 8th New York expired on April 22, 1863— became the first two regiments of the 1st Brigade of the 1st Division. This may have been why the regiments found themselves on the extreme right of the Union line at Chancellorsville. Gilsa, an arrogantly outspoken professional, didn’t like the position and said so. His right flank was hanging in the air, just waiting to be turned, and the underbrush made surveillance impossible. He anchored his flank with the only two cannons he had available and sent out pickets a quarter to half a mile.

Shortly, the German pickets reported that Confederates appeared to be moving along their front in considerable numbers. Gilsa sent a courier to General Howard (several other German officers had also reported unexpected activity), but the courier was ignored. Gilsa then rode to Howard’s headquarters and reported Confederate movements across his front. He was rebuffed and all but accused of cowardice.

Hubert Dilger, another Baden revolutionary in the Union Army, was commanding Battery I of the 1st Ohio Artillery, a mixed unit of American-born German Americans in support of the XI Corps infantry. A fearless swashbuckler and a splendid horseman, Dilger was known as “Old Leatherbreeches” because he favored tailormade buckskin riding trousers after wearing out several sets of kersey blue. Dilger got so close to the Confederates moving through the woods that he had to ride like mad and duck under tree limbs to avoid being captured. When he barely made it back alive to Howard’s headquarters, he too was ignored.

What the Prussian professionals and the Baden swashbuckler alike had reported to the Americans, of course, was Stonewall Jackson’s famous flanking march while it was still in progress. Neither General Howard nor Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, the Union commander, would believe that they were being outflanked, despite repeated warnings from Gilsa, Dilger and several other Germans. At about 4:30 p.m., Gilsa sent out a squad from the 45th New York, commanded by Captain Spangenberg. The hot-tempered but fearless Spangenberg bumped into the Confederates and got close enough to see their overwhelming numbers. Shots were exchanged, and Spangenberg, unwilling to pit a half-dozen Germans against the entire Army of Northern Virginia, rushed back and bumped into Gilsa at the hanging flank of the 41st. Gilsa, mistaking prudence for panic, struck Spangenberg with the flat of his sword in rebuke—a dueling offense back in Germany—and ordered the brigade to arms. The 41st, 45th, and 54th New York and the 153rd Pennsylvania stood to face the woods and were ready for battle when 26,000 of the Confederate army’s best soldiers broke cover and advanced on them.

Compounding Howard’s and Hooker’s deafness to the dispatches and warnings they had received was a natural anomaly: an “acoustic shadow.” This atmospheric phenomenon essentially put a lid on sound waves from the battle, preventing the generals from hearing the fighting.

Gilsa’s soldiers stood their ground and fired three volleys into the charging Confederates. They were loading for a fourth—no doubt with shaking fingers—when Gilsa saw he was being outflanked. He called one orderly to order a withdrawal, and the orderly was shot right before his eyes. He called a second orderly, also shot before his eyes. Gilsa himself rode up and down the ranks roaring the orders to pull back. Some of the enlisted men backed away in fighting stance, and others simply broke and ran. The brigade pulled back to the next supporting position, the 75th Ohio, and made a stand that lasted about 10 minutes.

At this point, many of the bravest soldiers had already been shot, and more and more fugitives were headed for the rear. Gilsa rode back, shouting at the men to stand, and bumped into Spangenberg, also calling for a rally. This confrontation flared into an argument that climaxed when Gilsa brought the flat of his sword down on Spangenberg’s head and knocked him out. The 41st and 45th continued to shed fugitives, but the bulk of both regiments remained intact and kept firing while pulling back. The 41st alone lost 61 men— about 20 percent casualties, enough to break any nonelite unit. The regiment had stopped with the rest of the brigade at General Hooker’s headquarters, about two miles from the point of contact where Jackson broke out of the woods. Losses from the 45th (Spangenberg was carried away and later regained consciousness) were on the same level.

Just behind the two flank regiments, the 54th New York also put up a good fight. “The conflict was a fierce one, and several times the flag was almost captured, three color bearers being successively wounded,” historian William F. Fox wrote. “However, the regiment held its own until almost surrounded by the enemy when, to avoid capture, it fell back fighting bravely. The casualties were 1 killed, 23 wounded, and 17 missing, a total of 42.” The 153rd Pennsylvania, a largely American-born, nine-month regiment that had never seen combat before, simply crumbled when it took fire from both sides.

The Ohio Brigade, whose divisional commander was Brig. Gen. Charles Devens Jr., was next in line. These troops were not German immigrants but mostly American-born—the 17th Connecticut had been assimilated somehow into the Ohio Brigade. General Devens heard the noise up the Orange Turnpike—perhaps later than he should have due to the acoustic shadow—but he took no action. Two of his own colonels said later that he appeared to be drunk. When Stonewall’s Confederates pushed the remnants of Gilsa’s Brigade into Devens’ Ohio Brigade, the American-born troops fell into the same pattern:They stood and fought briefly, pulled back 500 yards, stood again, and then broke and made for the rear as their regiments were cut to pieces. Four out of five colonels were killed, wounded, or captured, and the Ohio Brigade lost 688 men. Some of the American-born soldiers stuck by their officers and regrouped at headquarters. Others brought panic to units that had not yet made contact.

Gilsa’s Brigade—the first of the Flying Dutchmen—actually maintained better unit cohesion than the long-time Americans. Gilsa said in his report that most of his men fought well but that many of his officers hadn’t shown the proper spirit of cooperation.

Stonewall’s ax then fell on Carl Schurz’s brigade, the next in line as Gilsa’s men pulled back in good order or, in some cases, ran for it, joined by their American- born counterparts in the Ohio Brigade. The 58th New York, a mixed unit made up mostly of Germans and Poles, had also attempted to warn headquarters about Stonewall’s flanking maneuver and also had been ignored.

Historian Fox later described the action: “Schurz’s regiments held the ground for half an hour or more, and then finding that the enemy overlapped their line on either flank fell back, stopping from time to time to deliver their fire.” The 58th counted 31 casualties out of 239 officers and men engaged. Its commanding officer, Captain Frederick Braun, was shot off his horse and mortally wounded leading his men. Another mixed-heritage regiment with a large number of Germans, the 119th, also lost its commander, Colonel Elias Peissner, when he, too, was shot off his horse. “Notwith – standing the loss of its gallant colonel and one third of its entire rank and file, the regiment retired from the field in good order,” Fox recorded of the 119th New York. Schurz noted that every regiment in his brigade had its colonel killed or wounded by enemy gunfire.

Captain Dilger now brought his six cannons into action, placing them on a rise and firing over the heads of the Union infantry. The Confederates captured one of his guns and two guns of Captain Michael Wiedrich when these two redoubtable Germans waited too long to pull back. Once again, Dilger narrowly escaped capture.

While Gilsa’s Brigade, the Ohio Brigade, and then Schurz’s Brigade were being chewed up and spat out, troops farther down the Orange Turnpike, where the acoustic shadow pervaded, apparently were oblivious to the carnage. When spectators first heard the gunfire, they saw crowds of American-born and Germanborn men fleeing toward the main troop body, some without their muskets. The rout included not only infantry but also “battery wagons, ambulances, horses, men, cannon, caissons, all jumbled and tumbled together in an apparently inextricable mass, and that murderous fire still pouring on them,” wrote Thomas Cook for the New York Herald.

Bolstered by their artillery and the approach of darkness, the Union army finally stopped Stonewall’s advance. The wounding of Jackson later that night enabled Hooker to disengage and head back home after being defeated by an army half the size of his own. The much-maligned XI Corps— later disbanded—had inflicted about 1,000 casualties on Stonewall Jackson’s men and held up the Confederate advance for two hours. The corps lost 217 killed, 1,218 wounded, and 972 captured or missing.

Nonetheless, even before Stonewall Jackson died, his humbled Union adversaries began weaving the Legend of the Flying Dutchmen. In the process, careers were tainted: Gilsa never made general, much to his own disgust, and he resigned when the bulk of his men left the service at the end of their three-year hitch. He died in 1870, at 45, while working as a government clerk, his health damaged by wounds and war service. Dilger received the Medal of Honor for Chancellorsville and later service at Gettysburg, but he remained a captain while less distinguished soldiers were promoted over his head. Spangenberg, whose warning could have staved off the rout, was promoted to major and to colonel on the same day—after the war was over.

The Federals’ disaster at Chancellorsville may have been due in part to the abrasive relationship between Prussian conservatives and South German radicals among the German-born officers in Lincoln’s army. And the rolling shock of Stonewall Jackson’s sudden arrival on the flank of three Union brigades was due in part to the acoustic shadow and the strange failure of Howard, Hooker, and Devens to listen to warnings delivered in ample time. Neither the fighting qualities of the German enlisted men nor the capability of their officers—leaving out some problems in personality clashes—led to the black day of the Army of the Potomac. But the Legend of the Flying Dutchmen as the culprits of Chancellorsville lives on. Everybody needs a scapegoat.

John Koster recently contributed “Survivor Frank Finkel’s Lasting Stand” to the Weider History Group’s Wild West (June 2007). Minjae Kim provided research for this article.

Originally published in the May 2008 issue of America’s Civil War. To subscribe, click here.