By October 1951, the seesaw ground war in Korea had stalemated across the 38th Parallel, but in the air the kill ratio of F-86 Sabres over MiG-15s—famously claimed as 10-to-1 by war’s end—was running more like 2-to-1 against. Seventy-five Sabres of the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing were all that stood between more than 500 MiGs and complete air superiority. Then Major George A. Davis Jr. took over the wing’s 334th Fighter Interceptor Squadron. He would soon make fighter pilot history.

“Davis is a very mild-appearing guy,” noted a fellow Sabre flier, “but when he straps on a fighter he’s all tiger—a hell of a sharp pilot and gunner, and he must have the eyes of an eagle.” In November “One Burst Davis” scored a MiG probable and two confirmed. And on the 30th, 10,000 feet above the mouth of the Yalu River—the border with Red China—he spotted nine Tupolev Tu-2 “Bat” bombers on a raid. Jets versus props: the kind of fight Americans had rarely enjoyed since MiGs took to the air. In three passes Davis got three kills. But with the American formation scattered and on bingo fuel—just enough to get home—Captain Raymond O. Barton, who was getting shot up by a pair Chinese MiG-15s, called for help.

“I don’t have enough fuel either,” Davis answered, “but I’m on the way.” Too far off to tell the sweptwing fighters apart, he radioed Barton to jink left-right, then homed in on whoever didn’t follow orders and shot the enemy leader down into Korea Bay. The wingman broke off. Davis landed at Kimpo on his last five gallons of gas. He was the fifth American ace of the Korean War, but much more than that. With seven victories against the Japanese in World War II, he was a double ace. And an ace in two wars. And an ace in both piston and jet fighters.

Of more than 1,400 American aces from all wars, only six others have pulled off such a hat trick. Not all could make the leap from props to jets, or even from first-generation jets to the Sabre. Five-victory WWII ace Colonel Harrison Thyng, the 4th FIW commander who scored his first MiG that November, admitted: “The F-86 is a highly specialized jet aircraft. It cannot be handled and flown like a typical Air Force fighter plane, or even like the F-80 and F-84 jet.” When the Pentagon converted a second wing, the 51st, to Sabres, Thyng’s deputy, Colonel Francis Gabreski—the top American ace over Europe, with 28 victories—took command, with fellow ETO ace Major William T. Whisner (15½ victories) as squadron leader. By the start of 1952, they had scored three MiGs each.

Meanwhile Davis, with two kills on December 5, claimed two more on the morning of the 13th, to become a triple ace—America’s first double ace over Korea—and on his afternoon mission gunned down a pair of Chinese MiGs in less than a minute. “Four in two missions—gadzooks! He gets them by the bag full,” wrote an admiring 4th Wing pilot. “They say two of them just bailed out in fright as soon as he got hits on them.”

On January 11, 1952, Gabreski got one, west of Pyongyang. “Flames belched from the MiG’s tailpipe, then part of his tail broke off,” he later wrote. “The plane went down in an uncontrolled spin.” But that same day Whisner reported: “I sighted two MiG-15s and attacked the number two MiG. After firing several short bursts I observed strikes in the tail section, wings and fuselage. The pilot bailed out and the plane crashed….” They were still tied, four each.

And that month Davis scored zero. The Air Force held him to one mission a day. “They’re trying to make a hero of me,” he wrote of the media attention focused on him, “and I find it rather embarrassing.” Davis may have been publicity shy, but by all accounts he had acute “MiG madness,” the affliction peculiar to F-86 jockeys that compelled them to go against training, orders and odds to score Korea kills. On February 10, he and his wingman dived on a dozen MiGs north of Pyongyang—six to one. Davis got two, bringing his score to 21, but according to his subsequent Medal of Honor citation, “rather than maintain his superior speed and evade the enemy fire being concentrated on him, he elected to reduce his speed and sought out still a third MiG-15.” As he fixated on his target, another MiG fixed on him. With cannon hits all over its fuselage—one right behind the cockpit—his Sabre crashed into a mountainside about 30 miles south of the Yalu. Davis was awarded the Medal of Honor and promoted to lieutenant colonel, posthumously.

MiG madness may simply have been symptomatic of WWII aces reliving their glory days, pursuing Axis fighters right to their roosts. Thyng’s wingman claimed he was sent down to “boom” the Communist air base at Antung, Manchuria, at minimum altitude and maximum speed, just to flush some game. When a MiG took off, Thyng came down to blow it all over the airfield, and the Sabres “blasted back across Antung, throttles wide open, dodging the flak.” Gabreski is said to have downed a MiG and victory-rolled right over the Antung runway. Such missions in the no-go zone beyond the Yalu were often left off the books, with kill credits unclaimed or denied and gun-camera evidence burned, unless Sabre pilots were in hot pursuit of MiGs.

Ten days after Davis went down, Gabreski so nearly flew up his target’s tail—“I had learned in World War II, the best way to bring one down was to pull in close behind before firing”—that flying debris cracked his windscreen. The MiG got away, smoking. Whisner urged Gabreski to finish it off before it reached the Yalu. “I thought better of crossing into Red China under those conditions, and broke off the attack,” Gabreski recalled. “Bill, however, stayed behind the MiG and followed him across the river.” “Whiz” credited Gabreski with the victory, but admitted to personally administering the coup de grâce some 50 miles beyond the border. Each argued the other should get full credit—and ace status—but finally agreed to split the difference: 4½ kills apiece.

Three days later, as Whisner opened up on a MiG over Sinuiju, a second dropped in on his tail. All three jets went on a wild chase. The trailing MiG couldn’t get a shot, but Whiz did. His victim ejected just before his plane exploded. With 5½ victories Whisner became the 14th ace in Korea, and the first WWII ace to follow Davis into the history books. He would remain the only Air Force pilot who was both an ace in two wars and a three-time winner of the Distinguished Service Cross.

In April, near the end of his 100-mission tour, Gabreski dived out of the sun onto a MiG’s tail. “I pulled my nose through his turn, fired a burst, and watched as my API [armor piercing incendiaries] lit up his tail pipe…,” he said. “That was enough for the MiG driver. He leveled out briefly, blew off his canopy, and punched out.” One last score, two weeks later, was the icing on the cake. Gabby’s 6½ victories—34½ total—made him America’s surviving ace of aces, an honor he held to his death in 2002.

A month later Thyng scored his fifth, without firing a shot. He and his wingman turned into attacking MiGs that broke upward so hard one of them actually broke. (In tight, high-speed turns, the MiG-15’s lack of hydraulic controls and weak tail structure sometimes led to catastrophic failure.) Smoking, it pitched over into a dive and never pulled out. With five kills in each of his wars, Thyng had made his mark. Crediting later victories to wingmen, he would retire as a brigadier general.

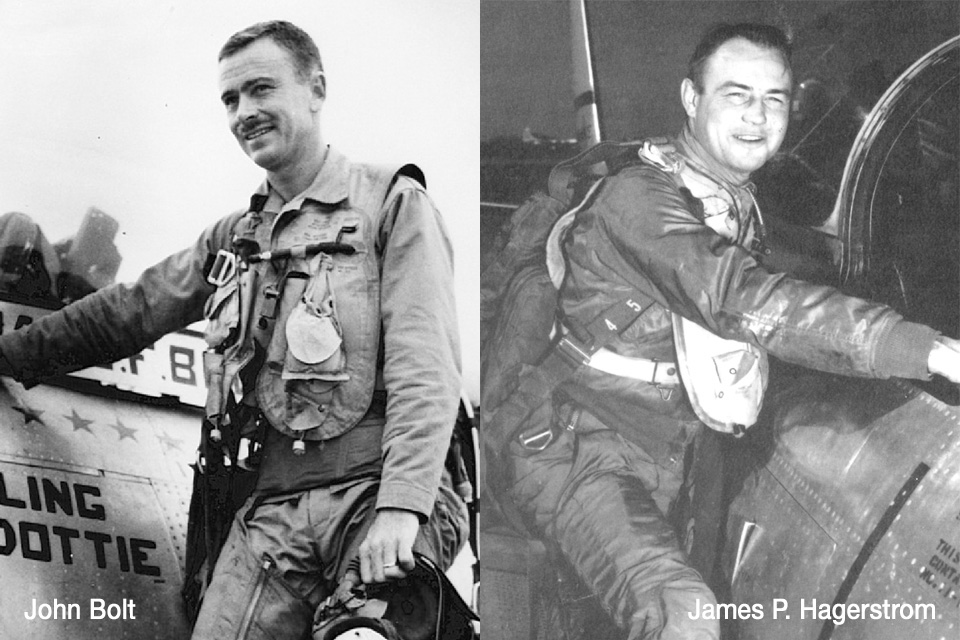

By August Whisner was teaching gunnery at Nellis AFB, in Nevada. One of his students, five-victory ace Major James P. Hagerstrom, considered flying Sabres with the 4th “the assignment I had spent my life preparing for.” He blew up his first enemy fighter, on November 21, at such close range that he came back to Kimpo with a piece of it in his wing. On Christmas Day he followed a MiG right up to 50,000 feet—the Sabre’s extreme ceiling, but also the MiG’s. It fell into a vertical dive, and its pilot ejected.

In November another Nellis gunnery instructor joined the 4th: Major Vermont Garrison, the “Kentucky Marksman,” who had downed more than seven German aircraft in WWII. He scored his first Korean kill on February 21, 1953, and as 335th FIS commander was one of the few pilots to fly Sabres armed with four 20mm cannons. These could carry just 100 rounds for each gun, good only for about five seconds of firing. Diving on six MiGs over the Yalu’s Suiho Reservoir on March 26, Garrison needed just one burst to cripple his target and another to send it down. He was one of only four pilots to score a confirmed kill in a cannon-equipped Sabre.

Meanwhile Hagerstrom, transferred to the newly Sabre-equipped 18th Fighter Bomber Wing, wasn’t going to let ground-pounding missions keep him from downing MiGs. In February he had chased one through the smokestacks of Mukden, China, 100 miles inside Manchuria, before its pilot ejected. He once boomed Antung at Mach .9, just 15 feet off the ground, and in March ran out of bullets shooting up a MiG over the base, leaving his wingman to finish it off and himself a half-kill shy of ace. On the 27th he told his fellow pilots: “I’ve got to do this thing. I’m gonna do it, and if you don’t want to go with me, that’s fine, I’ll understand. We are going to go up there and give it one good try south of the Yalu, and if we don’t scare anything up, I’m going after them today.”

Hagerstrom’s flight intercepted six MiGs over Antung. He ran one down to 15,000 feet, then back up past 30,000. “Every time my pipper was in his tail pipe, I’d give him a burst and another burst and another burst,” he said. “I ended up coming up canopy to canopy with him.” Both planes ran out of airspeed at 36,000 feet. “Sitting there…right above his air base….he leaned his head back and blew the seat out. So I thought, ‘I wonder what he’s going to tell those guys at the officers club tonight….’ Seeing a burning MiG crash on your own base can cause a hell of a morale problem.”

Hagerstrom scored two more victories by May 16, the last day of his tour. He was sitting in the ops room awaiting a flight out when a call came in for an intercept mission. He picked three pilots on the spot and, still in uniform, led them north. His Sabres broke up a formation of 24 MiGs, and Hagerstrom got one last kill, bring his Korean score to 8½. He was the 18th FBW’s only ace.

Meanwhile Marine Corps Major John Bolt—a six-victory ace in VMF-214, the Pacific War’s famous “Black Sheep Squadron”—wangled an exchange posting to the 51st, flying wing for the eventual top-scoring American over Korea, Captain Joe McConnell. Bolt “was cut from the same cloth as McConnell,” said a fellow 51st pilot, “with his aggressiveness, sharp shooting and good eyes.”

When McConnell rotated home, Bolt took over as flight leader, declaring, “The next MiG I see is a dead MiG.” On May 16, the day of Hagerstrom’s last kill, Bolt and his wingman singled one out, even though two more were after them. The lead MiG tried to outclimb the Sabres—usually good for a getaway—but by the time the five fighters passed 45,000 feet Bolt estimated he had fired “500 rounds into that guy” and the pilot punched out.

Garrison still had only three kills. With peace talks nearly concluded, on June 5 he led four Sabres into Chinese airspace. “We were well north of the Yalu, which was a no-no, but we did it on a fairly regular basis,” admitted his “tail-end Charlie,” 2nd Lt. William Schrimsher. “Cruising at 40,000+ feet, Major Garrison saw sun flashes down low, so we did a ‘split-S’ and headed down to the deck. What he had seen were several MiG-15s taking off from Antung.”

They pulled in just 500 feet behind the still-climbing MiGs. “Our overtake speed was pretty high—I think we may have popped our speed brakes,” recalled Schrimsher. “Garrison shot down two of them in quick succession.” The trailing MiG exploded right in the flight leader’s path. Garrison flew through the blast to blow up another—his fifth—but, running low on ammo, sidestepped to let his wingmen score as well. “To my knowledge, it was the only time in the Korean War that all four pilots from a single flight were credited with at least a single kill apiece,” said Schrimsher, whose MiG is thought to have been the 700th downed in the war. He called Garrison “one of the war’s most aggressive Sabre pilots, and also one of the best.”

Bolt scored three victories that month, but early-July rain grounded both sides. “We hadn’t seen anything of the MiGs in over ten days—when all of a sudden I spotted four of them taking off from an air base on the other side of the Yalu,” Bolt recalled. “I nosed over and hit them just as they began to gain altitude.” He sent one enemy plane smoking into the ground and pulled behind a second. “I closed to within 500 feet and started firing up his tailpipe. I watched the pilot eject himself and the action was over. It took about five minutes for the whole show.” Though he scored in an Air Force unit, Bolt was all Marine; to this day his six kills over Korea make him the Corps’ only jet ace.

On July 19, now–Lt. Col. Garrison sent a MiG flaming down into a field for his 17th victory overall. Eight days later the cease-fire was declared.

In the more than six decades since, no other American aces have joined these seven. What made them special? Surely luck—being in the right place at the right time, namely two air wars just six years apart—played a role, but when luck ran out, skill and experience took over. MiG madness had nothing to do with it.

As RAF Wing Commander (and 34-victory WWII ace) James E. “Johnny” Johnson put it: “In Korea, unlike previous wars, colonels in their twenties were no longer the vogue. Complicated weapons systems like the Sabre were best flown by experienced flyers, and experienced flyers were best led by the veterans of the Second [World] War, many of whom added to their tally of German and Japanese victories….Grey-haired, well-decorated…they were impressive not for their youth but their age….[and] their motto— not the boldest but the oldest!”

Don Hollway wrote about John Bolt in his feature on the Black Sheep Squadron in our January 2014 issue. For additional reading, he recommends: The Inner Seven, by William E. Oliver and Dwight L. Lorenz; and MiG Alley: Sabres vs. MiGs Over Korea, by Warren Thompson and David McLaren. To view more photos, art and video, see donhollway.com/magnificentseven.

The Magnificent Seven appeared in the November 2014 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe here!