As I race down Rohrersville Road near Boonsboro, Md., the magnificent South Mountain range to the left and a sign advertising a local moonshine tasting to the right, three thoughts linger:

Will that duct tape hold up on the crumpled left, rear panel of my car? (Curses to you, Cross Keys battlefield cows and bull that made me back into a fence post!)

Can I make that tasting before lunch? (Sadly, no.)

What would Mrs. Banks say if I suggest a move from our home in Nashville to this gorgeous area? (You don’t want to know.)

“There are few places that I have visited or of which I have ever dreamed that have such a hold upon my heart as the picturesque hills and broad valleys of Western Maryland,” battlefield tramper and historian Fred Cross wrote about this area in 1926. This land entrances me, too.

My destination is the east side of South Mountain and the “It’s-OK-to-leave-your-car-and-house unlocked” village of Burkittsville, population roughly 200 if you count the dogs and cats. You may remember it as the setting for that weird 1999 horror film, The Blair Witch Project.

At the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862, three days before the much-bloodier Battle of Antietam nearby, cannon boomed and gunfire crackled from Crampton’s Gap as desperate Army of Northern Virginia soldiers were routed by Maj. Gen. William Franklin’s 6th Corps. Afterward, Burkittsville was overwhelmed with wounded and dead.

With heroes, too.

Seventy-five-year-old Paul Gilligan hustles to tidy up a circa-1850 house he owns before visitors check in to the Airbnb on Burkittsville’s main drag. (The wartime owner was a physician who cared for soldiers after the battle.) But the no-B.S. Irishman, president of the Burkittsville Preservation Association, takes time out to discuss with me a preservation effort he champions in this Civil War time capsule 60 miles northwest of Washington, D.C.

A retired public health service officer, Gilligan lives in a late–18th century stone farmhouse in Burkittsville astride Gapland Road. On the afternoon of the battle, Federal soldiers, their hearts racing, advanced over Gilligan’s property on the way up the steep slopes toward Crampton’s Gap. In 2019, state archaeologists unearthed 600 battle artifacts on his farm. A year earlier, a relic hunter uncovered a sabot from a Blakely shell fired from the gap by a Confederate battery.

At the corner of West Main and Burkittsville Road, Gilligan runs PJ Gilligan Dry Goods & Mercantile Co., a general store, from an early–19th century building with a faded yellow façade. Across the road stands the gleaming-white, Greek Revival-style German Reformed Church, U.S. Army Hospital D following the battle. Blood of soldiers once spattered its walls, gruesome evidence of dozens of amputations. Next door stands the red-brick St. Paul’s Lutheran, also a wartime hospital. In all, roughly 60 of the town’s 70 houses date to at least the 19th century.

“A freaking museum,” Gilligan calls Burkittsville, where he and his wife, Laurel, settled in 1985.

One of the places he and the Burkittsville Preservation Association aim to save is the Martin Shafer farmhouse and outbuildings, Franklin’s Crampton’s Gap headquarters a mile from Gilligan’s store. Gilligan has a serendipitous connection to the five-acre farmstead, transferred to the association in 2016 (for a tax write-off) by the nephew of its last owner, Mary Shafer Motherway. Decades ago, Gilligan and his father drove past the farmhouse. “I know him,” said Dad, pointing to the mailbox outside. Mary’s husband, Tom, lived in the same duplex where the elder Gilligan grew up in Somerville, Mass.

Deftly maneuvering through bureaucratic channels, Gilligan secured a state grant to help preserve the farmhouse. His dream is to house a museum and visitors’ center in the circa-1820 dwelling—a place to interpret the Battle of South Mountain and for the hundreds of relics from his farm to be displayed. But money from the state won’t nearly cover the preservation work required.

Eager to visit the Shafer place, I excuse myself. Gilligan doesn’t mind: “I gotta clean the jawnzzz,” says the Massachusetts native.

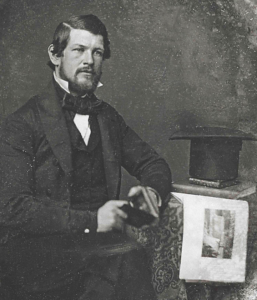

One hundred and fifty-nine years ago, 39-year-old William Franklin, a career soldier and expert engineer, enjoyed a meal and smoked cigars in Martin Shafer’s yard with fellow generals Baldy Smith, Winfield Scott Hancock, and Henry Slocum, among other 6th Corps brass. Encamped near Shafer’s house were thousands of U.S. Army soldiers—including 3rd New Jersey Private Charles Hamilton Bacon, a 32-year-old father of five, and 32nd New York Colonel Roderick Matheson, a 38-year-old Scotsman who got gold fever in 1849 and sailed around Cape Horn for California. A teacher as a civilian, Matheson volunteered soon after the war began.

“Netty, my love, what would I do or give if you were by my side, that I could look into your face and get your approving smile for trying to fight and sustain YOUR country and now mine,” Matheson wrote to his wife in the summer of 1861. “Do you not think I may, by and by, rank as an American?”

This afternoon, the only human I spot near the corner of Gapland and Catholic Church roads is a man hunting for war relics in the field across the way. So, I deploy a one-man skirmish line and surprise Ron Brown, who slightly darkens this sun-splashed day when I discover he’s a New England Patriots fan. The 47-year-old physical security supervisor from nearby Jefferson, Md., has hunted the area for Civil War artifacts since COVID struck. The day before, as a volunteer at the Shafer farmhouse, Brown used his Garrett Ace 400 metal detector inside the home’s billiards room, a postwar addition. “Found a bunch of nails, a padlock, and some hand tools,” he says.

In his nearly 2½-hour relic hunt this day, Brown has unearthed one bullet, near Crampton’s Gap, and a chunk of postwar iron. But in other area hunts, he has recovered “Georgia rounds,” pieces of a Federal spur, and Union breast plates. The finds are meaningful for Brown, who has an ancestor who served with the 14th New Hampshire in the Army of the Potomac (Ezekiel Hadley) and another with the 31st Illinois (Thomas Jolly). Confederates inspired Jolly, a merchant as a civilian, to enlist when they confiscated his goods in the South—“it pissed him off,” Brown says. Though shot in the head during the Battle of Atlanta, he survived the war.

At the Shafer House, the entire west-facing wall has been carefully removed, exposing a hanging chandelier and a bleak interior. Workers eventually will cover beams and joists with cement cinder blocks as well as bricks salvaged from the house.

During a 2017 visit inside, I examined damage done by vandals, time, and nature. Perhaps a target of thieves, an old fireplace mantle was loosened from its moorings. Cracks snaked through interior walls. Covered with dust, a brown bottle of DDT, the long-banned insecticide, stood on a shelf. In the attic, Roman numerals were etched into wooden beams, a common construction practice long ago. In a downstairs room, perhaps the very one where Franklin met with Union commanders in 1862, four old ironing boards rested against a wall.

Outside, I examine the rickety, Pennsylvania-style bank barn, recently a victim of a windstorm. That structure, as well as the ancient, stone meat house and well house/machine shop, needs significant repairs. In the front yard, across from the field where 6th Corps soldiers camped, a homemade sign pleads for volunteers on workdays to help save the property:

“Your 2+ Hours.” it reads. “Big Help.”

So, why is Gilligan so eager to preserve this special town? “History,” he tells me, “sells.” The stories that still linger here under the preservation bubble, like puffs of smoke from a musket barrel, captivate him, too. More than 100 U.S. Army soldiers sacrificed it all at Crampton’s Gap to save the Union.

Charles Hamilton Bacon was one of them.

Late on the afternoon of September 14, as the 1st New Jersey Brigade swept across Mountain Church Road or fought at Crampton’s Gap, the private was fatally wounded. “He went into the fight with unusual vigor, his health having greatly improved recently, faltering not until a ball passing through his Testament, which he always carried with him, entered his abdomen and caused his immediate death,” regimental chaplain George Darrow wrote to Bacon’s wife, Ann.

A “consistent Christian,” Bacon was buried with eight of his comrades under an elm on Jacob Goodman’s farm, ground astride Mountain Church Road. Perhaps the burial was on the very land preserved by the American Battlefield Trust. Bacon’s final resting place is unknown.

After suffering a bullet wound in the right thigh in the same attack, Matheson was evacuated to a field hospital in Burkittsville. The injury was not deemed serious, but he died on October 2 after blood poured from the wound. The U.S. Army lamented the loss of a man Franklin called “one of its best colonels.” After his death, Matheson’s remains took a circuitous route home to California.

On October 9, his body lay in state at City Hall in New York. Then a military funeral was held at the Green Street Methodist Church, where he and Netty were married in 1848. Nearly a month later, Matheson’s remains arrived by steamer in San Francisco. On November 9, 1862, the Scotsman was buried at Oak Mound Cemetery in Healdsburg.

Days later, a California newspaper solicited contributions to pay the $5,000 mortgage on Matheson’s Sonoma County farm, which faced imminent foreclosure. Netty and the couple’s children—Roderick Jr., 13; Nina, 7; and a baby named George—lived there.

“[The donations] need not be large,” wrote The Sonoma County Journal, “but they ought to be universal, so that everyone who believes that Colonel Matheson has sacrificed his life in a holy cause may have the privilege of aiding to give independence and comfort to his family.”

A fitting tribute, indeed, to a hero of Burkittsville.

John Banks lives in Nashville, Tenn. He thanks the Healdsburg (Calif.) Museum for the use of the Matheson correspondence.