Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s South Pacific opened on Broadway in 1949 to immediate acclaim and racked up 1,925 sold-out performances before closing in January 1954. A film adaptation by director Joshua Logan in 1958 brought the show to an even larger audience, cementing South Pacific’s status as one of the greatest musicals ever. Many of its songs have become instantly familiar classics: the bawdy “There is Nothing Like a Dame,” the giddy “I’m in Love with a Wonderful Guy,” and the passionate “Some Enchanted Evening.” But the weakest of its tunes, artistically, is also the most politically powerful, and points toward one of the notable ironies of the American experience during World War II.

Rodgers and Hammerstein based their production on the Pulitzer Prize-winning Tales of the South Pacific (1947) by James A. Michener. Structured as a collection of loosely-related short stories, the book serves as a reflection of the U.S. Navy veteran’s travels throughout the South Pacific as what he called “a kind of superclerk for the naval air forces” during World War II. While it does not possess a uniting theme, a recurrent motif is the way its characters are wrenched from their everyday lives, forcing them to confront inner struggles and limitations they likely could have avoided but for the war.

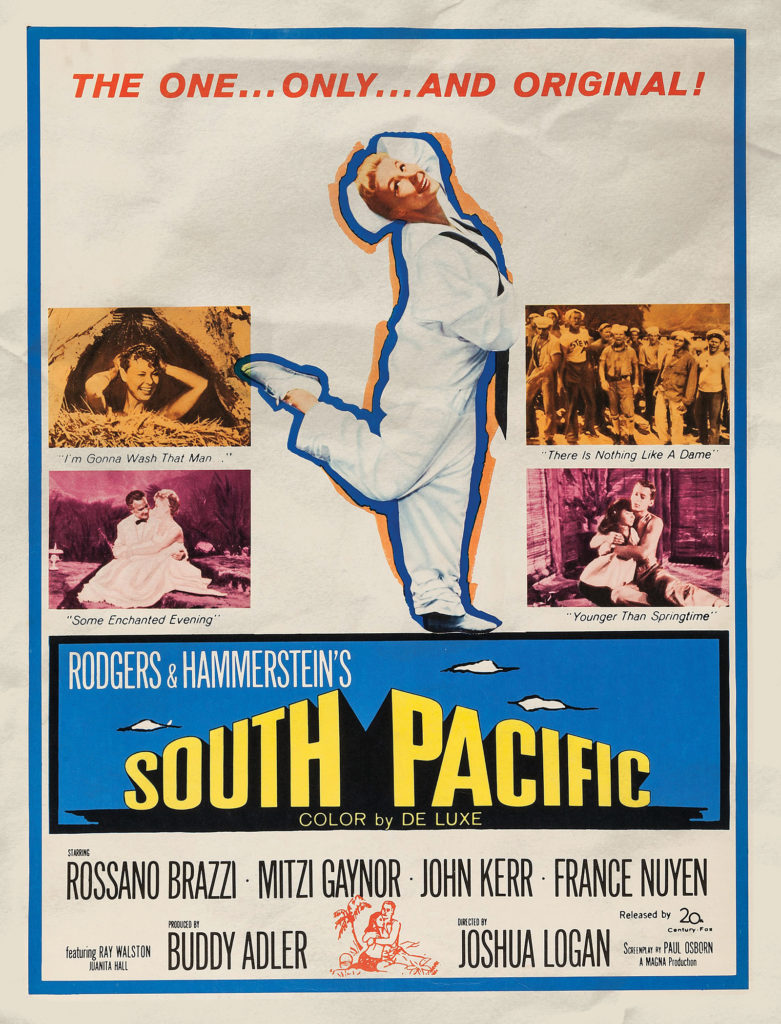

Rodgers and Hammerstein were drawn to two stories in Tales of the South Pacific and turned them into intertwining plotlines. In one, a Marine lieutenant, Joe Cable (played by John Kerr in the film), falls desperately in love with a Polynesian woman, Liat (France Nuyen), but discovers he cannot bring himself to marry her due to her race; in another, Nellie Forbush (Mitzi Gaynor), a navy nurse from Arkansas, falls in love with a French planter, Emile de Becque (Rossano Brazzi), but is then shocked and repelled to discover Emile has a number of mixed-race adult children by Polynesian women. (Both the Broadway and film versions soften Emile’s status to that of a widower with two offspring, both irresistibly cute little tykes.) Michener’s book explores Joe’s story much more deeply than Nellie’s; Rodgers and Hammerstein reverse the emphasis. It nonetheless falls to Joe to explain the roots of their shared racism in a song called “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught.”

“You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” is melodically undistinguished; lyrically it is simplistic and didactic. Several friends of Rodgers and Hammerstein urged that the song be cut—but for its explosive political content, not its artistic limitations. American children, Joe tells the French planter, aren’t born harboring prejudice; prejudice is instilled in them by parents and relatives who teach them to hate and fear “people whose eyes are oddly made” and “people whose skin is a diff’rent shade.”

Today elements of South Pacific itself appear racist, particularly its one-dimensional characterizations of Polynesian individuals as “primitive” and “exotic.” But at the time the show packed a powerful punch, taking direct aim at an American culture in which racism was still undisguised and racial segregation—legal, social, and economic—very much the norm. In 1953, soon after a road show version of the play completed a successful two-week run in Atlanta, two outraged Georgia state legislators denounced it as propaganda and vowed to introduce bills outlawing the showing of “movies, plays, musicals or other theatricals which have an underlying philosophy inspired by Moscow.” One of them pointed directly to the lyrics of “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught.” In his eyes it was an endorsement of interracial marriage, which, until the Supreme Court’s landmark Loving v. Virginia decision in 1967, was illegal in several southern states.

“To us that is very offensive,” he said. “Intermarriage produces half-breeds, and half-breeds are not conducive to the higher type of society…. In the South we have pure blood lines and we intend to keep it that way.” Asked to comment, Oscar Hammerstein replied that the legislators had it right: the song was indeed a protest against racial prejudice. “It’s no undercover propaganda,” he added. “If they don’t like it, that’s too bad.”

In the film (although not in Michener’s book), Joe and Emile undertake a dangerous coast-watching mission together. Joe is killed in action. Nellie’s anguished uncertainty about Emile’s fate leads her to the realization that love must conquer prejudice, and when he returns alive she marries him and forms a beautiful family with him and his children.

It would be nice to suppose that Americans have learned South Pacific’s central message in the decades since it hit the silver screen. Sadly, that is not the case. And so South Pacific continues to underscore, as theater critic Jim Lovensheimer noted in 2010, “the irony of Americans fighting a war against racist enemies while their own racism remains unresolved.”