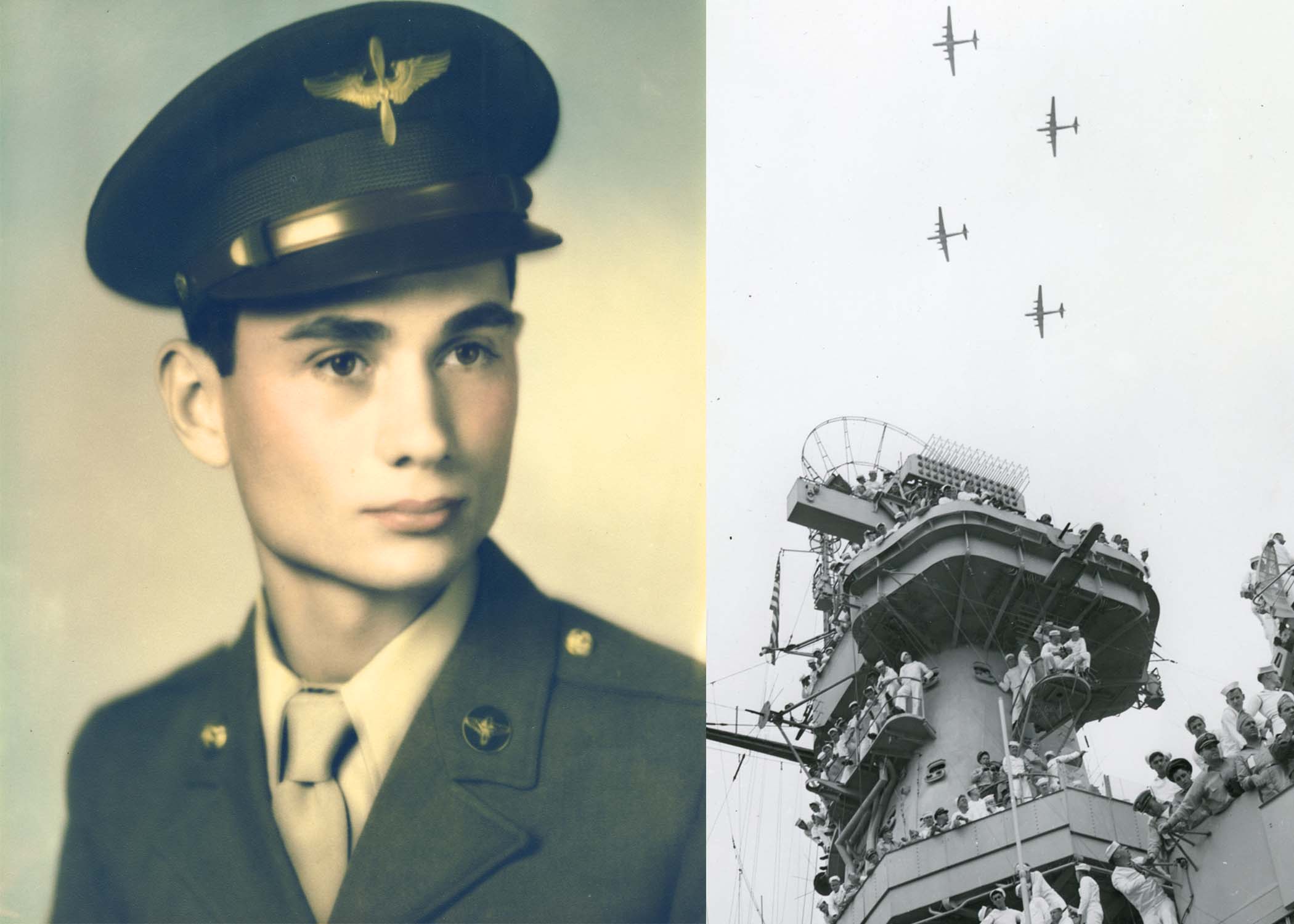

August 18, 2020 marked the 75th anniversary of the death of the last American service member killed in combat in World War II. His name was Anthony Marchione. He’d just turned 21 and was killed by renegade Japanese fighter pilots three days after the August 15 ceasefire between the Allies and Japan went into effect. The following is an excerpt from Marchione’s story as described in the book, “Last to Die” by former Military History editor Stephen Harding.

Just before 7 o’clock on the morning of August 18, 1945, a huge, four-engined aircraft moved slowly onto the end of a 7,000-foot-long runway at Yontan airfield on the southwestern coast of the island of Okinawa. Though the machine’s long, cylindrical fuselage, tall tail, and high, narrow wings gave her a certain elegance of line, on the ground she was ponderous. Loaded with fuel and men, she rocked heavily on squat tricycle landing gear as she turned her nose into the wind, then shuddered to a halt as her crew made the last preparations for takeoff.

The aircraft, a B-32 Dominator heavy bomber of the U.S. Army Air Forces’ 386th Bombardment Squadron, was one of four scheduled to depart that morning on what everyone in the unit hoped would be a routine photo-reconnaissance mission over Tokyo. At that point in World War II “routine” should have been a given—Japan had accepted the Allies’ terms for unconditional surrender four days earlier and President Harry S. Truman had ordered the suspension of all offensive operations against Japan on August 15. Yet four B-32s flying a photo-recon mission over Tokyo two days later had been attacked and damaged by Japanese fighters whose pilots had apparently not heard of the cease-fire ordered by Japan’s Emperor Hirohito or, more ominously, had chosen to ignore it. At the early morning briefing for the August 18 mission the Dominator crewmen had been told to assume they’d be flying into what might still be very hostile territory.

With final checks completed, the pilot of the lead B-32—24-year-old 1st Lieutenant James L. Klein—released the aircraft’s brakes and smoothly advanced the throttles. The low growl of four idling Wright R-3350 radial engines quickly swelled to a gut-rumbling howl, and the Dominator—the racy nose art painted on the left side of her forward fuselage identified her as Hobo Queen II—rapidly picked up speed as she surged down the runway. When the bomber hit 130mph abreast of the 4,500-foot marker Klein gently lifted the nose; the aircraft was instantly transformed from a lumbering, earth-bound behemoth into something far more graceful. Her gear coming up and flaps retracting, Hobo Queen II roared over the coral pit at the end of the airstrip and began a climbing 180-degree turn.

With the runway clear the pilot of the second Dominator, 27-year-old 1st Lieutenant John R. Anderson, moved his bomber from the taxiway into take-off position. The aircraft shook as Anderson did a last engine run-up and the acrid smell of burning high-octane aviation gasoline wafted through the fuselage. Seconds later, her huge paddle-bladed propellers clawing the already-humid air, the B-32 began the sprint down Yontan’s runway.

As Anderson’s Dominator picked up speed, four young men sat huddled on a low, cot-like settee fixed to the port side of the fuselage in the bomber’s rear cabin. Two of the men were gunners; once the Dominator was airborne they’d take their places, one in the tail turret and the other in the rear-most of the B-32’s two top turrets. The other two men—29-year–old Staff Sgt. Joseph Lacharite and 20-year-old Sgt. Anthony Marchione—were not members of the bomber’s crew. They were assigned to the Yontan-based 20th Reconnaissance Squadron, Lacherite as an aerial photographer and Marchione as a gunner/photographer’s assistant. At their feet rested a heavy canvas bag containing the K-22 camera they would use to record the images that were the ultimate purpose of the day’s mission.

That mission—designated Number 230 A-8—was to photograph several Japanese military airfields sited to the east and northeast of the sprawling Tokyo metropolitan area. The reason was twofold: first, to verify that Japanese aircraft were being kept on the ground in compliance with the cease-fire terms; and second, to determine whether the fields were in good enough condition to handle the heavily laden Allied transports that would help bring in the first occupation troops. On paper the mission seemed straightforward: The four B-32s were to cross the assigned recon area at 20,000 feet and two miles apart, following parallel flight lines that ran directly east and west. When they finished “mowing the lawn,” they would begin the return leg to Okinawa. The 1,900-mile round trip—roughly equivalent to a flight from Los Angeles to Seattle and back—would take 8 to 10 hours if all went well.

As soon as his B-32 was airborne and in her own climbing turn Anderson headed toward Klein’s Dominator, clearly visible ahead, the already bright morning sun glinting off the lead bomber’s uncamouflaged aluminum skin. The two other aircraft soon joined up, and in loose echelon formation the four B-32s began a gradual climb toward their cruising altitude and pointed their noses toward Tokyo.

________________________

At that same moment, some 900 miles to the northeast of Yontan, Emperor Hirohito and his senior advisers were most probably wondering if another Japanese city—perhaps even Tokyo itself—would soon disappear beneath a roiling mushroom cloud.

Hirohito had been under no illusion that his August 15 radio address announcing the decision to surrender would be immediately accepted by all senior members of the government and the military, yet even he was shocked by the events that unfolded in the hours and days following the broadcast. The announcement had sparked an army-led coup intended to reverse the emperor’s surrender order, and naval and air units at various points around the country were still in open revolt, vowing to fight on to the last man. Should such pointless and ultimately futile military action convince the Allies that Hirohito was unable to enforce his surrender decision or, worse, that his government’s agreement to the Allied ultimatum was simply a delaying tactic meant to give Japan more time to organize its defense against an Allied invasion, the consequences for Hirohito’s much-diminished empire could well be catastrophic.

_________________________

Among those diehards about whom Hirohito should have been most worried were several of the finest fighter pilots in the Imperial Japanese Navy. On the morning of August 18 the men—members of the elite Yokosuka Kokutai (Air Group) based just 24 miles south of the emperor’s Tokyo palace—had agreed to commit mutiny for the second time in as many days.

The Yokosuka Kokutai’s primary purpose by this point in the war was the development and testing of naval aircraft, which meant that among its members were some of the most experienced, talented and successful pilots in what was left of Japan’s naval air service. As a result, the unit was also tasked with aiding in the air defense of the greater Tokyo-Yokohama region. Over the preceding months the Yokosuka Kokutai’s pilots had joined in the fierce defense of the east-central part of their homeland against the hordes of American B-29 bombers and Allied land- and carrier-based strike aircraft that had been systematically reducing the military facilities, harbors, industrial centers and key cities of eastern Honshu to smoking rubble.

The willingness of the Yokosuka Kokutai’s pilots to continually launch themselves at the overwhelming numbers of enemy aircraft appearing daily—and nightly—over their nation implies a level of patriotic dedication verging on fanaticism. And Hirohito’s August 15 announcement of his decision to surrender to the Allies did little to dampen that nationalistic and professional fervor. Despite official orders from Imperial Japanese Navy headquarters to cease attacks on Allied aircraft, many of the Yokosuka Kokutai’s pilots felt—as did other army and navy aviators elsewhere in Japan—that the nation’s airspace should remain inviolate until a formal surrender document had actually been signed. That belief had led several Yokosuka pilots to attack the B-32s engaged on the August 17 mission, and the passage of 24 hours had done nothing to cool their martial zeal. They were ready to once again disobey direct orders and punish any Allied airmen who came within range.

_______________________

While they could not have known of the political turmoil in Tokyo or the mood of the Yokosuka Kokutai’s pilots, the men aboard the Dominators winging ever closer to the coast of Honshu on August 18 were only too aware of the mission’s potential for disaster. Most had seen enough combat in the past months to have an inherent, visceral distrust of their enemy, an emotion validated in their minds by details revealed at the morning’s pre-flight briefing of the Japanese fighter attacks on the B-32s involved in the previous day’s mission. Added to the airmens’ underlying unease was the fact that their own defenses had been reduced by half; about five hours after that morning’s takeoff from Yontan two of the Dominators had aborted the mission due to mechanical problems and returned to Okinawa. Adding insult to injury, both Klein’s aircraft and Hobo Queen II were dealing with balky turrets and inoperable guns.

Sadly, Mission 230 A-8 would ultimately play itself out in ways that would exceed even the most pessimistic crewmember’s fears. Before the day ended there would be one last desperate air combat between Americans and Japanese; that combat would come perilously close to reigniting a war that seemed all but over; and a young man would quietly bleed to death in the bright, clear skies above Tokyo, in the process gaining the dubious distinction of being the last American killed in air combat in World War II.

Stephen Harding is the former editor of Military History. He is the author of 11 books, including the New York Times bestseller THE LAST BATTLE, LAST TO DIE and THE CASTAWAY’S WAR.

For more great stories, subscribe to Military History magazine here and visit us on Facebook: