On the afternoon of May 11, 1943, the gray hulks of Type II Hunt-class British Royal Navy destroyers sliced through the glistening Mediterranean waters in the narrow Strait of Sicily, their officers scanning the nearby Tunisian coastline.

Lieutenant Commander Richard Rycroft, the 31-year-old captain of HMS Tetcott, trained his binoculars on Kelibia, an idyllic Tunisian fishing town on the Cap Bon peninsula founded by the Carthaginians in the 5th century bc as the fortified town of Aspis. Millennia after a Romans fleet besieged Aspis in 255 BC amid the First Punic War, warships had returned to Kelibia’s coastline. Rycroft spotted his prey and directed Tetcott toward a small boat filled with fleeing Germans. The few enemy soldiers posed little threat, but the British destroyer, its bow surging through the azure water, showed no signs of slowing. As it sped past the enemy vessel, the ship’s log noted, Tetcott “lobbed a depth charge close to it, blowing it to bits.”

Rycroft’s cold efficiency at the helm of Tetcott was not unique. A day earlier Lt. Cmdr. John Valentine Wilkinson, commanding HMS Zetland, had received orders to investigate enemy boats sighted in the Gulf of Tunis and found three rafts carrying 30 Axis soldiers. The destroyer charged the small craft, and “the boats were rammed or capsized and rendered unserviceable.” Wilkinson’s report, like Rycroft’s, made no mention of survivors plucked from the sea.

Yet such actions were not random bloodlust on the part of the British captains. This was their retribution.

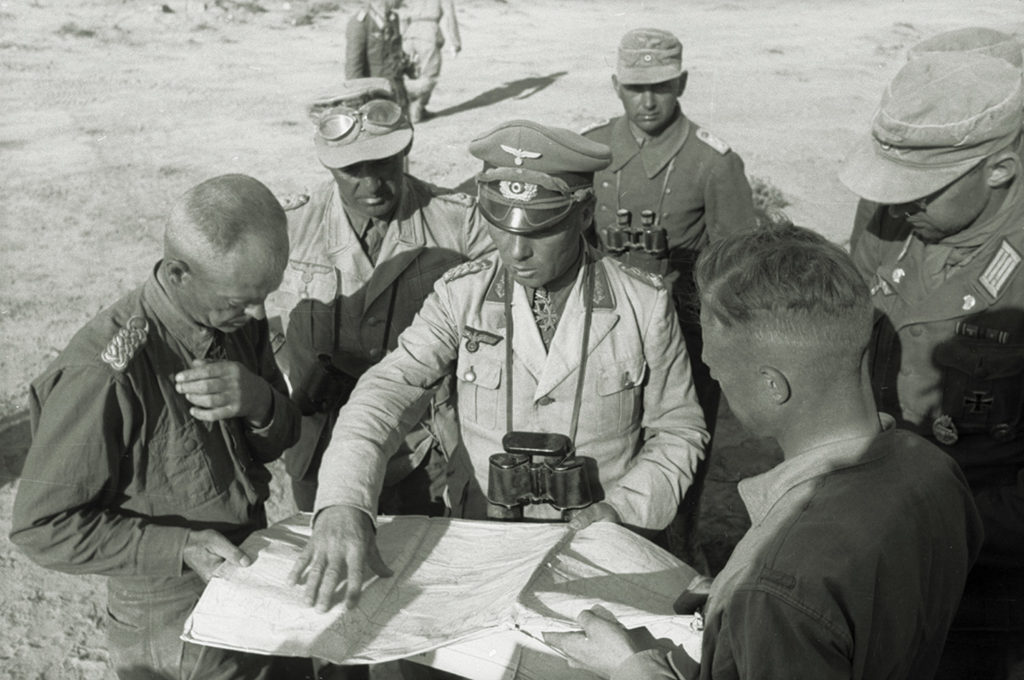

Operation Retribution was the purposefully named Allied air and naval blockade intended to thwart the evacuation of enemy troops from Tunisia to Sicily. The war in North Africa was grinding to a close. Anglo-American forces that had come ashore during Operation Torch—the November 1942 landings in Vichy French–ruled Morocco and Algeria—were closing in from the west, while British Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army, the victors of El Alamein, approached from the south. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the famed “Desert Fox,” and his vaunted German-Italian panzer army were trapped in an ever narrowing vise. Their only means of reinforcement or escape was the tantalizingly narrow Strait of Sicily.

Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Browne Cunningham, the unwavering commander of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, understood both the emotional and strategic importance of the blockade. On May 8, 1943, Cunningham officially launched Retribution with an order Nelsonic in its simplicity and unequivocality: “Sink, burn and destroy. Let nothing pass.”

Only five days later, on May 13, the operation was over. Despite its chilling name, however, its scorecard lacks distinction. Cunningham’s warships encountered few blockade-runners and no major evacuation effort. British sailors captured just shy of 900 fleeing enemy soldiers. The Allies suffered few casualties, and their ships came under serious attack only accidentally from friendly aircraft. The blockade did manage to bottle up more than a quarter million Axis troops—exceeding the number taken after the pivotal battle of Stalingrad—but their surrender was received by the advancing land armies. With few casualties and prisoners, Retribution faded from the story of World War II.

However, such numbers and the official dates of Retribution fall woefully short of relating the complete story of the blockade. From November 1942 onward the Axis desperately tried to resupply its beleaguered armies in Africa. In response Cunningham’s destroyers, motor torpedo boats and submarines fought for control of the sea lanes to Sicily, resulting in a bloody clash of naval forces that stretched five months, until early May 1943. As Cunningham noted in postwar correspondence, “Our main naval effort [in early 1943]…was against the enemy’s lines of communication between Sicily and Tunisia…interrupting the enemy’s supplies to North Africa.” It was those earlier efforts that had bought the relative quiet during the five days of Retribution. For the battered sailors of the Mediterranean Fleet it was an emotional victory. On a grander scale, Retribution was the culminating victory for the Allies in North Africa.

For German-Italian forces in North Africa the closing weeks of 1942 marked a time of defiance. With short supply lines from Sicily and a compact defensive position, Axis commanders planned to create an impregnable Tunisian stronghold. “Any hope for an Axis victory in Tunisia,” notes naval historian Barbara Brooks Tomblin, “depended on the volume of men and supplies that could be delivered by the Italian navy or Axis air forces.” Grand Adm. Erich Raeder, the German naval commander in chief, believed “the decisive key position in the Mediterranean has been and still is Tunisia.” Wehrmacht chief of staff Alfred Jodl concurred, writing, “North Africa absolutely must be held as a forefield of Europe.” Having deemed Tunisia the “cornerstone of our conduct of the war on the southern flank of Europe,” Adolf Hitler ordered its defense at any cost. Thus supported by his advisers, the Führer, in the words of German historian Horst Boog, turned “Tunis into an existential question” and rushed reinforcements to the theater.

The Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet was equally defiant. Six months before formally ordering Retribution, Cunningham sent Force Q—a flotilla of three cruisers and two destroyers under Rear Adm. Cecil Harcourt—to the port of Bône, Algeria, with clear instructions to cut off Tunisia. Foreshadowing the ruthlessness to be exhibited that spring, Force Q gave the enemy “every reason to dread the night attacks,” as Cunningham later wrote:

At about half an hour after midnight on December 1st–2nd these ships [Force Q] fell upon the convoy [Italian Convoy H] off the Gulf of Tunis, and for the enemy it was a holocaust. Engaged at point-blank range, four supply ships or transports and three destroyers were sunk or set on fire. It was a ghastly scene of ships exploding and bursting into flame amidst clouds of steam and smoke; of men throwing themselves overboard as their ships sank; and motor vehicles carried on deck sliding and splashing into the sea as vessels capsized. What men the enemy lost, what quantities of motor transport fuel and military supplies were destroyed, I do not know; but not one ship of that convoy survived.

Several Italian escort ships did survive, but Force Q sank all four troopships of the enemy convoy in what history records as the Battle of Skerki Bank.

Over the following weeks and months British torpedo boats out of Bône and Sousse, Tunisia (south of Cap Bon), “were a constant menace to the Axis shipping,” Cunningham recalled. “Hardly a night passed but they were off Tunis and Bizerte, mining, harrying the patrols, attacking and sinking vessels carrying the stores, ammunition and petrol so badly needed by Rommel’s army.” Joining in the fray, Allied submarines sank 14 merchant ships, two destroyers, one U-boat and two small vessels in November and December. In the first three months of the new year they added 57 merchantmen, a submarine, a torpedo boat and seven small vessels to their tally of kills.

While relentless, the Allied vessels were hardly untouchable. Working in conditions of extreme hazard, the British submarines suffered especially heavy losses, including Tigris, Thunderbolt and Turbulent in February and March 1943. “[The] destroyers were being used to the limit of their capacity,” Cunningham wrote, and “did not escape unscathed.” Enemy attacks sank Lightning and Pakenham only weeks apart in March and April.

The Axis maintained its air superiority. Enemy aircraft pounded the Force Q base at Bône, which sustained damage from more than 2,000 German heavy bombs in December and January. The cruiser Ajax was severely damaged by a 1,000-pound German bomb, while the minesweeper Alarm was knocked out of the war by an air attack.

Cunningham hardened his heart. After all, such losses were the price of a successful blockade. Those successes mounted quickly. “Liable to surface, submarine and air attacks throughout the whole of their passage,” he noted, the Italian navy lost 485 ships from November to May. Of the 314,000 tons of supplies the Axis sent to Tunisia between December and May, Cunningham’s blockade managed to sink nearly a third. The 200,000-plus tons of supplies that did get through were far from enough, as Axis forces in Tunisia expended that amount in a single month. Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe lost irreplaceable aircraft and pilots. Overwhelmed, the Axis convoys continued only with what historian Donald Macintyre deemed “a dogged persistence and a fatalistic disregard of the facts of the situation.” Facing truly legion dangers, Italian sailors called the Straits of Sicily la rotta della morte (“the route of death”).

Denied its Tunisian stronghold, the Axis abandoned its desperate resupply efforts by early May. Thus it was on May 8 the Mediterranean Fleet’s guns swiveled south to scan the North African coast. The mission was unchanged—thwart enemy use of the Strait of Sicily. But the time had come to exploit the victory won during the brutal months of defensive blockade. Operation Retribution, the offensive phase of the effort, would ensure no enemy troops escaped, thus clinching the greatest possible victory ashore.

In May 1943 the Mediterranean Fleet pivoted to prevent the Axis from carrying out its own version of a Dunkirk-style evacuation. Allied intelligence reported enemy engineers were constructing piers and jetties on Cape Bon. According to his command’s war diaries, Cunningham considered an attempted evacuation probable and expected that “an enemy who was still possessed of a great fleet, a substantial merchant navy and powerful air forces would not abandon his trapped armies.”

Yet no rescuers came. The beleaguered Axis veterans of Tobruk, Gazala and El Alamein were left to their fate. “The sight of those little gray ships of ours off the coast,” Cunningham argued, “prevented any organized attempt at evacuation.” Compared to the Mediterranean maelstrom of the previous months, the official launch of Retribution brought relative quiet.

Acting individually and in small groups, stranded Axis soldiers sought to escape to Sicily aboard pitifully small motorboats and rafts. Cunningham’s orders referred to the May blockade as “the offensive,” and the Mediterranean Fleet acted accordingly. “Beaches where enemy activity is observed should be machine-gunned,” torpedo boat crewmen were instructed. Ships’ logs provide blow-by-blow accounts of the small actions. Noticing enemy soldiers escaping to the small island of Zembra, at the mouth of the Gulf of Tunis, the destroyers Beaufort and Exmoor “circled the island in opposite directions” and sighting “several boats on one beach … shot them up.” Beaufort’s guns then “demolished a few likely-looking outhouses” until a white flag appeared.

No fleeing craft or number of evacuating soldiers was too small a prize. On May 10 the destroyer Lauderdale “picked up four Germans from a small boat” and spent the ensuing days “collecting some more Germans from open boats.” The destroyer Lamerton intercepted “a small fishing vessel…and 17 Italians.” The destroyer Dulverton pulled enemy soldiers from “local fishing boats.” Exmoor stopped “one boat and two floats” from which only one German was recovered. The lack of an organized, large-scale evacuation did not deter the Allied blockading force. As its commander had ordered, the Mediterranean Fleet let nothing pass.

Allied operation code names often seem to lack meaning. For example, Dynamo was the impromptu evacuation from Dunkirk, Crusader was the 1941 relief of Tobruk, and Dragoon was the August 1944 landing in southern France. Standing out for its emotional import and relevance, Retribution was different. Cunningham had deliberately named it thus. After years of struggle and loss, Retribution was indeed intensely personal.

On Cunningham’s mind in particular was the Mediterranean Fleet’s harrowing fights for Greece and Crete. In April 1941 its ships evacuated some 50,000 of the 53,000 British soldiers trapped in Greece, but their rescue came at a heavy price. The fleet lost 26 troop-carrying ships to enemy air attacks, including the destroyers Diamond and Wryneck, both of which were sunk, leaving fewer than 50 survivors of the 800-plus crewmen and troops aboard. During the ensuing Battle of Crete the fleet commander relayed to the Admiralty that “in three days two cruisers and four destroyers were sunk, one battleship is out of action for several months, and two other cruisers and four destroyers sustained considerable damage.

“We cannot afford another such experience and retain sea control in the eastern Mediterranean,” Cunningham added. “Our light craft, officers, men and machinery alike are nearing exhaustion.…They have kept running almost to the limit of endurance.”

A still greater strain followed in late May as the Royal Navy rushed to evacuate troops in the wake of the Allied defeat on Crete. “Our losses are very heavy,” Cunningham reported. “[The battleship] Warspite, [battleship] Barham and [aircraft carrier] Formidable out of action for some months, [the cruisers] Orion and Dido in a terrible mess, and I have just heard that [the cruiser] Perth has been hit today. Eight destroyers lost outright and several badly damaged. All this not counting [the lost cruisers] Gloucester and Fiji. I fear the casualties are over 2,000 dead.” Enemy air assaults were incessant. The admiral expressed anxiety “about the state of mind of the sailors after seven days’ constant bombing attack” For five hours the destroyer Kandahar alone was “subjected to 22 separate air attacks” while rescuing survivors. A lamenting Cunningham was justly proud of his fleet:

It is not easy to convey how heavy was the strain that men and ships sustained.…They had started the evacuation already over-tired, and they had to carry it through under conditions of savage air attack such as had only recently caused grievous losses in the fleet.…I feel that the spirit of tenacity shown by those who took part should not go unrecorded. More than once I felt the stage had been reached where no more could be asked of officers and men physically and mentally exhausted by their efforts and by the events of these fateful weeks. It is perhaps even now not realized how nearly the breaking point was reached. But that these men struggled through is the measure of their achievement.

By the end of the evacuation on June 1 the Mediterranean Fleet’s losses were staggering. Three cruisers and six destroyers were sunk; two battleships, a vital aircraft carrier, two cruisers, two destroyers and a submarine were damaged beyond easy repair; and three cruisers and six destroyers were damaged. Another 32 transport and auxiliary ships were lost. Cunningham’s fleet had suffered tremendously. “The army could not be left to its fate,” the admiral dutifully affirmed. “The navy must carry on.”

Cunningham seethed at the battering his ships and men took off Crete. “The Huns amused themselves for an hour or so machine-gunning the men in the water,” he recalled. “I hope I shall get my hands on a few of them.” In 1943 he got his chance.

“We hoped,” he later wrote of his command, “that those of the enemy who essayed the perilous passage home by sea should be taught a lesson they would never forget.” When one destroyer commander apologized that it had been “too dangerous to stop and pick up one boatload [of enemy soldiers], so he ran over them,” Cunningham “shook him warmly by the hand and left him without enquiring further.” Retribution was Cunningham’s duty, but it was also a satisfying score to settle for earlier losses.

“There is no doubt that the blood of the Mediterranean Fleet was up,” remarked Capt. Angus Nicholl of the cruiser Penelope, “and that even the smallest attempts at a ‘Dunkirk evacuation’ were efficiently and ruthlessly dealt with.” When a half dozen German torpedo boats opened fire on the Force Q destroyers Laforey and Tartar, the former rammed one of the enemy vessels, cutting it in half. The lethal resolve of the British fleet was all too apparent to its Axis foe. Lamerton’s radiomen, listening to enemy chatter, overheard, “Destroyer overtaking…all is lost.”

But the conduct of the operation did not reflect mere brutality. Like their commander, the officers and sailors of Cunningham’s fleet viewed Retribution as both their duty and just vengeance. One young lieutenant recalled that when he requested permission to fire on an enemy vessel, his senior officer assented, saying, “It’s your retribution.” A sailor aboard the cruiser Aurora proudly wrote home to his mother: “I’ve always wanted to get even with the Jerries for the hell they used to give us every night.…I felt pretty proud myself…and didn’t the lads stick their chests out.”

The Mediterranean Fleet savored its victory. Captain Tony Pugsley of the destroyer Jervis whimsically reported the seizure of 96 “entrants” from the “Kelibia Regatta,” while Capt. John Eaton of the destroyer Eskimo crowed how the fleet had “strongly discouraged enemy yachtsmen.” Even Cunningham revealed his pleasure, writing, “I trust the boating activity is being firmly stopped.” Others’ appetite for vengeance went unsated. An officer of the 7th Motor Torpedo Boat Flotilla was “disappointed that the enemy did not attempt a mass evacuation.” Rear Adm. Arthur Power agreed. “The complete absence of any Axis men of war or shipping,” he wrote from Malta, “was very disappointing.”

Although disappointing to some, the quiet consummation of Retribution in May 1943 represented ultimate victory for the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet. From the outset of the war the fleet’s priority had been to establish control of the sea. As pioneering British naval historian and geostrategist Sir Julian Corbett wrote, “The object of naval warfare must always be directly or indirectly either to secure the command of the sea or to prevent the enemy from securing it.” His American counterpart Alfred Thayer Mahan similarly argued sea power was “the possession of that overbearing power on the sea which drives the enemy’s flag from it.” In the spirit of these two titans of naval thought, Retribution closed the Mediterranean to the enemy.

Even as the Mediterranean Fleet endured the Battles of Greece and Crete, Prime Minister Winston Churchill joined the Admiralty in reminding Cunningham, “Above all, we look to you to cut off seaborne supplies from the Cyrenaican ports and to beat them up to the utmost.” Though the fleet was stretched thin, losing ships and men, its priority remained the blockade of North Africa.

By May 1943 the Axis navies were wholly unable to move anything across the Strait of Sicily, neither supplying nor evacuating their soldiers and equipment stranded in Tunisia. The vengeance-seeking ships of the Mediterranean Fleet diligently hunted down even the smallest rafts and boats. As Tetcott and Zetland proved off Kelibia, nothing would pass.

For his illustrious half century career Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Browne Cunningham earned a place in London’s Trafalgar Square, the symbolic heart of the British empire. It is Retribution that largely justifies the proximity of the admiral’s bust to Nelson’s Column. At Aboukir Bay in 1798 legendary Rear Adm. Horatio Nelson did not receive the surrender of an enemy army; French forces were already ashore in Egypt. Yet Nelson’s naval victory secured control of the Mediterranean, thus ensuring the ultimate defeat of Napoléon Bonaparte’s Egyptian expedition. Likewise, Cunningham did not receive the Axis surrender in 1943, but his choking blockade enabled victory on land. Retribution, like Lord Nelson’s Battle of the Nile, projected sea power far inland. Fulfilling Churchill’s belief that “much if not most of the navy’s work goes on unseen,” when the German-Italian army in North Africa surrendered, the reward of the Mediterranean Fleet’s tireless efforts was collected in the desert.

As commander of Allied forces in North Africa, Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower summarized the 1943 operation. “The total enemy shipping and craft which offered themselves as targets for the [Royal] Navy seemed a poor reward for its skill and untiring vigilance,” he wrote. “Retribution, in fact, developed into a situation where only isolated small parties of stragglers sought safety by sea, to find that the sea was not theirs.” By then the sea belonged to Cunningham’s Mediterranean Fleet.

Washington, D.C.–based Peter Kentz holds history degrees from Georgetown University and King’s College London. For further reading he recommends With Utmost Spirit: Allied Naval Operations in the Mediterranean, 1942–1945, by Barbara Brooks Tomblin; The Battle for the Mediterranean, by Donald Macintyre; and A Sailor’s Odyssey, by Andrew Browne Cunningham.