It was a new kind of war.

In less than a decade the United States had sided with former enemies, retired its most famous general and settled with bitter foes—ex-allies—for nothing more than a stalemate. President Harry Truman called it a “police action.” The press called it the “Forgotten War.” Trying to make sense of it, in January 1952 a correspondent for Reader’s Digest and the Saturday Evening Post joined the Task Force 77 commander, Rear Admiral John “Black Jack” Perry, on his flagship, the aircraft carrier Valley Forge. James A. Michener was researching what would become the classic story, and arguably greatest film, about the Korean War: The Bridges at Toko-Ri.

“In those days of research for Toko-Ri I would participate in catapult takeoffs and cable-grabbing landings many times,” wrote Michener, a World War II naval officer who had won the Pulitzer Prize writing about combat on sultry tropical islands. In the wintry Sea of Japan, with victory nowhere in sight, he wanted to know, “Have Americans lost their moral courage?”

The “Happy Valley” was then on its third of four tours of Korea, and earning a darker nickname: “Death Valley.” Since early December 1951 its air group had lost eight aviators, starting with 25-year-old Harry Ettinger. On his first night-interdiction mission, Ettinger’s Douglas AD-4NL Skyraider was hit by anti-aircraft fire south of Wonsan. He and his crew of two bailed out. Almost two months later, on February 7, Army intelligence revealed that Ettinger had been spirited from captivity by anti-Communist North Korean partisans. They were packing him out on a stretcher toward Wonsan Harbor, and in need of helicopter pickup.

The rescue fell to Chief Petty Officer (Aviation Pilot) Duane Thorin on the heavy cruiser Rochester. One of the Navy’s first chopper jocks, Thorin had made more than 130 pickups from hostile territory with his little Sikorsky HO3S-1. He was skeptical of this mission, though, particularly when an Army intel operative insisted not only on coming along, but also loaded down his “Horse” with medicine and a radio for the partisans. “Weight is very critical in this machine, especially in this kind of operation,” Thorin warned. “…We could carry very little, no more than 150 pounds including his transceiver. And it was stressed that it must all be out of the helicopter before we brought the man [Ettinger] aboard.”

At 6 a.m. on the 8th, three F4U Corsairs and three Skyraiders took off from Valley Forge on a ResCAP: rescue combat air patrol. The frozen hillside pickup site appeared to be clear of enemy troops, but its terraced, stair-stepped rice paddies were too narrow for Thorin’s Sikorsky to set down. He planned to hover while the supplies were offloaded and the passenger put aboard, but when the Horse came down, the “stretcher-bound” Ettinger darted out from cover. Thorin shouted at the Army agent: “Dump that stuff out! Right now!”

Too late. Ettinger hurled himself aboard. Burdened with all three men plus the extra gear, the chopper grounded, one wheel off the terrace. It tipped, rolled and struck its rotor blades on the frozen ground.

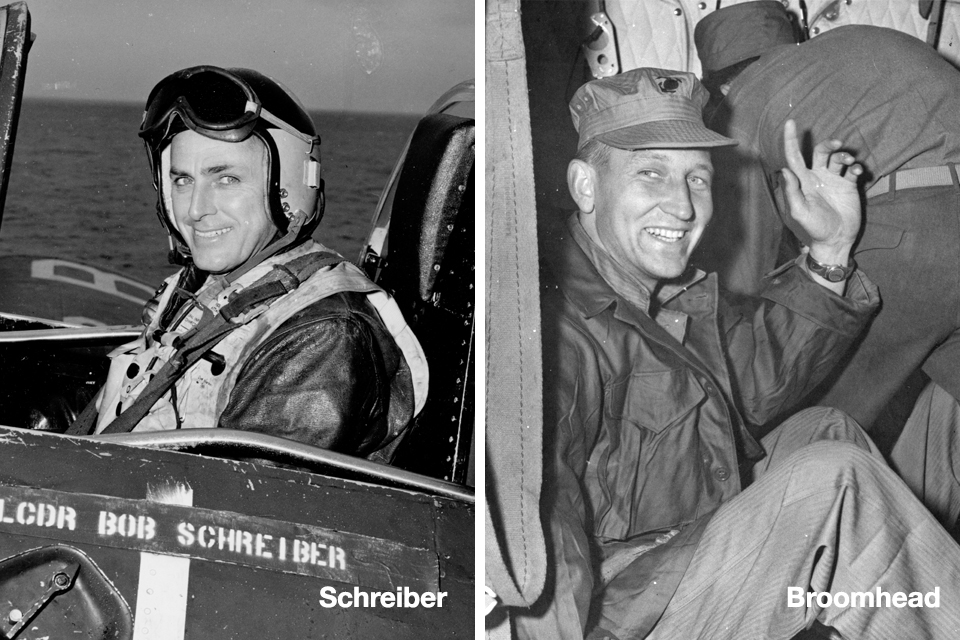

Out at sea Valley Forge prepared to launch the morning’s scheduled mission. At Samdong-ni, near the villages of Poko-ri and Toko-san (names Michener would later combine for his fictional Toko-ri), three bridges crossed the bottom of a deep, winding river valley. Lieutenant Commander Robert “Iron Pants” Schreiber of attack squadron VF-194 would lead the strike against them, but not in flashy new jet fighters. “The big prop-driven AD Skyraiders were the Navy’s only aircraft able to destroy the bridges,” conceded Grumman F9F Panther pilot Lieutenant Kenneth C. Kramer, noting they were capable of carrying “the big 2,000-lb. blockbuster bombs.”

Recon photos had revealed the valley of Samdong-ni was studded with Russian-made 37mm radar-controlled quad cannons. Panthers would speed ahead to take out the guns, and two Corsairs would try to keep any stray Korean heads down, but the bridges were up to the Skyraiders. “We had no illusions as to what we were in for,” remembered Schreiber’s wingman, Lt. j.g. Richard Kaufman. Lieutenant Bob Komoroff, who had been best man at Kaufman’s wedding, would lead the second section, with Ensign Marv Broomhead as last man through. “I was very uncomfortable,” recalled Kaufman, “knowing that the rescue helicopter from the Rochester was not available.”

At the helo wreck near Wonsan, the Americans had barely extricated themselves when North Korean troops emerged from cover and closed in. The ResCAP came down to strafe them with cannons. “The explosive rounds sounded like popping corn,” recalled Thorin of huddling against a bank as shrapnel “…sizzled through the trees above us, close enough that I felt the breeze.”

The enemy gave back just as hot. Five of the six ResCAP planes took hits. Lieutenant John McKenna’s F4U-5N lit up. He radioed that he was making for open water, but the flames spread to his cockpit. The Corsair struck the ocean, McKenna going MIA. Lieutenant Mel Schluter’s Skyraider was hit, though he managed to reach air base K-50, just over the border at Sokcho-ri. The others circled the crash site as long as they could, but finally, out of ammo and low on fuel, they had to make for K-18, Kangnung.

Meanwhile Schreiber’s half-dozen prop planes arrived over Samdong-ni. “We spread out in a loose tailgate racetrack pattern 12,000 feet above the bridges,” Kaufman recalled, “so as to attack out of the sun. We were to drop the three centerline and inboard 1,000-pound bombs on the first run, saving the 250-pounders carried on the wings if necessary.” Seeing little evidence of flak suppression, they guessed their jet escort had hurried on to the Thorin crash site. “The Panthers put the gun crews on alert,” Kaufman realized, “so when we arrived a half hour later, they were waiting for us.”

As Schreiber’s dark blue AD rolled into its bomb run, Kaufman saw the snowy white valley erupt: “All hell broke loose. In my 30 missions over North Korea thus far, it was the heaviest flak I had ever seen.” And it was his turn to head into it.

“I was diving about a thousand feet behind Schreiber,” he remembered. “I descended into the valley in a 60-degree dive, dive brakes extended to stabilize at 280 knots at the release point.” For 15 seconds each Skyraider ran a deadly gantlet, the likes of which movie audiences would only remotely experience. “We went in so low that the guns on the hilltops were shooting down at us,” Kaufman recalled. “I really didn’t have time to concern myself with the flak tracers and bursts all around me. Accelerating to 360 knots at full power, 1,000 feet and 4 g’s on the pullout was our plan to get through.”

Miraculously, it worked. The Skyraiders all came out of the valley of death untouched. Looking back from 6,000 feet, though, they saw that only two of the bridges were down. They would have to tempt fate again.

At Wonsan, Thorin remembered, “There were covering aircraft overhead throughout the day.” A flight of Corsairs from USS Philippine Sea was keeping watch when an HO3A-1 from a landing ship off the coast came to the rescue. “The ‘flop-flop’ sound of a helicopter roused all of us,” said Thorin, recognizing the aircraft and even the faces of its crew, but hearing “…some firing at the helicopter by the troops above the cutbank, and the distinctive ‘splat’ of one round striking it.” The chopper made two approaches, but was driven off to an emergency landing on the cruiser St. Paul.

Huddling beside Thorin, Ettinger said, “I’m sorry I got you guys into this mess.” Thorin blamed Army intel.

At Samdong-ni, Kaufman followed Schreiber down on their second bomb run with 20mm cannons blazing, trying to suppress some of the groundfire. He pickled his wing bombs and banked away, Komoroff right behind him. With four aircraft dropping dozens of 250-pounders on one bridge, the smoke and dust was so thick they couldn’t immediately discern the damage, but saw the odds had caught up to them. Broomhead’s AD was fleeing eastward down the valley, streaming smoke.

“I am hit,” Broomhead radioed. He had been grazed in the head by shrapnel or a small-caliber round. His Skyraider didn’t have the power to climb. “I’m losing rpms.”

“Bail out,” Schreiber told him.

“I’m already too low,” Broomhead said. “I have to find some place to set down.”

“We followed him about nine, ten miles,” recalled Kaufman. Broomhead spotted a snow-covered mountaintop clearing and brought the stricken Skyraider in. “The crash was sudden in a flurry of snow as he hit and skidded to a stop in about 300 feet. The engine broke off but there was no fire. All was quiet.” Broomhead had fractured his back and broken both ankles. He finally dragged himself from the cockpit. “As I buzzed over him on a go-around circle, I saw him lying by the wing in the snow,” Kaufman said. “He rolled over and waved to me.”

The two Corsairs were already low on fuel. While Kaufman and Komoroff orbited down low against the inevitable arrival of enemy troops, Schreiber went high to call a rescue chopper. With two already down, the nearest was 100 miles up the coast, off the light cruiser Manchester. Marine Corps pilot Lieutenant Edward Moore and 1st Lt. Kenneth Henry were artillery spotting for shore bombardment, Henry having volunteered just for a taste of combat. They hurried south.

The multiple shootdowns were sucking in aircraft like a Pacific typhoon. Aboard Valley Forge, Michener was listening to the radio chatter. “Word of the situation flashed through the fleet,” he would write. “…Pilots insisted on going in to get their men.”

Lieutenant Ray Edinger, executive officer of VF-653, took the assignment on his day off. “They gave me three Corsairs and one AD…to go out and relieve the Res-CAP” at the Thorin site. Partway there, they were alerted to Broomhead’s crash. Edinger diverted the Skyraider and a Corsair to it while he and his wingman relieved the Philippine Sea flight over Thorin. They spent two hours strafing with cannons and 5-inch HVAR (high-velocity air-launched rockets). One of Edinger’s hangfired, and his wingman took a hit. Just as a second flight of “Phil Sea” Corsairs arrived, Edinger heard a thump and was told he was streaming oil. “I looked out at the left wing, and sure enough, it’s all running out,” he recalled.

When Moore’s HO3S-1 wafted up to Broomhead’s mountaintop crash site, now surrounded by North Koreans, it ran into a barrage of groundfire. The Horse collapsed onto the snow and rolled on its side. Both crewmen got out—Henry hobbling with a sprained knee—and managed to reach Broomhead, who was now unconscious. The Americans circling overhead saw them drag him away from his wrecked Skyraider.

Things were getting worse at Thorin’s crash site, too. “Some time after noon a Marine helicopter came looking for us, moving upslope over the open area about 200 yards outside of our hideaway,” he said. “An HO4S, it had capability of taking all three of us.” The Sikorsky Chickasaw had a crew of two and could carry 10, but by now the downed Americans realized they were just bait in a trap. Thorin knew that “If we were to break out into the open area where this helicopter could pick us up, both it and ourselves would be a well-centered target for all of the troops in the vicinity. All things considered, it seemed best to let the Marine helicopter pass on by.” He and Ettinger stood up so every aviator and enemy soldier in sight could see them raise their hands.

Meanwhile Edinger, fleeing seaward at full throttle, realized his Corsair’s engine should be dead. His leak wasn’t oil, but hydraulic fluid. It meant putting down on Valley Forge with no flaps, no locked-down landing gear, maybe not so much as a tail hook, not to mention the hung rocket still on his wing. But having made it out over the water—and against the advice of the carrier crew, who all but ordered him to ditch or divert to K-18—Edinger was determined to come aboard, no matter what. “They wouldn’t let me land until…they put the [crash barrier] fences up and were going to put a line of donkeys [tow vehicles] there.”

His first approach—no flaps, straight in—was too fast, and Edinger got a wave-off. He wound the F4U back around the circuit and hung it in the air at near-stall speed, hose-nose so high he had to slide open the canopy and stick his head out to see the LSO give him the cutthroat signal to chop throttle. The Corsair smashed down on its bent wings. On impact the live HVAR tore loose, skittering across the deck until two anonymous, heroic deckhands tackled it and pitched it overboard. Edinger’s F4U was dragged below on its belly.

A bad day was coming to a bad end. “A stolid fury settled upon the U.S. fliers,” wrote Michener, “and with it an agonizing despair.” As darkness descended, the Siberian wind gusted toward 60 knots over North Korea. An Army chopper couldn’t quite reach Broomhead, Moore and Henry. “It had space for only two men, and Broomhead was unconscious,” Michener learned. “To try to carry him the 200 yards under enemy fire would be fatal. Moore and Henry might make it in a quick dash, but they would not leave Broomhead. They waved the helicopter away.”

Night fell. At first light aircraft hurried back to the crash sites, to find only the remains of the wrecks and blood on the snow. “We gave all those guys up for dead,” Kaufman said.

“Here was complete failure,” Michener declared in the July 1952 Readers Digest. “…Helicopter[s], planes and men were lost in the futile tragedy. The enemy had a field day and we had nothing. Nothing, that is, except another curious demonstration [that] sometimes defeat does actually mean more to democracy than victory.” When the chips were down, Michener assured Saturday Evening Post readers, “These pilots of Admiral Perry’s task force are as heroic as any men who have ever fought for the United States.”

And the defeat, it turned out, wasn’t total. Photorecon planes revealed all three bridges at Samdong-ni had been taken down. Ettinger, Thorin, Broomhead, Moore and Henry, even Ettinger’s Skyraider crew and Thorin’s Army intel passenger, all survived, and were among those repatriated in a prisoner exchange at war’s end.

“I cherish those experiences as among the most exciting I’ve ever had,” Michener would recall. “When the time came to write the novel…I strove to capture each violent action and its significance.” He would become famous for massive historical epics. His story of Korea, published in its entirety in one issue of Life magazine, was one of his shortest, though Michener always called it his “best single piece of writing.” For many Americans, The Bridges at Toko-Ri remains their only experience of the Forgotten War.

Frequent contributor Don Hollway thanks Richard Kaufman for his photos, video and recollections of his friend James Michener and flying the “Toko-ri” mission, as well as Christina Thorin for sharing photos and memories of her father. For further reading, Hollway recommends: Such Men as These, by David Sears; and, of course, Michener’s The Bridges at Toko-Ri, both the film and novel. For more info, photos and video, see donhollway.com/toko-ri.

The Real “Bridges at Toko-Ri” originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe today!