In January 1918, as U.S. participation in World War I neared its first anniversary, historian James G. Randall of the University of Illinois wrote perhaps the definitive article on Northern newspapers and military secrecy during the Civil War. Randall’s magisterial account, appearing in The American Historical Review, served a dual purpose. He intended it both as an overview of a dilemma Union armies faced during the Civil War and as a gentle reminder to U.S. newspapers that might feel emboldened to follow suit in similar scenarios in World War I. “The American Civil War presents a significant field for study in this connection,” Randall wrote, “for the double reason that a period of remarkably keen journalistic enterprise coincided with a time of laxity in the matter of press control. Acting under no effective government restraint, the newspapers of the North, though in many ways deserving of admiration, undoubtedly did the national cause serious injury by continually revealing military information.”

As Randall showed, occasions when Northern newspapers were all too ready to publish sensitive military information to an eager public—and to ever-vigilant enemy spies and commanders—were plentiful.

The process of how military intelligence has been gathered and implemented has evolved gradually since the Civil War, and continues to evolve today. Modern U.S. Army doctrine breaks the process down into four general categories: Role; Target; Intent; and Functions. Below, by examining Union Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s 1862 North Carolina Expedition, we expand on Randall’s 1918 thesis through the lens of this modern Army doctrine.

Inside Information

In the fall of 1861, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, the Union Army’s general in chief, endorsed creating a “coastal division” for operations against Confederate coastline targets. “Little Mac” tapped Burnside, an old friend, to organize and lead the expedition.

Burnside formed mostly newly raised regiments, many specially recruited in New England coastal communities where most would have some experience with boats. He organized his force into a three-brigade division of about 15,000 men, concentrated at Annapolis, Md. In early January 1862, this force, transported by a large armada, left Annapolis and attacked the North Carolina sounds. It achieved some success, against badly outnumbered and ill-equipped Southern opposition.

Confederate military leaders were known to regularly scan Northern newspapers for information. In late 1861, the lines along the Potomac River were ill-guarded, and Confederate pickets could be found within 20 miles of Washington, D.C. That, along with an abundant number of Confederate sympathizers in the capital and Maryland, usually allowed next-day access to these newspapers.

General Robert E. Lee, Randall noted, “constantly perused the columns of these journals with the eye of a military expert on the lookout for information.” Lee would then pass the newspapers on to President Jefferson Davis, with comments on items he believed were of special interest. Randall cited four specific instances when Lee had made moves in response to what he had discovered in these papers.

After the First Battle of Bull Run, acerbic Union Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman, complained that “the press…gave notice of [our] movement on Manassas, and enabled [Joseph] Johnston’s army so to reinforce [P.G.T.] Beauregard that our army was defeated.”

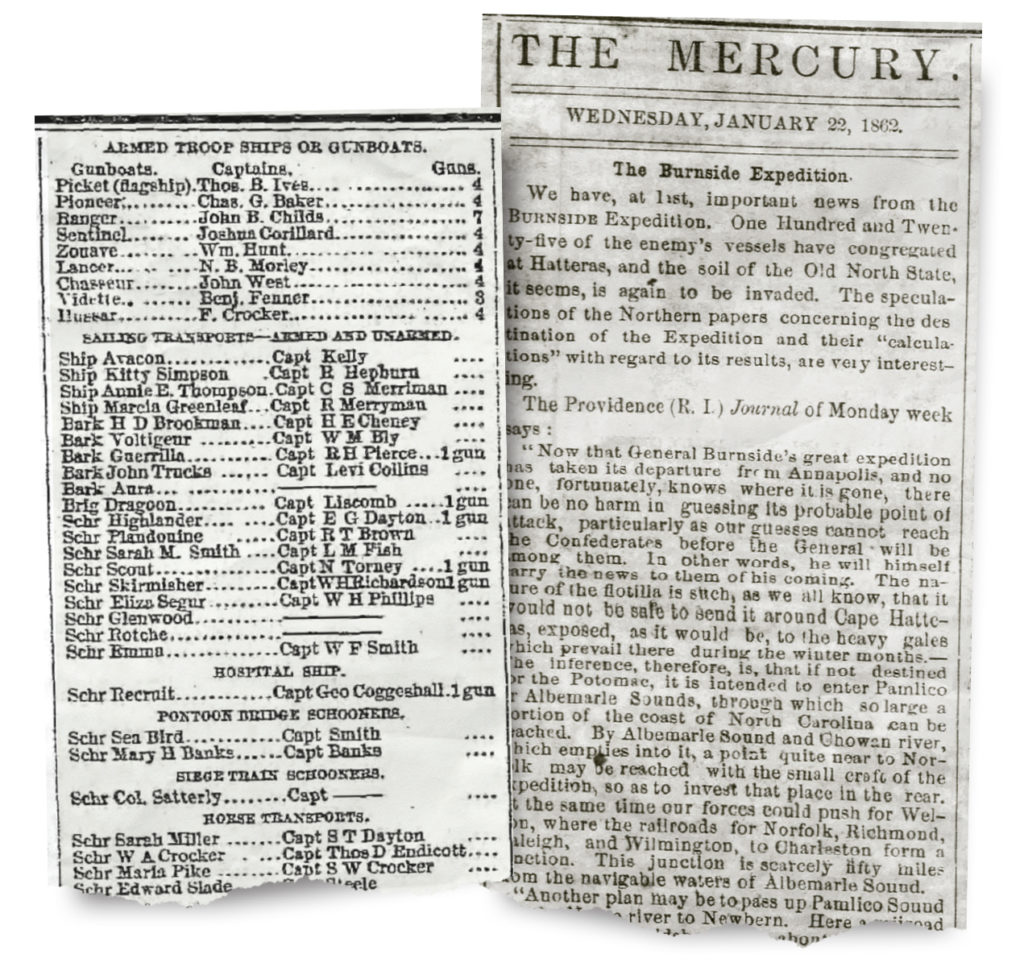

The Official Records of the War provide evidence that Confederate intelligence operatives regularly received information on Burnside from Northern newspapers. For example, on January 4, 1862, Confederate Colonel Thomas Jordan forwarded the following extract from the December 28, 1861, National Intelligencer to the War Department in Richmond.

“General Burnside is awaiting the arrival of gunboats and transports at Annapolis. Sixteen transports, four schooners, and five floating batteries are already there. The naval rendezvous will be at Old Point Comfort [Fort Monroe], and it is said that Captain Goldsborough is assigned to the command.”

From an intelligence standpoint, it is in the categories of capabilities and order of battle that Northern newspapers did the most damage. On September 28, 1861, with the expedition still in the planning stages, the national magazine Harper’s Weekly proclaimed that Burnside would lead “at least 10,000 men” in a move to flank the rebel armies in northern Virginia, and “to take Norfolk in the rear.” That was a remarkably accurate estimate of the force eventually used, that it would be commanded by Burnside, and that Norfolk was the likely target, as the Confederate port stronghold could be taken only from North Carolina’s Pamlico and Albemarle sounds, via canals connecting those sounds to Norfolk.

Such disclosure of Burnside’s numbers was critical. As has been well-documented, McClellan tended to let his operational choices in 1862 be influenced by a gross overestimate of Confederate army numbers. The flip side is that an accurate knowledge of Burnside’s numbers and capabilities better enabled the Confederates to conjecture on Burnside’s destination.

Worse would come soon. On October 7, The Providence Evening Press reported that Burnside “expects to have ten regiments [about 10,000 men] under his command,” and named several of the regiments. This information made it south, as The Savannah Morning News soon echoed that report of Burnside’s numbers and projected he was aiming for the Chesapeake Bay. (That isn’t to say the information provided in those early days couldn’t be sketchy. There were inaccurate newspaper reports that Brig. Gens. Isaac Stevens and Thomas W. Sherman would have commands in the expedition.)

On October 23, Burnside was ordered to concentrate his division at Annapolis. It took less than a week for this rendezvous location to leak out, with The New York Herald of October 30 conveniently informing the world that the 51st New York Infantry was not only part of the expedition but also had been ordered to Annapolis. Newspapers kept up a steady stream of reports detailing the exact regiments, and their commanders, ordered to join Burnside.

The actual destination of the expedition, however, had not been settled yet. Newspaper accounts speculated on three likely targets, the same three targets that any competent Confederate officer would have assumed: the Chesapeake Bay area, in conjunction with a move by McClellan’s main army; the North Carolina sounds; or the Charleston–Savannah region, reinforcing Union troops already at Port Royal, S.C. Here Burnside committed an error. On November 7, while in New York City securing vessels, he addressed a gathering of exiled North Carolina Unionists. It was unnecessary for a serving general to address a civilian gathering, and Burnside’s interest in North Carolina was widely reported. Fortunately perhaps, other early November newspapers speculated his target would be Port Royal.

Early Confederate intelligence was divided on the potential point of attack. As early as October 1861, spies connected to Rose Greenhow’s Washington-based ring reported the target to be North Carolina, but as late as January 4, 1862, Jefferson Davis had received information that the Potomac River was Burnside’s target, in connection with an advance by McClellan’s army.

In a true gift to the Confederacy, The New York Herald (which seems to have been the worst of the Northern newspapers when it came to leaking secrets) ran a lengthy article in early November giving the names of all the regiments and their commanders then at Annapolis, plus their strengths, their armament (mostly Enfield rifles), and even details of the baggage train that had been gathered. From this information on numbers and capabilities, the Confederates could easily discern that the expedition was not equipped for large-scale operations outside coastal areas.

On November 19, one Washington newspaper listed the 15 regiments and their commanders that made up Burnside’s division. On the 28th, the Herald printed a complete breakdown of Burnside’s troops, with biographies of the officers, the names of the transport vessels, even details of their pontoon train. The next day The Philadelphia Press also listed the regiments, the names of the generals and colonels, and the names of the staff officers and vessels. We know from The Official Records that these lists of units and vessels were remarkably precise. Every newspaper report of the expedition gave fairly accurate information about its strength and order of battle, although at this time reports varied on the destination and timing of the expedition. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper admitted the expedition’s destination to be unknown, but “it may be Mobile, New Orleans or Galveston”—all in the Gulf of Mexico. Both The New York Tribune and The Chicago Tribune considered the York River (Chesapeake Bay) the likely target, working in conjunction with McClellan’s main army.

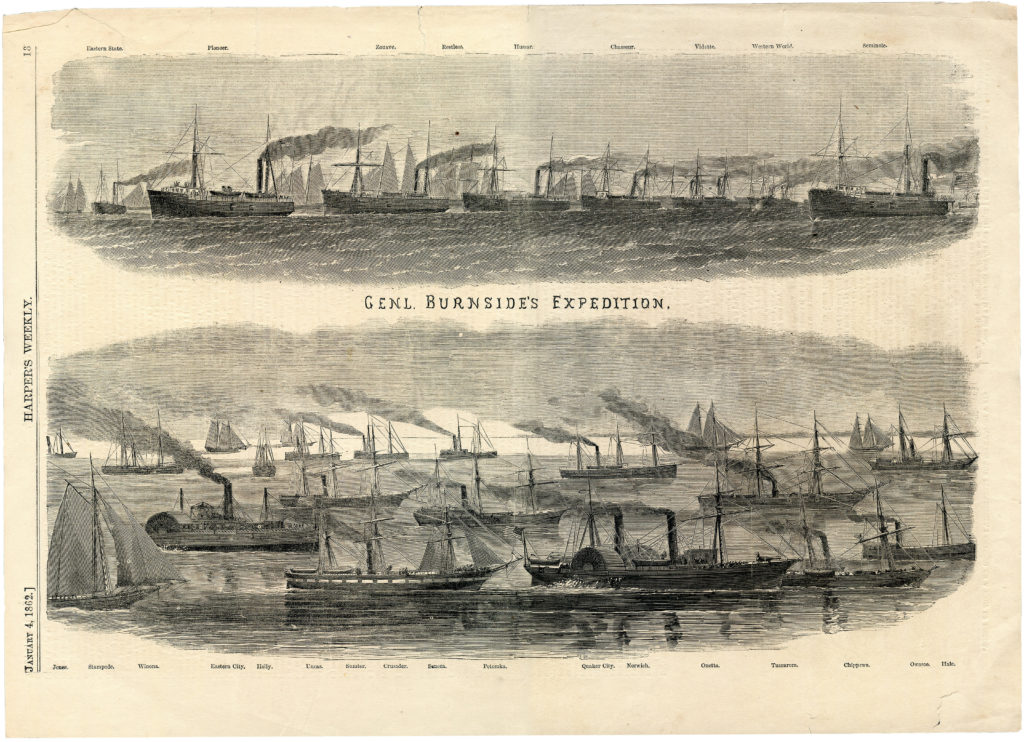

Perhaps the worst leak—certainly the most visual—came from Harper’s Weekly. Its January 4, 1862, issue featured a full page of illustrations of “Genl. Burnside’s Expedition,” depicting the fleet, with the names of the vessels given. Harper’s admitted that the destination “is, of course, secret” but surmised that it would operate from a base not far from Fort Monroe (i.e., either the Chesapeake Bay or North Carolina). Just from the list of vessels, and their known tonnage, the Confederates could estimate both the numbers of troops the ships could transport and the amount of supplies carried, which would serve to narrow the list of possible targets.

In case the Confederates did not have Harper’s handy, on the same day The Washington Evening Star provided similar information, adding that the vessels were almost fully loaded and ready to depart. This newspaper identified the caliber of the cannon on each ship, the ship’s draught and size, and told the world that the Annapolis boats would meet up with other naval warships already at Fort Monroe. Confirming the Fort Monroe speculation, The Lowell (Mass.) Daily Citizen of January 9 printed a letter from a captain of the 25th Massachusetts Infantry saying he had been ordered to prepare only three days’ rations, indicating a long cruise (i.e., to Port Royal or the Gulf) was not contemplated.

In fact, on January 2, 1862, Burnside had met with McClellan and final orders were issued for the expedition to depart as soon as possible, for the North Carolina sounds. The transports left Annapolis on January 9-10, rendezvoused with other vessels at Fort Monroe on the night of the 10th, and finally departed for Hatteras Inlet (the entrance to the North Carolina sounds) on January 11. Northern newspapers promptly reported all these moves. The Port Tobacco (Md.) Times of January 9, followed by The Philadelphia Press and The Baltimore American, announced Burnside’s departure. On January 11, The Washington Evening Star noted that while the troop vessels had sailed by the 10th, vessels loaded with “stores, etc.” would not depart for two or three more days.

The fleet’s arrival at Fort Monroe could be seen from nearby Confederate-held Norfolk. As early as January 9, newspaper reports circulated that Burnside’s advance vessels had reached that bastion. The Newark (N.J.) Journal reported on January 13 that Burnside and his staff arrived at the fort on the 11th, while The Providence Journal and Washington Evening Star assured readers that Burnside was heading toward Pamlico Sound.

Burnside’s Involvement

Burnside seems to have been aware of these newspaper leaks, although (as can be seen) his efforts to stop them failed. On January 10, The New York Tribune blandly and incorrectly asserted that “the secret of [Burnside’s] destination and field of operation has been well kept.” The Boston Morning Journal of the 13th even claimed that “General Burnside is determined that no indiscreet correspondent shall make public any details concerning his expedition, or its destination, until it is safe to do so” and claimed that Burnside had quarantined reporters on one of his ships to prevent word leaking out. Given the tsunami of leaks to the press, one wonders if these newspapers took what they wrote seriously, or whether they were trying to “butter up” the general in order to get more “scoops.”

Burnside himself became a chief offender. On January 14, The Cincinnati Daily Commercial gave out all the details of the expedition. The report was datelined the 5th, but not released until nine days later, as Burnside had asked the reporters not to release it until he deemed it “safe” to do so. This report (accurately) named the North Carolina coast, and Roanoke Island, as the first targets. It cited a force of 16,000 men and 53 cannons, astonishing (and accurate) detail that a Mata Hari would have been proud to have discovered.

The vessels were said to contain only eight days’ worth of coal and 10 days of food, confirming a short voyage (i.e., North Carolina). And with the troop-laden vessels still at sea, several Northern newspapers (from The Washington Evening Star to The Cleveland Daily Dispatch) printed these facts, and specified the Tar Heel State as the target. As the voyage to North Carolina, which normally was a matter of a few days, could take—and, in fact, did take—weeks to complete due to gale-force winds, Burnside’s notion of when it was “safe” to unleash the newspapers seems wildly optimistic, almost criminal—certainly a violation of any notion of secrecy.

The Philadelphia Inquirer of January 18 published a report in such detail that it could have come only from a member of Burnside’s staff. After listing the brigades and regiments in each brigade, with their commanders (accurately in each case), it furnished a list of all the company officers of every regiment, down to the 2nd lieutenants, and on which vessels each regiment had embarked. Details of the pontoon train, the cost and composition of the artillery ammunition, names of even the junior signal officers, and more, were disclosed. The article claimed that “Gen. Burnside has afforded the press every facility for obtaining” these priceless details, which casts serious doubts on Burnside’s later claims that he clamped down on security.

Lest anyone on either side was still in doubt as to Burnside’s target, The New York Sun of January 24 printed a long article on the expedition complete with a map of the North Carolina sounds. The New York Herald on the 28th printed another map of the region and filed a long report on ships that Burnside had lost in the storms, together with the names of the units on board the lost ships. The names of the five ships lost, with their cargoes, match up with the actual losses. In addition, the reports on the storm and the difficulties the ships had in getting over the shallow inlet waters, explained to the world the reasons for the delay in the attack. This almost-real-time update would be the last actionable newspaper leak prior to the attack.

It took until February 5 for the entire fleet, buffeted by gales that almost sank Burnside’s headquarters vessel, to anchor off Roanoke Island and transfer to shallower draft vessels that could enter the sounds. The troops commenced their attack two days later. The newspaper reports thus gave the Confederate authorities nearly three full weeks’ notice of the intended site of attack. Southern newspapers even reported the impending attack, and urged the government to react, though there was still some doubt as to where in the sounds the first attack would be made.

Fortunately for Burnside, the Confederacy had few resources available to move to the threatened area. The Confederate high command denied requests by the local commanders to reinforce the area. Thus, despite knowing in advance this priceless information (all the information any army could reasonably ask for), the outnumbered and outgunned Confederate defenses in the area collapsed.

Lessons Learned

Why were army officers and reporters so cavalier about military security early in the war? For reporters, the answer seems obvious: the leaks were “news” and sold newspapers. After all, the information was from army sources, and why would reporters hold themselves to a higher standard of security than the army itself? There was neither an American newspaper tradition of keeping secrets, nor a law that made it illegal to report those secrets. Army officers such as General Burnside had less excuse for the lax security. It must be remembered that most army officers had been, six months before, civilians, who at a minimum had no background regarding military security. Many officers were prewar politicians who had spent their lives seeking newspaper publicity. Regular Army officers like Burnside, however, should have known better.

A look at the Mexican War, in which the U.S. Army paid little attention to newspaper security, is instructive. As that war was fought in Mexico, the Army had much greater control over such reporting. But by 1861, the information infrastructure of telegraphs and railroads had developed to the point where news could be transmitted in mere days, if not hours. Civil War army officers’ Mexican War experience little prepared them for dealing with that sea change.

For at least the first year of the Civil War, the Confederacy didn’t need an organized intelligence-gathering service in the North—at least, one along the lines of modern military intelligence. Northern newspapers did that job for free. Burnside shared a lot of the blame for openly cooperating with the newspapers.

Modern military intelligence services would gladly pay tens of millions of dollars to obtain the kind of information on numbers and intentions that Northern newspapers provided the Confederacy. The newspaper information on Union numbers, order of battle, and capability was nearly always accurate, and eventually even Union intentions were disclosed. The famous spies of history, from Mata Hari to the Rosenbergs, lost their lives to obtain a mere fraction of the military intelligence that the South received virtually risk-free.

Fortunately for the Union, security tightened up as the war progressed. An analysis of newspaper reporting of a similar troop movement in 1863—the transfer of the 11th and 12th Corps from Virginia to Chattanooga—proves that newspaper mentions were few and scattered, with none giving the kind of troop-strength details seen in late 1861–early 1862. By no coincidence, the more the Union Army kept its secrets out of the newspapers, the better it performed.