Before gaining political prominence, the retired United States Senator fought with the 10th Mountain Division during World War II.

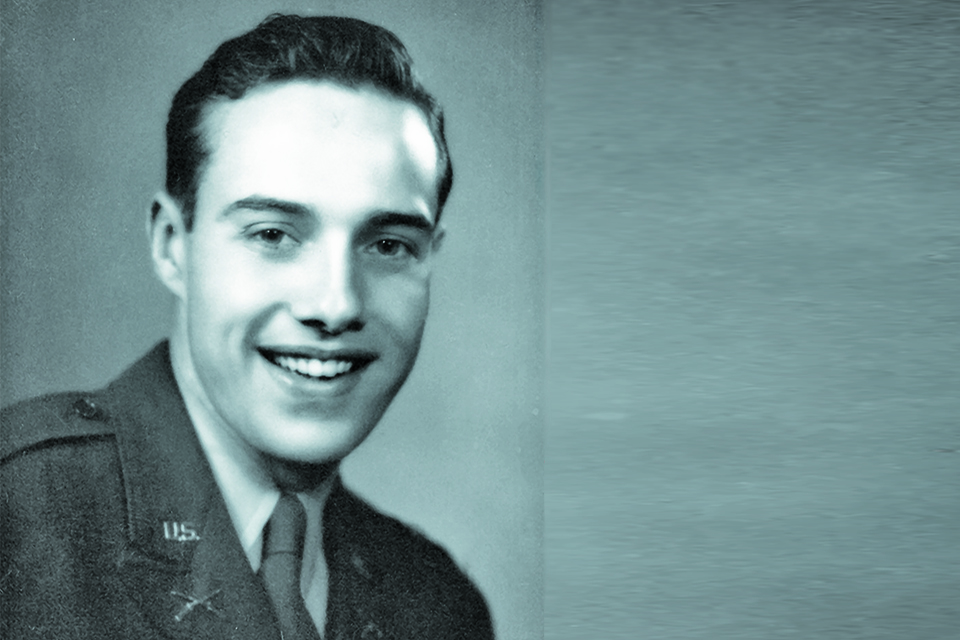

ROBERT J. DOLE rose to fame during a decades-long career in state and national politics that included 35 years in Congress, campaigns for the vice presidency and presidency, and roles as an advocate for veterans and Americans with disabilities—and as a pitchman for the drug Viagra. However, during World War II the amiable Kansan was a GI Everyman.

As Depression-era children, he and his siblings had many jobs; a teenaged Bob was a soda jerk at Dawson’s Pharmacy in his hometown of Russell, Kansas. While a student athlete at the University of Kansas from 1941 to 1944, he joined the Enlisted Reserve Corps—later renamed the Army Reserve. Inducted in 1943, he briefly participated in the Army Specialized Training Program before being reassigned to the infantry. There he qualified to train as an officer and was commissioned a second lieutenant.

On April 14, 1945, Dole’s unit of the 10th Mountain Division was in northern Italy, advancing under fire on a German position, when enemy machine-gun rounds ripped into his back, severely wounding him. More than once during an excruciating 39-month recuperation, recounted in his 2005 memoir, One Soldier’s Story, Dole’s survival was in doubt. However, he recovered, adjusted, and became a lawyer. At 92 he is of counsel to the law firm Alston & Bird in Washington, DC, where this interview took place.

How did your upbringing affect your time in the military and after?

Both my parents were hard workers, which they passed on to us. My dad was a working man who dealt with farmers all his life. My mother, Bina, sold sewing machines and taught sewing. There were four of us siblings and we were expected to study in school and work on Saturdays, either delivering handbills or newspapers or mowing lawns. We grew up knowing a little about responsibility.

Which job did you like most?

I loved being a soda jerk. I gained eight pounds my first month working at Dawson’s. My favorite treat is a chocolate shake. I like ’em real thick, where you have to eat ’em with a spoon, so I put in a lot of ice cream and chocolate syrup but not too much milk.

How did lettering in three sports at Kansas University serve you in the army?

Playing sports made me more competitive, which I think helped me not only in the army but all the way through life. When you’re in a race, you want to win, so you give it all the energy you have. As I think back on it, athletics was a big plus for me.

What surprised you most at first about military life?

Digging holes. If someone caught you smoking, you had to dig a big hole to bury the cigarette butt.

What memories do you have of the action that took you out of the war?

We were on a hill called 913. There were Germans in our way. My radioman, Corporal Sims, had been wounded—mortally, it turned out. I was trying to get Sims back to safety when I felt a sting on the right part of my back. After that I was pretty much out of it. The bullet bruised my spinal cord, which caused me trouble with my hand and leg.

That happened three weeks before the war in Europe ended. How did you cope with that?

At that age—I was 21—I thought I’d be healed up and be all right. You don’t think of what’s really gonna happen. I figured the surgeons would patch me up and I’d be okay, but when you’re in a hospital in Pistoia, Italy, you get to thinking a little more that your condition may last a while. That’s true particularly when other people have to write letters home for you—they were happy to do it, of course, but not being able even to write is pretty tough. Even with that, I never was, quote, “depressed.” I wasn’t happy but I was feeling fairly normal, although I couldn’t figure out why I couldn’t walk. I thought, I’m a young guy, I’m gonna be okay.

Tell us about Percy Jones Army Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan.

I was part of what we later called the Percy Jones Alumni Caucus. Our ward’s ranking officer was Colonel Philip Hart, who later became Senator Phil Hart, after whom the Hart Senate Office Building is named. Phil was recovering from an arm wound that was serious, but not as serious as some. He was able to run errands for all of us, and he really took care of guys like a former football player from Michigan State who, like me, was in a neck harness. Another guy in our ward was Dan Inouye. He was the best bridge player in the whole hospital and later represented Hawaii in the Senate. He had been wounded in Italy, too—he lost his right arm. I was skinny; I had gone into the army at 190, but I had lost 70 pounds. These days I’m trying to lose five, which is a lot harder than it was to lose 70 back then. But Dan only weighed 93 pounds. That was the core of our little alumni caucus.

What pulled you through?

When I was growing up my dad was always wisecracking, and I learned from him to have a good sense of humor. The nurses would wheel me around to visit patients who weren’t ambulatory; I remember Joe Brennan from Chicago, who had bedsores that would make you cry. I visited him a lot. Joe and I spent a great deal of time together, and he was always cheerful and positive.

There were a few noteworthy disincentives to speedy recovery.

We had great nurses, like Kathy Stobbins, who was tougher than nails; if we didn’t do what she said, we were in trouble. At the beginning I wasn’t able to feed myself, so at every meal one of the nurses would feed me. I probably could have taken care of doing that sooner but our nurses were so good-looking I saw no reason to hurry. Finally, though, I realized that if I wanted to get better I would have to start eating on my own, so I did the right thing.

What was the most difficult part about returning to Russell?

Initially I didn’t know whether I was going to have a career at all or wind up selling pencils on a street corner somewhere. I was deeply embarrassed about not being able to use my right arm, because I had no feeling in it, and about not being able to walk too well. I felt kind of useless. Fortunately, I had this drive and sense of purpose that I had acquired from my parents and which I never forgot. You gotta turn the page or you just vegetate.

When did things brighten up?

I had a really great experience in law school. As a Kansas University undergraduate before going into the army, I did not have what you would have called an illustrious academic career. The war was on, and everybody was going off to join the service, so we had to have a lot of parties and—jiminy—I sure missed a lot of lectures, although I didn’t miss many parties. I attended the university, but not many classes. Didn’t flunk out, but I had some Ds.

At law school, however, I was more focused. I had great professors and the Veterans Administration had furnished me with a disk machine I could use to record their lectures. Each night I would listen to the disks I had recorded that day and I would laboriously write down everything that was on them. As a result, I had the best notes of anybody in my class, and around test time I became a very popular guy with people who had been goofing off in class when it came to note-taking. I came through law school with all As except for a B in municipal law. I didn’t know anything about municipal law then, and I don’t know anything about municipal law now, but I vividly remember using that recorder.

You have a satisfying way of spending part of your weekends.

For a number of years now I’ve been going over to the National World War II Memorial every Saturday. I go there to meet the veterans—guys from my generation, but also from Korea and Vietnam. These fellows usually come to the World War II memorial first, and then make their way down the Mall to the Korean War Veterans Memorial and the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. This Saturday there’s an Honor Flight group coming in from Orlando, Florida. I’m looking forward to seeing those fellows. ✯

Originally published in the November/December 2015 issue of World War II magazine.