On an early April day in 1926, Il Duce Benito Mussolini stepped forward to salute an animated throng of people outside the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome.

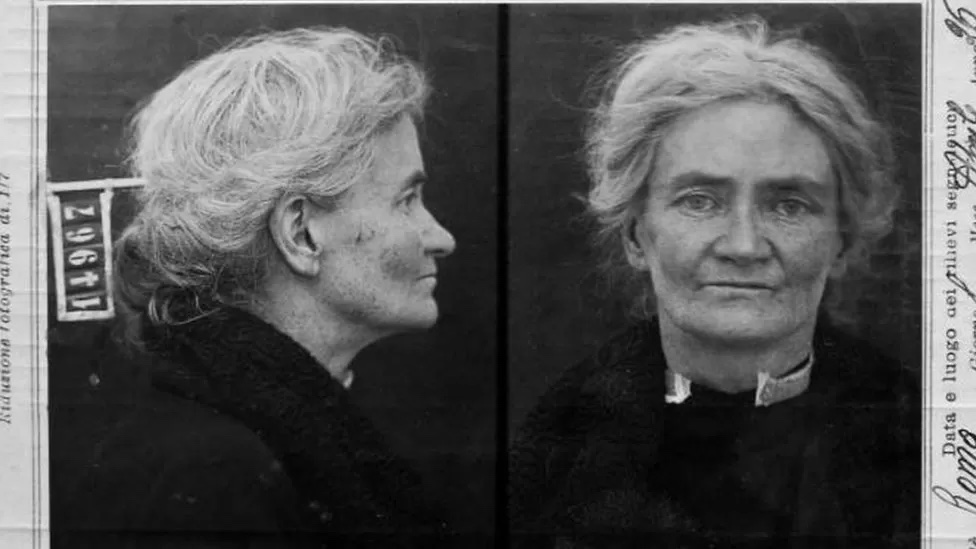

Among the adoring crowd, however, was 50-year-old Violet Gibson, an Anglo-Irish woman who was less than enthused with the Italian fascist dictator.

In Mussolini’s lifetime, four people managed to launch assassination attempts against the dictator. But just one of them, according to the Smithsonian, ever came close to succeeding.

Gibson came the closest.

Born in 1876, Gibson hailed from Irish aristocracy — her father, 1st Baron Ashbourne, served as Lord High Chancellor of Ireland from 1885 to 1905 and was a close friend of the British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, according to The Irish Post.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

The young Gibson divided her time between Dublin and London and was a debutante in the court of Queen Victoria at the age of 18.

Despite her status, Gibson was described as a sickly girl who often “suffered from scarlet fever, pleurisy and bouts of so-called ‘hysteria,’” wrote The Irish Post.

In 1922, at the age of 46, she suffered a nervous breakdown and was committed to a mental asylum. She was released two years later and traveled to Rome with her live-in nurse, Mary McGrath, to join a convent.

“While in Italy, her mental state unraveled further, as she became engrossed in esoteric religious and philosophical currents, including mortification and theosophy, and was convinced that God wanted her to commit a sacrificial murder,” according to the Post.

Gibson also came to believe that she should be the victim of that murder, and in February 1925, she fired a pistol into her chest.

Miraculously, she survived.

After she recovered, Gibson refocused on her morbid quest, setting her sights on a new target: Mussolini.

The opportunity came April 7, 1926, as Mussolini walked through a crowd of supporters after giving a speech to a conference of surgeons in Rome. While walking through the square, Il Duce came within mere feet of Gibson when the small, “disheveled-looking” woman removed a revolver hidden within a black veil “and fired at him at point-blank range,” Siobhán Lynam, a producer who created a radio documentary on Gibson, told The World.

As luck would have it, at the exact moment Gibson fired her weapon, Mussolini turned his head — his attention turning to a group of students who were singing a song in the dictator’s honor.

Instead of striking him square in the face, the bullet grazed the bridge of his nose, sparing his life.

Gibson tried to shoot him again, but the gun misfired.

She was then dragged down by a mob and beaten severely until the police escorted her away.

Mussolini was quickly treated and even rejoined the crowd. Sporting a bandage across his nose, he told supporters that the attack was “a mere trifle.”

Gibson’s embarrassed family wrote to the Italian government, apologizing for her actions.

Mussolini declined to press charges, and his would-be assassin was deported back to England. Once there, Gibson was diagnosed as a “chronic paranoiac” and sent to St. Andrew’s Hospital where she lived out her days until her death in 1956 at the age of 79.

No family members attended her funeral.