The saga of Two Ton Tessie typified the stellar service of countless Allied bombers in the European theater.

Actress Gloria Swanson embodied the ideal of a movie star. Beautiful, magnetic, talented—she defined Hollywood glamor in the silent-film era. By the 1940s Swanson had been replaced as a box office draw by newer names and faces, but she was still an American icon. When she visited the Willow Run Bomber Plant near Detroit, Mich., in October 1943 at the height of World War II, it was a very big deal.

The mighty Willow Run plant was an icon in itself. Dignitaries and movie stars frequently visited to see Consolidated B-24 Liberators roll off its automotive-style assembly line at the astonishing rate of one bomber every hour. From President Franklin D. Roosevelt and General Henry “Hap” Arnold to Walt Disney and Clark Gable, famous figures regularly turned up at the plant. Whenever celebrities visited Willow Run, it was customary to have them sign a ship fresh off the assembly line while news cameras flashed. Glamorous Gloria was no exception, gracing B-24H serial no. 42-52117 with her signature as the big bomber left the factory to begin its journey into battle.

But what happened to this particular Willow Run Liberator after the crowd and the cameras went home?

As 42-52117 rolled off the line in the fall of 1943, the U.S. Army Air Forces was preparing for a year of “maximum effort” in the European Theater of Operations. Using the heavy bombers being mass-produced at factories such as Willow Run, the Fifteenth Air Force planned to launch long-range strategic bombing missions against critical Axis targets in central and eastern Europe. It was important to cripple Nazi Germany’s fighter aircraft bases and factories, as well as disrupt fuel production and supply lines. Newly acquired air bases in Italy would provide access to targets that were out of range of the Eighth Air Force stationed in England.

On October 27, 1943, the new B-24 was sent to Bruning Army Air Field in Nebraska, where it was assigned to a crew of the 719th Bomb Squadron, 449th Bomb Group, 47th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), under the leadership of pilot George T. Fergus Jr. On November 17 plane and crew were transferred to Topeka, Kan., where the crew continued to get acquainted with the bomber on test flights over the U.S. Then in December, along with the rest of the 449th Bomb Group, Fergus and company flew their ship overseas via South America and North Africa to Italy.

Grottaglie, in the boot heel of Italy, had been recently captured from the enemy, and the air base there looked like it had been thoroughly stomped on. Bombed by Allied forces prior to capture, the buildings had been stripped clean by fleeing German forces and the local population. For a time, the B-24 crews of the 449th had to sleep on the floor, wash from their helmets and share one four-hole latrine among the group.

The men swiftly got the base in order, celebrating Christmas 1943 and New Year’s 1944 in rough comfort in their new home. The local residents were friendly, and each crew attracted a young Italian helper from among the local boys, who would assist with barracks chores in return for payment in chocolate and cigarettes. One 449th airman recalled being invited to share a meal at their young helper’s home and enjoying the family’s hospitality while seated around an open fire pit at the center of their stone dwelling.

The base was menaced periodically by lone enemy aircraft, most likely from German airfields in the north of Italy. The men nicknamed one frequent flier Bed Check Charlie. He would shoot at the base and the B-24 bombers parked for the night. But luckily, according to one airman, “His aim was lousy.”

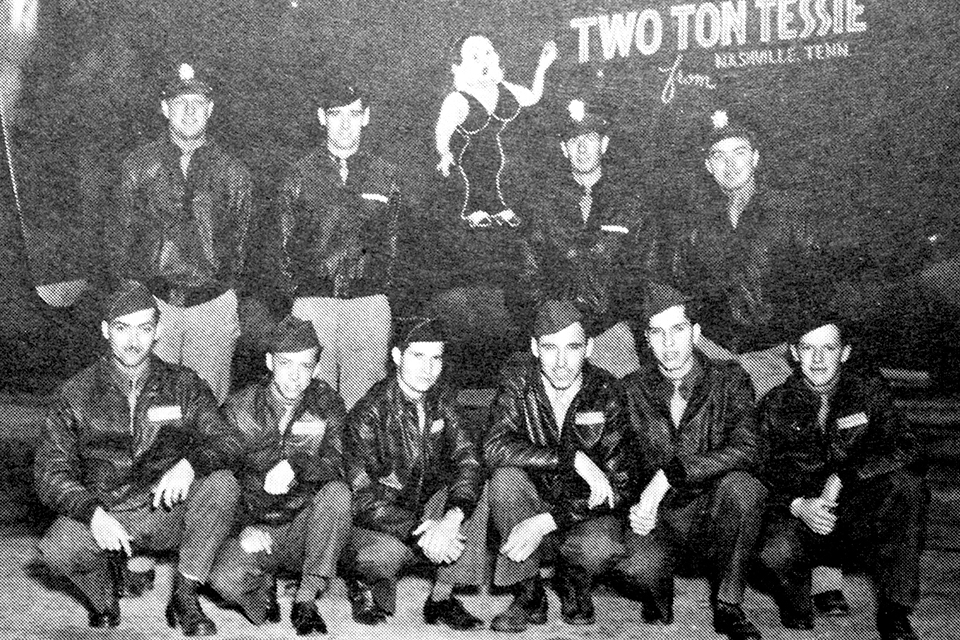

At some point in their early acquaintance with 42-52117, Fergus’ crew decided to give the Willow Run bomber a name. They christened her Two Ton Tessie from Nashville, Tenn. and added colorful nose art of a buxom blond.

In January 1944, the 449th Bomb Group’s B-24s began flying missions over enemy territory. Two Ton Tessie flew her first mission on January 10 against a railroad marshaling yard in Skopje, Yugoslavia. Over the next few months, she went on to bomb strategic targets in Italy, France, Yugoslavia, Austria, Bulgaria and Romania. Two Ton Tessie’s crews targeted enemy aircraft factories, ball bearing plants, airfields, marshaling yards, roads and bridges, as well as the famous Ploesti oil fields and refineries in Romania, with their heavy fighter defenses and dreaded anti-aircraft flak train.

The 449th’s Liberators were accompanied by various fighter squadrons on their missions, including those of the 332nd Fighter Group, the famed Tuskegee Airmen—the first African-American military pilots to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Fifteenth Air Force bomber crews, including those of the 449th, appreciated their skill and bravery. They called them the “Red Tails” for their fighters’ red-painted empennage and even the “Red Tail Angels.” In the words of 449th airman George C. Henry, “We owe them so much.”

Two Ton Tessie flew 22 missions without incident until April 30, 1944, when a different crew was assigned to her, led by pilot Nelson Wood. The day’s mission began well, as the bombers formed up and headed for a target at Alessandria, Italy. With no flak or enemy fighters and the comforting hum of Tessie’s four engines, the mission promised to be, in the words of ball turret gunner William Hamill, “a piece of cake.”

But just before they arrived at the IP (the initial point of the bombing run), the no. 1 engine stopped and the propeller had to be feathered. The crew jettisoned their bombs in an effort to lighten the airplane’s load and keep up with the formation. Tessie was dropping farther and farther behind when the no. 2 engine also gave out, and the ship began to lose altitude.

As the crew watched the other bombers fade into the distance, they decided their best bet was to head for Allied air bases on the island of Corsica. They maneuvered through scenic mountain valleys while steadily losing altitude, and in an attempt to stay aloft jettisoned guns, ammo, flak suits…everything but their parachutes. As they passed over the Italian city of Genoa, they were low enough to see people walking in the streets.

They made it to a Royal Air Force base on Corsica on the two functioning engines, and as they approached they could see some Supermarine Spitfires parked near the landing strip. But Tessie’s hydraulic system was out, and one of the wheels on the landing gear was deflated. Upon landing, the Liberator veered out of control and plowed right through two of the Spitfires and into an open field, where the bomber came to a halt.

The crew was unhurt, but ball turret gunner Hamill recalled, “We climbed out of our wreck realizing that we had ruined two precious Spitfires. We were very shortly looking into the faces of a dozen or more unhappy British pilots.”

Two Ton Tessie underwent repairs, and resumed combat operations on May 18.

Tessie’s fateful 30th bombing mission, on May 29, targeted a German aircraft factory in Wiener Neustadt, Austria, near Vienna. On that beautiful spring morning, 35 B-24s of the 449th took off from Grottaglie and rendezvoused with more bombers from the 450th Bomb Group. With excellent fighter escort provided by P-38 Lightnings and P-51 Mustangs, the group continued in formation to the target.

Tessie was manned that day by her usual crew of 10: pilot George Fergus, copilot James Kervin, navigator Joe Truemper, bombardier Foss Robinson, flight engineer Floyd Caldwell, radio operator George Littlejohn, assistant engineer and waist gunner Russell Bolden, ball turret gunner Harold Fox, waist gunner Donald Walker and tail gunner Edward Cooley. Since the bomber had recently been overhauled by the line crew, the airmen were confident she was in tiptop shape. The engines were running smoothly, in the words of copilot Kervin, “purring like four kittens.”

About five hours into the mission and well over enemy territory, Tessie lost the supercharger on the no. 2 engine. Fergus, Kervin and flight engineer Caldwell thought they could stay with the formation and continue the mission, but as they approached the IP a second turbo blew. Unable to keep up with the formation, Tessie fell behind. Knowing they were a sitting duck for the Luftwaffe, the crew jettisoned their bombs. Within minutes, enemy fighters (reportedly Focke-Wulf Fw-190s) found the struggling bomber and commenced an attack, knocking out the no. 1 and 2 engines. The B-24 took hits in the tail section and bomb bay; hydraulic lines were severed and it caught fire, sending Tessie into a lazy spiral at 19,000 feet.

Fergus gave the order for the crew to abandon ship. The last words heard over Tessie’s intercom were from navigator Truemper, saying, “When you hit the ground take a heading of 180 and start walking. Good luck.”

“All 10 crew hit the silk,” recalled copilot Kervin. “As I floated to earth I saw in the distance Two Ton Tessie slowly and majestically, in flames, gliding into oblivion.”

While Tessie’s service came to an end that day, her 10 crewmen survived the jump to become German POWs. All were liberated at the end of the war.

Two Ton Tessie and the 449th Bomb Group played a part in a key Allied strategy that turned the tide toward victory in the European theater. During a spell of exceptionally good weather in February 1944, American bombers hit nearly every German fighter assembly plant. Although fighter production didn’t completely cease, the work of that week helped swing the balance of air power in the Allies’ favor. In the spring of 1944, Allied bombers began attacking the beating heart of the German war machine: its oil fields, refineries and fuel supply lines. Peak production of B-24 Liberators at mighty Willow Run, along with bombers like Two Ton Tessie and the airmen of the 449th, contributed to that victory, signaling a turning point in the European war.

Glamorous Gloria would have been proud. ✯

World War II buff Jeannette Gutierrez is a volunteer at SaveTheBomberPlant.org. For further reading, she suggests: “Maximum Effort”: A History of the 449th Bomb Group World War II, by members of the 449th Bomb Group Association; and Willow Run (Images of Aviation), by Randy Hotton and Michael W.R. Davis.

This feature originally appeared in the July 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!