The American arsenal of democracy delivered a huge number and variety of bombers during World War II. Among them were Boeing’s B-17 Flying Fortress and B-29 Superfortress; Consolidated’s B-24 Liberator series; North American’s B-25 Mitchell; and Martin’s B-26 Marauder. Excepting the B-29, all flew against every Axis power, from the Pacific and Aleutians to North Africa and Europe. But one latecomer barely got off the bench to play just before the final whistle: Consolidated’s little-known B-32 Dominator. If it’s remembered much at all it might be because of an unfortunate fact: a crewmember aboard a B-32 became the last United States combat fatality of the war.

Consolidated already had become a prominent factor in World War II aviation, producing not only the Army B-24 and Navy PB4Y series, but also the classic PBY Catalina and PB2Y Coronado flying boats. So when the Army Air Forces (AAF) sought another heavy bomber to fight alongside the B-29, it gave the San Diego firm the nod over four other contenders, giving the company the XB-32 order in September 1940. The planned aircraft would use the same 2,200-hp Wright R-3350 engines developed for the B-29 and share the concepts of a pressurized fuselage and remote-controlled gun turrets. The Army inspected the mockups and gave the go-ahead for prototypes in January 1941.

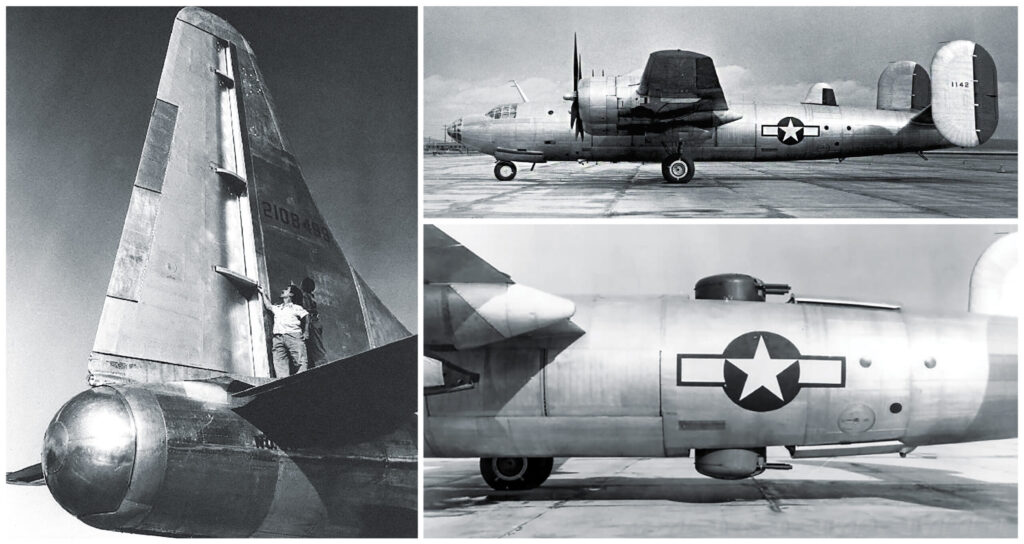

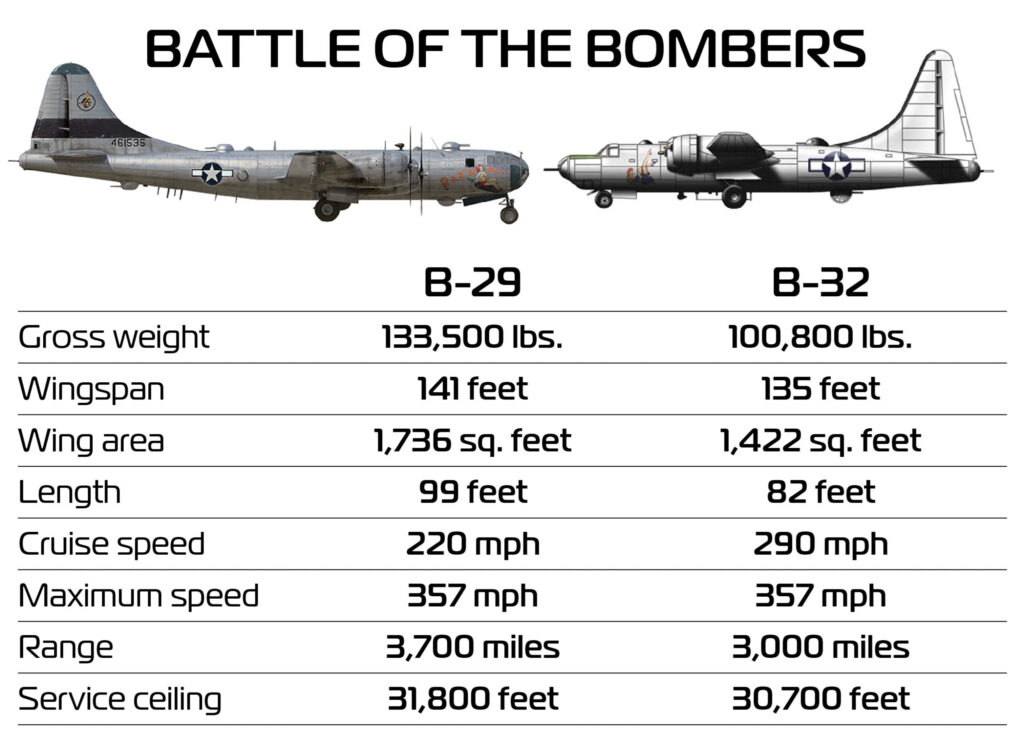

Showing some Liberator influence, the first XB-32 sported the same high-aspect-ratio Davis wing and twin tails. The inboard engines had reversible propellers to shorten the landing distance. However, the B-32’s rounded fuselage was aerodynamically sleeker than the B-24’s slab-sided airframe. Despite its similarity to the “very heavy” B-29, the Consolidated was designated a heavy bomber with an ultimate gross weight of 100,800 pounds versus 133,500 for the Boeing.

Dubbed the Dominator, the prototype XB-32 made its first flight on September 7, 1942, two years after Consolidated signed the contract. It crashed in May 1943, but the second prototype flew in July and the third in November. By then the configuration had seen some changes. It now had more of a “stepped” canopy, and the B-24-type twin tail had transformed into a high single tail similar to that of the Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer.

The program saw more changes as it progressed. Consolidated eliminated the pressurization and replaced the unreliable remote-controlled gun turrets with five manual twin mounts and the original three-blade props gave way to the B-29’s four. During flight tests in October 1944, Colonels Mark E. Bradley and Osmond J. Ritland reported a mixed impression of the aircraft, but noted, “Although the B-32 is a comparatively easy airplane to fly, it is not considered a pleasant airplane because of poor ‘feel,’ noise and vibration, excessive trim change with use of flaps, high landing and takeoff speeds.” They said that the Dominator “will not be a popular airplane with the services.”

Meanwhile, the B-32’s development had overlapped the 1943 merger between Consolidated and Vultee that led to the emergence of a new company, Convair. However, the corporate amalgam exerted little if any influence upon the Dominator program as the bombers began to roll off the production line at the company’s new plant in Fort Worth, Texas.

In all, the AAF ordered 1,500 Dominators. Convair delivered the first production model in September 1944, but it soon suffered a nose wheel collapse on landing. Other bombers were delivered in November with unit-size introduction in late January 1945. By then it had become clear that the B-29 did not require a backup, so the Army directed that 40 B-32s be delivered as unarmed transition trainers. One detachment received orders to the Philippines for operational evaluation, though it was clear that the Dominator would see little combat. In the U.S. that summer, B-32s averaged a mere three hours flying time per month.

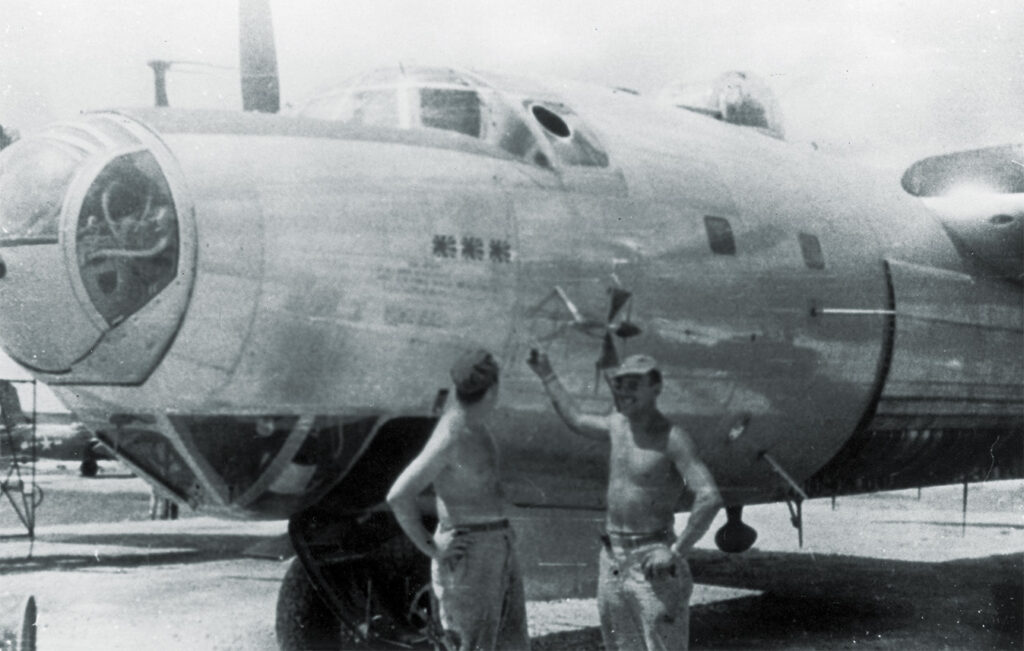

The Pacific-bound Dominators set out on an 8,300-mile global trek in May 1944, leaving Fort Worth for Mather Field, California, then flying on to Hickam Field, Hawaii, and from there to Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands, Guam in the Marianas, and on to Clark Field, Luzon. There the B-32 crews joined the 386th Bombardment Squadron of 312th Bombardment Group. The group was a Pacific old-timer under Lt. Col. Selmon Wells that had been flying Douglas A-20 Havocs. Just 25, Wells had flown with the group since late 1942 and had a wealth of combat experience.

The Dominator became the designated hitter for the 312th and took on a heavy bombardment role that was quite different from the light attack duties the squadron had been flying with its A-20s. One of the crewmembers making the transition to the Dominator was Staff Sgt. Julius Kossor, who noted in his diary that he was glad to leave the Havocs behind: “really had some close calls these last few missions,” he wrote.

In May the squadron’s commanding officer, Major “Pinky” Wilson, received his orders to return to the States. An original member from the squadron’s inception in October 1942, Wilson had flown 109 missions and amassed 320 hours, one of the group’s most notable records. Captain Ferdinand L. Svore replaced Wilson as new CO. He had arrived in July 1944 and served as squadron and group operations officer before taking command. On May 30, shortly after Svore’s promotion, the squadron ceased Havoc operations to begin B-32 missions. To prepare, ground staff visited the B-24-equipped 43rd Bomb Group to learn heavy bombardment organization and procedures. New personnel “began to trickle in” from the first of June, Kossor noted.

In that period Kossor wrote, “Our A-20s, with their pilots and gunners, were transferred out and assigned to the other three squadrons in the group. New crews, factory representatives and specialists joined the squadron, and preparations were under way to convert the 386th Bomb Squadron (Light) into a very heavy bomb squadron.”

The day before it ended all Havoc missions, the squadron flew the first B-32 raid of the war, an attack north of the Philippine capital of Manila. In a display of unit pride, the squadron report noted, “The outstanding raid of the month, and probably the most notable in this theatre, was the B-32 strike on May 29th. Two of three B-32s assigned to the 386th were sent on a mission to Antatet in the Cagayan Valley. If the Japs below took time to peek out of their foxholes, they must have been amazed to see eighteen 1,000 pounders dropped from only two planes. Bombing from 10,000 feet was excellent. All bombs were 100 percent on the target, scoring direct hits on a house and damaging a large tin-roofed warehouse.

“This, the first B-32 raid in the world, was the forerunner of future operations in the Pacific,” the report concluded, not quite accurately.

After addressing engine problems and deferred maintenance, in June the squadron’s three Dominators flew ten two-plane missions to drop 135 tons of bombs, mostly on Formosa (today Taiwan). Kossor flew his first heavy bomber mission on June 13 in one of two Dominators that struck a Formosa airfield. From the ball turret Kossor had “a perfect view of the target. Three bombs made direct hits on the runway. Others all around the field—no fighter interception and no damage to our two planes.” He judged the Dominator to be “a good fast ship.”

By the end of June, the squadron, now equipped with three B-32s and a C-47B for miscellaneous duties, had logged ten missions (20 sorties) for 105 combat hours. The combat tests ended in July and other crews began making the transition to the new bomber. Then on July 30 the advance echelon began moving to Okinawa while the rest waited for a fourth B-32 to arrive. The unit diary noted, “All we had was the promise that more were on the way.” And there were: five B-32s headed overseas in July, and nine more in August. Still, that meant there were only 10 to 16 Dominator crews overseas between June and August, versus 1,200 or so B-29 crews.

The squadron properly noted that August 1945 was “an eventful month in world history resulting in a month of impatient waiting” for the 55 officers, 370 enlisted men and nine civilian technicians on the roster. On August 8 the bombers and supporting transports left Clark Field in the Philippines for Okinawa and landed with bombs aboard at Yontan. Shortly afterward the unit moved to nearby Kadena Airfield, already home to three bomb groups and a fighter group. The support staff’s “water echelon” sailed by ship and learned about the atomic bombs dropped on Japan along the way. A squadron officer wrote, “Despite the fact that the war was unofficially over, the 386th carried on a private war with the Empire of Japan.” On August 15 anti-shipping strikes were recalled upon Tokyo’s surrender announcement.

However, the new arrivals still had work to do. On the 16th, reconnaissance missions scouted possible landing fields in Japan for the airborne troops who were due to arrive shortly. One Dominator turned back with engine problems but the other, Hobo Queen II, completed the flight.

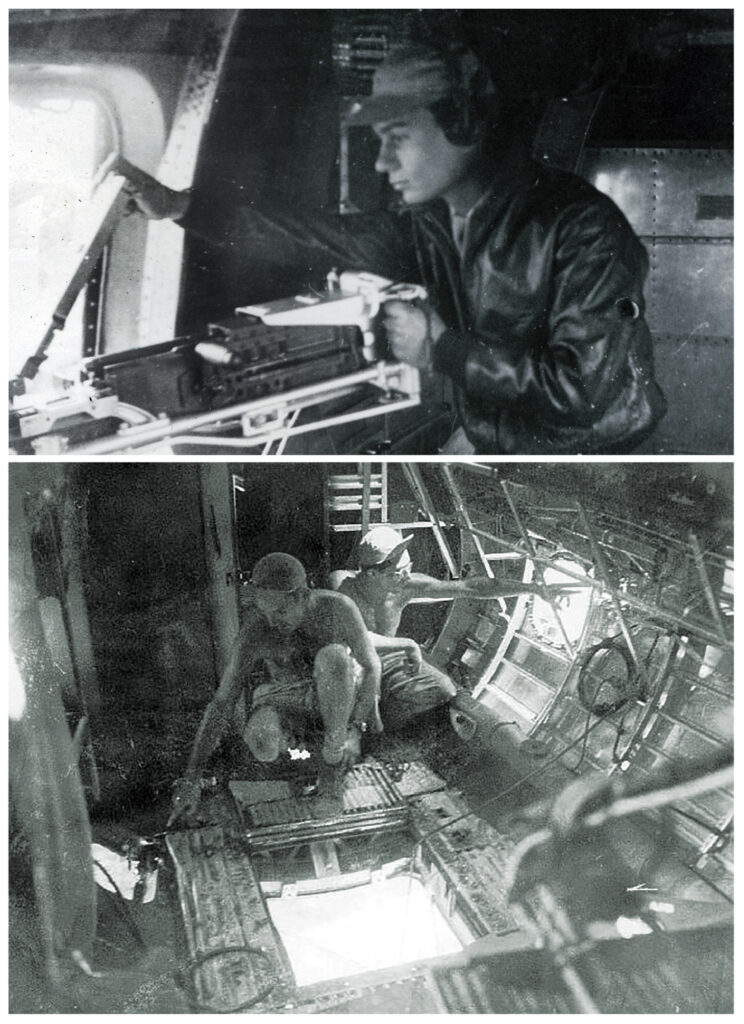

On August 17 the 386th launched four photo sorties around Tokyo under the youthful Colonel Wells. During the two hours over Japan the individual bombers were harassed and attacked by flak and Japanese Navy pilots who ignored the surrender announcement that had gone out two days before. Sergeant Kossor said it was the “roughest mission I ever had.” He was flying with Wells, who had told him to leave his ball turret up because it created too much drag when lowered. Then Japanese fighters attacked and Kossor had to scramble to get the turret down. “They attacked us from each wing, and then flew under my ball as they passed,” he noted. “A perfect target, but because I obeyed orders we may have crashed in Tokio. Then we got hit with flak. It was heavy and damn accurate.” Anti-aircraft fire put shrapnel into a wing, but Wells proceeded to Yokosuka where he found the flak was even thicker but experienced little threat from fighters.

That wasn’t the case with two other Dominators. In the Yokosuka area they aborted their photo runs due to cloud cover but conducted shootouts at 20,000 feet. The gunners claimed one fighter destroyed and another damaged before heading seaward with gunfire damage to a wing.

The fourth bomber had an even rougher time. In a 15-minute set-to, several Japanese ganged up on the Dominator from six o’clock. An upper turret gunner set his sights on the closest and watched his tracers sparkle on the green airframe. Obviously stricken and streaming smoke, the assailant dropped into the undercast. But the tail turret failed and the Japanese noticed the weakness. They renewed their attacks from astern although the bomber escaped without serious damage and landed with the others about four hours later. The unit diarist recorded, “Approximately ten fighter planes attacked the formation, resulting in two probables for our side.”

Of greater concern to Far East air forces was what Japanese fighter opposition meant. Presumably the interim agreement made before the formal surrender allowed Allied aircraft full access to Japanese airspace. Did the violent responses indicate a change in Tokyo policy or were the intercepts flown by dissidents who refused to surrender?

The latter proved the case. Years later a prominent Japanese Navy ace, Lieutenant (j.g.) Saburo Sakai, explained his rationale for opposing the B-32 flights. His commanding officer had stated that if any pilots wanted to intercept the Americans, he would look the other way. When the B-32s came into sight that day, Sakai and his fellow pilots decided to attack them. “While Japan did agree to the surrender, we were still a sovereign nation, and every nation has the right to protect itself,” Sakai asserted. He claimed that the Japanese did not know the B-32s’ intentions and that the Americans should have waited before sending more airplanes over Japan. “They should have waited and let things cool down.”

The next day, the squadron flew two more photo sorties over Tokyo. The Dominators flew with extra observers and photographers to verify the situations at major airfields. The planes had completed their routes when crewmen noticed fighters airborne from the Atsugi airfield. “Fourteen Jap fighters engaged our bombers in twenty minutes of aerial combat,” the unit diary noted. “Two enemy planes were shot down and two probably destroyed. Gunners Houston and Smart were the sharpshooters.”

Lieutenant James Klein’s Hobo Queen II held an altitude advantage over Lieutenant John Anderson’s unnamed bomber, which was some 10,000 feet below. Anderson’s tail and top forward gunners put dozens of .50-caliber rounds on target, seeing two dark green fighters gush flames or explode. The nose gunner swapped gunfire with Lieutenant Sadamu Komachi, survivor of the Darwinian winnowing Japanese pilots had experienced since Pearl Harbor. The veteran shot out the Dominator’s port inboard engine, blew the plexiglass off the top rear turret, and damaged the rudder.

During the shootout one of the photographers, Staff Sgt. Joseph Lacharite, received wounds in both legs, so Sergeant Anthony J. Marchione, a young Pennsylvanian on his first B-32 mission, laid him on a cot and took over the first-aid effort. Moments later a 20mm shell exploded in the fuselage, inflicting a massive chest wound on Marchione. Five of his fellow crewmen tried to keep him alive, applying pressure while administering plasma and oxygen.

Attended by his friends, Tony Marchione died at age 19, high over Japan and far from his home in Pennsylvania. The two bombers landed at Kadena that evening, Anderson’s making it on three engines.

Anthony Marchione almost certainly was the last American killed in combat during the Second World War. Historian Stephen Harding wrote a bittersweet account of the young sergeant’s life, death and family in his book, Last to Die. It remains the definitive account of Marchione’s death. “

The War was supposed to be over Aug. 15, but our men are still gettin’ killed,” Kossor griped in his diary. “To us it isn’t over for some time yet. Nobody’s celebratin’ ‘The End’ over here. Because the war is supposed to be over, we do not get combat time for these missions. We got the rotten deal of flyin’ ’em ‘on the house!’”

Ten days later the unit diary noted, “August 28 was probably the saddest day in the history of the 312th Group.” In two disastrous crashes, 15 officers and men were killed. One plane was taking off when it crashed at the end of the runway. There were no survivors. The other B-32, after completing a recon mission, developed engine trouble and flew to within 175 miles of Okinawa on two engines. Two crewmembers died in the bailout but the rest survived and “spent a pleasant cruise on two destroyers and returned a week later.”

After the signing of the peace treaty on September 2, a bomber from the 386th Squadron departed for the States, representing the first airplane from Fifth Air Force to return from Japan. The unit diarist closed, “So ended the glorious history of the 386th Bomb Squadron; activated three years ago in Savannah as a dive bomb outfit; flew fighter patrols over New Guinea in P-40s; bombed and strafed New Guinea and the Philippines in A-20s; received a Presidential Citation for operations against Formosa; flew the first B-32s in combat and participated in the last aerial combat of World War II.”

The war’s finish also spelled the end to the B-32. The Army Air Forces no longer needed the Dominator. Only 114 had rolled out of the Fort Worth Consolidated-Vultee plant by the time production ceased—a far cry from the 1,500 originally planned. Today not a single B-32 remains.