On September 14, 1862, fighting broke out on South Mountain, Md., as portions of the Army of the Potomac clashed with Army of Northern Virginia troops holding passes over the mountain. On the 15th, the day after particularly heavy fighting at Fox’s Gap, Ohio troops were assigned to a burial detail on that contested cleft. As it was a task they did not particularly like, they sought a shortcut by dumping a number of Confederate bodies down a well in front of a cabin.

The cabin and well belonged to an old farmer named Daniel Wise. Realizing his well was ruined and being a shrewd codger, Wise made the most of a bad situation by contracting with 9th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside to continue the process for $1 a body. After depositing several more bodies, Wise sealed the well, earning himself a tidy sum.

Or so goes the legend.

Some versions of the tale claim that no damage was done because the well was dry or abandoned. Others claim farmer Wise was caught and made to put things right by removing the dead Confederates and giving them a decent burial. All accounts agree, at least, that Wise was paid for his troubles.

Most modern authors of books on the battle use the same source when relating the tale: History of the Twenty-First Massachusetts Volunteers. It was authored 20 years after the Battle of South Mountain by Charles F. Walcott, a member of the 21st. Since Captain Walcott was at Fox’s Gap on September 14 and 15, some historians presume that he witnessed the event. It is from the following account that most authors have based their narratives concerning Wise:

“The burial of a portion of the rebel dead was peculiar enough to call for special mention. Some Ohio troops had been detailed to bury them, but not relishing the task, and finding the ground hard to dig, soon removed the covering of a deep well connected with Wise’s house on the summit, and lightened their toil by throwing a few bodies into the well. Mr. Wise soon discovered what they were about, and had it stopped: and then the Ohioans went away, leaving their work unfinished. Poor Mr. Wise, anxious to get rid of the bodies, finally made an agreement with General Burnside to bury them for a dollar apiece. As long as his well had been already spoiled, he concluded to realize on the rest of its capacity, and put in fifty-eight more rebel bodies, which filled it to the surface of the ground.”

So now, let’s establish some facts.

The Fight at Fox’s Gap

Daniel Wise was a real person. He was born in Brunswick, Md., in 1802. On June 24, 1824, he married Mary Milly and together the couple had at least three children, a son named John, and two daughters named Matilda and Christiana. The census records for 1860 lists Daniel, Matilda, and John as residents of a modest, 1½-story whitewashed log cabin that stood at the intersection of the Old Sharpsburg Road (modern Reno Monument Road) and two mountain roads that more or less followed the mountain crest in a north-south direction.

Daniel’s wife seems to have perished (she was not listed in the 1850 census) and Christiana married and moved to start a family of her own. Among Christiana’s children was one of Daniel’s grandchildren, 5-year-old Anne Cecilia. Christiana often returned to visit and brought her children with her. At the time of the battle, Daniel Wise was 60 years old.

It seems that neither Wise nor his children were especially well off. In addition to farming, both Daniel and John eked out a living as day laborers and for a time as potters. Daniel Wise also earned a living as a “root doctor,” a local expert in folk medicine. According to the family’s oral history, on the morning of the battle the Wise family fled their cabin to seek safety elsewhere.

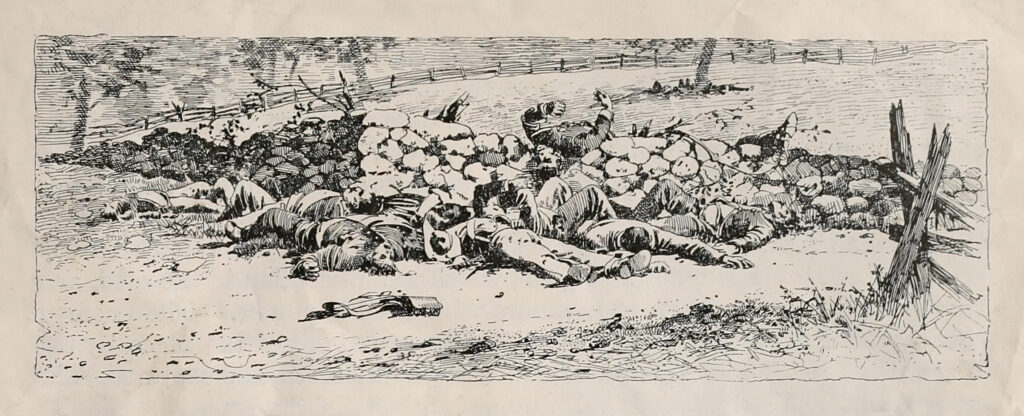

The fight at Fox’s Gap resulted in horrendous slaughter. The section of the Old Sharpsburg Road that passed over the ridge crest near Wise’s cabin would come to be known to the veterans as the Sunken Road. Regarding Confederate casualties, square foot per square foot, the Sunken Road at Fox’s Gap is proportionately every bit as bloody as its famous counterpart at Antietam.

One of the battle’s Confederate combatants, 1st Lt. Peter McGlashen of the 50th Georgia Infantry, later wrote: “When ordered to retreat I could scarce extricate myself from the dead and wounded around me. A Man could have walked from the head of our line to the foot on their bodies.”

This is borne out by a New York veteran of the battle. Remembered William Todd, the regimental historian of the 79th New York Infantry:

“Morning of the 15th dawned at last, and on such a sight as none of us ever wish to look upon again. Behind and in front of us, but especially in the angles of the stone walls, the dead bodies of the enemy lay thick; near the gaps in the fences they were piled on top of each other like cord-wood dumped from a cart. The living had retreated during the night and none but the dead and severely wounded remained….About noon we moved off the field, and on our way saw many more evidences of the battle. At one angle of the stone walls fourteen bodies of the enemy were counted lying in a heap, just as they had fallen, apparently. We referred to that spot as ‘Dead Man’s Corner.’”

The Wood Road, which ran southerly from Turner’s Gap to Fox’s Gap, was bordered on the east by a “stone and rider” fence near the intersection with the Old Sharpsburg Road. This type of fence consisted of a combination of stone wall with split rail fence over the top. William Todd may have referenced the intersection as “Dead Man’s Corner” as he was one of many who noticed a dead Confederate soldier hung up on the fence. “A curious sight presented itself in the body of a rebel straddling a stone wall,” wrote Todd, “he must have been killed while in the act of climbing over, for with a leg on either side, the body was thrown slightly forward stiff in death.”

Captain James Wren of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry had some time to view the battlefield on September 15 before his regiment headed for Sharpsburg. He not only noticed the dead Confederate on the fence, but another truly horrific sight. The following is from his personal diary:

“Just to the right of my skirmish line of yesterday were two Cross roads…and on our front there was a stone fence & behind that fence & in this cross road the enemy lay very thick. One rebel, in crossing the fence was Killed in the act & his Clothing Caught & he was hanging on the fence….At this place being the top of South Mountain, the Hospital was an awful sight, being a little house, by its self, & in the yard there was 3 or 4 Large tables in it & as the soldiers was put on it (that was wounded), the surgical Core Came along & the head of the Core had in his hand a piece of white Chalk & he marked the place where the Limb was to be Cut off & right behind him was the line of surgeons with their instruments & they proceeded to amputate & in Looking around in the yard, I saw a Beautiful, plump arm Laying, which drew my attention & in looking a Little at it, and seeing another of the same Kind, I picked them up & Laid them together & found that they are right & one a Left Arm, which Convinced me that they war off the one man & you Could see many legs Laying in the yard with the shoes & stocking on.”

Burial details began their gruesome work. Because Burnside’s 9th Corps occupied Fox’s Gap, the Union dead were buried first. By the end of the 15th, most of Burnside’s troops were off the mountain. Very few dead Confederates, if any at all, were buried on that day and, consequently, the bulk of the dead Southerners still lay above ground.

Burying the Dead

Many of the survivors of the fight at Fox’s Gap took the opportunity to tour the field, and many of the local citizenry came by to watch and collect curios. The Wise family’s well was located between Wise’s cabin and the Old Sharpsburg Road in plain sight of everyone using the road.

It is not unreasonable, then, to presume that had a 60-year-old man been occupied dumping dead Confederates down his family’s well, there would have been someone around to take notice. The truth is, no bodies were thrown down the well on September 15, 1862. That would instead happen on September 16, and farmer Daniel Wise had nothing to do with it.

It seems there was a witness to the event, Private Samuel Compton of the 12th Ohio Infantry, who wrote:

“On the morning of the 16th I strolled out to see them bury the Confederate dead. I saw but I never want to another sight. The squad I saw were armed with a pick & a canteen full of whiskey. The whiskey the most necessary of the two. The bodies had become so offensive that men could only endure it by being staggering drunk. To see men stagger up to corpses and strike four or five times before they could get a hold, a right hold being one above the belt. Then staggering, as the very drunk will, they dragged the corpses to a 60 foot well and tumbling them in. What a sepulcher and what a burial! You don’t wonder I had no appetite for supper.”

Obviously, conditions at Fox’s Gap on September 16 were much different from what they had been the day before. The area was definitely less crowded. One of the soldiers on burial detail was Private Michael Deady of the 23rd Ohio Infantry, who recalled that there were 75 men on burial detail at Fox’s Gap, a mixture of soldiers from several different regiments. It certainly seems that the Ohio men had a hand in dumping the bodies down the well.

If Private Deady’s veracity is trustworthy, the numbers of Confederates requiring burial was tremendous. After helping to bury 33 Union troops on September 15, Deady noted on the next day, “Buried 200 rebs, they lay pretty thick.” On September 17, he was till at the grim work, “bury 250 today.” Remarkably, the burial details at Fox’s Gap were still at it as late as September 18. As Deady noted: “Same old work awful smell to work by. To day finish and glad of it.” On the same day, Private John McNutty Clugston of the 23rd Ohio noted, “Finished the burying of the dead at 4 P.M. and proceeded to Boonsboro and camped in a barn.”

The burial details at Fox’s Gap spent three days, apparently on their own with little supervision, burying more than 450 dead Confederates. Many of the soldiers were using alcohol to numb their senses. These unfortunate Union soldiers rejoined their regiments at Antietam just as the burial details of that momentous battle began the grisly task of burying the dead in the fields around Sharpsburg.

58 Bodies

As far as the well is concerned, the intoxicated men may have simply viewed the well as a convenient receptacle. Or, it may have started by someone dumping amputated limbs into the well on September 15, and then naturally continuing with whole bodies the next day. For the burial details it would have seemed that the well was already ruined and therefore it was only natural to continue. This brings up another aspect of the legend, that the well was not ruined because it was abandoned and dry. Once again there is evidence in the family history that indeed the well was dry, not because it was abandoned, but because as Anne Cecilia (Daniel’s granddaughter) remembered, it was under construction at the time.

Whatever the spark of origin, or condition of the well at the time, at least 58 dead bodies ended up in Wise’s Well on September 16. Samuel Compton’s account was verified in both a remarkable and roundabout manner by someone else associated with the 12th Ohio Infantry. Eliza Otis, the wife of 2nd Lt. Harrison G. Otis. Eliza noted the incident in her journal. It was occasioned by the visit in June 1863 of some fellow officers that served with her husband. In the course of the evening’s conversation, some incidents and “personal observations” of previous battles were discussed:

“In one place, near South Mountain, I think, they said it was, sixty dead bodies were thrown into a deep old well– that was their only sepulcher– they were those of the rebel soldiers, and were placed there by our men who were three days in burying the dead, and time and their various duties gave them no opportunity to afford the fallen foe a better mausoleum.”

It is appropriate at this juncture to clarify that Captain Charles F. Walcott, whose account of the incident became the basis in popular Civil War history, was not there when the incident happened, because he marched off the mountain with his regiment on September 15. Walcott received his information second-hand, and footnoted his account by saying that the story as he described it was told originally to a member of the Sanitary Commission by Daniel Wise:

“This account of the burial of the rebels was given by Mr. Wise himself, a few weeks after the act. to a gentleman connected with the Sanitary Commission, who noticed that the well had been filled up, and asked him how a man’s hand came to be projecting through the sunken earth, with which it had been covered.”

The Sanitary Commission was a civilian organization whose basic object was to better the living conditions of the Union Army. Walcott did not name the source, only that it was a “gentleman” connected with the commission, but his anonymous second-hand account in his 1882 regimental history has been accepted over others written by those who observed first-hand what actually transpired at Wise’s farm.

It must have been a very frustrating couple of days for the Wise family. Not only were they unable to immediately get back into their home because it was being used as a field hospital, but they most likely had to wait several more days until the burial details had finished their work. According to the Wise family history, “there were bodies in the well when they came back.”

Bowie’s List

Sometime around 1869, Moses Poffenberger and Aaron Good were employed by the state of Maryland to inventory Confederate burial places and visited Fox’s Gap. Although most of the Union soldiers who perished in Maryland had already been re-interred at the Antietam National Cemetery by then, the Confederates mostly remained buried on the battlefields. Both Poffenberger and Good visited, identified, and cataloged every trench and grave they could find. Under the auspices of Governor Oden Bowie, their list was published with the title: A Descriptive List of the Burial Places of the Remains of Confederate Soldiers, Who Fell in the Battles of Antietam, South Mountain, Monocacy, and other Points in Washington and Frederick Counties in the State of Maryland. Today it is simply known as “Bowie’s List.”

Poffenberger and Good listed 47 unknown “In Wise’s lot on east side of house and lot on top of South Mountain.” They also listed 23 unknown “In Wise’s lot on west side of house and stable on top of South Mountain.” On page 51 of Bowie’s List is the succinct entry, “58 unknown, In Wise’s Well on South Mountain.”

In 1874, 12 years after the Battle of South Mountain, the Confederate dead were finally removed and re-interred at the Washington Confederate Cemetery in Hagerstown, Md. Incredibly, for 12 years the Wise family lived with the graves of 128 unknown Confederate soldiers in the immediate vicinity of their home. The work of removing the Confederate dead was contracted to Mr. Henry C. Mumma of Sharpsburg. He was paid $1.65 “per head.” As noted in the local Hagerstown Mail, June 26, 1874:

“Mumma has been most successful in his work and is at this time continuing its prosecution with vigor…Some of these bodies we have heretofore noticed as having been taken from the historical well on South Mountain battle-field, where they were thrown by Gen. Reno’s command.”

General Burnside’s 9th Corps was commanded by Maj. Gen. Jesse Lee Reno, who was mortally wounded at the close of battle and perished within hours. What is germane to debunking the accepted narrative of the well is to note that the Hagerstown newspaper attributed the act to “Reno’s command,” not Daniel Wise.

In 1876, six years before the publication of Walcott’s regimental history, Daniel Wise died. He never knew of the legend that grew from Walcott’s storytelling, published in 1882. John Wise sold the property in 1878, two years after his father’s death, and moved to West Virginia. When Walcott’s book was published, the Wise family had left Fox’s Gap.

Excavation and Discovery

In the early 2000s, the National Park Service purchased the site of Wise’s well for incorporation into the Appalachian Trail. During the summer of 2002, a collaboration of archaeologists, historians, and trail volunteers explored the site and accomplished some meaningful archeology for the first time. They discovered a rectangular brick and mortar shaft feature in the vicinity of the suspected cabin site. A visual examination of the interior revealed a half dome-shaped concrete vault structure under the shaft. It was interpreted to be the top of a concrete cistern, that is, an underground tank for holding water. This was consistent with conversations of former residents who insisted there was no well, but a cistern instead, perhaps constructed by later residents as an alternate water source.

That theory, however, was debunked. Upon further excavation the bell-shaped concrete vault was found to be sitting on at least four courses of dry laid stone that undoubtedly surrounded an open shaft that was consistent with a hand-dug stone-lined 19th-century well or cistern. The feature was filled with debris, most of which looked to be from the mid- to late-20th century. No other stone-line underground structure that could have been used as a well or cistern was found near the cabin site that summer. Although not entirely conclusive, it does appear that the archaeologists found Wise’s famous historical well. It also appears that it was later used for a time as a functioning cistern.

Setting the historical record straight is often condemned as “revisionism.” The story of Daniel Wise’s well has become cemented as fact in the history of the Maryland Campaign and, unfortunately, much of it is legend. The campaign has more than ample drama and human interest that is well documented and so its history should not include incidents that have no basis in the historical record.

To “revise,” by definition, implies correction and improvement. I have attempted to correct the Wise’s well story; not demolish it. The intent has always been to exonerate Daniel Wise from blame for an onerous act he never committed. Without doubt the well became a mass grave for at least 58 dead Confederate soldiers. What I have done is merely correct the narrative behind how they got there and, in the process, expose some of the true horror of warfare.

The 58 unfortunate Southerners were not put in the well on September 15, but rather the next day, September 16. Daniel Wise did not put them there, a drunken Union burial detail did; and there is no evidence that Wise, or any member of his family, got $1 per body, or any compensation for damages done.

Steven R. Stotelmyer writes from Hagerstown, Md., and is the author of The Bivouacs of the Dead: The Story of Those Who Died at Antietam and South Mountain and Too Useful To Sacrifice, Reconsidering George B. McClellan’s Generalship in the Maryland Campaign. He is a National Park Service Volunteer as well as a Certified Antietam Battlefield and South Mountain Tour Guide.