For two nights have waited on quayside lying on ground, finally in shattered steel box numbed by noise of bombing. I was sleeping fitfully, almost despairing, woken every few minutes by the Scumbarda battery blazing away to keep Jerry awake, and reflected I was living worse than a tramp, absolutely filthy. Unbathed for eight days, clothes not off, ditto, gradually losing all gear, and no home—choice either crowded, dusty, smoky, overcrowded tunnel on hill or overcrowded Iti [Italian] naval headquarters, where Itis having nothing else to do but rush in and out, although bombers miles away. Then wake with start to find a destroyer alongside, and troops slid down chute, scrambled down ladders, ammo dumped ashore. “Well done, arrival of these troops should make all the difference.”

Such were the candid, if dismal, impressions of Leonard Marsland Gander, the only Allied war correspondent on the Greek island of Leros during a five-day battle for its control, as recorded in his notebook on Nov. 15, 1943. Whomever Gander quoted regarding the landing of British reinforcements was overly optimistic. They would make no difference whatsoever.

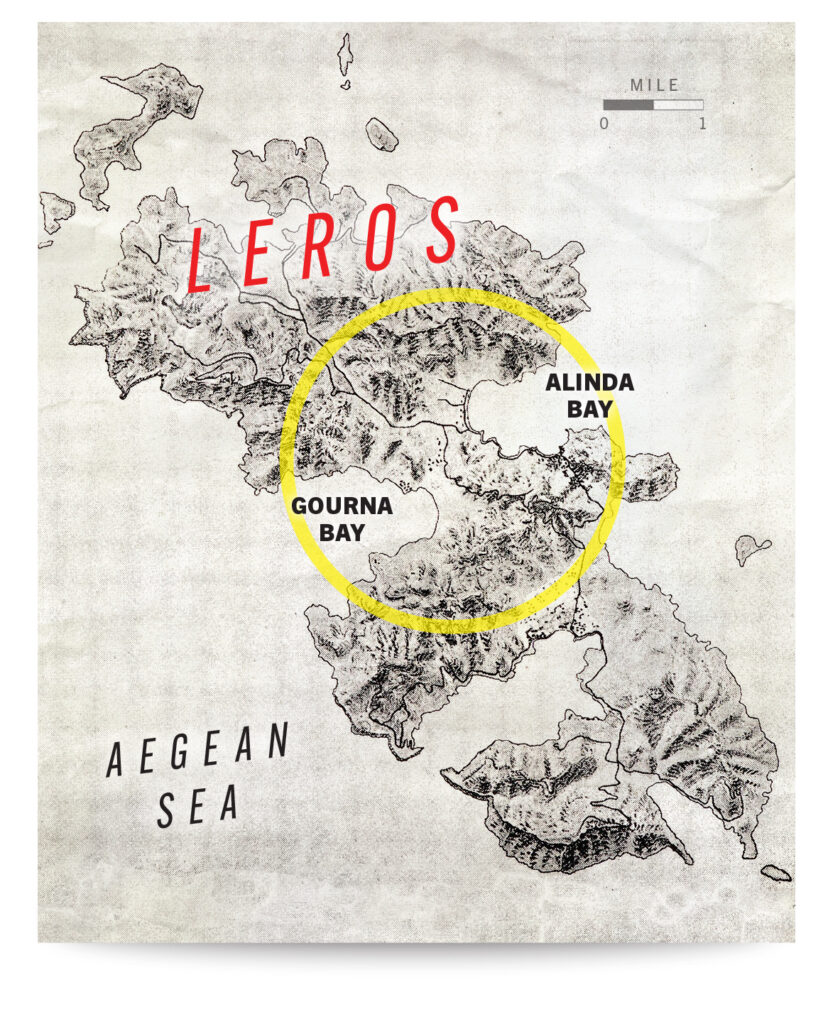

Leros is one of 15 main islands among 150 smaller ones that constitute the Dodecanese archipelago in the southeastern Aegean Sea, which in the fall of 1943 was the unlikely setting for a series of air-sea landings by German forces. Two months later defending British troops were subjected to a humiliating defeat, with some islands remaining under German occupation until war’s end in Europe. The story of their capture is illustrative of history echoing as seemingly no one in authority listened.

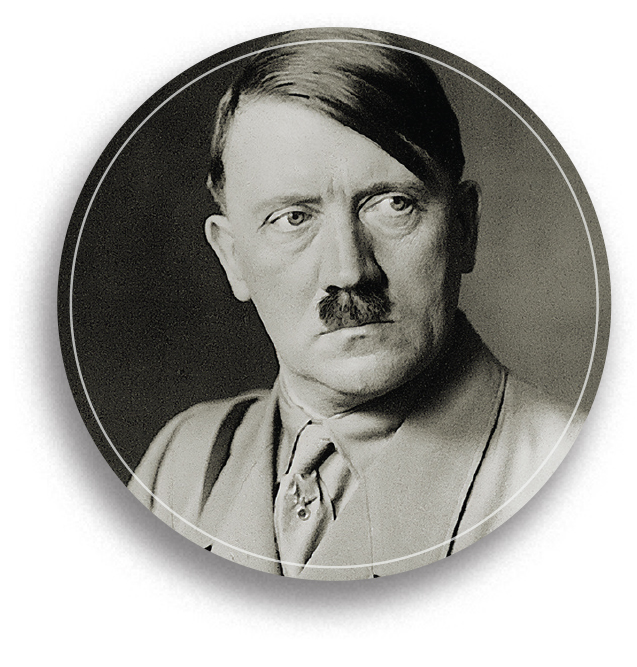

The Dodecanese, populated mainly by residents of Greek extraction, fell under Ottoman rule in the 16th century. The islands then came under Italian administration in the wake of the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–12. In the early stages of World War II Il Duce Benito Mussolini joined forces with German Führer Adolf Hitler, the latter seemingly unstoppable in his occupation of neighboring countries. By the spring of 1943, however, the Axis was faltering. The Soviets had stemmed the German advance into Russia, and that May Axis forces surrendered in North Africa. Soon after, the Allies landed in Sicily and on the Italian mainland, and American-led forces began pushing north toward occupied Europe. In July the Italian populace turned against Mussolini, replacing him with Maresciallo Pietro Badoglio. An armistice followed in September.

Having anticipated events, Hitler initiated Fall Achse (Operation Axis) to forcibly disarm Italian forces and assume control of the territory they held.

Given the upheaval, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill considered it an opportune time to open a new front in the eastern Mediterranean. He and others felt such a move would add to the mounting pressure against Germany and might even encourage Turkey to join the Allies. It was a strategy fraught with impediments and considered by many—Britain’s American allies in particular—a waste of time and resources. Churchill was undeterred.

Paramount to his plan was the seizure of Rhodes with its critical airfields. Italian co-operation was essential. Accordingly, a military mission was tasked with preparing the way for the main assault. Commandos of the British army’s Special Boat Section (SBS) would spearhead the occupation of other islands. Churchill approved the plan on September 9. “This is a time to play high,” he wrote. “Improvise and dare.”

Unfortunately for the British, their invasion plans were pre-empted that very day when the 7,500-strong Sturm-Division Rhodos turned on their erstwhile allies and wasted little time in taking control of Rhodes. In so doing the Germans captured some 40,000 Italians, thus quashing British hopes of significant Italian assistance in the Dodecanese. Nevertheless, there was optimism in the British camp they might still occupy and retain some of the lesser islands. Kos, Samos and Leros were duly secured and garrisoned, primarily by troops of the newly re-formed 234 Infantry Brigade, the battalions of which had arrived in the Middle East after having endured the 1940–42 siege of Malta. Also manning some of the island outposts were detachments of the SBS and the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG). Already on Kos were 3,500-plus cooperative Italians, including the majority of two infantry battalions.

Of the British-occupied islands only Kos was suitable as an airbase. Soon arriving on-island were Supermarine Spitfire VBs of No. 7 Squadron of the South African Air Force and No. 74 Squadron of the Royal Air Force, with some 500 ground support personnel. Anti-aircraft defense was provided by army and RAF gunners equipped with 40 mm Bofors and 20 mm Hispanos, respectively. The British also garrisoned the island with 700 soldiers—mainly of 1st Battalion, the Durham Light Infantry—to counter any German landing attempts. Troops were dispersed between the main airfield at Antimachia and in and around the town of Kos. On the eve of battle some 100 troops of the RAF Regiment arrived as reinforcements.

In mid-September 1943 the Germans in central Italy were forced to pull back in the wake of the successful Allied landing at Salerno. But the situation in the southeastern Aegean was altogether different.

On September 23 Generalleutnant Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, commanding 22 Infanterie-Division, received orders to seize Kos and Leros. Müller made Kos his first objective, targeting it with a combined sea and airborne assault code-named Unternehmen Eisbär (Operation Polar Bear). At his disposal were transport ships and landing craft, air transports, bombers and all-important fighter cover. Additional landing forces included Luftwaffe paratroopers and paratroopers and other units drawn from the special forces Division Brandenburg.

At 0500 hours on October 3 Müller launched Eisbär, the first wave of assault troops coming ashore at Marmari beach in northern Kos. Further landings followed along the rugged southeast coast. Shortly after 0700 hours the Brandenburg paratroopers dropped in on southwest Kos. The Germans rapidly pushed toward their objectives, overrunning each in turn and arriving on the outskirts of town by dusk. That night demoralized remnants of the British garrison withdrew south to high ground. All that remained for the Germans the next day was a mopping-up operation. For the Italians it represented the latest in a series of defeats. But for the British it was a disaster, for without Kos there was no longer any possibility of providing crucial air support for those islands still in British hands.

The Germans next turned their attention to Leros. On September 26 Luftwaffe aircraft began targeting key installations and shipping at Portolago (present-day Lakki). The commander of the British 234 Brigade, Maj. Gen. Francis Gerard Russell Brittorous, had previously commanded the 8th (Ardwick) Battalion of the Manchester Regiment (Territorial Army) in Malta. Known for his punctilious observance of parade ground discipline, “Ben” Brittorous was an unpopular officer. On one occasion, as he rode in his jeep past a number of LRDG men on a break from training, he harangued them for having failed to salute him. According to one present, the general was apoplectic. “So you think yourselves tough, do you?” Brittorous hollered. “I’ll bloody well give you something to be tough about!”

Shortly afterward Captain John Olivey and 48 other LRDG troops left Leros in a pair of Italian speedboats with orders to occupy the tiny German-held island of Levitha, little more than 20 miles to the southwest. It was an ill-conceived and hastily conducted operation, launched without reconnaissance or preparation. Five LRDG men were killed during the failed assault, while most of the remainder were captured. Only Olivey, a fellow officer and five others made it back to Leros.

Eventually, a senior officer was sent on a pretext to British headquarters in Cairo to report on the relationship between Brittorous and subordinates, and on November 5 Brigadier Robert “Dolly” Tilney arrived on Leros as the new fortress commander.

POW Tag

Emblematic of the failed 1943 Allied campaign to seize the Italian-held Dodecanese islands in the wake of Italy’s signing of an armistice is the above German-issued POW identification tag. Most Allied prisoners spent the duration of the war in camps in Germany.

By then there was a substantial British presence on the island, including 2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers (the Faughs); Company B of 2nd Battalion, Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment (the remainder of which was on Samos); 4th Battalion, Royal East Kent Regiment (the Buffs); and 1st Battalion, King’s Own Royal Regiment (Lancaster), plus artillery and supporting sub-units and detachments of the LRDG and SBS. The British garrison comprised some 3,000 troops of all ranks.

The Italian garrison numbered some 5,500, including an infantry battalion, two heavy machine-gun companies and part of a maritime reconnaissance squadron.

Müller’s assault on Leros, code-named Unternehmen Taifun (Operation Typhoon), commenced early on November 12. The assault force was split into three. The initial wave comprised four seaborne Kampfgruppen (combat groups) and a Luftwaffe parachute battalion. A second wave stood by with anti-aircraft and artillery units and heavy infantry weapons. Additional troops and Brandenburg paratroopers were held in reserve near Athens. (On November 13 the Brandenburg Fallschirmjägerkompanie would conduct its third operational jump within six weeks.)

It had been Müller’s intention to land each group simultaneously and seize control of central Leros before its garrison could react. But unforeseen circumstances and a determined resistance meant only certain elements of the invasion force made it ashore, and not all of them at their intended points. At around 1430 hours on the 12th German bombers and cannon-armed floatplanes escorted inland more than three-dozen Junkers Ju 52/3m transports carrying Kampfgruppe Kühne. Hauptmann Martin Kühne’s 470 paratroopers immediately established themselves in and around the central drop zone between Gourna and Alinda bays. In the north infantrymen led by Major Sylvester von Saldern quickly achieved their objectives and held, albeit temporarily, the high ground on and around the dominating Clidi feature to within 500 yards of the coast at Alinda Bay. Having established themselves in central Leros, the Germans had effectively divided the island in two.

Fighting continued for five days, each side losing and retaking ground in a series of seesaw actions. Meanwhile, the British ferried in additional Royal West Kents from Samos, and the Germans also brought in reinforcements. Despite their superior numbers, the British were greatly disadvantaged without air cover, while the Germans had Junkers Ju 87D-3 Stuka dive-bombers on call from dawn till dusk.

Both sides suffered from inadequate signaling equipment. The Germans sought to overcome that issue by adhering to their original plan, whereas the British seemed unable to cope, constantly having to adapt to the changing situation, using runners to try to maintain contact. Invariably, messages got through too late, if at all. Officers received conflicting and confusing orders, and men were flung into the attack, sometimes with little or no idea of their objectives. British communications eventually broke down altogether, and with it evaporated what remained of command and control.

On the morning of November 16, with the Germans on the verge of overrunning brigade headquarters on Mount Meraviglia, Tilney withdrew with his staff, hoping merely to shift his command post south to Lakki.

At 0825 hours the Germans intercepted a signal from fortress headquarters to general headquarters in Cairo. It advised the situation was critical; German forces supported by Stukas and machine-gun fire were reinforcing the Leros peninsula, and defensive positions on Meraviglia had been neutralized, leaving British troops demoralized and facing a hopeless situation. The message was translated, duplicated in leaflet form and airdropped over German positions with additional words of encouragement from Müller: “Now, let’s finish them off!”

But Meraviglia’s defending troops managed to stem the German advance, encouraging Tilney to return and try to restore order from chaos. It was hopeless. That afternoon a renewed German effort resulted in the capture of Tilney and staff. Elsewhere, British soldiers unaware of developments felt they held the upper hand, an opinion shared by many of those opposing them. The brigadier, however, concluded further resistance was futile and, to avoid further unnecessary bloodshed, called for an end to the fighting.

Samos, the final obstacle to Germany’s conquest of the Aegean, was abandoned by the British and fell without a fight on November 22.

Müller reported German casualties during the battles for Kos and Leros as 1,168 dead, wounded and missing, though actual figures are probably higher. The Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe also incurred considerable material losses during the two-month period of operations.

Allied losses tallied more than 5,000 army personnel (most of whom were captured), 500 naval personnel killed or missing and further losses among aircrews. The Germans had sunk three Allied submarines, 15 ships and various other craft, and damaged at least 10 other vessels. The Allies also lost more than 100 aircraft, including 11 American planes, with 28 more damaged.

The Italians suffered most of all. Of nearly 4,000 mainly Italian prisoners of war aboard the German-operated transports Gaetano Donizetti and Sinfra, some 3,400 went down when both ships were sunk that fall in separate Allied actions. Many more were lost while in transit outside Aegean waters.

In the end the Dodecanese mattered little, if at all, in the bigger picture. Anticipating the inevitable backlash from critics, Churchill recommended the foreign secretary adopt an evasive policy when the matter was raised in Parliament: “Not advisable to reflect in detail on such questions as to why the lessons of Crete in 1941 had not been learned.”

On November 20 the Cairo-based Egyptian Mail headlined events in Russia. Four days earlier, before Tilney’s surrender on Leros, correspondent Gander had been evacuated.His report on the island’s capture made P. 2 of the Mail.

Anthony Rogers is the author of several books about wartime events in and around the Mediterranean, including Churchill’s Folly and Swastika Over the Aegean. For further reading he recommends War in the Aegean: The Campaign for the Eastern Mediterranean in WWII, by Peter C. Smith and Edwin R. Walker.

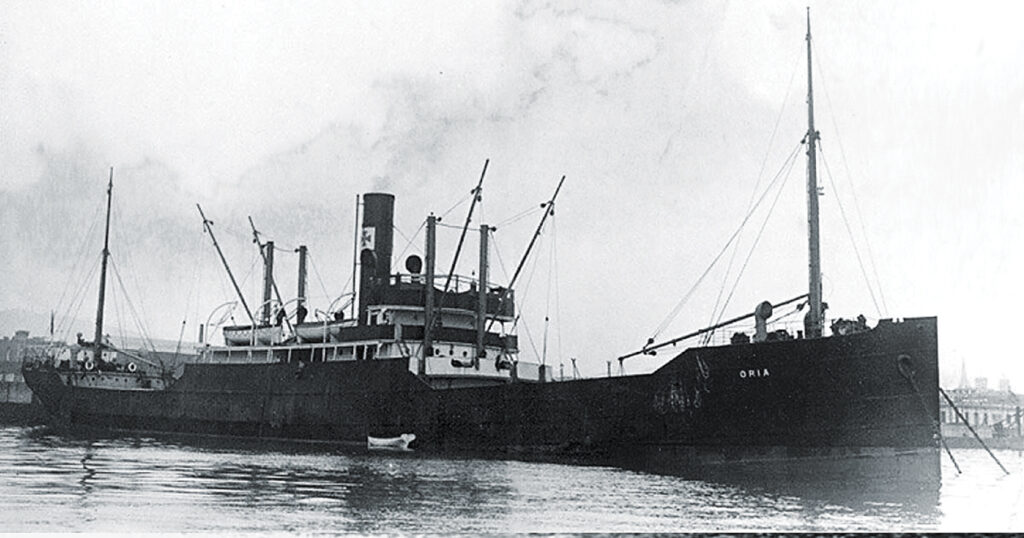

The Loss of Oria

A tragic irony of the Italian armistice is that so many of the nation’s captured and surrendered troops failed to make it home alive. More Italians perished while in transit to destinations in the Reich than died fighting in the Dodecanese.

On Feb. 11, 1944, German guards on Rhodes crammed more than 4,100 Italian prisoners aboard the commandeered Norwegian steamship Oria for passage to Piraeus, Greece. A victim of rough seas and, it is suspected, poor navigation, Oria ran aground the next day off Patroklos,

an island in the Saronic Gulf some 25 miles southeast of Piraeus. The ship foundered, taking with it nearly all the passengers and crew. The Kriegsmarine initially reported that only the ship’s captain and 14 Germans had been saved. Later estimates suggest 21 Italians also survived the sinking, which ranks among the worst maritime disasters in modern history. —A.R.

This story appeared in the Autumn 2023 issue of Military History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.