Francis McCullaugh (1874-1956), born a British subject in Omagh, County Tyrone, Ireland, was a prolific journalist, author, and war correspondent, principally but not exclusively for James Gordon Bennett Jr.’s New York Herald. Active during the first third of the 20th century, McCullaugh apparently did not shy away from getting close to the fighting.

He personally covered—and usually then published books about his experiences—numerous worldwide hotspots: the 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War alongside Russian troops (With the Cossacks, 1906); unrest following the Russian Revolution of 1905 (New York Times feature articles, 1906); the 1908-1909 Ottoman Empire’s Young Turk Revolution and Abdication of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (The Fall of Abdul Hamid, 1910); the 1911-1912 Italo-Turkish War in Tripoli (Italy’s War for a Desert, 1912); the 1918-1922 Allied Siberian Intervention in the Russian Civil War (A Prisoner of the Reds, 1921); the 1926-1929 Cristero War in Mexico (Red Mexico, 1928); and the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War (In Franco’s Spain, 1937).

Taken Prisoner in Siberia

Perhaps the Irishman occasionally got a little too close to the action: he was made a prisoner of war by the Japanese in March 1905, and was taken captive by Bolshevik Red Army forces in Siberia during the Russian Civil War. Nevertheless, McCullaugh lived until age 82, passing away in White Plains, New York, in 1956.

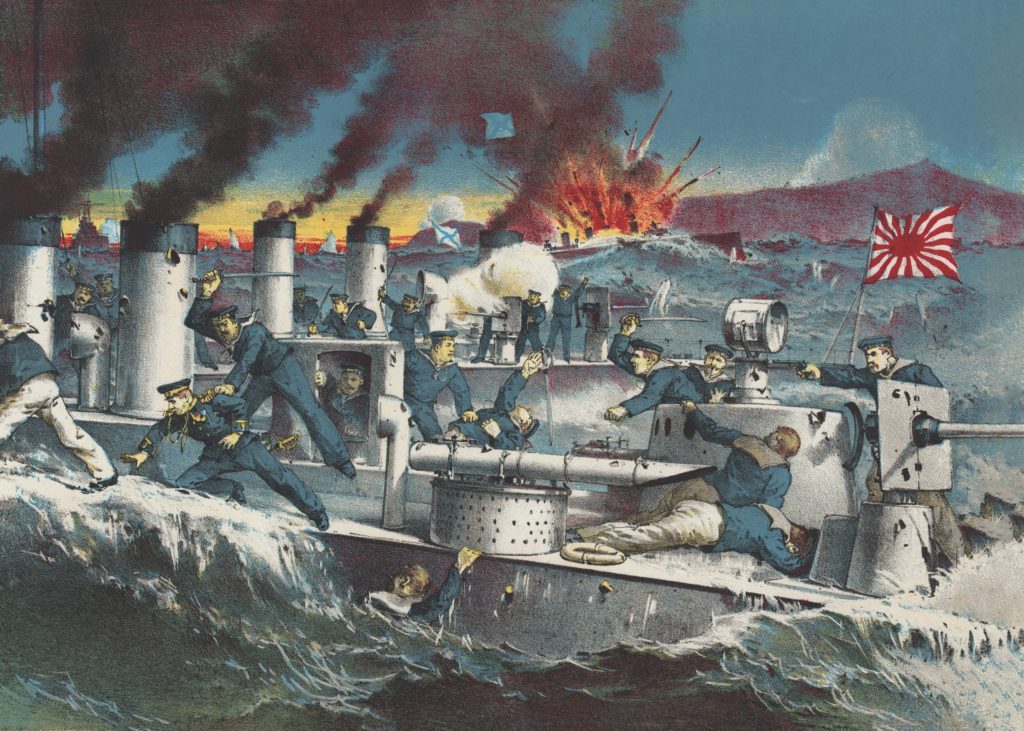

The genesis of the following classic dispatch was in late 1903 while McCullaugh was living in Japan and working for an English-language newspaper, The Japan Times. Realizing the ever-increasing likelihood of war breaking out between Japan and Russia over both nations’ competing claims in Manchuria and Korea, McCullaugh responded by studying the Russian language, relocating to Port Arthur (today, Lüshun Port, China), and securing a job with the Russian newspaper, Novi Krai (New Land). Port Arthur, leased from China by Russia, was then the major Russian naval and military base in the Far East, home port to nearly 50 vessels of all sizes (battleships, cruisers, torpedo boats, gunboats, minelayers) of Russia’s Eastern Fleet (1st Pacific Squadron and some warships from Vladivostok’s Siberian Military Flotilla).

To Japan, Port Arthur, therefore, was an inviting target, and a surprise Japanese naval attack (without a prior formal declaration of war—sound familiar?) the night of February 8-9, 1904, initiated the Russo-Japanese War. McCullaugh quickly parlayed his Russian connections into a correspondent’s assignment with the Imperial Russian Army—specifically, accompanying Lieutenant General Pavel Mishchenko’s 7,500-man East Baikal Cavalry Brigade as it moved from Mongolia into Manchuria, fighting not only regular Japanese forces but also encountering Chinese “Honghuzi”—irregular mounted robbers and bandits recruited by the Japanese to harass, sabotage, and attack Russian forces.

The 1904-1905 Russo-Japanese War was not only a stark preview of what the brutal combat nine years later in World War I would be like, it shocked European powers when upstart Japan humiliated the Russian Empire, one of the West’s major powers. The war featured virtually all of the weapons and tactics used later in the Great War: magazine-fed rifles; rapid-firing machine guns; barbed wire; extensive trenches and fortifications; and indirect artillery fire (extended-range artillery using an artillery forward observer, linked to the firing battery via wire or radio communications, to accurately adjust fire onto a target).

Freed from Captivity—And Joining the Cossacks

The war also demonstrated the deadly folly of launching massed, human-wave attacks against positions heavily defended by modern firepower and well-protected by extensive fortifications, a lesson the Russian Army failed to learn in this war and which World War I armies on both sides failed to heed in 1914-1918. Although the bloody land battles fought by Russian and Japanese troops in Manchuria (notably the February–March 1905 Battle of Mukden, involving a total of 600,000 troops and producing 165,000 casualties) caused the war to drag on for 18 months, it began and was settled by naval battles.

The stunning Japanese victory at the Battle of Tsushima Straits in May 1905 sealed Russia’s fate and stands as one of the most decisive naval battles in history. Mediated by U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt, the Treaty of Portsmouth ending the war was signed on September 5, 1905. Roosevelt was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his mediation.

In 1906, after his release from Japanese imprisonment as a POW, McCullaugh published “With the Cossacks: Being the Story of an Irishman Who Rode With the Cossacks Throughout the Russo-Japanese War (London, Eveleigh Nash)”. It is a 400-page book recounting in great detail his experiences accompanying Mishchenko’s cavalry brigade during the several months between his joining and his capture by the Japanese in March.

The book’s Chapter IV, “Mishchenko’s Raid,” describes the cavalry brigade’s ultimately unsuccessful 12-day excursion in mid-January 1905 attempting to destroy millions of rubles worth of Japanese supplies at Yingkou, a Manchurian port city near the base of the Liaodong Peninsula (Port Arthur is at the peninsula’s tip).

The raid failed, and Mishchenko’s cavalry brigade suffered heavy casualties. However, as the brigade of numerous Cossack and dragoon regiments set out on the raid, McCullaugh provided a vivid, highly-detailed, and extremely colorful description of the incredibly diverse collection of nationalities and fantastic array of disparate ethnic groups that then comprised the Imperial Russian Army as a whole.

Certainly, it validates McCullaugh’s claim that “The advance of Mishchenko’s [brigade in] three columns was the best thing from the spectacular point of view which I saw during the war.”

The following is McCullaugh’s account of his adventures and of the diversity he found among the Russian troops. While his writings reflect an admiration for the troops around him, they also reflect his racial and religious prejudices.

In His Own Words

Recommended for you

HUN RIVER, MANCHURIA, Sunday, January 8, 1905—The day before we started [on General Mishchenko’s Yingkou Raid] was the Russian Christmas Day [January 7], which, like good Christians, we observed by eating “kootia” [ceremonial rice dish] and “varenookha” [honey/fruit-infused “moonshine”] and by holding high revel. Strangely enough, it was in the midst of this revel that I first heard of the [January 2] fall of Port Arthur.

Colonel Orloff had ridden in, late at night, and his first words, uttered in a low tone to a brother officer, were “Port Arthur is fallen, is fallen.” But few of the officers and none of the men knew it until weeks had elapsed. Mishchenko had with him, in addition to his twelve regiments [seventy-two cavalry squadrons] of dragoons and Cossacks, twenty-two cannon, that is almost three batteries. Two of these batteries fired melanite [explosive shell], the rest shrapnel. All of them were, of course, horse batteries, six horses pulling each gun. There were, besides, four Maxims [machine guns] with the Dagestan regiment, but these useful little guns were never, I think, used during the advance southward.

We marched in three columns. The right column, which consisted of the Primorsky, Nerjinsky and Chernigovsky Dragoons and the Frontier Guards, was commanded by General [Alexander] Samsonov, and until the main force reached the Taitsze [River] it traversed the west bank of the Liao-ho [River].

The central column consisted of the Zaibaikal [Transbaikal] Cossacks, that is, of the Verkhnyudinsky and Chitinsky regiments, and of the Ural Cossacks. It was commanded by General Abramov, the leader of the Ural Cossacks, and General Mishchenko accompanied it. The left column consisted of the Don Cossacks and of the Caucasian brigade. It was under the command of General Tyeleschov and was followed by the Zaibaikal battery, the soldiers of which bear in front of their black busbies a metallic scroll commemorating their bravery during the [1900] Boxer troubles.

Besides, there was the mounted infantry, a fine body of men who should alone have carried Yingkou station on January 12. As is well known, each Russian regiment of foot has attached to it about one hundred cavalrymen. As, under the conditions which then prevailed at the front, these horsemen were unnecessary there, they were all drafted for the time being into Mishchenko’s detachment, which therefore amounted in all to some 7,500 men. From this force different parties were from time to time detached for the purpose of cutting the railway. The four Maxims went with the Dagestan regiment of the Caucasian brigade, but it was not the Caucasians who were supposed to work these guns. Trained men had been brought from St. Petersburg for that purpose. They were under the command of Captain Chaplin, a promising young officer who had served in the artillery at Warsaw, but who was unfortunately the first man to fall on the occasion of this expedition.

On the afternoon of the first day all our different columns met at a village called Sifontai, east of the Hun River, and what a picturesque gathering that was! When I attempt to catalogue the different forces which composed it, I feel inclined, like Homer, to call upon the daughters of Jove to assist me, for of myself I am not able to do justice to so vast a subject. It was one of the most composite forces that ever met together in Asia, a force worthy of “the mighty behemoth of Muscovy, the potentate who counts three hundred languages around the footsteps of his throne.”

It comprised Buryats, Tunguses, Bashkirs, Kyrgyz, mountaineers from Dagestan, Tartars, Cossacks of Orenburg, Cossacks from the Don, children of the men who had won such victories in Italy under [Alexander] Suvorov, who had captured Napoleon [October 25, 1812, but rescued by French grenadiers] at Maloyaroslavets, who had chased Jerome Bonaparte from his [Westphalian] throne, who had pitched their tents in the Champs-Elysees [1814-1815], Buryats, whose race has produced “the most terrible phenomena by which humanity has ever been scourged . . . the Mongol Genghis Khan,” descendants of the men who had followed the Scourge of God, flat-nosed Kalmyks whose very name recalls that great flight to China which [Thomas] De Quincey has immortalized [Revolt of the Tartars], descendants of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, that semi-religious order of bloodthirsty celibates who made their lair in the islands of the lower Dnieper River. Mishchenko’s force seemed to contain within it all the elements of a Yellow Peril, combined with a faint hint of a Moslem Peril. Their green banners embroidered with red inscriptions in Arabic—all texts from the Koran—the Caucasians rode past on their graceful Arab steeds. Among them was a representative of every race and language in the Caucasus. They were those Mohammedan mountaineers who held Russia at bay for a century. All of them were splendid at single combat, and bore swords of the best tempered steel. The young men were often singularly handsome, with figures like Greek statues, oval heads, bold noble profiles, large dark eyes, delicately chiseled lips, and most murderous dispositions.

It is impossible for me to give an idea of the proud dignity of their bearing, the grace of their movements and the fire of their look. They had got amongst them an extraordinary and valuable collection of fine Circassian swords and daggers, with damascened blades, often inlaid with gold, and always channeled so as to let the blood spurt out. Latin invocations to the Blessed Virgin inlaid in some of the blades seemed to indicate that they had changed hands as often as the poignard [Caucasus stiletto-like dagger] to which [Mikhail] Lermontov devotes one of his poems [“The Dagger” 1838]. The sheaths of their numerous daggers terminated in a metal-drop tip suggestive of blood. Their carabines they carried in covers of sheepskin with the hair outside, and they had also on their stirrups sheepskin covers, which are admirable protections against the cold. Later on, I regretted exceedingly not having got such stirrup-covers myself.

The same thing always happened when a Caucasian mounted his horse. One caught sight of him poised for a moment on one stirrup while the horse reared and pranced; then there was a flop of variegated petticoats, a jingle of spurs, a rattle of weapons, and the rider had tumbled into the saddle and was telling his still prancing steed, in tones with more of admiration in them than of anger, that he “was naughty, very naughty.”

None of those Caucasians spoke any Russian, a fact which detracted seriously from their value as scouts. To make matters worse, there were in our little force of Caucasians about fifteen completely different languages, and it was very seldom that a man spoke more than two or three of those languages at most.

The Russians explained this diversity of tongues by saying that every invader of Europe had passed through the Caucasus, leaving amid these mountains a handful of his people who immediately proceeded to form a new community, until, finally, that country became the ethnological museum it is today.

However they may rank as regular soldiers, there can be no doubt that in private life these Mohammedans are fierce. The first day I spent with them I saw one man draw his sword on another over some dispute about fodder. An officer, who was standing by, wearily told him to put up his weapon. “Reserve it for the Japanese,” he said, and then he resumed an interrupted conversation about the latest opera at Bayreuth.

“I do not know if Russia did a wise thing in sending these men out to Manchuria at all, for if there is any truth in the accusations of barbarity the Japanese have made, these Caucasians must—although nearly all of them are “princes”—have been the guilty parties. They are decidedly picturesque, it is true, but they are not much good against plain unimpressive foot soldiers.

Then again, they came to Manchuria under a misapprehension. They thought the war with Japan would be run on exactly the same lines as the war with China [Russia’s June-November 1900 invasion and occupation of Manchuria]; and they cannot be blamed for falling into this mistake, since their officers also thought so. As soon as they had ascertained that the Japanese were not naked savages, armed with bows and arrows, they got discontented and wanted to go home, but were refused permission to do so, whereupon many deserted and were immediately caught and shot.

The Russian non-commissioned officers amongst these Caucasians belong to the Cossacks of Kuban and Terek, the “line of the Caucasus,’’ names of rivers which recall bloody battles and the memory of the unhappy Lermontov. Up till a short time ago they fought continuously against these fierce Tcherkasses [North Caucasus ethnic group], whose arms and equipment they have adopted, and whose very features they seem to have borrowed—a fact which is explained by a venerable custom these Cossacks still have of massacring all the men in an “aul” [fortified village] and conveying the best looking women to their “Stanitsy“ [Cossack military settlements] in order to marry them.

Like the Transbaikal and unlike the Ural or Don or Black Sea Cossacks, these Caucasians have no lances, but depend altogether on their good sabres. Among them rode the grandson of Imam Schamil [Imam of Dagestan 1834-1859], who within the memory of living men troubled Russia with a guerrilla warfare [during the Caucasian War 1817-1864], which he conducted with a genius and energy scarcely paralleled in history. The St. George’s Cross, which the aged standard-bearer of the Dagestan regiment wore, was won on the day that Schamil surrendered [September 1859].

At the head of the Caucasian brigade was Prince Orbelian, of an ancient Georgian family, which claims to be descended from two Chinese princes who obtained in 240 A.D. the protection of Artaxerxes, whose son Sapor transferred them with their followers to Armenia. Prince Orbelian did not, however, take part in the raid, being sick at Harbin, but his place was taken by an equally picturesque figure, Prince Nakhchivansky, a Mohammedan nobleman.

The names of the officers with whom I rode were all historical. Some of them are borne by the oldest Cossack families—Grekoff, Plaoutine, Platoff, Kaznetzoff, Krasnoff. One young colonel from the General Staff, who accompanied us bore the name of that gigantic barbarian who loved Catherine the Great and who strangled her Imperial husband. He is a polished diplomatist, a great linguist, a landowner, a courtier, an influential man at headquarters. He rode on this occasion a horse which was almost worth its weight in gold, and, according to his invariable custom on such occasions, carried in his pocket a copy of one of Shakespeare’s plays. His knowledge of English literature and of every nuance of expression in the English language is extraordinarily extensive.

The colonel of the regiment to which I was attached was called Bunting, and was of English descent. One of the officers, a polite and well-educated young man from the Guards, was of Tartar descent, as his name, Turbin, indicates. Another was young [Frenchman, Ferdinand] Burtin, at one and the same time lieutenant in the Arab cavalry of France and centurion in the Mongol Cossacks of Mishchenko.

To make our crowd still more variegated, there was a full-blooded negro in it. He had been born in the Caucasus, spoke only Russian, and seemed to be exactly on an equality with his white comrades-in-arms. With the exception of Burtin, I was the only non-Russian at this memorable trysting-place in the valley of the Liao-ho.

However much I might try to persuade myself that the Cossack is a thing of the past, I could not fail to be impressed by this great gathering of the men who guard the Russian frontier from the shores of the Pacific to the shores of the ebony [Black] and amber [Baltic] seas, and whose very designation, recalling the names of great rebels like [Ivan] Mazepa, Stenka Razin, [Yemelyan] Pugachev, the “False Dimitri,” made me see, dimly, gigantic upheavals more Asiatic than European, and made me hear faintly, as at a great distance, the hoof-beats of innumerable hordes of horsemen galloping over the steppes. The Cossacks cannot fail to be interesting, for they are the only reminder we have left of the time when the population of Europe was fluid and nomad.

How many shades of Christianity, Mohammedism, Lamaism, and Buddhism there were amongst us I dared not inquire. When at set of sun I saw the Mohammedan pray with face turned towards Mecca, I felt as if I were in a Turkish army. When I saw the Russian kiss the collection of ikons and crucifixes that he wore around his neck, I felt as if I were among Crusaders. When the indolent Mongol laughed at both Mohammedan and Christian, I felt that I was back in my own century. We were an overflow from the great Muscovite crucible, in which all sorts of strange undigested elements boil and bubble without ever uniting.