In 1945, the newly fielded U.S. 10th Mountain Division battled the enemy and the elements in Italy’s Northern Apennines.

ON A WINTRY DAY in Italy in the final months of the war against Nazi Germany, Major General George Price Hays, commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division, spoke to men from the division’s 85th Regiment. It was February 16, 1945. In three days, the soldiers of the 85th and the division’s two other regiments were slated to attack Germans holding the high ground of 3,800-foot Mount Belvedere and adjacent peaks in Italy’s Northern Apennines.

General Hays, then 52, had taken command of the 10th the previous autumn. As a young artillery officer in the previous war against Germany, he had been awarded a Medal of Honor. Weather-beaten and plainspoken, Hays reminded one of the soldiers gathered before him that day of a tough old cowhand.

The men of the 10th were eager to join the fight against the Nazis. Unlike their commander, though, they were not seasoned soldiers; their division was the next-to-last the U.S. Army would send to fight in Europe.

Their first weeks on the Italian front had been uneventful. Now, standing before the regiment as they gathered outdoors in the cold mountain air, Hays went over plans for the coming offensive, pointing out enemy positions on a large map. Mount Belvedere is the first in a line of peaks, all about 3,000 feet high, stretching northeast from the hillside village of Querciola and arrayed along a three-and-a-quarter-mile ridgeline. The most prominent of these peaks is Belvedere itself, along with Mount Gorgolesco and Mount della Torraccia. The three mountains overlook Highway 64, one of the few roads then cutting through the Apennines, connecting the region around Florence to the south—which had been held by the Allies since the previous fall—to Bologna in the north, in the northern third of Italy still controlled by the Germans.

The 10th’s plan of attack was complex and multipronged, with elements from the 85th, 86th, and 87th regiments involved in the initial assault from several sides of Belvedere and Gorgolesco. Once they had secured the summits of those peaks, the 85th’s 2nd Battalion, held in reserve, would push on to della Torraccia.

Capturing these three peaks was essential to the success of the Allied offensive in Italy in the fighting to come in the spring. The Allies would not be able to advance into northern Italy without clearing the Germans from the adjoining high ground. Twice before, other Allied divisions had attempted to overrun the enemy’s positions on Belvedere and failed. Now it was the 10th’s turn. Hays stressed the need for speed and audacity:

You must continue to move forward. Never stop. If your buddy is wounded, don’t stop to help him. Continue to move forward, always forward, always forward.

Dan L. Kennerly, a 22-year-old private serving in the 85th’s D Company, recorded Hays’s words in his diary. Before volunteering for the 10th, Kennerly had played football for the University of Georgia. Now he was moved to comment, “The General would make a hell of a football coach.”

The pep talk helped. From that point, the regiment’s motto would be “Always Forward,” or Sempre Avanti in Italian. What also helped was the specialized training the men of the 10th had undergone back in the States, learning how to fight on mountainous terrain and in cold weather. Their related identity as “ski troops” (as they were commonly called) or “mountain troopers” bred and reflected a strong sense of unit cohesion. That too proved essential to their subsequent combat record—which truly was one of going “always forward.”

THE STORY OF the 10th Mountain Division began five years earlier, in the late winter of 1940, when prominent American skiers and mountaineers began to warn military authorities of the potential threat German alpine troops posed should the United States become involved in the European war that had broken out the previous fall. Geography dictated that European armies needed to take alpine fighting seriously since so many national borders ran along the crest of mountains. The U.S. Army, in contrast, had no alpine troops and had never fought a battle on a snowy mountain. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall listened to the civilians, and by late November 1941 the first ski troops were beginning to gather at Fort Lewis in Washington State, to soon train on the slopes of nearby Mount Rainier.

By the end of 1942, the ski troops, now expanded to two regiments, had their own newly constructed training camp, Camp Hale, high in the Colorado Rockies. With the organization of a third regiment, they gained divisional status in July 1943. Initially known as the 10th Light Division (Pack Alpine), the unit acquired the simpler designation of 10th Mountain Division in November 1944, when they were temporarily based at Camp Swift in east Texas.

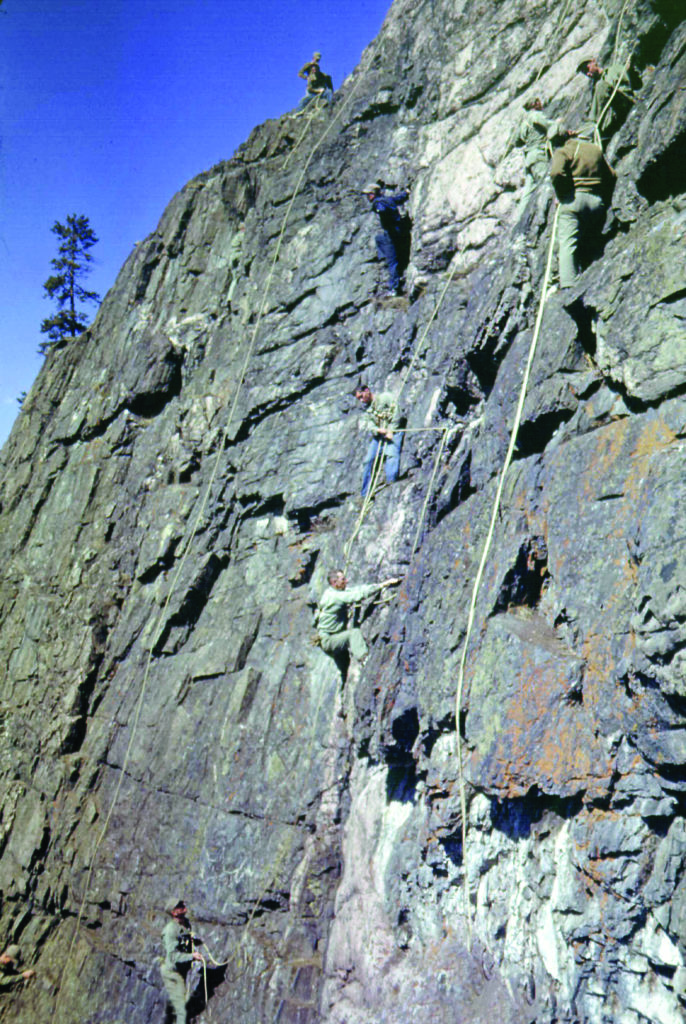

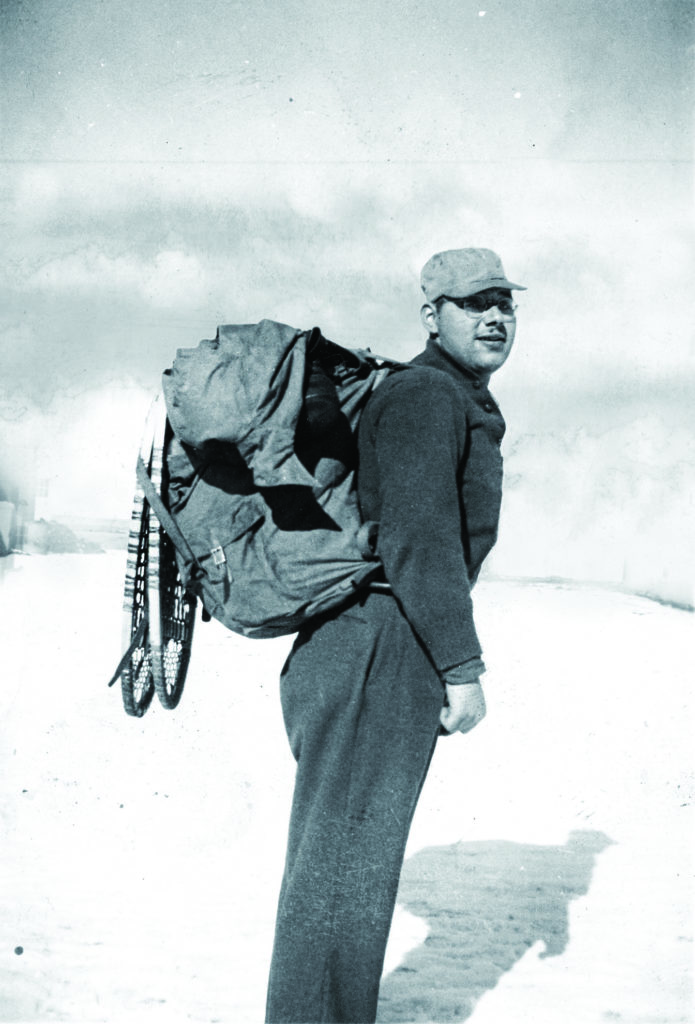

Their training had been uniquely rigorous, conducted in their Colorado days at altitudes between 9,000 and 14,000 feet, often in deep snow and blizzard conditions, sometimes without returning to the warmth of their barracks for weeks at a time. Some of the best skiers in the world, including refugees from Norway, Austria, and Germany, taught the recruits to ski in all kinds of conditions while carrying weapons and heavy packs. When the snow melted, the soldiers honed their rock-climbing skills. In the end, when the men of the 10th finally shipped out to Italy in December 1944 and January 1945, they left the skis behind and, once on the front lines, conducted only a few skiing patrols in the Northern Apennines, with scrounged equipment. But all the specialized training was not for nothing. They reached Italy fit and proud.

Lieutenant General Lucien K. Truscott, commander of the U.S. Fifth Army in Italy, ordered General Hays to deploy the 10th Mountain Division in the valley and hilltop villages below Mount Belvedere and to begin planning an attack—to be known as Operation Encore—for late February 1945. From his headquarters close to the front line, Hays studied the terrain, aerial photographs, and maps. He quickly noticed a crucial but heretofore ignored landscape feature. To the west of Belvedere, across a valley, lay a somewhat higher and—on the side facing the Americans—much steeper three-and-a-half-mile-long ridgeline. It became known as Riva Ridge, for one of the peaks along the ridgeline, 4,672-foot Monte Riva. From the Dardagna River that flowed along the side of the ridgeline, the climb up the east face to its summit was roughly 2,000 feet of elevation gain.

Although Mount Belvedere remained the main objective, the general knew he had to do something about the enemy soldiers who held Riva Ridge. From the ridgeline, the Germans had a clear view of the approaches to and summit of Mount Belvedere, which would allow them to call in accurate artillery fire on any attackers. But to take the ridge, his men would need to scale those cliffs. The German defenders had considered that so unlikely they didn’t bother to keep that side of the ridgeline under regular observation.

In January and early February, rock climbers from the 86th Regiment explored Riva Ridge’s eastern side and found five routes to the top; the overconfident Germans never noticed the activity. General Hays drew up the final plans for Operation Encore. After darkness fell on Sunday night, February 18, the men from units of the 86th would set off up four of the five trails to the summit of Riva Ridge. The remainder of the 86th, along with the men of the 85th and of the 87th—some 12,000 men all said—would depart shortly before midnight the next night, February 19, to seize Mount Belvedere and its adjacent peaks.

The attack on Riva Ridge proceeded flawlessly; the Americans took the Germans totally by surprise. By dawn of the 19th they controlled the ridgeline, at the cost of only a single man wounded. German counterattacks that began later in the day and continued for five days proved more costly but ultimately futile.

A mile or two to the east, men from the other regiments could hear the sound of firing on Riva Ridge. By sunset on February 19, they were cheered by the news that the ridge had been captured. It meant there would be no German artillery observers along the ridge to call in shells on them as they advanced toward their objectives that night and in the days to come. What’s more, the 10th’s attack on Belvedere would now be supported by .50 caliber machine guns and two 75mm pack howitzers laboriously hauled up to the top of the ridge after its capture.

The Germans on the Belvedere massif could also hear the firing going on to their west and must have understood that their positions were likely to be the next American target. Stealth and surprise had contributed significantly to the capture of Riva Ridge; the attack on Belvedere would enjoy neither.

HUGH W. EVANS, a sergeant in C Company of the 85th, published one of the first accounts of the battle for Mount Belvedere by a participant. He stressed the importance of the 10th’s mountain training:

Our attack was to begin a couple of hours before dawn. In other words, we were to carry out a night attack on a division scale, which means superb organization and timing on the part of the higher-ups. A night attack also requires trained troops because men must not fire their rifles, must keep quiet, and need skill in keeping contact. We had been keyed to this high pitch in all our training. We were ready.

At 11 p.m. on the 19th, the order was given for the mountain troopers to fix bayonets and move out. Staff Sergeant Marlin Wineberg was a mortar squad leader in D Company—the heavy weapons company—of the 85th. Everything at first went precisely according to plan, he recalled, with no confusion. To minimize the possibility of an accidental or premature discharge of gunfire alerting the enemy to their presence, or resulting in friendly fire deaths, the men assaulting Belvedere carried unloaded weapons. If they ran into opposition, they could use grenades or bayonets, but no one was allowed to load and fire before daybreak. The regiment walked uphill in two long single files. The weather was cold and clear, and a half-moon was rising in the sky. Despite the chilly February air, the men were soon sweating from exertion, especially the seven-man mortar crews in D Company laden with their 81mm mortars and ammunition.

As the men made their way up the lower slope, there were at first no sounds to be heard but the creaking of gear and an occasional muttered curse. Then the explosion of a German grenade abruptly dispelled the silence. The night filled with the chatter of small arms fire and the roar of explosives, as Wineberg recalled:

The enemy’s artillery and mortars are searching out the draws. They haven’t touched the one we are in as yet. One man keeps saying, “Stay here long enough and they’ll get us”; another man shuts him up. The General’s words come back, “When in artillery and mortar fire, drive ahead!”

They drove ahead, remembering General Hays’s injunction, “always forward,” while leaving a trail of dead and wounded comrades. One after another, the columns making their way around and up Belvedere and Gorgolesco crashed into German machine-gun, mortar, rocket, and artillery fire. They made their way through minefields, where a misstep could mean death or mutilation.

Among those tripping a wire to a stake mine that night on Gorgolesco was Captain Charles Page Smith, commander of the 85th’s C Company. The explosion broke both his legs but inflicted no permanent damage. He lay unconscious for some time on the battlefield. When he awoke, despite what must have been shocking pain, he also felt a kind of guilty relief. “The war was over for me,” he later recalled, “and I had survived.”

The fiercest fighting on the first day of the assault took place just below the summits of Belvedere and Gorgolesco, the former the objective of the 85th’s 3rd Battalion. By dawn on February 20, the battalion reached Belvedere’s summit. Over on Gorgolesco, the fighting was more prolonged. C Company of 1st Battalion was in the forefront of the assault there, where the fighting began around 3 a.m. Second Lieutenant Herbert Wright was C Company’s executive officer and remembered taking shelter in a wooded slope below Gorgolesco when the Germans discovered their location. Then “all hell broke loose,” as “artillery, mortars, ‘screaming meemies’ [rockets], and machine-gun fire enveloped us.” With Captain Smith incapacitated and unconscious, Wright took over as company commander, “a responsibility I really didn’t want.”

C Company stayed in the lead, fighting its way uphill. Around 7 a.m. Sergeant Evans and his squad, mixed with men from other platoons, found themselves just downhill of the final German stronghold on Gorgolesco’s summit. In the early morning light, Evans spotted his platoon sergeant and close friend, Technical Sergeant Robert Fischer, lying on the ground, next to another soldier who was holding his hand, trying to comfort him. Fischer was badly wounded, with a bullet through his lungs, and kept repeating, “Oh God. Please, not now.”

Evans attempted to stop the flow of blood from his friend’s chest wound with a piece of cloth torn from his jacket. But Fischer died within minutes. “Bob was 20,” Evans recalled. “I got up and left, my eyes filled with tears of anger. He was the first person I had seen die.”

A vengeful Evans jumped to his feet and, heedless of danger, raced uphill toward the German machine guns, calling for men to follow him. Amazingly, for a few crucial seconds, there was no fire from above. Near the summit fortifications, Evans and two men with him hurled grenades into the trenches there, then jumped into them, landing on the backs of dead Germans. “For the next ten minutes, I just kept moving,” Evans recalled, “throwing grenades and firing my machine pistol. The last German who got up and yelled ‘Kamerad!’ I held with an empty gun. The toll in Germans was about eight dead and twenty captured. Our objective was taken.” C Company lost seven men killed and 23 wounded in taking Gorgolesco; Sergeant Evans received a Silver Star for his actions that day.

THE GERMANS on Belvedere and Gorgolesco were veteran soldiers. They had been on the defensive for over a year but still held onto faith in ultimate victory. The fighting in February broke their spirit. A German officer’s diary, acquired by U.S. Army intelligence, revealed a new level of despair spreading through the enemy ranks. In an entry written at the time, the officer reported that “the 1044 [Infantry] Regiment is almost completely destroyed.” Two whole companies from the regiment had “gone over to the enemy” as prisoners. “This war is terrible,” he concluded. “Whoever has not gone through it as a frontline infantryman cannot possibly picture it.”

Allied control of the skies contributed to declining German morale. Throughout the daylight hours, American P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers and British Spitfire fighters buzzed overhead, bombing, rocketing, or napalming any German soldiers or guns they spotted. “The air corps finally arrives late,” Private Dan Kennerly, the Georgia football player, recorded with a touch of acerbic interservice rivalry in a diary entry for February 20: “probably had a second cup of coffee with their ham and eggs. Nevertheless, I’m glad to see them.” Spotters on Riva Ridge called in barrages from field artillery on German counterattackers. And, as engineers cleared paths for them through the heavily mined hillsides, Sherman tanks rolled into position to support the mountain infantry. Territory won with grenades and bayonets by the mountain troopers was now being consolidated with the full material advantages of the Allied side.

Even while fighting continued, the grim task of retrieving the dead was beginning. Crossing the saddle connecting Mount Belvedere and Mount Gorgolesco on February 21, Private Kennerly came across the mangled corpses of men from the 85th’s B Company lying where they had fallen in the assault on Gorgolesco the previous day. As he wrote in his diary:

They are lying everywhere, “frozen” in many different positions, instant rigor mortis. Some have their arms or legs sticking straight up, nothing is supporting them…. Near the low point of the crest are eleven bodies in a row…. One has the top of his head shot off, his brains have spilled out onto the ground. Glancing into the cavity, I recognize the stump of the spinal cord. It reminds me of a watermelon with all the meat gone. This is the most horrible sight I’ve ever seen.

The summits of Belvedere and Gorgolesco remained vulnerable to German counterattacks. Corporal Marty Daneman, HQ Company, 2nd Battalion of the 85th, found himself in the thick of the fighting on the second night on Belvedere; it was more than two weeks before he could bring himself to write about the experience in a letter to his fiancée Lois, back in Chicago. “I’ve been keeping something from [you], and I think that I’d better tell you…,” he wrote on March 9. “I think you must have read in the papers about the attack on Mt. Belvedere…. I was in on it darling — & the story I’ll tell you about it isn’t pretty….” Shortly after midnight on February 21, he recounted, he and his commanding officer headed up the slope of Belvedere to find their battalion’s advanced command post. Soon after the two men arrived, the Germans launched a counterattack:

I managed to get in a dugout during part of the shelling, but when the Krauts started to assault us, I got in a shallow slit trench & started firing. I spotted one Kraut running across a gully I was covering & shot him. I’d always wondered how I’d feel shooting a man & I found out quick enough. I felt no remorse doing it, almost pleasure. In one short period of time I learned to hate as I never thought I could.

With the capture of Mounts Belvedere and Gorgolesco on February 19-20 and their successful defense against counterattack, the first phase of Operation Encore was achieved. But the most difficult and prolonged phase of the battle was just beginning, as the 85th’s 2nd Battalion moved through the advanced American lines below Gorgolesco to the final objective, Mount della Torraccia.

En route, the battalion began taking casualties from mines. By 9 p.m. of the 20th, they were dug in on a forested ridge short of the summit. Private Robert B. Ellis was part of a machine gun squad in F Company. He left a tersely dramatic narrative in his war diary of the night and days that followed:

Dug in on crest of ridge with [Turman] Oldman. Scared to death. Cold… 3 of us left in my squad. 9 in platoon of 32 men. Horrible slaughter. Moved over ridge in morning and 1st [platoon] captured 3 Huns. MG’s popping all around… [Harlon] Jensen killed 10 yds. from me. Dug in fast. 88’s pounded us terribly. Slept that night and captured 14 Germans by yelling at them and firing machine gun. Killed my first Jerry on the ridge (Division objective). Moved the gun up to a new position and 1 minute later a mortar hit my old foxhole and wounded [Laverne] Staebell and [Leonard] Giddix…Counterattack surrounded us. Prayed in my foxhole and read my Bible.

Five German counterattacks and constant shelling decimated the battalion’s ranks. By the evening of February 22, the 2nd Battalion was reduced to some 400 men—roughly half its normal strength. Its soldiers displayed no shortage of heroism in the battle for della Torraccia: five were awarded Silver Stars for their actions, one posthumously. But they couldn’t take the summit; on the night of February 23-24, the 86th’s 3rd Battalion, under the command of Major John Hay Jr., 28—a former National Park ranger from Montana—relieved them. Hay’s battalion would go into action as soon as the sun rose.

The starting point for the day’s attack was 400 yards from the summit. At 6:50 a.m. artillery from the valley below began bombarding the German position. Ten minutes later, 3rd Battalion’s I and K Companies moved forward, taking casualties from machine-gun and artillery fire, but still seizing the summit shortly before 9 a.m. in hand-to-hand fighting. German counterattacks started late on the afternoon on February 24 and continued through the night. Around 1 a.m. on the 25th, a concerned officer back at the regimental command post telephoned Major Hay to ask if his battalion needed reinforcements. “Hell no, we don’t need any help here,” Hay replied. “We’re doing all right.” At dawn, the counterattacks ceased and the survivors of one German company, 40 men including their captain, surrendered. Mount della Torraccia, the final objective of the February fighting, was under American control.

THE CAPTURE OF MOUNT BELVEDERE cost the 10th Mountain Division a total of 923 casualties: 192 killed in action, 730 wounded, and one prisoner of war. The men of the 85th Regiment—who had been inspired by General Hays’s “always forward” talk—suffered more than half the total American casualties in the battle, with 470 killed and wounded. Total German casualties are unknown, but over 400 were taken prisoner. The original plans for the offensive had envisioned it taking as long as two weeks to drive the Germans off Belvedere and adjoining peaks; instead it took the 10th five days.

There hadn’t been much good news from the “forgotten front” in Italy since the previous summer’s fighting. While the Allied armies in western Europe drove the Germans from France and Belgium, beat back the Nazi offensive in the Battle of the Bulge, and pushed into Germany itself, the Italian front had settled into winter stalemate yet again. The attack on Belvedere changed that, and the men of the 10th Mountain Division were the heroes of the day. “The recent successes of the Fifth Army in the area around and including Mount Belvedere, west of the Bologna-Pistoia road, were achieved by the American Tenth Mountain Division,” the New York Times reported on February 25:

Made up of especially trained fighters, many of whom were formerly skiers, mountain-climbers and forest rangers, the division from Monday through yesterday secured not only the key feature of Mount Belvedere itself but also Mount Gorgolesco and the Mount della Torraccia ridge.

The 10th would remain in the vanguard of the Allied drive northward into northern Italy’s Po Valley and the Alps beyond until the German surrender in Italy on May 2. In four months of combat, the division never failed to take its objectives, nor were the mountain troopers ever driven from any objective they had taken. Their enemies knew and respected their qualities. Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander of German forces for most of the Italian campaign, wrote after the war: “To my surprise—in deep snow—the remarkably good American 10th Mountain Division launched an attack against the left flank of [the German defensive line], which speedily led to the loss of the dominating heights of Monte Belvedere.”

For at least one young soldier (and probably many more), Belvedere represented a coming of age. It’s appropriate that he should have the last word. Corporal Marty Daneman, having just turned 20 in the days before the battle, was no longer the callow youth who only a month earlier had written fiancée Lois that he was “anxious to get in a hot spot” to test his courage. The corporal was coming to grips with a new and hard-won maturity. Belvedere had left him with an abiding hatred of war. That—and a conviction that the war he was fighting was nonetheless necessary:

I still say – better to have it happen here than back home. I still say that the tragic price we pay is worth it and I would live thru it again & again to insure the fact that you & our kids won’t have to endure another war. And so my 20th birthday rolled around & I feel 30.

Corporal Daneman would survive the war to marry Lois in August 1945. ✯

This story was published in the February issue of World War II.